An album of rare photos: From Chinese coolies to Singaporeans

From the 19th century to the 1920s and 1930s, ships transporting hundreds of Chinese coolies ready to work hard and make their "fortune" in Nanyang often docked at Kallang River. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao recently obtained an album with rare photographs of such a ship carrying coolies from Xiamen in Fujian, China, to Singapore in the early 20th century. They are an authentic visual record of Chinese coolies in Singapore a century ago and a powerful throwback to that period.

(All photographs courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

In 1978, Singapore’s then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew told visiting Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s reform and opening up, that if the descendants of unlettered, landless farmers who had migrated from Fujian and Guangdong to Nanyang could succeed, then surely China, with its intellectuals, scholars, and nobles who remained, could also succeed.

Based on Singapore's experience, Lee was encouraging China to boldly stride towards reform and opening up. However, his remarks also showed another layer of self-awareness: Chinese Singaporeans are not shy about their ancestors' humble background. On the contrary, looking at how they have progressed and what they have achieved today, those humble beginnings bring out the triumph of changing one's destiny through unceasing effort. Yesterday's poverty has become today's pride.

... out of this agricultural society grew the Chinese philosophy of life - hard work, conservatism and an emphasis on discipline and order.

Chinese coolies coming to Nanyang is an important marker in modern Chinese history. Historically, China was built on agriculture; the people were attached to the land and were reluctant to move around, and out of this agricultural society grew the Chinese philosophy of life - hard work, conservatism and an emphasis on discipline and order.

With the Yuan dynasty came maritime trade in China's southern and eastern coastal provinces. Merchants organised shipping expeditions seeking trade opportunities, and developed a national fleet of armed boats. However, it did not last long. During the Qing dynasty, the reigning Emperor Kangxi was a Manchu nomad who did not give much attention to maritime activities, but saw the sea as a place where enemies and criminals escaped and took cover. As a result, he banned people from going to sea.

At that time, the Chinese who came to Nanyang were generally part of a minority of merchants who travelled regularly, or nobles and soldiers who fled southward with the changing of dynasties, along with some commoners who followed them.

Nanyang - land of opportunity and hardship

After the mid-18th century, the Western powers gradually established colonies in Southeast Asia, which attracted some Chinese to move south to seek a living. A century later, Britain opened up tin mines in the Straits Settlements, and planted rubber and sugar cane to develop the economies of its colonies. It systematically recruited large numbers of Chinese and Indian workers to settle in the region. At the same time, China entered a period of unrest - villages declined and people were forced to cross the sea to make a living. The California gold rush and the Pacific Railroad in the US also attracted many Chinese workers, but before long, the US closed its doors to Chinese with the Chinese Exclusion Act. Given the international situation and geographical convenience, most Chinese workers headed to Southeast Asia. So began the difficult story of Chinese coolies seeking a new life in Nanyang.

From the 19th century to the 1920s and 1930s, most of the Chinese who migrated to the Straits Settlements were from Fujian and Guangdong, with those from Fujian leaving by sea from Xiamen. And although they were technically "contract workers", they bore the humiliating tag of "piglets" (猪仔), while the trade in Chinese labourers was known as "selling piglets" (卖猪仔), meaning that these workers were there to be sold and "slaughtered" like pigs. A glance into the coolie trade explains these labels.

"Agencies" rented boats and sent "agents" into the villages of Fujian and Guangdong to recruit workers. The impoverished villagers could not afford the tickets and agent's fees, and had to sign indentures or contracts, which they would repay with one or two years' worth of their wages. Under the rules of the colonial governments, the agencies would make a generous profit and pass on any surplus to the boat companies and agents. The agents would charge the workers costly advances on the boat fees, and charge interest according to the period of repayment. When the workers landed, the colonial governments or the agencies sold them to tin mining companies, rubber plantation owners, or other production companies that needed labour. Simply put, from the colonial governments to the agencies, from the boat companies to the agents, each of these entities earned a lot of money. And at the bottom of this "food chain" were the coolies - the "piglets".

Imagine: indentured workers crammed in the hold of a coolie ship, having to endure a long journey with only basic provisions and poor sanitation with no doctor if they fell ill. No wonder many died on board and never got to their destination. Even if they did, they were immediately put on overly long work hours, with their already meagre wages even more depleted to repay their debts. They worked hard every day for that moment of freedom when they could seek new opportunities. In fact, coolies were essentially slaves, and coolies heading to Nanyang were fundamentally victims of human trafficking.

And in the century or so where this trade took place, the colonial governments, boat companies, labour agencies, tin mining companies, rubber plantation owners, sugar cane plantation owners, banks - all of them grew rich and amassed significant wealth, while the economy of the colony prospered.

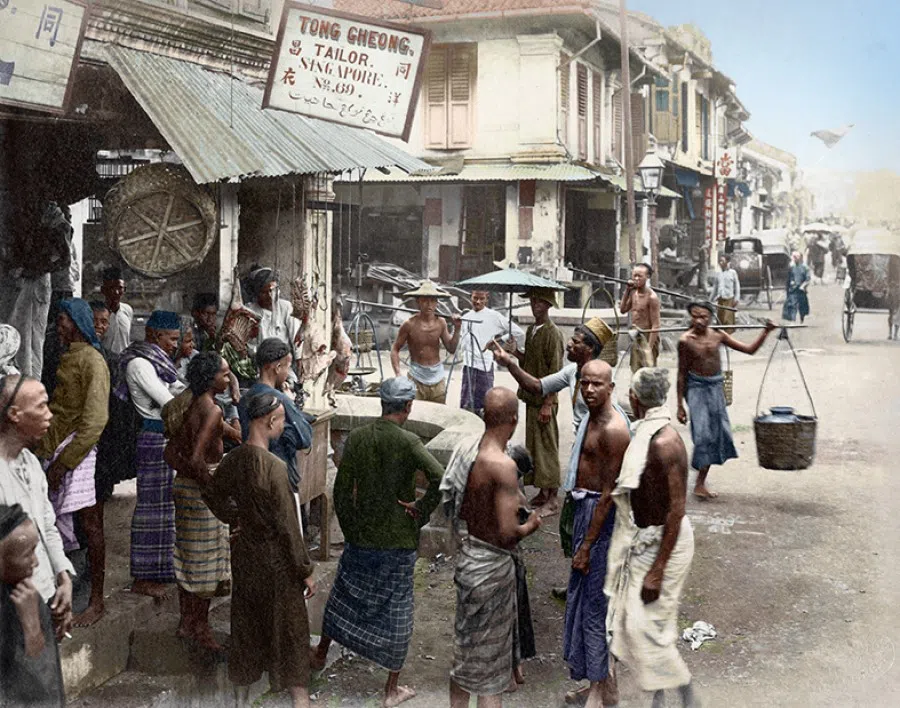

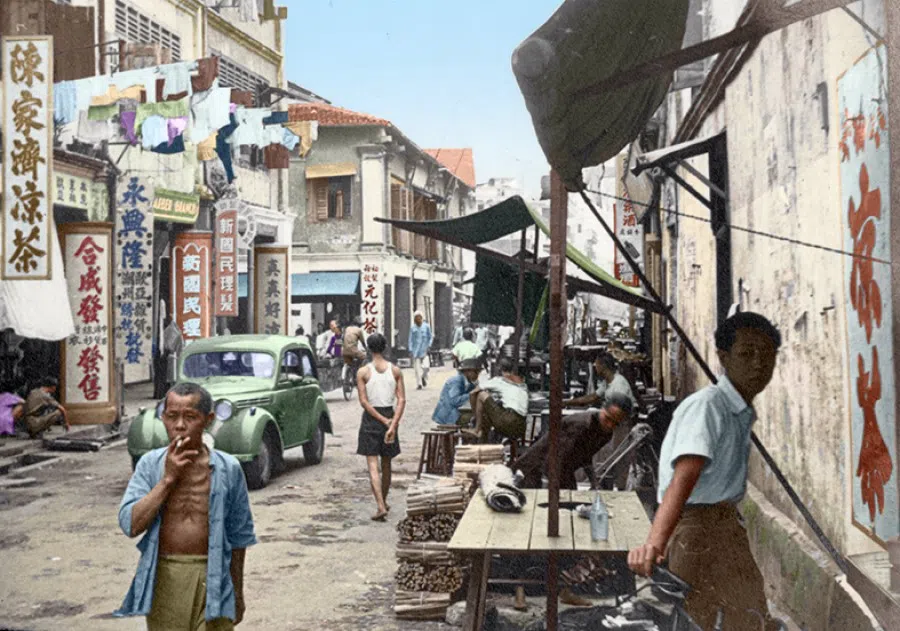

For the workers who made it through the do-or-die repayment period, they scrimped and saved, and started sending money back to their families in China. In a few years, perhaps they would head back home with armloads of gifts, then get married to a girl introduced by their elders, and bring her back to Nanyang. Their next generation would get a better education; the more capable ones would run a shop, restaurant or company. They would congregate and build thriving Chinatowns, including in Singapore.

Newfound confidence

Thriving commerce, development of light industry, finance, tourism and so on, attracted relatives of these early pioneers to join them in Nanyang. One generation later, their young people would go even further in their education; some got degrees in law, medicine, and business from prestigious universities in Britain, becoming the intellectual matches of the best elites in the West. With the sucess came newfound confidence. The people felt that they did not need colonial governance - they were perfectly capable of deciding their own destiny and creating their own progress. And all this began in the distant past, the moment when those ragged, lost coolies got off the boat and set eyes on this new land.

For China, this is a painful memory of how its people crossed the sea to eke out a living amid domestic and external troubles; for Chinese Singaporeans, the bitter process aside, it also marked a fresh start, a new environment and a new destiny. And, after generations of struggle and change, there emerged new objectives and a new sense of belonging.

Of course, walking around and looking at the modern tall buildings and wide streets of Singapore's Chinatown today, the traces of the past have long faded, and it is hard to imagine the influx of Chinese workers and crowded streets of a century ago; all of that seems to have happened in a foreign land in a movie, and it is difficult to connect it with what one sees now.

Having said that, while the physical bodies and the facades of buildings are no more, the hard work and grit of those workers a century ago, and their refusal to bow to their fate, have lasted through the ages and been passed down unceasingly through generations. In each chapter of Singapore’s history, its people have shown great strength in not fearing hardship and overcoming adversity.

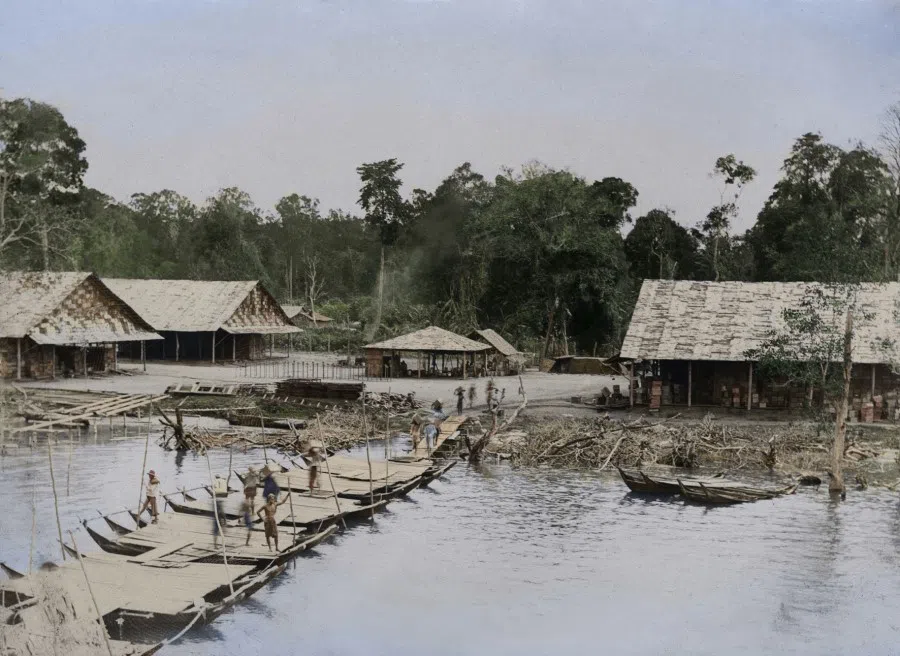

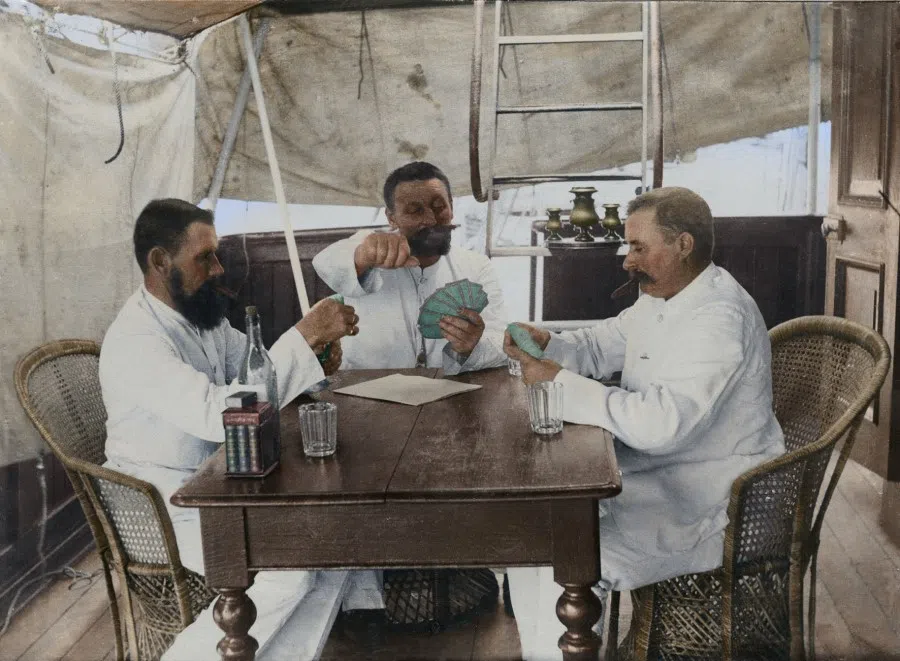

While there are many historical written records of Chinese coolies' life and times in Nanyang, there are few visual records. In its early days, photography was costly, and photography studios mostly took photographs of individuals and families as mementoes, or of buildings or nature to sell souvenir tourist albums; there was no incentive to take photographs of scruffy Chinese workers. Recently, I obtained an album with photographs of a ship transporting Chinese coolies from Xiamen in Fujian, China, to Singapore in the early 20th century. The photographs include impoverished Chinese workers on deck, the German shipowner and crew, the agent in charge of the Chinese workers as well as the women on board, the Western-owned compound the workers saw when they landed in Singapore, and the simple kampungs here. They are an authentic visual record of Chinese coolies in Singapore a century ago, a powerful throwback to that period.

Digital colouring: Chen Yijing, Feng Yuanshen, Xu Danyu, Xu Danhan

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)