[Photos] How Sichuan rose from a famine unbeknownst to the world to become a ‘Land of Abundance’ [Eye on Sichuan series]

From the Three Kingdoms and Xinhai revolution, to the establishment of communism in China and the Great Famine, Sichuan played significant roles in key parts of China’s history. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao shares photos of those turbulent times.

(Images courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao unless otherwise stated.)

Sichuan province in China has long been known as the “Land of Abundance”. The name “Sichuan” refers to the four rivers — the Yangtze, Jialing, Min and Tuo — that cut through the province’s mountainous terrain, creating a natural landscape where mountains and waterways intertwine. Due to its rich water systems, the region boasts a wide variety of flora and fauna, including the world’s only giant panda species, making it exceptionally well-suited for agricultural production.

Prominent role in wartime

As early as 2,500 years ago, this land gave rise to the Bronze Age civilisation in Sanxingdui. Sichuan had developed its unique form of civilisation independent of the Yellow River basin and separate from the mainstream Chinese culture.

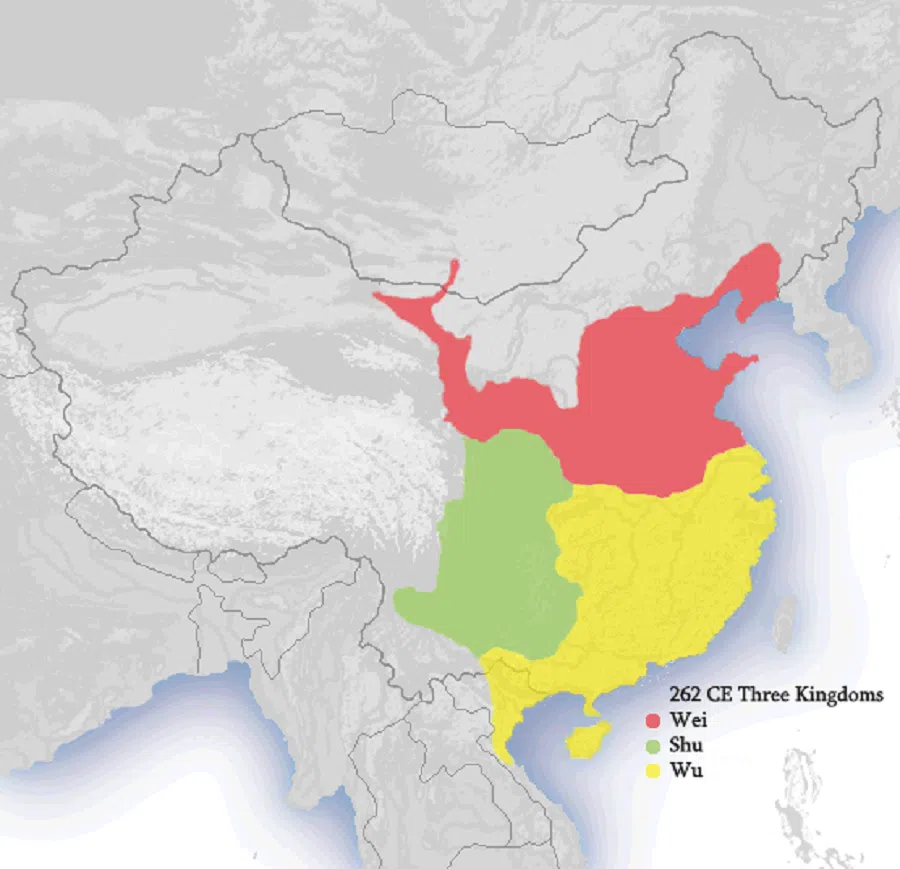

These naturally advantageous conditions shaped Sichuan’s developmental trajectory. During the Three Kingdoms period, Liu Bei — who claimed to be the legitimate successor to the Han dynasty — established the Kingdom of Shu in Sichuan. Together with Cao Wei, who held a strong military and many talented individuals, and Sun Wu, which had abundant resources from the Jiangnan region, the three formed the tripartite division known as the Three Kingdoms, a prominent narrative featuring Sichuan within China’s history.

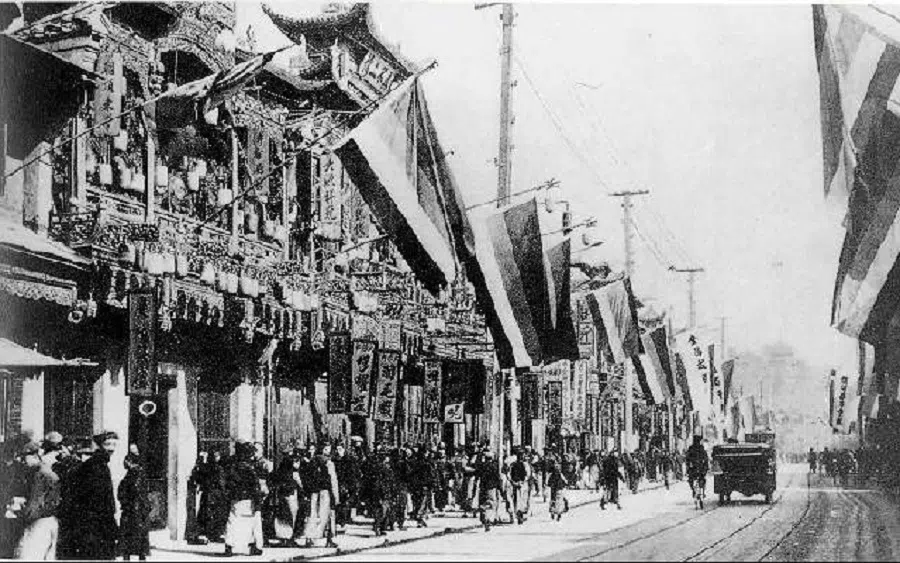

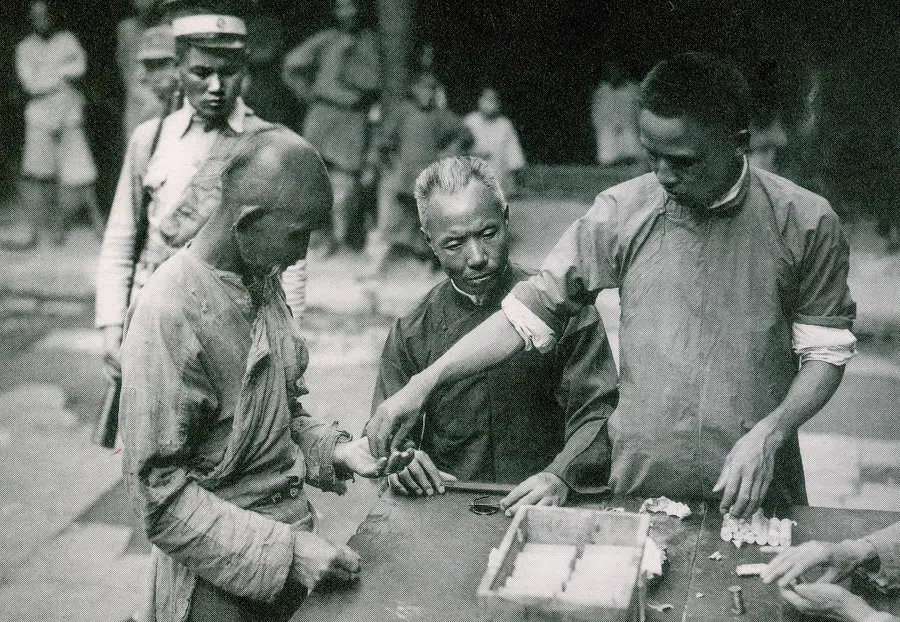

The Xinhai Revolution was sparked by the Railway Protection Movement in Sichuan, where people opposed the Qing government’s decision to nationalise the Sichuan–Hankou and Guangdong–Hankou railways, launching fierce protests that eventually led to a nationwide revolution.

Chinese civilisation also influenced neighbouring countries such as Korea, Japan and Vietnam, where stories and characters from Romance of the Three Kingdoms are widely known and enthusiastically discussed. Their emotional connection to ancient China is comparable to the Western attachment to ancient Greece and Rome; characters from the Three Kingdoms evoke the same kind of cultural resonance as Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and Caesar Augustus do in the West.

Sichuan has played an even more prominent role in modern Chinese history. The Xinhai Revolution was sparked by the Railway Protection Movement in Sichuan, where people opposed the Qing government’s decision to nationalise the Sichuan–Hankou and Guangdong–Hankou railways, launching fierce protests that eventually led to a nationwide revolution.

During the Republican era, Sichuan became China’s main rear base during the war of resistance against Japan. Following the outbreak of full-scale war by Japanese forces, the Chinese government was advised by the German military to buy time by giving up territory, retreating from eastern China to the southwest. This would help to exhaust the Japanese military and achieve a strategic stalemate, while awaiting favourable changes in the international situation to seize a strategic time to launch a counteroffensive.

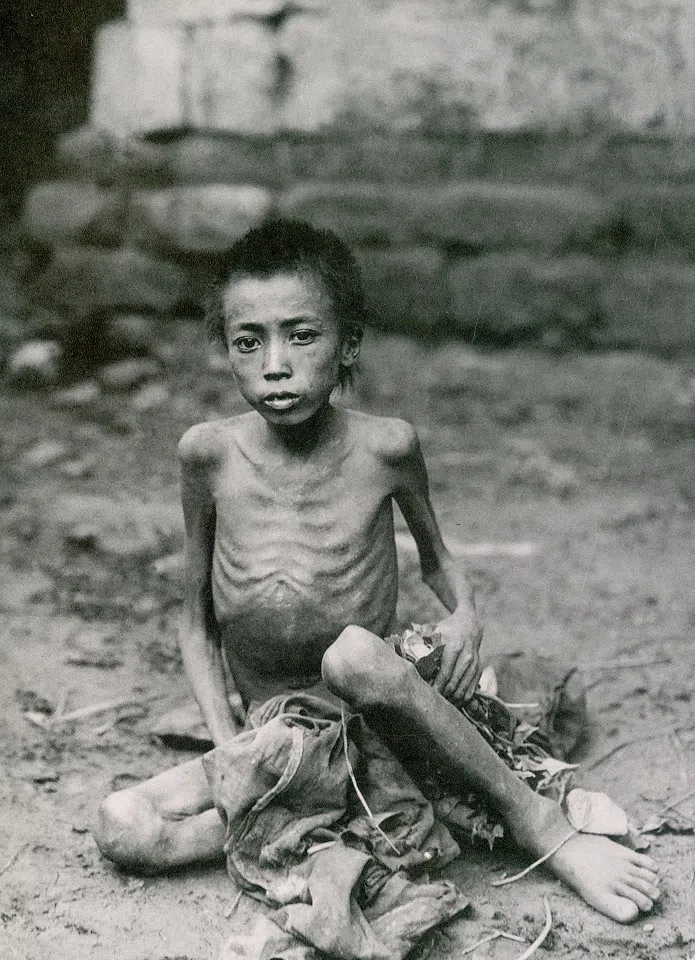

... in 1936 to 1937, before the war of resistance against Japan, Sichuan experienced a famine that shocked the nation.

Starving people fleeing

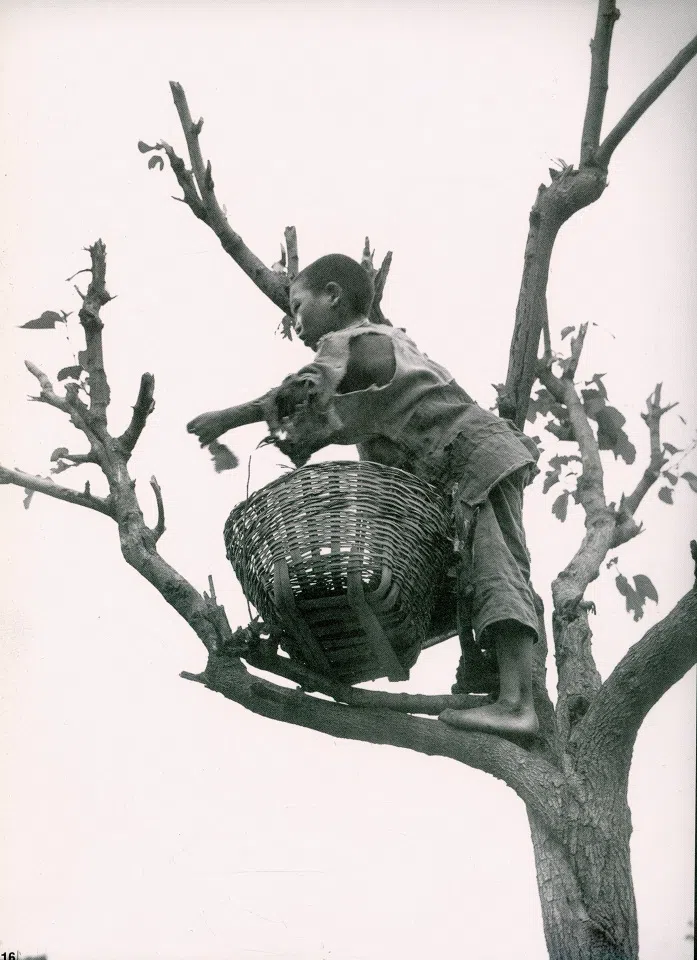

At the same time, in 1936 to 1937, before the war of resistance against Japan, Sichuan experienced a famine that shocked the nation. Due to months of severe drought, crops failed and hunger was widespread. At the time, transportation was poor, communication with the outside world was limited, and no relief supplies were delivered to the famine-stricken areas. Starving people fled Sichuan, wandering across regions, eventually drawing public attention to the crisis.

The central government dispatched journalists to report on the situation in the famine zones — it was only then that the country was made aware of the devastating disaster. Images of emaciated people appeared in the national media, prompting the central government to initiate relief efforts.

In a park in Zhuning county, Sichuan, there stood a tree with its bark peeled away to expose the white inner wood. Below it was a memorial plaque with the inscription: The Tree of Famine.

“In the 25th year of the Republic (1936), autumn harvests failed, followed by months of dry winter. Wheat and vegetables withered, and many people died of starvation. They stripped tree bark and dug up roots for sustenance. This tree in the park could not be spared, and what remains is its scarred trunk. It is preserved as a record for those studying social phenomena, and to serve as a warning to officials and policymakers.”

— Inscribed by Li Yijun, a native Zhuning county, Sichuan, and director of the county public library, guardian of the park.

After the Chinese government relocated the temporary capital to Chongqing, industrial and economic resources from eastern and northern China shifted to Sichuan.

Benefiting from relocation of capital

By 1938, not only had Sichuan emerged from the famine, but it also seized a rare development opportunity. After the Chinese government relocated the temporary capital to Chongqing, industrial and economic resources from eastern and northern China shifted to Sichuan. The province became a national hub for political, military, economic and cultural talent.

Large-scale industrial production was established, including defence manufacturing, machinery, parts production and processing industries. Sichuan rapidly gained significant economic weight and became a major economic province. The entire Chinese war effort came to rely on Sichuan’s economic operations.

Of course, all diplomatic envoys of the Allied nations were stationed in Chongqing, and a lot of Allied supplies and technical aid was transported directly to Sichuan.

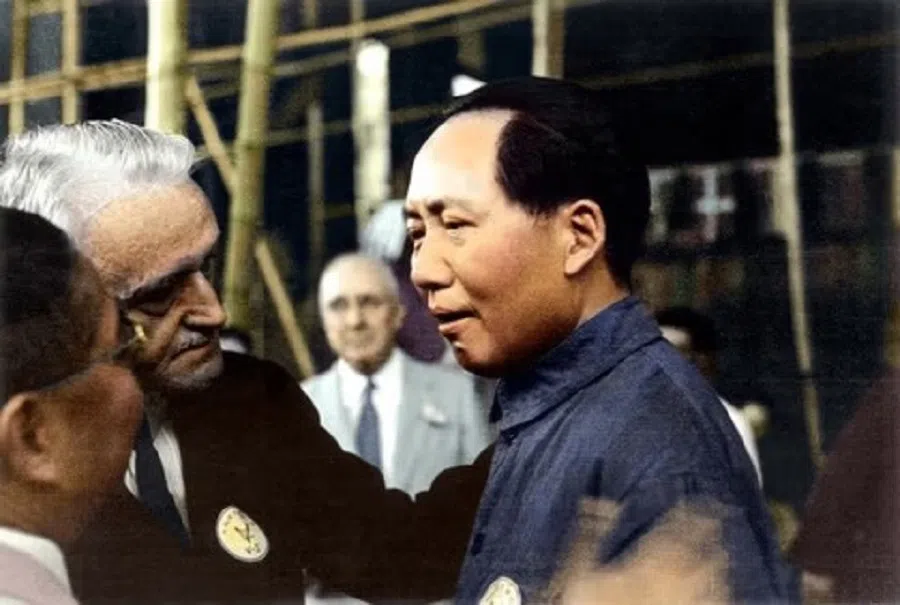

Even in the two years following the war of resistance against Japan, before China officially moved its capital back to Nanjing, the government continued to operate out of Chongqing for another year as an extension of the wartime administration. For instance, the negotiations between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) — including several meetings between Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong — were held in Chongqing. Political consultations between the two parties were also carried out there. It was not until after 1947 that China’s political centre formally returned to Nanjing.

During the subsequent Chinese civil war, the Nationalist forces, suffering repeated military defeats, eventually retreating to Sichuan in hopes of replicating the wartime strategy of using the province as a base for counteroffensive.

However, this effort failed. Unlike the fight against foreign invasion, the civil war was a domestic struggle to determine which political party could better resolve the issues of production and distribution within China. In the end, it was the CCP with its rallying cry of land reform that emerged victorious.

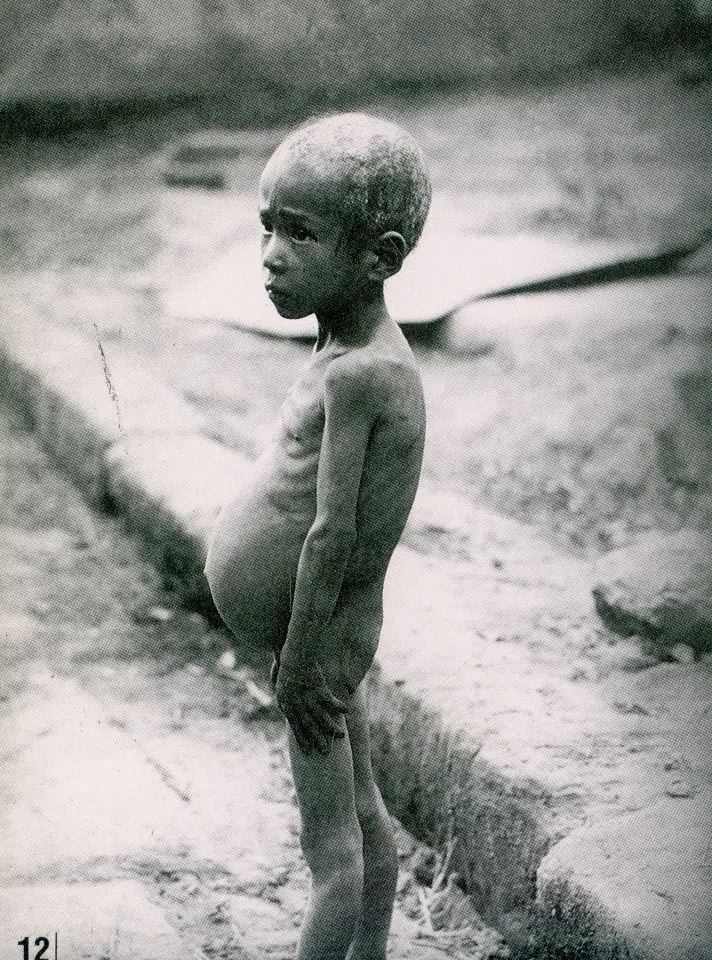

This extreme leftist dogma led to a devastating famine, eerily reminiscent of the tragedies under Stalin’s agricultural policies.

Now a thriving metropolis

After the establishment of communist China, land reform became a top priority. However, the land that had initially been distributed to tenant farmers was soon reclaimed by the government under the name of “public-private partnership”, and both land and businesses were nationalised.

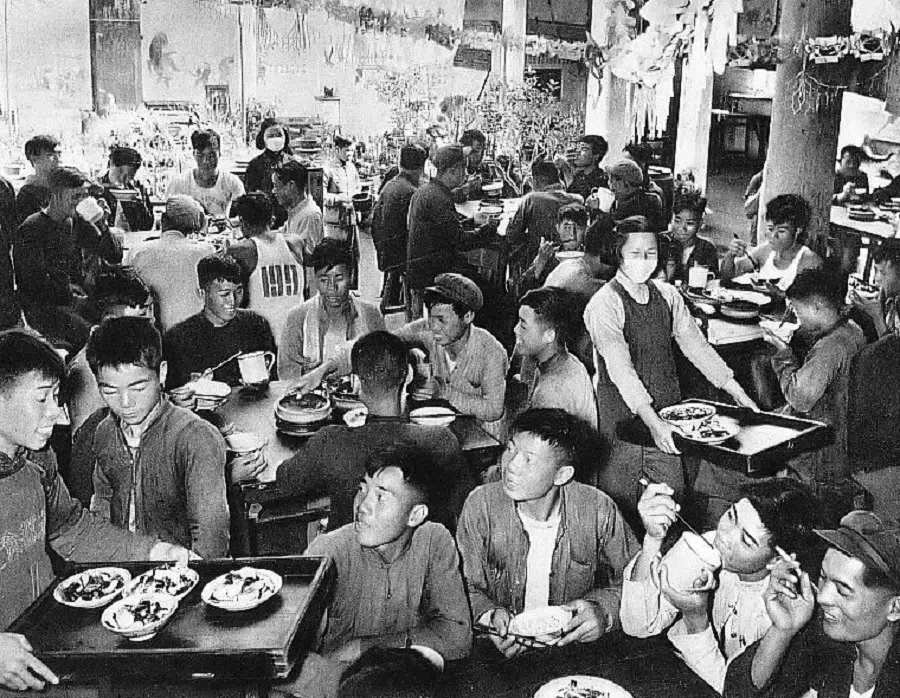

From 1959 to 1962, during the Great Leap Forward, the state pushed for a rapid transition into socialism by promoting Stalinist-style collectivised farms and setting up people’s communes, touting a utopian era with free meals. This extreme leftist dogma led to a devastating famine, eerily reminiscent of the tragedies under Stalin’s agricultural policies.

Sichuan, being one of the most populous provinces, saw an estimated ten million people dying of starvation. This was the most catastrophic famine in modern Chinese history, and it occurred during peacetime. Due to the lack of transparency, photographs documenting the famine in Sichuan are virtually nonexistent or have never been made public.

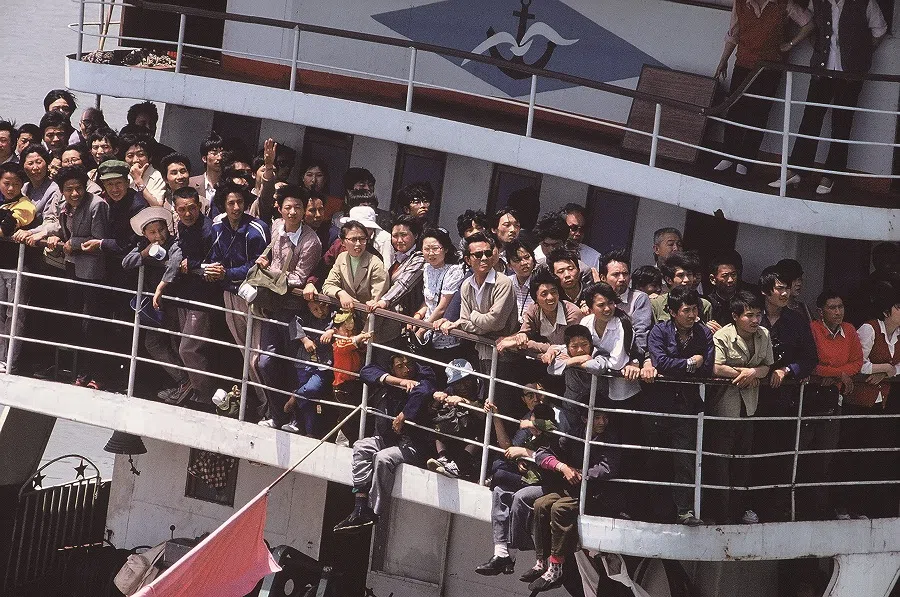

With the end of extreme leftism, Sichuan, like the rest of the country, entered the grand era of reform and opening up. With its massive population, a wave of Sichuanese workers sought jobs outside the province, becoming a vital part of the labour force in cities across China. Their goal was to gradually improve the living standards of their families back home.

Not only have major cities like Chongqing and Chengdu made extraordinary strides, but rural areas also diversified, developing local tourism and cultural industries beyond traditional agriculture.

Meanwhile, Sichuan itself underwent rapid development, creating new employment opportunities. Those who had moved away for work returned to start their own businesses.

Not only have major cities like Chongqing and Chengdu made extraordinary strides, but rural areas also diversified, developing local tourism and cultural industries beyond traditional agriculture.

Looking back over the past century, the story of Sichuan’s development serves as a powerful example of the progress made in China’s southwest. It reflects the broader national experience, yet also retains its unique characteristics, and is filled with moving stories that continue to resonate.

![[Big read] Prayers and packed bags: How China’s youth are navigating a jobless future](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/16c6d4d5346edf02a0455054f2f7c9bf5e238af6a1cc83d5c052e875fe301fc7)