[Photo story] Puyi: The last emperor of China

The tragic life of the last emperor of China has been the subject of much popular culture, not least the movie The Last Emperor. But why was he often thought of as a political puppet and how did he go from emperor to commoner? Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao provides a glimpse into the final period of China's imperial rule.

(Images courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

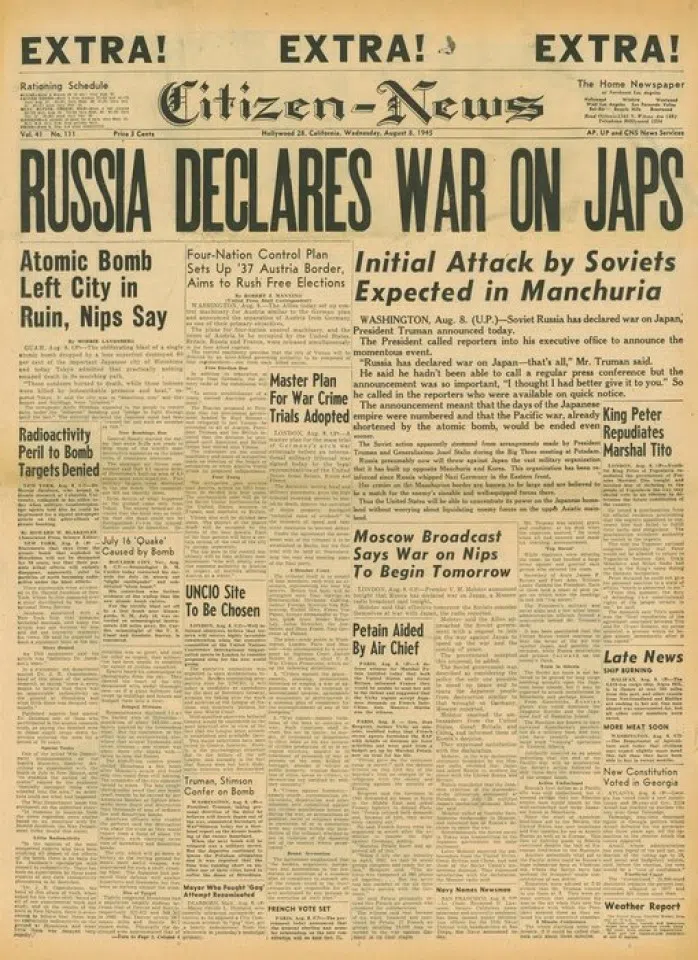

On 16 August 1945, the emperor of Manchukuo, Aisin Gioro Puyi, was with his family at the airport in Shenyang, about to escape to Japan on board a Japanese military aircraft, when he was detained by the Soviet Red Army and sent to be incarcerated in the Soviet Union as a WWII Allied prisoner of war.

After thousands of years of the imperial system, Puyi was the very last emperor of China. His difficult life was a symbol of China's fate and the enormous changes happening in the world.

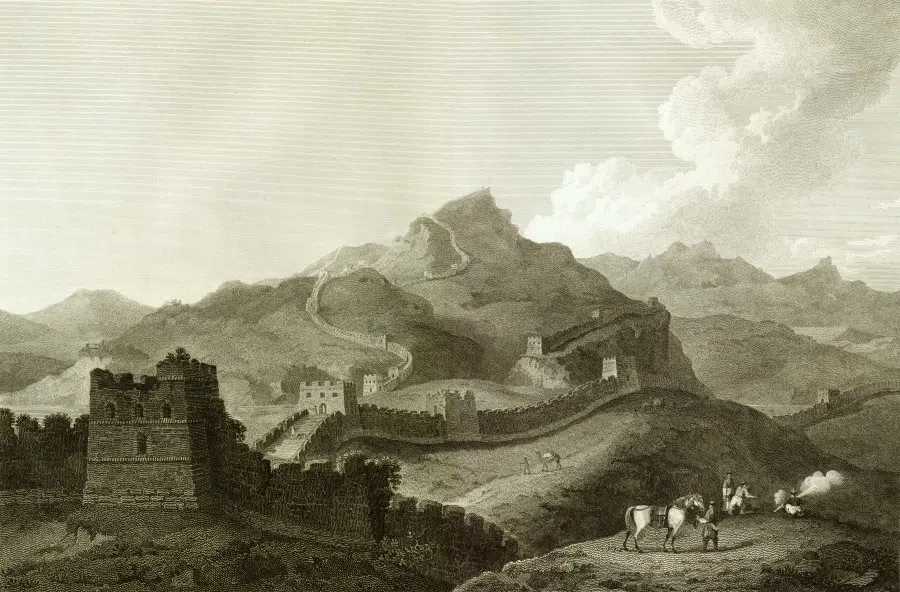

The Qing dynasty was the last of China's dynasties. It was established by the minority Manchurians, a nomadic group from northeast China, and was one of China's most powerful dynasties. China's current territory is generally inherited from the Qing dynasty.

The history of the Manchurians is closely intertwined with that of China. Its people became powerful in the early 12th century and defeated the Song dynasty, occupied northeast China and established the Jin dynasty, which they saw as a legitimate dynasty of China. They gradually assimilated the Han ethnic culture, but a century later were driven back to the northeast by the Mongol empire. Subsequently, the Mongols were defeated by the Han-led Ming dynasty; 200 years later, the Ming dynasty grew weak and the Manchurians rose again, with outstanding political and military leaders, to establish the state of Qing. In 1644, the Qing army invaded China and occupied the whole of it within 40 years, including Taiwan.

China under the Qing dynasty

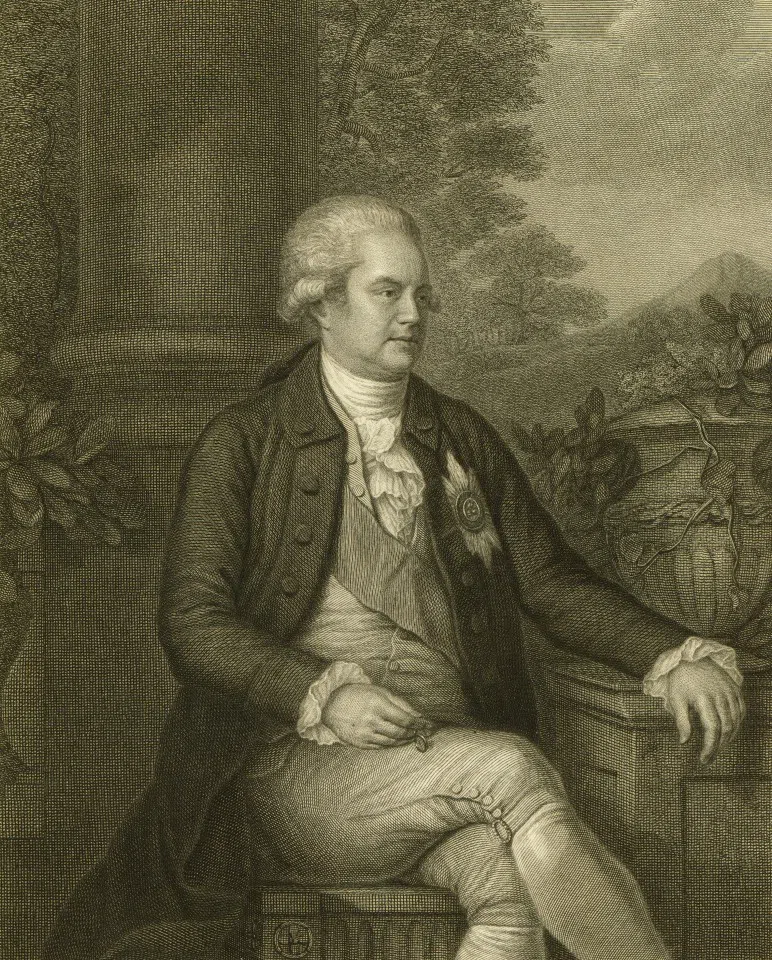

In 1792, Britain's King George III sent George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney as a special envoy leading a large delegation to China. He declined to kowtow when meeting the Emperor Qianlong according to the rules of the Chinese imperial court, sparking diplomatic friction. With rich text records and hand-drawn images by the British delegation on their return, Britain and the Western world had a deep impression of China and the Emperor Qianlong, who came to symbolise the power and authority of the Chinese emperors.

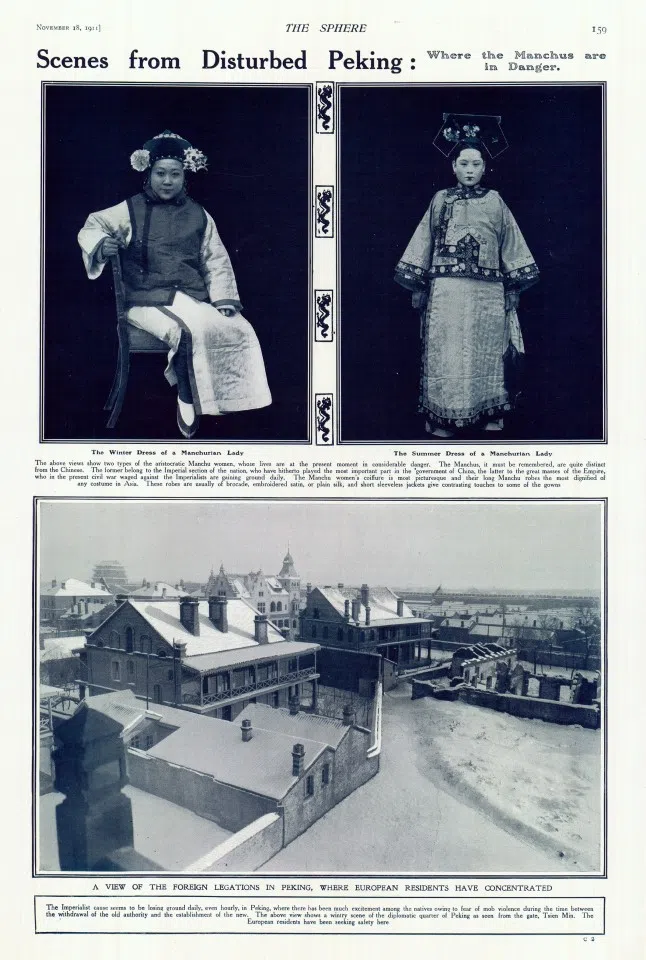

On the other hand, the Qing royal family were people from the grasslands, good travellers and strong fighters. Under the first three emperors, Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet became part of China, making it a huge, multi-ethnic empire. The Manchurians saw themselves as the legitimate successors of the Chinese dynasty. They forced the Hans to adopt Manchurian hairstyles and dressing, while they themselves switched to Han writing and language and customs, as well as institutions and systems. Nevertheless, the Manchurians were a minority group, having long-term conflicts with the majority Han population. Han resistance groups in southern China often put out calls to "oppose the Qing dynasty and restore the Ming".

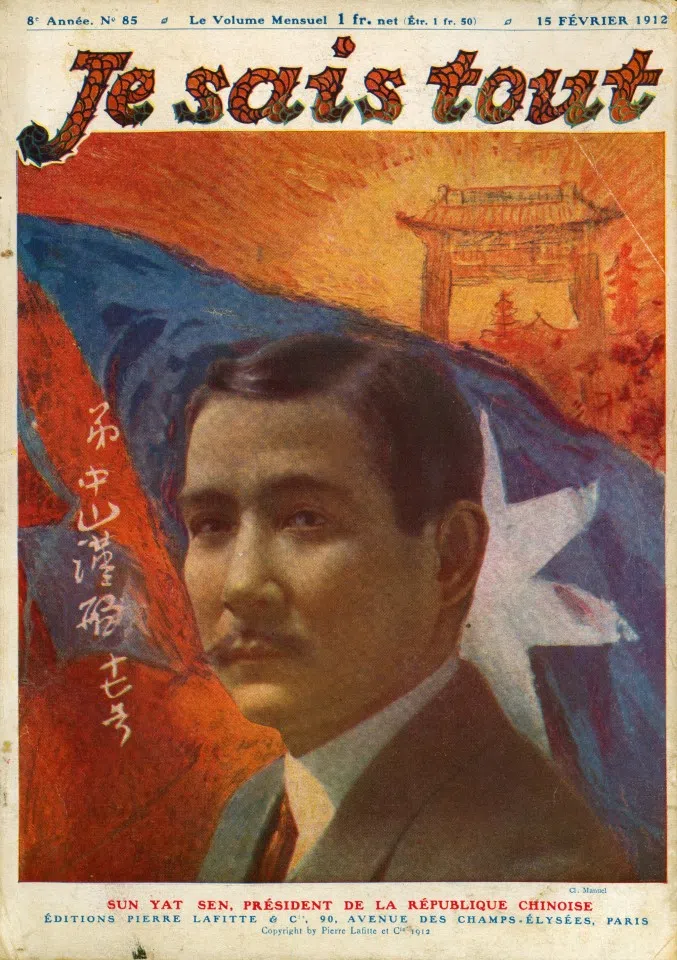

In the mid- to late 19th century, under bombardment from the guns and cannons on modern vessels owned by the rising Western maritime powers, the Chinese empire seemed as old and frail as many ancient empires. It was forced to keep ceding territory and pay reparations and was on the brink of crumbling, and was painfully humiliated. The Chinese Revolutionary Party led by Sun Yat-sen took the slogan "Expel the Tatars" - a call to drive out the Manchurians and restore Han rule. Many Manchurian officials became targets of attack and assassination, striking fear among them for a time.

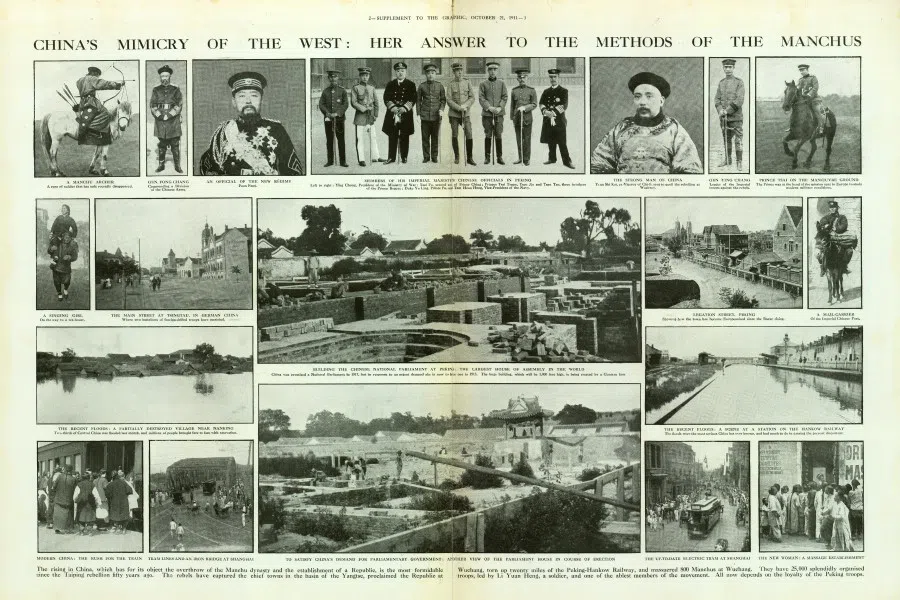

Days of revolution

In October 1911, the Chinese Revolutionary Party (CRP) started an uprising in Wuchang. While it was a sudden incident, the revolutionary army was a division that defected from the government's modern army. The revolutionaries possessed good equipment and training, and easily captured the three towns in Wuhan - Wuchang, Hanyang and Hankou. This was the first time that Sun Yat-sen's republican revolutionaries held major cities in the middle course of the Yangtze River, and inspired 17 provinces in southern China to join the uprising, declaring a breakaway from Qing dynasty rule.

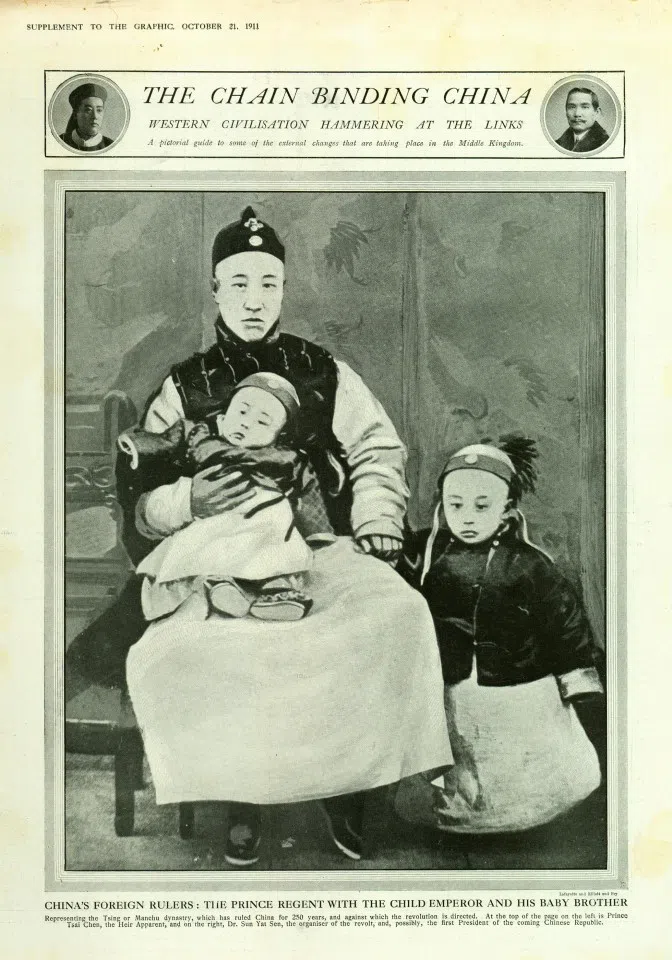

China's republican revolution shocked the world. At this time, the Manchu-majority Qing court was in disarray, and got Yuan Shikai - a Han general who had previously been forced out - to lead the modern army that he had trained to quell the rebellion in the south. After intense fighting, the Qing army seized back Hankou, and a deadlock ensued with the revolutionary army. Both sides then started negotiations.

Yuan Shikai was a wily official. During the negotiations, the CRP said as long as Yuan got the Qing royal family to step down, they could continue to live in the Forbidden City and enjoy royal treatment. Most importantly, they would support Yuan as the first president of the new Republic of China (ROC).

Yuan conveyed these terms to Empress Dowager Longyu, the mother of six-year-old Emperor Puyi, citing the tragedy of how French King Louis XVI and his family were mercilessly killed by revolutionaries. The frightened Longyu soon declared the royal family's abdication, ending thousands of years of imperial rule in China.

Uncertainty for the last emperor

Young Puyi naturally did not know what was happening. But outside the palace, the political danger was very real. Six years later, the October Revolution in Russia would wipe out Tsar Nicholas II and his entire family. No one knew whether the revolutionary flame of revenge would also take hold in China. Puyi's fate was uncertain.

Although after the successful revolution, Sun Yat-sen immediately soothed the ethnic conflict and defined China as a multi-ethnic country - a republic including Hans, Manchurians, Mongols, Huis and Tibetans - the first president of the ROC Yuan Shikai attempted to revive imperial rule.

After Yuan's death, China was thrown into years of chaos. While young Puyi was accorded the title and privileges of an emperor, the royal family remained in a dangerous situation. The opposition between the Manchurians and Hans was not resolved, while the republican government was not united or stable, with constant infighting.

In 1917, a group of queue-wearing conservatives even attacked Beijing, to help 12-year-old Puyi to reascend the throne. This short-lived coup was quickly snuffed out by the government, but it put the republican government on the alert. With imperial rule overturned less than ten years earlier, there remained many nobles, military officers and government officials of the previous dynasty within and outside of Beijing, and there was no lack of people who yearned for the return of the glorious imperial period.

As long as an emperor - even if in name - remained in the Forbidden City, that was a spiritual symbol of hope of restoration, and a threat to the republican government, which made removing this symbol a political necessity. In modern history, once a dynasty was forcibly overturned by republican elements, the ruling couple would generally be exiled overseas, because as long as they remained, they would be a threat to the republicans.

In 1924, Feng Yuxiang, a military leader of the republican government, initiated a coup in Beijing, driving Puyi and the royals out of the Forbidden City. And in 1928, a group of republicans sacked the Qing Imperial Mausoleum, destroying the bodies and stealing treasures - the leader was not prosecuted.

Humiliated and sidelined

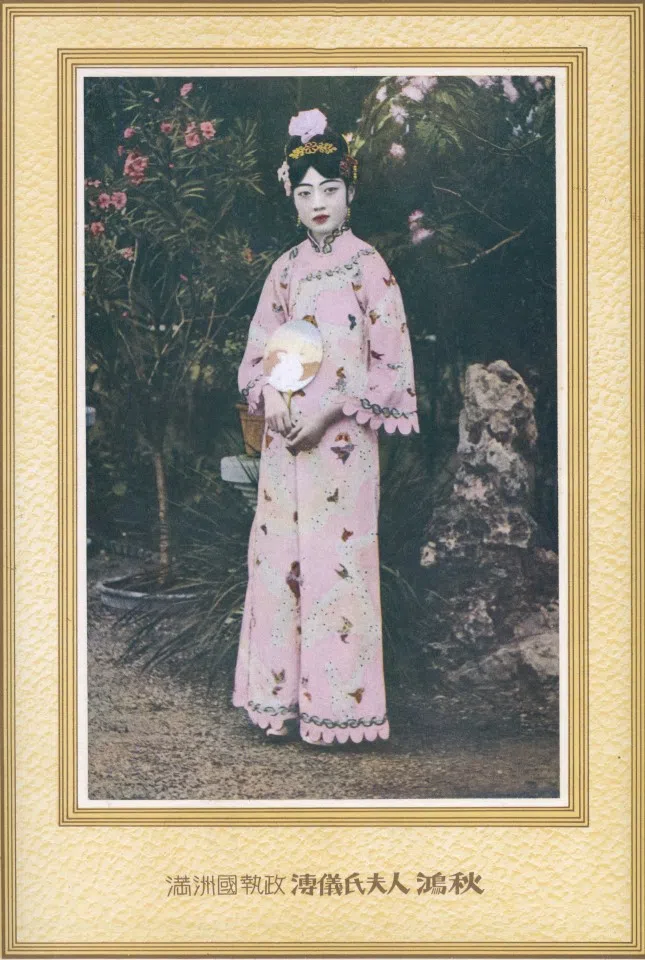

For Puyi, having his ancestors' mausoleum desecrated was definitely humiliating, and led to a lasting grudge between him and the ROC government. Then in his early 20s, Puyi was living in Tianjin with his wife Wanrong and concubine Wenxiu, leading a dissipated life by selling treasures taken out of the palace.

Subsequently, Wenxiu - influenced by modern thinking - no longer wanted to lead a bound life or share a husband, and decided to divorce Puyi; an emperor of old China signing divorce papers according to the law of the republic became a hot topic. This meant that the republican government no longer considered him a threat, while the Westerners also considered him sideshow news fodder.

The only exception was Japan's spy agency, which saw his irreplaceable value. They gave him decent lodging and treated him with courtesy, so that he felt for the first time the friendly warmth of a neighbouring country, amid the persecution of the ROC government. However, in fact, what Japan did was like the witch in the fairy tale, faking a smile while giving Snow White a glossy, red apple.

By 1910, Japan had completely swallowed up the Korean peninsula. Its next target was northeast China, commonly known as Manchuria. However, a straightforward military invasion would risk international intervention, and Japan needed to find a local ruler in name - Puyi and the Manchurian royals who had nowhere else to go were the ideal choice.

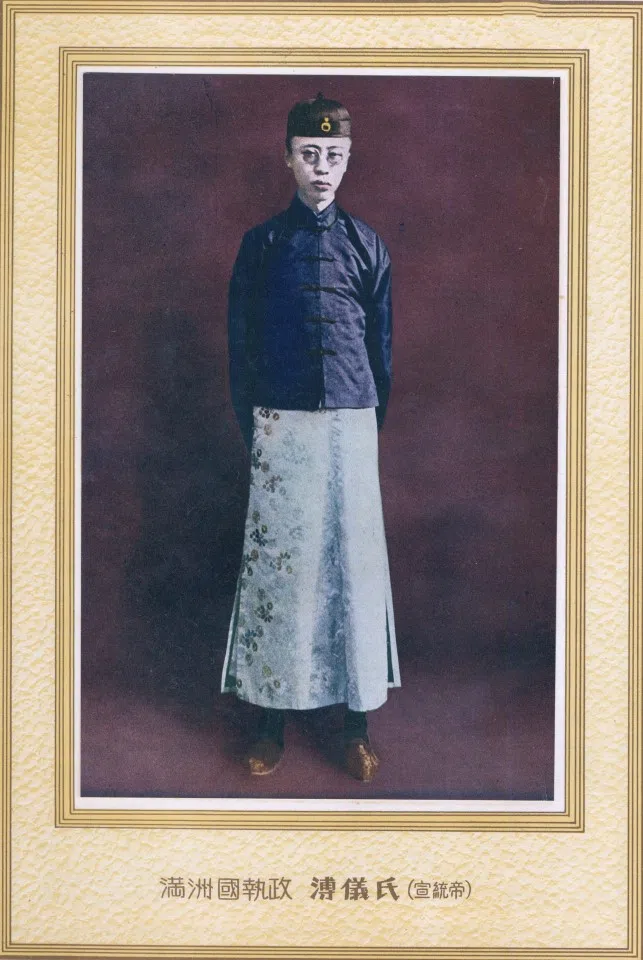

On 18 September 1931, the Japanese troops stationed at Shenyang in Liaoning, Manchuria, launched a sudden attack. Japan sent more troops, and within about four months had taken the whole of Manchuria. In November, the Japanese secret service secretly sent Puyi from Tianjin to Manchuria, and "Manchukuo" was soon proclaimed an independent state, and officially founded in March 1932. Puyi was made "regent", and it was not until two years later that he was allowed to use the title of "Emperor".

Meanwhile, China filed a complaint with the League of Nations about Japan's invasion. The League appointed the Lytton Commission, including diplomatic representatives of several countries, to go to Manchuria, Shanghai and Tokyo to investigate. The team conducted many interviews and gathered rich firsthand information, and released a complete report in October 1932 confirming Japan's invasion of China and also China's sovereignty over Manchuria, and not recognising Manchukuo as a sovereign state.

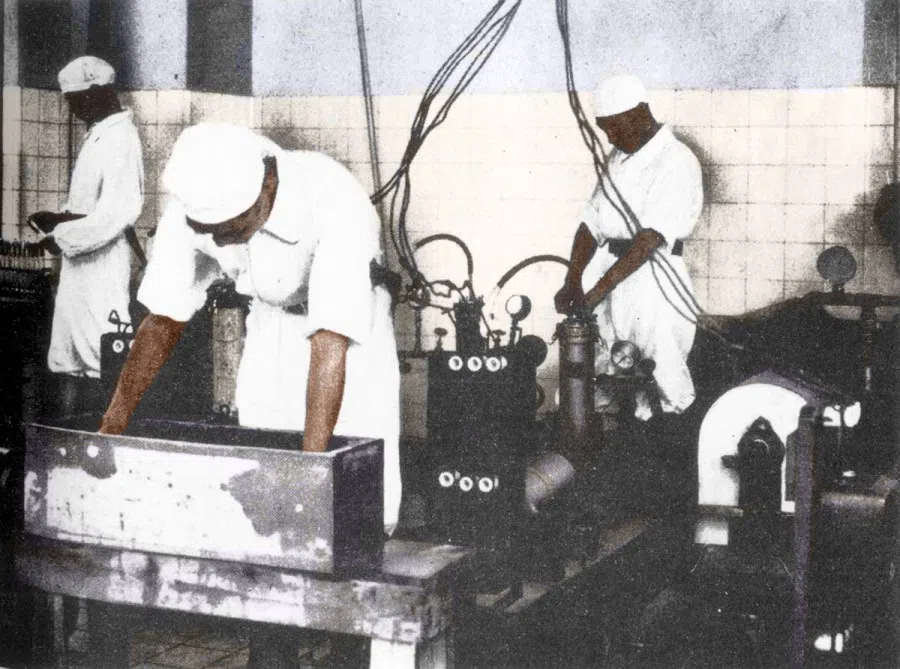

Subsequently, Japan pulled out of the League of Nations and became internationally isolated. Despite this, the Japanese government painted for its own people a rosy picture of Manchuria's development. Businesses flocked to Manchuria to set up branches, and the government arranged for entire villages of Japanese farmers to migrate to Manchuria, driving out the Chinese farmers and giving the most fertile land to the Japanese farmers. Japan set up large-scale industrial production, irrigation and transport facilities in Manchuria, and established Changchun in Jilin as the capital of Manchukuo, calling it Xinjing (新京).

A political puppet

Nevertheless, despite the seeming prosperity of Manchukuo, Puyi quickly became disappointed and disheartened. He and his followers had hoped that Manchukuo would have an opportunity to mediate the conflict between the Japanese and ROC governments, and make way for the Manchurian dynasty to rise again. However, the harsh reality soon hit home.

His every move was monitored by Japanese advisers, who arranged in advance whatever he did or said. He had zero personal freedom - a true political puppet. As for Wanrong, she detested what the Japanese did. Under severe depression, she became addicted to opium, and became pregnant through an affair, only for the child to be killed at birth. Wanrong was devastated.

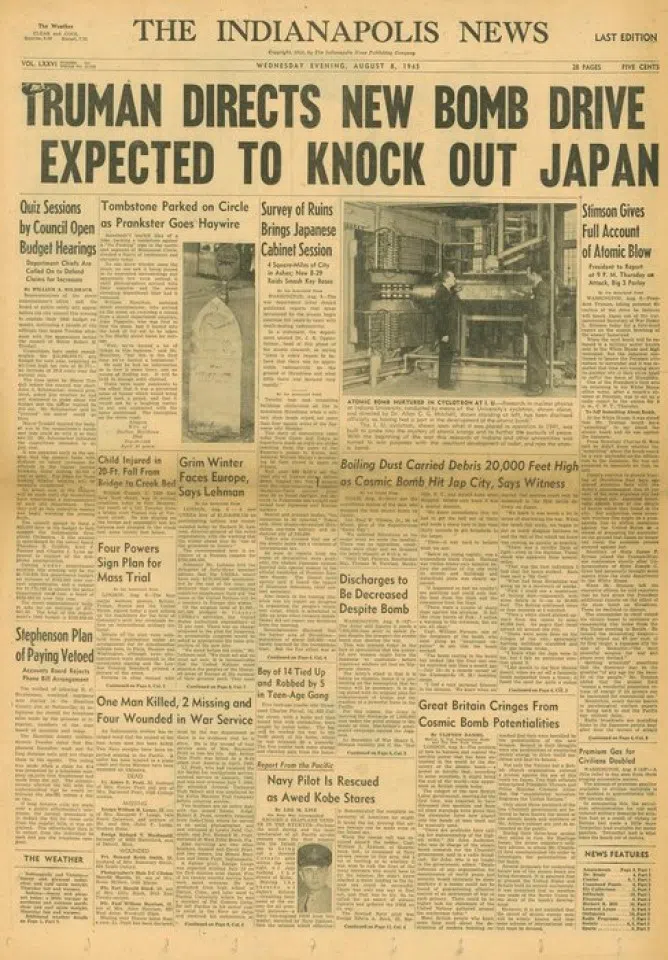

On 9 August 1945, three days after the US dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the Red Army launched a lightning strike on Manchuria. About a week later, Japan surrendered; in an instant, Manchukuo was no more. Puyi and other senior Manchukuo officials were arrested along with many Japanese army leaders and sent to the Soviet Union, which arranged for Puyi to appear as a witness before the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal during the Tokyo Trial following Japan's surrender.

Puyi said Manchukuo was an act of invasion completely orchestrated by Japan, and he could not make any independent decisions, denying his own responsibility and involvement in Japan's invasion. At this point, he resumed his identity as a Chinese.

In October 1949, the Chinese Communist Party won a complete victory in the Chinese civil war, and the People's Republic of China (PRC) was founded. In August 1950, the Soviet government transferred Puyi and over 200 Manchukuo prisoners of war to the PRC government. Puyi was tried and reformed, and imprisoned in Fushun Prison (now the Fushun War Criminals Management Centre) in what used to be Manchukuo. He was given a special pardon in 1959 and became a commoner, first as a gardener and ticket seller at the Beijing Botanical Gardens, and then at a historical research agency. While in prison, he related his experiences, which were later published as his memoir From Emperor to Citizen; the 1987 movie The Last Emperor was based on the book and won nine Oscars.

Soon after his release, Puyi married Li Shuxian, and the couple led a quiet life for a few years, before Puyi died of illness in 1967 at the age of 61. This closed the tragic life of the last emperor of China, officially ending imperial politics in China.

Related: [Photo story] The secret pre-World War II diplomacy between China and Germany | Jonathan Spence: A Western historian's search for modern China | [Photo story] The fate of Japanese POWs and civilians in China after World War II | [Photo story] The establishment of the People's Republic of China | [Picture story] The Boxer Rebellion: A wound in China's modern history | The Opium Wars: When China's 'century of shame' began

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)