Policy, not palace intrigue: The real focus of China’s fourth plenum

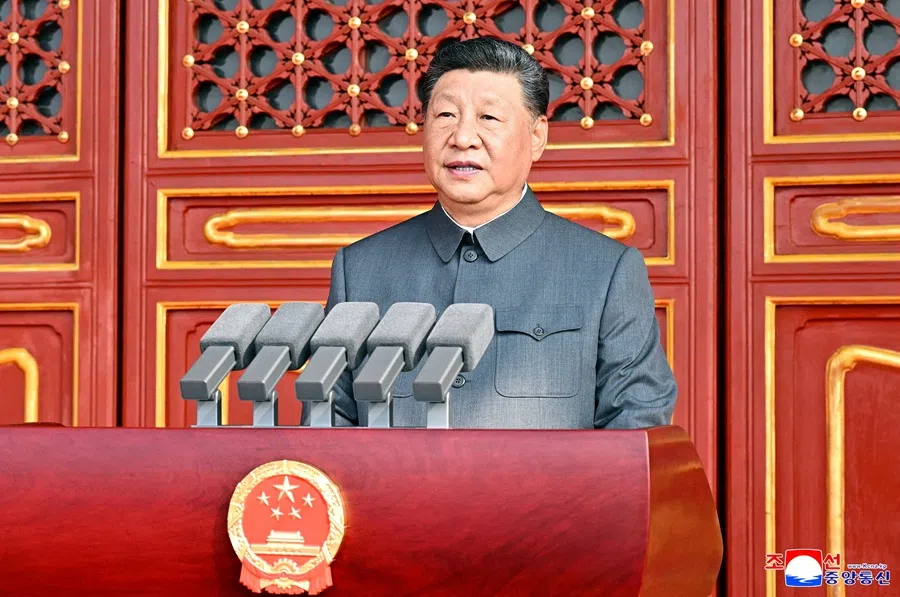

Despite the crackdown on corruption over the past year, the fourth plenum will not be a personnel session but a policy session centred on the 15th Five-Year Plan. Commentator Deng Yuwen notes that unless there is a sudden political upheaval in the coming days, economic and social strategy will take centre stage, while personnel issues remain secondary.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s Fourth Plenary Session is just a week away. From the perspective of elite power struggles, many observers naturally assume that this plenum will bring a major reshuffling of the leadership.

Some, especially overseas Chinese-language media outlets, have even gone so far as to claim that there will be a “three down, three up” shift in the Politburo Standing Committee. This echoes the recent rumour that CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping has “stepped back into a second-line role” (rather than having stepped down). Whether or not such talk serves particular purposes, the fact is that it is far removed from observable reality.

Every regime operates within certain rules. If one thinks there is no logic, it is only because one has not yet discerned the patterns.

Little political drama

Some argue that under Xi, power struggles are so fierce, and personnel and policy changes so unpredictable, that common sense and conventional logic no longer apply. I find this the perspective of outsiders unfamiliar with the workings of CCP politics. Every regime operates within certain rules. If one thinks there is no logic, it is only because one has not yet discerned the patterns.

Xi’s era is indeed very different from that of Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao or even Deng Xiaoping. But once new realities take shape, they rest upon their own internal logic. Failing to see this and dismissing it as disorder is intellectual laziness that easily leads to distorted judgments.

The fourth plenum is not a venue for replacing Politburo or Standing Committee members, let alone carrying out a dramatic “three down, three up” reshuffle. In other words, there will be no major personnel agenda. Like most other plenums, it will be largely uneventful, offering little political drama.

In fact, if we look back at the CCP’s plenary sessions, the pattern is quite clear. After each five-year party congress, the first and second plenums are dedicated to personnel and institutional arrangements. The first plenum elects the central leadership, including the Politburo, its Standing Committee and the Secretariat. The second plenum then discusses the composition of the State Council and other state institutions. This has been a fixed pattern for decades.

From the third through the sixth or sometimes seventh plenums, each session focuses on a specific theme: the third plenum usually centres on reform and economic policy; the fourth often on law or governance; the fifth on drafting the next Five-Year Plan; the sixth on party-building; and the seventh on preparing for the next party congress.

This functional division has become an institutionalised convention. In other words, unless there is an extraordinary situation, the agenda of the third through seventh plenums is predetermined and not primarily about personnel matters, certainly not about reshuffling the Politburo or Standing Committee. This year’s fourth plenum, postponed because the third was delayed by a year, will centre on drafting the 15th Five-Year Plan.

The lesson is clear: plenums become instruments of personnel change only at moments of major crisis, without which there will be no major reshuffle.

Past reshuffles and extraordinary circumstances

That said, history does provide a few examples where a plenum addressed major personnel changes — but only in the context of political crises or open power struggles. The most notable case was the fourth plenum of the 13th Central Committee in 1989.

In the aftermath of the Tiananmen crackdown, CCP General Secretary Zhao Ziyang was removed, and Jiang Zemin was elevated to the position, a personnel adjustment forced by political crisis. Earlier, during Mao Zedong’s era, the Eighth Central Committee’s eighth plenum purged Defence Minister Peng Dehuai, and the Ninth Central Committee’s fourth plenum confirmed the Lin Biao incident. These were all extraordinary circumstances.

The lesson is clear: plenums become instruments of personnel change only at moments of major crisis, without which there will be no major reshuffle. Today, while the crackdown on corruption continues amid struggles among the elites, it has become routine and does not constitute a sudden political crisis. Anti-corruption, though deeply disruptive, is now built into Xi’s mode of governance, and thus does not justify dramatic personnel changes at this plenum.

If major reshuffling is off the table, what about the widely rumoured cases of He Weidong and Ma Xingrui? Is there a chance their situations will be revealed at the fourth plenum? This is very unlikely. Both cases are indeed unusual.

He Weidong, a Politburo member and vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission, has been conspicuously absent from multiple important events and meetings since the Two Sessions, including the recent National Day reception. Some have suggested illness, but this cannot explain why his name was also missing from the wreath lists for deceased former leaders — a matter that requires no physical presence.

Meanwhile, Ma Xingrui was removed as party secretary of Xinjiang in July with the official explanation being “assigned to another post”. Yet, nearly three months have passed with no new appointment, and he too, was absent from the National Day reception. This is out of the ordinary and suggests problems. Rumours of his involvement in corruption are not implausible, especially given his background in the aerospace and defence industry, where several senior figures have been purged in the past year.

One might ask: if the evidence strongly suggests that both men are “in trouble”, why would it be unlikely that their cases will be disclosed at the fourth plenum? After all, haven’t previous plenums addressed fallen officials?

Personnel changes only secondary

One might ask: if the evidence strongly suggests that both men are “in trouble”, why would it be unlikely that their cases will be disclosed at the fourth plenum? After all, haven’t previous plenums addressed fallen officials?

That is true — the seventh plenum of the 18th Central Committee confirmed the Politburo’s decision to expel Chongqing party secretary Sun Zhengcai; at the third plenum in July last year, the Central Committee accepted Minister of Foreign Affairs and State Councilor Qin Gang’s resignation and confirmed the Politburo’s decision to expel Minister of National Defence and State Councilor Li Shangfu from the party.

But here we must understand one key point: when plenums announce cases involving Central Committee members or alternates, those cases have already been publicly disclosed beforehand. The plenum’s role is simply to “rubber-stamp” the decisions, as required by party regulations — a procedural necessity. In other words, if an official’s downfall has not been announced before the plenum, their case will not appear on the plenum agenda.

As of now, He Weidong and Ma Xingrui have not been officially declared under investigation, nor has any disciplinary decision been announced. Hence, they are presumed innocent within the party’s framework, and the fourth plenum will not take up their cases. Even if, in the next few days, the authorities were to announce their downfall, a process of investigation and disciplinary review would still follow, and only afterwards would the matter be brought to a plenum for confirmation. In other words, even if they are “in trouble”, their cases would only appear on the agenda for next year’s fifth plenum at the earliest.

Therefore, the reasonable expectation for this fourth plenum is: no major personnel moves, and no discussion of He Weidong or Ma Xingrui. The personnel-related developments that may occur will be limited.

Meanwhile, there is the possibility of filling a vacancy in the Politburo.

Operational logic of CCP politics

For figures like senior military official Miao Hua and other Central Committee members or alternates whose cases have already been made public, the plenum may issue procedural confirmations, which would be reflected in the communiqué. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of filling a vacancy in the Politburo. Currently, the Politburo has 24 members, one fewer than the customary 25. If the leadership decides to restore the number to 25, the fourth plenum would be a likely occasion to add one.

The timing is appropriate: with two years left before the 21st Party Congress, waiting until the fifth plenum would leave only a year, which may be considered too late. But such an addition would be a “point adjustment”, not a structural shift, and would not qualify as a major personnel change.

In short, the fourth plenum will not be a personnel session but a policy session centred on the 15th Five-Year Plan. Unless there is a sudden political upheaval in the coming days, economic and social strategy will take centre stage, while personnel issues remain secondary. Those who fail to grasp this operational logic of CCP politics, and the political reality of Xi’s unchallenged power, and instead allow appearances to mislead them or project their own political imagination onto reality, will find it difficult to make accurate assessments of China’s political trajectory.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)