How Singapore’s ‘chief architect’ helped shape reform in China

When Singapore’s former deputy prime minister Goh Keng Swee became an adviser to China in the 1980s, he brought more than policy know-how — he helped shape its reform era. Caixin Global journalists tell us how Goh’s quiet influence has left a lasting mark on both nations.

(By Caixin journalists Li Xin and Wang Kerou)

In a quiet corner of Singapore’s eastern coast, an unassuming two-story house could easily be mistaken for any other. Step inside, though, and it unfolds like a miniature China museum. The rooms are filled with ink paintings, porcelain vases, hand-woven carpets, bronze horses and embroidery from every corner of the country — Jiangsu, Guangdong, Yunnan, Guizhou and beyond.

This was the home of Goh Keng Swee, Singapore’s late deputy prime minister and one of the chief architects of the island nation’s modern economy. Revered for his analytical rigour and deep pragmatism, Goh was instrumental in transforming a resource-scarce city-state into a global hub of trade and finance. But a lesser-known chapter of his life unfolded far from Singapore’s shores — in China, during one of the most pivotal moments in the country’s history.

In 1985, a year after his retirement, Goh received an invitation from Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader steering his country toward reform and opening. For the next five years, Goh served as an adviser to Beijing, offering counsel on the development of China’s coastal economic zones and its nascent tourism sector.

It was a critical period. China was poor, short on machinery, institutions, expertise and foreign currency. Goh’s experience in steering Singapore through industrialisation and opening to global markets proved invaluable. His influence — quiet as it was — helped shape the early economic frameworks of a country that would, within decades, rise to become the world’s second-largest economy.

When Goh died in May 2010 at the age of 91, tributes poured in from across Singapore and beyond. Wang Xiaolong, then chargé d’affaires of the Chinese Embassy, described him as “a sincere friend of the Chinese government and people”.

In a recent interview with Caixin, Goh’s wife, Dr. Phua Swee Liang, 86, spoke about those years of Goh’s advisory work to China. Sharp and spirited, she recalled her husband’s bond with Deng and his admiration for China’s determination to modernise.

“We in Singapore were fortunate to have a visionary economic practitioner who was never obsessed with material gains,” she said, “but who persevered through difficulties, committed always to improving the lives of ordinary Singaporeans.”

Deng in Singapore

In 1978, two years after the end of China’s decade-long Cultural Revolution, Deng embarked on a series of diplomatic missions. He travelled to Burma, Nepal, North Korea and Japan, before turning his attention to Southeast Asia — visiting Thailand, Malaysia, and finally, Singapore.

At the time, Singapore stood as a striking example of what discipline, pragmatism and openness could achieve. The island nation had already entered the ranks of middle-income economies, propelled by an export-oriented model built on labour-intensive industries. But its leaders were already looking ahead. The government was preparing a strategic shift toward technology-driven, capital-intensive growth.

As a small and resource-poor country, Singapore had harnessed foreign capital and multinational partnerships to transform its economic base. Goh, one of the key intellectual forces behind this transformation, had been the architect of the Economic Development Board (EDB) and the master planner of local industrial park that served as a magnet for global investment.

By the late 1970s, Singapore’s transformation was well underway. Under its Ten-Year Economic Development Plan for the years 1971 to 1980, the economy grew an average of 10% annually. Gross domestic product doubled to around US$10.5 billion, and foreign investment reached S$7.8 billion (US$6 billion). The economy diversified rapidly — manufacturing, transport and finance all expanded their share — and by the decade’s end, Singapore’s total trade had surpassed US$20 billion, the highest in Southeast Asia.

During one exchange, Deng turned to Lee with a question that revealed the urgency of his mission. “What do you think is the greatest obstacle to China’s reform today?” he asked. “Talent,” Lee replied without hesitation, gesturing toward the man beside him.

When Deng’s plane touched down in Singapore that November, China and Singapore had not yet established formal diplomatic ties. Even so, a quiet familiarity already existed. Two years earlier, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had been invited to Beijing, where he met with Mao Zedong.

In Singapore, Deng’s itinerary included a stop at Jurong, the country’s newest industrial hub — a creation deeply tied to Goh’s vision. Once a mosquito-ridden swamp on the island’s western fringe, Jurong had been transformed into a dense landscape of factories, warehouses and construction cranes.

Accompanied by Goh, then Singapore’s deputy prime minister, Deng toured the estate and planted a sea apple tree, a ceremonial gesture marking China’s budding industrial ambitions. A day later, meeting with representatives from Chinese institutions in Singapore, he reflected on what he had seen. “The path we are taking is the right one,” he said.

For Deng, the visit was more than symbolic. He had come to Singapore searching for ideas — and ways to turn those ideas into policy. Goh’s precision, discipline, and economic intellect made an immediate impression.

During one exchange, Deng turned to Lee with a question that revealed the urgency of his mission. “What do you think is the greatest obstacle to China’s reform today?” he asked.

“Talent,” Lee replied without hesitation, gesturing toward the man beside him. He cited Goh as an example of what visionary administrators could do for a country — men who could manage complexity, execute policy and raise living standards through disciplined pragmatism.

“Dr. Goh,” Lee said, “is very capable — and a man of action.”

Adviser to China

Goh’s path to becoming one of China’s earliest foreign advisers was, in many ways, shaped by the world’s shifting tides — and by his own disciplined intellect.

Born in 1918 in Malacca, Malaysia, to a family with ancestral roots in East China’s Fujian province, Goh grew up in a region that bridged multiple cultures and empires. In 1948, he left for London to study economics at the London School of Economics, where he absorbed not only theory but also the pragmatism that would define his later policymaking. When he returned to Singapore in 1951, he joined a circle of young idealists that included Lee, with whom he would go on to co-found the People’s Action Party.

When Britain granted Singapore self-rule in 1959, Goh became the country’s first Minister for Finance. His analytical rigour helped lay the foundations of Singapore’s fiscal discipline and industrial policy. After Singapore’s sudden separation from Malaysia in 1965, Goh was tasked with another formidable assignment: building a national defence system from nothing. As Minister for Defence, he designed the framework for National Service and the creation of the Singapore Armed Forces, institutions that remain central to the country’s identity today.

Over the next two decades, Goh would serve as deputy prime minister, overseeing Singapore’s economic strategy through its most transformative years.

In 1984, when Goh announced his retirement from Singaporean politics, Beijing moved swiftly. Deng sent a delegation led by Wu Xueqian, China’s foreign minister, to personally invite Goh to become an adviser on economic zones.

Impressed by Singapore’s success — and by Goh’s command of economic details — Deng extended an invitation for Goh to visit China. In 1979, Goh spent two weeks in China touring factories, research institutions and coastal cities. During a meeting in Beijing, Deng personally invited him to serve as an adviser to the State Council, China’s cabinet, once he retired from public office. Goh agreed.

That same year, in an interview with the Xinhua News Agency, Goh shared his candid assessment of China’s challenges.

The country’s modernisation, he said, would hinge on the development of a “contingent of high-caliber scientists, engineers and managers”, supported by strong institutions of higher learning. He also offered detailed suggestions for managing foreign exchange and building a sustainable tourism industry — areas where China was then taking its first experimental steps.

In 1984, when Goh announced his retirement from Singaporean politics, Beijing moved swiftly. Deng sent a delegation led by Wu Xueqian, China’s foreign minister, to personally invite Goh to become an adviser on economic zones.

According to Phua, Goh’s wife, what followed was a period of quiet diplomacy. That June, Goh made a discreet solo trip to Hong Kong, meeting several leading business figures — among them Robert Kuok, Li Ka-shing, and Run Run Shaw. From there, he flew to Beijing, where he met with Deng once more.

The details of their conversation remain unknown. But the timing was significant — the world was abuzz with news of the impending handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China. “I believe this meeting deepened Deng Xiaoping’s positive view of Dr. Goh Keng Swee’s economic policy capabilities,” Phua recalled in an interview with Caixin.

Soon after, the formal invitation arrived. “He accepted quickly,” Phua said. “I think in his mind, he was quite confident.”

Guided by his understanding of China’s needs, Goh brought with him three teams of Singaporean experts — one of bankers and economists, another of engineers, and a third of educators.

Three teams

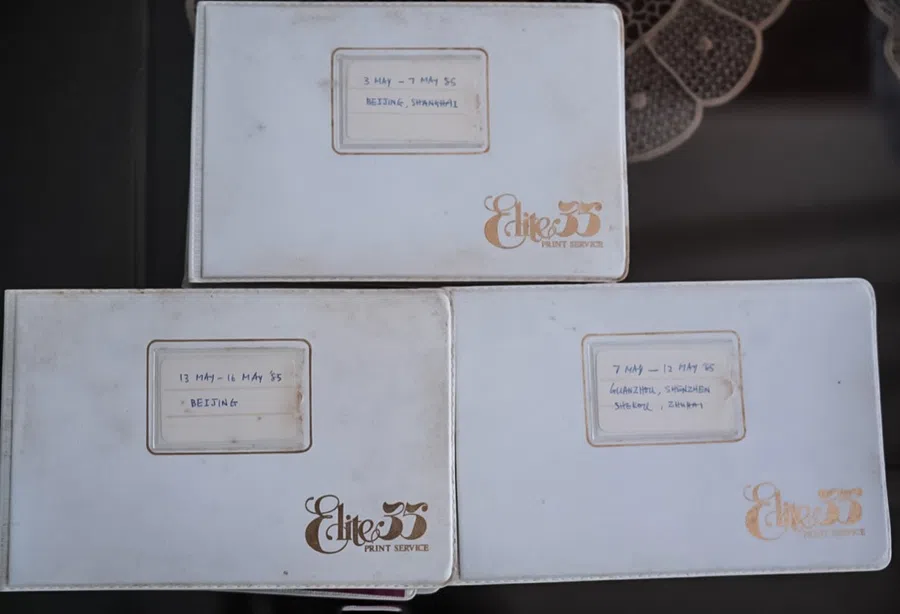

When Goh arrived in China in May 1985, it was not as a solitary adviser, but as the leader of a carefully assembled mission.

Guided by his understanding of China’s needs, Goh brought with him three teams of Singaporean experts — one of bankers and economists, another of engineers, and a third of educators. Each team represented a cornerstone of Singapore’s own success story: sound finance, disciplined infrastructure building, and an education system tied closely to economic development.

To minimise the risks of international travel — still less predictable then than now — the three groups travelled separately, converging later in Beijing. Among them was Phua, who had previously worked under Goh at Singapore’s Ministry of Education. They later married in 1991. Phua still remembers walking along Beijing’s broad streets, watching vendors sell fruit, cigarettes and trinkets from makeshift stalls. “I wondered, like many Chinese people then,” she said. “‘Is this communism or capitalism?’”

By the time Goh’s delegation arrived, Deng had already signalled the next phase of reform. In December 1984, he had toured China’s first Special Economic Zones (SEZs) — Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Xiamen — as well as the Baoshan Iron and Steel Works in Shanghai. Declaring the SEZ policy “feasible”, Deng’s endorsement helped pave the way for a sweeping decision the following May, when the Communist Party Central Committee and the State Council approved a plan to open 14 coastal port cities to foreign investment. The momentum was clear: China was opening to the world, but it needed to learn how.

When Deng met with Goh in Beijing, he framed the challenge in terms that were both urgent and philosophical. “Knowledge and talent are paramount in modernising China,” Deng told him. “Our greatest weakness lies precisely in this — insufficient knowledge and talent. We invite you to contribute knowledge. Not only you, but also retired experts and technicians from developed countries. We need them as consultants, even as full-time staff in our enterprises.”

It was an extraordinary moment — a revolutionary leader asking foreign economists for help in designing his nation’s economic foundations.

Over the next weeks, Goh and his team travelled through Shenzhen, Shekou, Zhuhai, Shanghai and Guangdong, before returning to Beijing. Everywhere they went, they found energy and uncertainty intertwined. Factories were rising from farmland, and yet the gaps in management, finance and training were obvious. On the flight back to Beijing, Goh wrote a report to Deng, his mind already working through the practical steps needed to turn policy into working systems.

Phua recalled one stop in particular — Shenzhen, then a raw, half-developed outpost on the border with Hong Kong. “It was mostly empty land, with scattered houses and dusty roads,” she said. “It reminded him of Singapore’s east coast in the 1960s, before development.”

Yet Goh saw what others could not. When they returned to Beijing, he gave Deng a prediction: “In 20 to 30 years,” he said, “China will be one of the world’s great economic powers.”

Instead of relying on import substitution — the strategy favoured by many developing countries at the time — China should invite foreign companies to set up factories inside its SEZs, producing for export and, in the process, transferring technology, managerial know-how, and industrial discipline to Chinese workers.

The Singapore experience

When Goh formally became China’s special economic adviser in 1985, he carried with him not only decades of experience but a conviction that China’s best path forward lied in adapting — not copying — the Singapore model.

His advice to Deng was simple in principle but radical in practice. China should pursue export-oriented industrialisation, open its doors to foreign capital, and use the resulting inflows of foreign exchange to build its industrial base. Instead of relying on import substitution — the strategy favoured by many developing countries at the time — China should invite foreign companies to set up factories inside its SEZs, producing for export and, in the process, transferring technology, managerial know-how, and industrial discipline to Chinese workers.

China was eager for such guidance. Alongside Goh, Beijing also invited a handful of other foreign economic experts, including former Japanese Foreign Minister Takeo Fukuda and German economist Armin Gutowski, most personally recruited by Vice Premier Gu Mu. Deng’s directive was clear: “The better we learn, the faster and better we will achieve our goals.”

Phua recalled that Goh had warm friendships with the Japanese experts, but he was firm in his own convictions. “He believed China should neither follow Japan’s global investment path nor adopt import substitution,” she said. “His advice was the opposite — to attract the world’s capital into China.”

Goh urged China to learn from Singapore’s development playbook: accumulate foreign exchange, channel it into industrial growth, and develop an export machine powered by skill and discipline. He also pressed Beijing to send large numbers of students abroad to study science, engineering and business — to learn from the world and bring that knowledge home. “He felt China would benefit greatly from this,” Phua said.

To Goh, China had every ingredient for success — talent, culture, history and natural resources — but it lacked one key asset: foreign exchange. It was a constraint that China had to break free of.

“He had spent 20 years making Singapore successful,” Phua recalled. “He used to say, ‘The Chinese are descendants of scholars and literati, while Singaporeans are descendants of coolies. If the Chinese work together, they’ll have a bright future.’”

A tourism adviser

Between 1985 and 1990, Goh travelled to China twice a year, each trip lasting one or two months. His delegation was small — just himself, Phua, and a civil servant from Singapore’s Ministry of Trade and Industry. His focus was the four special economic zones: Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou and Xiamen. After each visit, he would produce a detailed report for China’s State Council, filled with concrete policy recommendations.

Goh believed that tourism was not merely a leisure industry but a vital channel for earning foreign exchange. He proposed — and Beijing readily agreed — that he also serve as China’s tourism consultant.

At Zhongnanhai, the compound where China’s top leaders live and work, Goh met regularly with Deng and senior officials. Each meeting began with a briefing from Chinese ministries, summarising how they had implemented Goh’s previous suggestions. He also worked closely with Gu, then vice premier in charge of economic reform. When Goh passed away in 2010, Gu’s children sent Phua a faxed condolence letter “on behalf of all descendants of Gu Mu”.

During his field visits, Goh observed the teething pains of a country in transition. In many factories, he noted, “workers could not yet produce as they were instructed,” constrained by central planning systems. These observations led him to advocate deeper market-oriented reforms and to invite Chinese officials to visit Singapore for first-hand study.

Phua noticed that while the SEZs shared similar policies, their progress differed sharply — a reflection, she said, not just of geography but of leadership. “Li Hao, the party secretary and mayor of Shenzhen, was very pragmatic,” she recalled. “Every time I visited, I could see change. And look at Shenzhen now.”

For all his influence, Goh never accepted payment for his advisory work.

Some of Goh’s recommendations even influenced nearby Dongguan, which was not originally designated as a special zone. “At the time, there was no plan to develop Dongguan alongside Shenzhen,” Phua said. “But Dongguan succeeded anyway — officials used many of the ideas he proposed for Shenzhen.”

Goh also saw the darker side of rapid reform. “Some goods were scarce and required connections to obtain,” Phua remembered. “And as the economy accelerated, some people pursued personal gain — corruption appeared … even if corruption can never be eradicated, it can be controlled — as we do in Singapore.”

“At that time, people wanted openness, development and lower prices,” Phua said. “They needed a roadmap — and Dr. Goh helped provide one. But he never imposed. He offered ideas,” and only the Chinese themselves could shape their path.

Goh took particular interest in young Chinese technocrats who combined discipline with an international outlook. One of them was Zhou Xiaochuan, who would later become governor of the People’s Bank of China. “He invited Zhou to lunch once,” Phua recalled, “and was struck by how well Zhou understood the Western banking system — and how he was adapting it to Chinese realities.”

For all his influence, Goh never accepted payment for his advisory work. Zhang Qing, then deputy director-general at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, later wrote that Beijing had offered him US$60,000 per year, which Goh initially refused. When pressed to accept, he donated the entire sum to a local elementary school.

His frugality extended even to travel. “He insisted on flying with Chinese airlines,” Phua said. “He said China needed foreign exchange. It was a small thing, but it showed how frugal he was.”

Reflecting on those years, Phua said: “You know, back then, no one thought China would learn from Singapore. But it did. ... The relationship can actually provide inspiration for developing countries — even a country as vast as China can humbly learn from a small country like Singapore.”

Understanding China today

China and Singapore officially established diplomatic relations in 1990. Goh declined China’s invitation to continue serving as an economic advisor, citing age and declining health, though his interest in China never waned. That same year, he reorganised Singapore’s Institute of East Asian Philosophy, renaming it the Institute of East Asian Political Economy — the predecessor of today’s East Asian Institute, a think tank dedicated to studying East Asian policy, with China as a core focus.

In 1992, during his famous Southern Tour, Deng offered some words of praise for Singapore. “Singapore’s social order is good, and they have strict management. We should learn from their experience.”

When Goh heard this, he was deeply pleased.

To Phua, Deng and Goh were kindred spirits — pragmatic, incisive and united by a common conviction: that policy must serve to improve people’s lives. Both were willing to make bold decisions and replace those who erred in pursuit of the public good.

“Dr. Goh had great admiration for Deng Xiaoping,” Phua said. “Do you know what the biggest thing China and Singapore have in common?” she asked, before answering herself. “Policies must benefit the people.”

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Weekend Long Read: How Singapore’s ‘Chief Architect’ Helped Shape Reform in China”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.