Du Fu and tofu are not the same thing

Based on my university's guidelines, teachers are required to use English as the medium of instruction when teaching ancient Chinese literature to international students. It is a pretty interesting experience and often comes as a rude shock to teachers who think they have seen it all.

But more often than not, at least in my experience, puzzled students would raise their hands asking, "Is QY male or female? (This is the acronym of Qu Yuan's name and how students address the poet.)

We must never make these assumptions: since the students are already studying in university, surely they must have had some basic cultural knowledge and interest in the subject matter before they enrolled in the class? Wouldn't they be like Chinese students who give teachers free rein to teach, and understand that Qu Yuan's 香草美人 (lit. fragrant grass beauty, where grass refers to righteousness and being uncorrupted, while beauty refers to a gentleman) actually symbolises the poet's burdened heart for the future of his country and its people?

One always hopes that they would follow your train of thought and embark on an exploration of the soul together with you. But more often than not, at least in my experience, puzzled students would raise their hands asking, "Is QY male or female? (This is the acronym of Qu Yuan's name and how students address the poet. I get it. "Qu Yuan" is indeed a mouthful for international students.) Or they might ask, "What has fragrant flowers got to do with the future of a country?"

Du Fu and tofu are not the same thing. They're entirely unrelated.

The first time you're met with such an unbelievable teaching experience, you don't know whether to laugh or cry. You may still laugh it off as a case of cultural difference, and use it as a joke to share among colleagues. However, when you're met with such unbelievable experiences year after year, it isn't that hilarious anymore. It forces you to ponder: different systems of culture and tradition will crystallise into different sets of general knowledge accumulation. A thought system will then be nurtured, and over years of unconscious influence from what one sees and hears, unimaginable cultural barriers will be formed by the time the individual enrols in university.

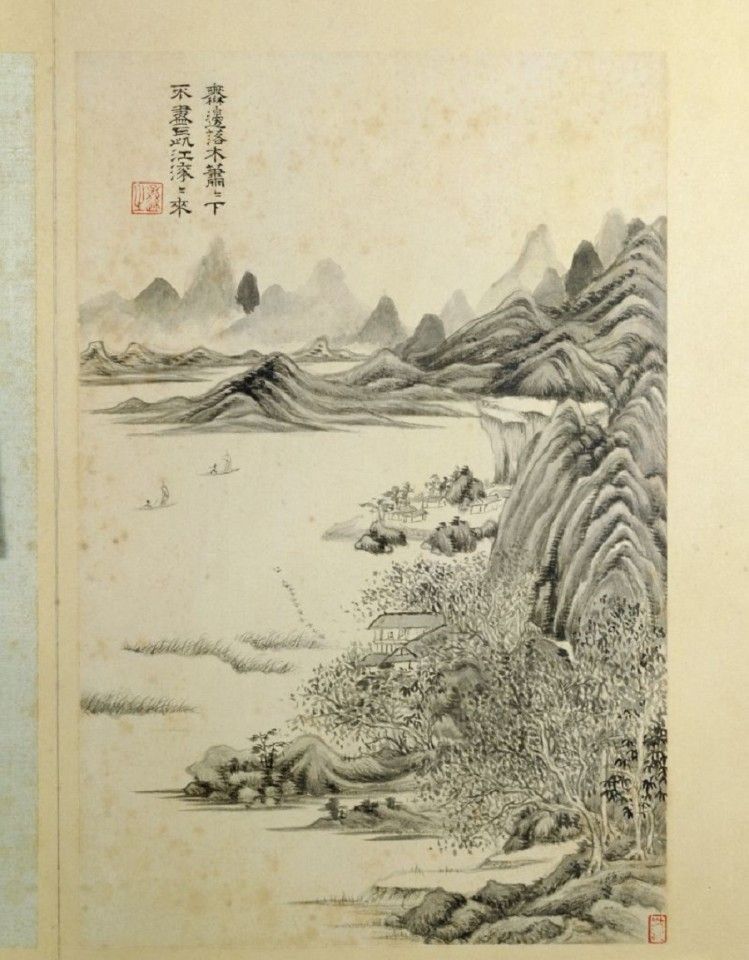

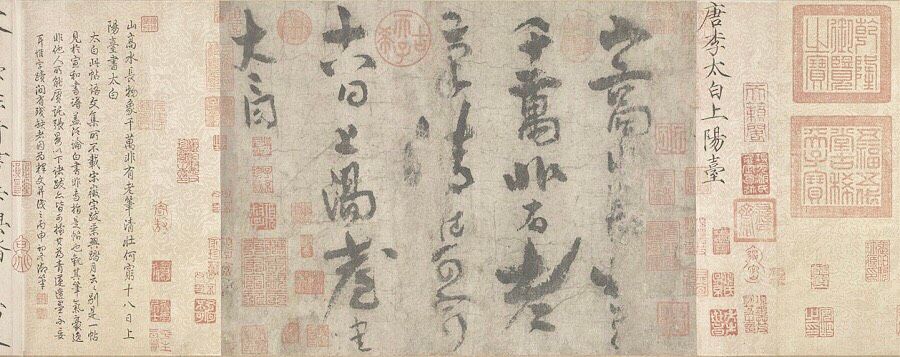

I was teaching Tang poetry once, and there were just so many Tang dynasty poets to talk about: the most famous ones were Li Bai and Du Fu, but many who belonged to the "major poets" category were not to be missed as well, such as Wang Wei, Bai Juyi, and Li Shangyin. In the process, an American female student raised her hand and asked, "I've never heard about Li Bai and the rest, but I do often hear about 'tofu' (she meant Du Fu) - was he the one who invented the edible tofu?" I knew straight away who she was referring to. She had mixed up the pronunciations of "Du Fu" with "tofu". I immediately told her, "Du Fu (and the Wade-Giles transliteration of Du Fu's name as 'Tu Fu' made it that much more like 'tofu') and tofu are not the same thing. They're entirely unrelated." "Oh," she replied, poised and innocent, flashing me a beautiful smile as a way of thanking me for my explanation.

Then a Japanese student raised his hand, "There's another famous Tang dynasty poet with a status no less than that of Li Bai's and Du Fu's. His name is Haku Rakuten. Why didn't you mention him?" Oh, Haku Rakuten, yes of course, that's the Japanese pronunciation of Bai Letian (Bai Juyi). He has been well-known in Japan since the Heian period. I went on to explain that Bai Juyi is the "Haku Rakuten" that he spoke of. "Bai" is "Haku" in Japanese, and represents his surname. "Juyi" is "Kyoi" in Japanese, and refers to his name. "Rakuten" is his courtesy name (an alternative name circulated among friends and fans), which translates to "Letian" in Chinese characters. "Haku Rakuten" is "Bai Juyi", that's right.

I explained that while "even grandmas could understand" the line "bright moonlight shining on bedside", the poem was not written by Haku Rakuten. It was written by Ri Haku (Li Bai).

I then realised: using English to teach Chinese literature was still manageable if my students only came from America and Europe. The worst mistake could be settled over a plate of tofu. For Japanese students, using English wouldn't work that well; Japanese pronunciation of Chinese characters is incompatible with hanyu pinyin (romanisation system of Standard Chinese). The mere untangling of proper nouns, a person's name, or the name of a place, would already take an entire day's work.

Perhaps the Japanese students felt that they were different from the American students who knew nothing at all. After all, they did study a few Chinese poems. The student continued by saying that Haku Rakuten's poems were easy to understand. He even read a few when he was in high school. He recalled a line: "Bright moonlight shining on bedside (床前明月光)." He said even grandmas could understand them. I explained that while "even grandmas could understand" the line "bright moonlight shining on bedside", the poem was not written by Haku Rakuten. It was written by Ri Haku (Li Bai).

Shocked by that realisation, they exclaimed, "Oh, the poet was Ri Haku?" In the midst of all the "hakus", the other students sank into a state of confusion. Perhaps thinking it was quite hilarious, a French student couldn't help but mutter "haku, haku" under his breath, but it didn't escape my ears. I was dying on the inside, worried sick that after a lesson on Tang poetry, the students went home with nothing but "haku, haku".

As a matter of fact, to say that Bai Juyi's poems are so simple that even grandmas can understand them is relative - it may not always be the case. Of course, his poems may be simpler compared to those of Han Yu (also a Tang dynasty poet). But Bai Juyi's poems contain various references to historical stories and characters. If you know nothing about these historical facts, you'll understand none of it - of course, you'd only be able to hum "haku, haku" and be like one of the blind men only knowing fragments of the story in the parable about the blind men and an elephant.

For example, he wrote a series of five poems entitled A Bold Declaration (《放言》) in conversation with his friend Yuan Zhen. A famous line often quoted by people reads: "周公恐惧流言后,王莽谦恭未篡时。向使当初身便死,一生真伪复谁知?"(Duke Zhou was afraid of rumours spreading around, while Wang Mang always kept a respectful facade before he usurped the throne. If they had died then, who would've known what the truth was?)

If one didn't know that Duke Zhou was later a model regent and that Wang Mang had usurped the throne, how would one be able to understand such a clear and simple poem? The international students whom I taught had no prior knowledge of these basic historical facts. I was left with no choice but to explain these stories first before teaching the actual poem.

My dear students, do you know about these two stories? If you don't, go flip through some books or search online, lest you let Haku Rakuten down.

And then it suddenly struck me that Hong Kong students were weak in their historical knowledge as well. They lacked the necessary cultural substance to appreciate poems and I couldn't help but wonder if they would also "haku" their day away if they came across Bai Juyi's poems that were so rich in historical allusions. I guess they ought to know (actually I'm not quite sure) what happened with Duke Zhou and Wang Mang.

Let's try another poem, one that Bai Juyi wrote to Yuan Zhen when he was demoted and relocated to Sichuan, a poem written to encourage him to not wallow in self-pity and to take good care of himself.

A line reads: "侏儒饱笑东方朔,薏苡谗忧马伏波。" (Midget Clowns laughed at Dongfang Shuo, while an uncorrupted Ma Fubo was defamed.)

Here, Bai Juyi alludes to the historical stories of Dongfang Shuo and Ma Yuan (Ma Fubo) to comfort his friend Yuan Zhen who was in a similar plight as them. My dear students, do you know about these two stories? If you don't, go flip through some books or search online, lest you let Haku Rakuten down.