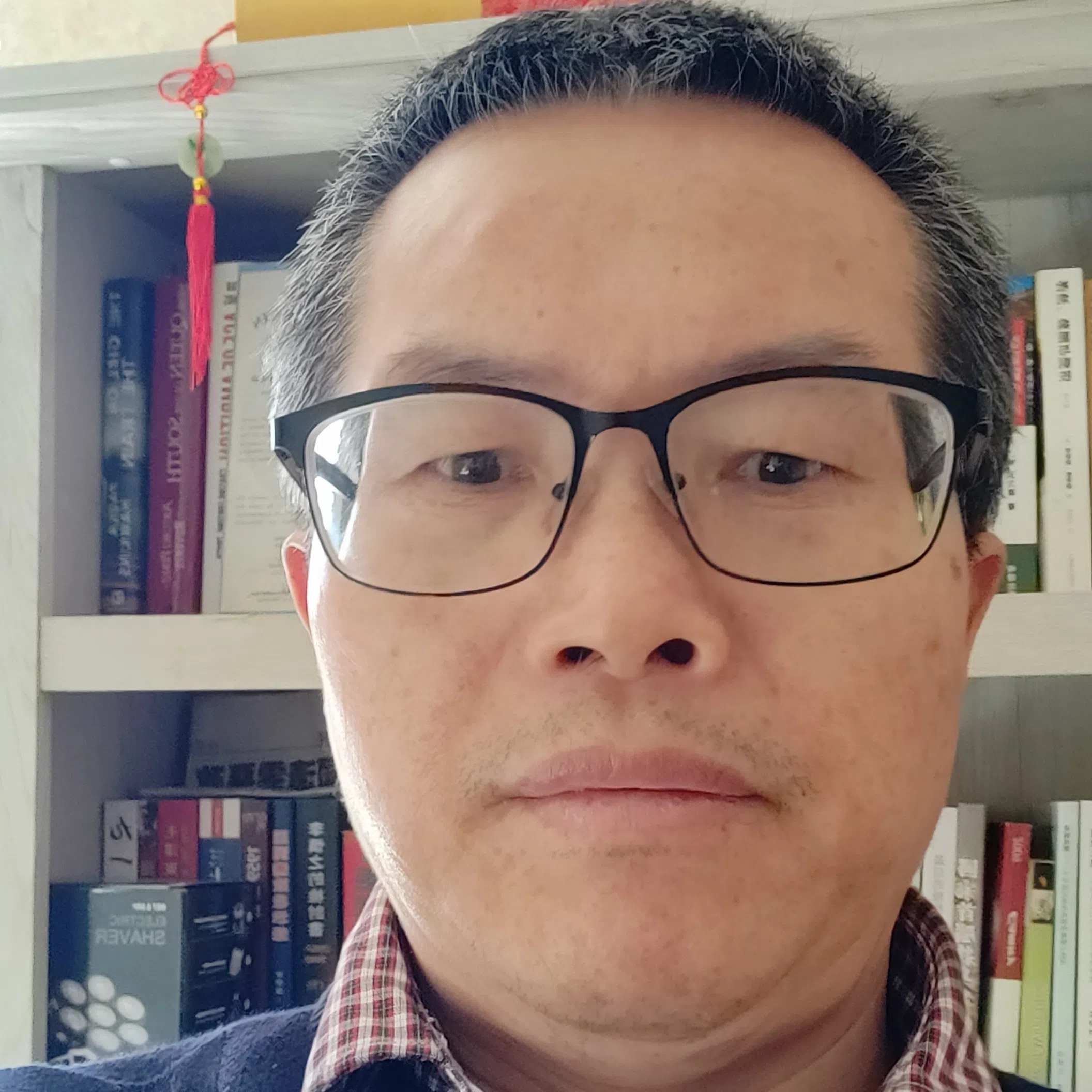

He Weidong: The general who tested Xi Jinping’s ultimate taboo

The abrupt removal of several top generals in China’s People’s Liberation Army — among them, Central Military Commission Vice Chairman He Weidong — points to deep unease within the ranks. Yet the cryptic language of official announcements offers few clues about what triggered the purge. Commentator Deng Yuwen unpacks the hidden logic behind He’s fall from power.

Before the CCP’s Fourth Plenary Session, China’s military abruptly announced the disciplinary and investigative outcomes for nine generals — among them, Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) He Weidong — signalling that He’s case has finally concluded. Though his downfall had long been anticipated, the authorities’ prolonged silence left observers unable to confirm whether he would indeed be punished.

He had vanished from public view for seven months following the National People’s Congress earlier this year — an unusually long absence that fueled speculation about his fate. Yet, unlike previous cases in which the military first declared that an officer had “seriously violated political discipline” and was “under investigation,” this time officials directly released the results of the inquiry, indicating that the probe into He’s case is now complete.

So when did the investigation into He actually begin? It likely did not start only in March. At the very least, by the time the military announced last year that CMC member and former CMC Political Work Department director Miao Hua was under investigation, He had already been drawn into the net. As Miao’s direct superior, He could hardly have avoided implication once Miao was in trouble.

Generally speaking, cases involving senior military officers are handled with far greater secrecy than those of party or state officials.

Shrouded in secrecy

It was likely only before this year’s National People’s Congress that investigators had yet to uncover conclusive evidence against He — or, more plausibly, they already had but allowed him to attend to avoid the shock of a CMC vice chairman’s sudden absence. Letting him appear was a calculated move to stave off speculation. After the congress, he vanished completely from public view.

Although the military’s announcement stated that He and eight other generals were expelled from the party and the military for “serious duty-related crimes” involving “particularly large sums”, “extremely serious nature”, and “extremely vile impact”, it offered no details on what those crimes actually were.

Generally, cases involving senior military officers are shrouded in far greater secrecy than those of party or state officials. Civilian court verdicts sometimes disclose offense details, but the crimes of PLA officers are rarely made public. Official accounts rely on political euphemisms rather than concrete facts, leaving the public with little sense of what actually brought these generals down.

Disloyalty to Xi Jinping?

Even so, the opaque official language allows some clues. Following the announcement of the nine generals’ punishment, the PLA’s authoritative mouthpiece, PLA Daily, published a strongly worded editorial titled “Resolutely Carry the Fight Against Corruption in the Military Through to the End”.

It accused the nine of “betraying their original mission and losing party principles, succumbing to ideological collapse and disloyalty, gravely betraying the trust of the Party Central Committee and the CMC, seriously undermining the principle that the party commands the gun and the CMC chairman assumes overall responsibility, gravely damaging the military’s political ecosystem, and severely shaking the ideological foundation of unity and progress across the ranks.”

When connected with “seriously undermining the principle that the party commands the gun and the CMC chairman responsibility system”, the implication becomes clear: it signals disloyalty to Xi Jinping.

Among these phrases, the key expressions are “ideological collapse” and “disloyalty”. The former concerns a breakdown of belief in party ideals — a loss of faith that often accompanies or rationalises corruption. The latter points to a breach of political loyalty — not merely disloyalty to abstract doctrines but to the organisation and, concretely, to the CMC chairman himself. When connected with “seriously undermining the principle that the party commands the gun and the CMC chairman responsibility system”, the implication becomes clear: it signals disloyalty to Xi Jinping.

Disloyalty, but to what extent?

If He Weidong engaged in corruption, that would not be surprising at all.

Despite Xi Jinping’s vigorous anti-graft campaign, with almost one senior official falling every two days, not even a CMC vice chairman can be presumed clean. After all, two former CMC vice chairmen and two former defence ministers have already fallen. But what does “disloyalty to Xi” specifically mean?

The term “disloyalty” has become a recurring accusation since the CCP’s 20th Party Congress. In the context of Chinese politics, it carries two connotations. One is moral: corrupt officials have betrayed the oath they swore upon taking office. The other is political: they have betrayed Xi’s personal trust.

Xi elevated them to high office not for personal enrichment but to serve the people and the party; their corruption therefore violates his confidence. However, this does not necessarily mean that these fallen officials actively committed acts of betrayal against Xi personally, though it cannot be ruled out that a few might have done so.

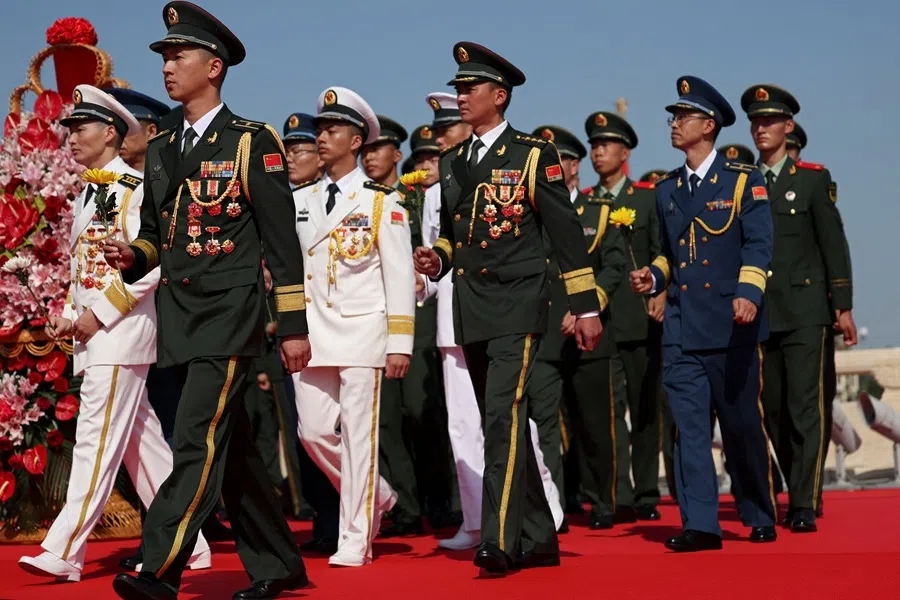

Still, when the PLA Daily links “disloyalty” with “seriously undermining the party’s command of the gun and the CMC chairman responsibility system,” the implication is far more serious. The principle that “the party commands the gun” is the very foundation of the PLA’s existence, while the “CMC chairman responsibility system” stands as the supreme political doctrine of the Xi era.

To “seriously undermine” either suggests something graver — perhaps even an attempt at “the gun commanding the party.” In CCP history, that phrase has always implied rebellion; in modern terms, an attempted coup. And if nine generals were involved, their target could only have been the CMC chairman himself.

Moreover, senior military officers today are under constant surveillance, leaving virtually no chance of success for a coup attempt.

It is conceivable that some within the CCP might harbour thoughts of a coup; otherwise, there would not be so many persistent rumours. But most officials with such impulses lack the means to act, as they have neither the conditions nor the capability. Military officers, however, are different: they command troops and, in theory, possess the means to rebel. The nine fallen generals include not only a CMC vice chairman but also commanders of theaters and service branches. In theory, therefore, they would have the capacity to mount a challenge.

Nevertheless, in He Weidong’s case, the possibility of rebellion can be ruled out. First, from the standpoint of Chinese political orthodoxy, rebellion has always been a heinous crime punishable by death and collective extermination. Second, He was regarded as one of Xi’s most trusted military confidants, elevated to a position “second only to one man.” He thus had no motive for rebellion.

Moreover, senior military officers today are under constant surveillance, leaving virtually no chance of success for a coup attempt. Therefore, “seriously undermining the party’s command of the gun and the CMC chairman responsibility system” likely refers instead to factionalism, with He, Miao, and others forming cliques behind Xi’s back in matters of personnel selection and promotion. Both men were in charge of the PLA’s political and organisational work, and placing trusted followers in key positions would not have been difficult.

Looking back at Chinese history, emperors often tolerated corruption among favoured confidants, so long as it did not provoke public outrage.

Violating the supreme leader’s ultimate taboo

One major function of Xi’s anti-corruption drive has been to eliminate factions within the party. Today, only the top leader may maintain his own small circle; other senior officials, even those considered close to him, may not emulate that practice. If they do, if they build their own networks, they will be accused of “forming cliques” and violating party discipline.

Of course, it is unrealistic to expect that high-ranking officials will never install their own trusted associates. The key is not to let the supreme leader detect that anyone is building a private faction that disturbs the balance of political ecology within the military.

Such behavior would be seen as a challenge to the leader’s authority. Whether or not these officers intended such a challenge, the effect would be the same. The nine generals taken down this time all hailed from the former 31st Army — enough, by CCP standards, to constitute a factional “small group”.

He Weidong most likely triggered the top leader’s alarm about factional formation, which may be the real reason he was investigated. Corruption could also be part of it, but if he had not formed a factional network, mere corruption — unless of astronomical magnitude — would likely not have warranted such harsh treatment.

Looking back at Chinese history, emperors often tolerated corruption among favoured confidants, so long as it did not provoke public outrage. But if a trusted aide built a power base that threatened the throne, the emperor would strike ruthlessly to eliminate the danger.

The PLA Daily editorial’s emphasis that “the entire military at all levels must unswervingly uphold the party’s absolute leadership, remain loyal to, support, defend, and safeguard the core” implicitly conveys this message. It suggests that He Weidong’s real offence was not merely corruption, but violating the supreme leader’s ultimate taboo on loyalty.