‘Listeners under the bed’: Obsessing over secrets in Chinese elite politics

Academic Li Cheng and researcher Zhang Chi of the Centre on Contemporary China and the World in Hong Kong observe the workings of the rumour mill about China’s top leadership. In the year, this usually sees two peaks forming around the annual Two Sessions in early March and prior to or during the Beidaihe summer retreat in early August.

A seasoned scholar of Chinese subculture once observed, “Politics is salt for Beijingers. Without it, life would become tasteless.” The city has long played host to a classic tableau: middle-aged men, liquor-loosened, trading boasts and political gossip — “I know so-and-so who told me such-and-such,” or “Did you hear what happened between X and Y?” By morning, sobriety would erase their whispers, forgotten until the next round of drinks. Now, the ritual has migrated online.

Speculations about the echelons of top power

“Listening under the bed”, or ting chuang (听床), a phrase coined by China’s younger generation, captures this phenomenon of online political tall tales. Originating around the time of the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), it mocks those claiming insider knowledge of CCP leadership shuffles and factional struggles. These accounts often claim improbably granular details, evoking the image of eavesdroppers lurking beneath beds of leaders resting in Zhongnanhai.

These so-called “listeners under the bed” weave fabrications from completely false or partial truths that are largely misleading and disproven by subsequent events. However, despite their inaccuracies, these grown-up bedtime tales persist, circulating widely across digital platforms.

... it is natural that Xi is not travelling as frequently as he did ten years ago. Yet, since 2024, he has visited ten countries and 18 provincial jurisdictions.

A recent popular narrative speculates that China’s top leader is in descent and even foresees legitimacy crises for CCP rule. The claim connects “disparate dots”: President Xi Jinping’s reduced outbound travels, speculated devolution of the Central Committee’s decision-making and coordination institutions, and the absence of certain terminology in some official statements.

As a political norm, the Chinese government does not address these rumours, suspecting that refutation would only trigger the circulation of more speculations and theories. Many of these rumours can be invalidated easily. For example, judging a leader’s power based on the number of trips they take abroad is illogical. As a matter of fact, the number of foreign trips taken by Xi is far greater than any of his predecessors. Considering geopolitical factors and age, it is natural that Xi is not travelling as frequently as he did ten years ago. Yet, since 2024, he has visited ten countries and 18 provincial jurisdictions.

Significant personnel changes are ongoing and have been so for many years. They should not come as a surprise, given the high value that Xi has placed on official accountability and never-ending anti-corruption drives.

Additionally, the alarmist predictions of the collapse of CCP rule are baseless. According to the Central Organisation Department’s newest records, its membership now exceeds 100 million, with the proportion of college degree holders increasing from 56.2% (Dec 2023) to 57.6% (June 2025), including a majority of graduate students at some top universities. As geopolitical competition has intensified — and when many perceive the US as aiming to firmly contain China’s rise — the Chinese public often becomes more supportive of its leaders.

Feeding the rumour mill

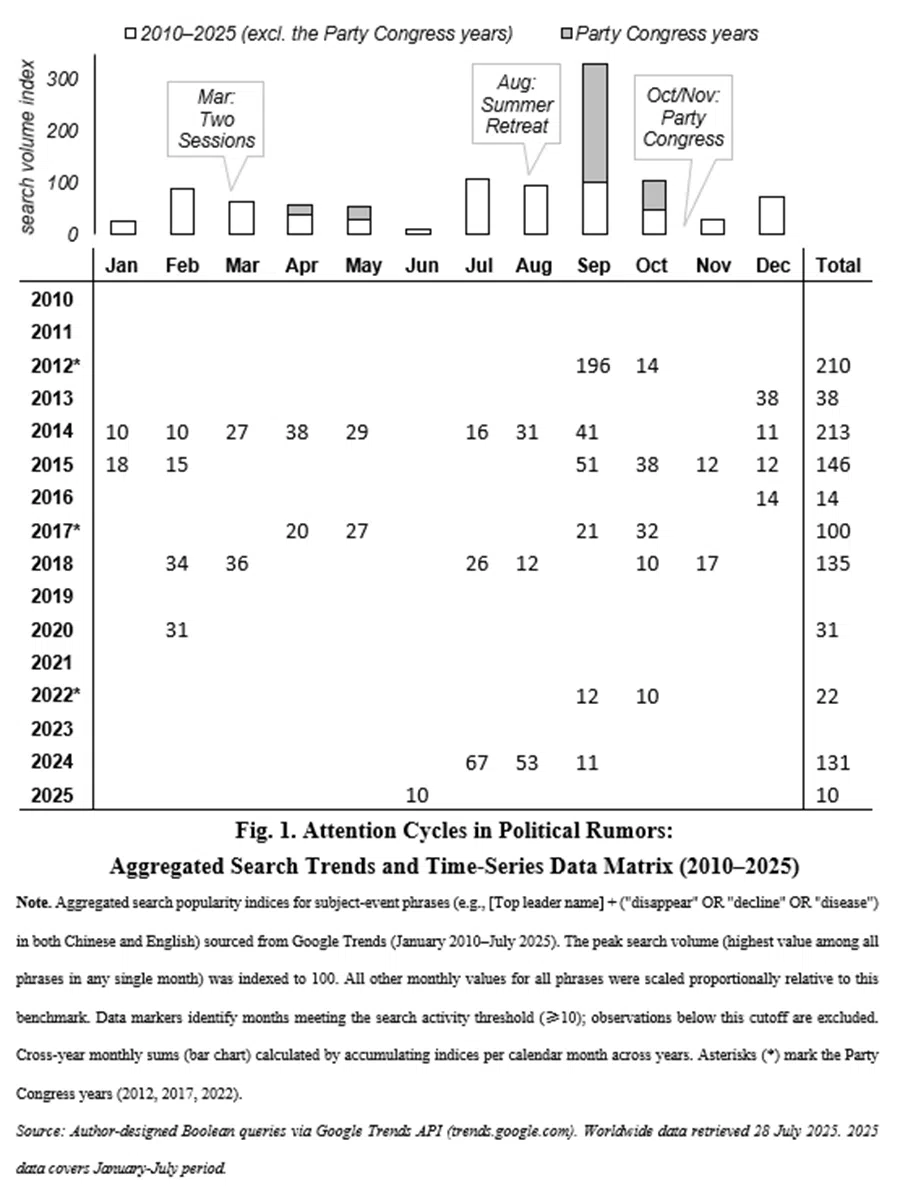

The prevalence of these rumours is nothing new. Our aggregated Google Trends analysis on frequency indices for subject (President Xi) and speculation phases (e.g. “disappear”, “disease”, and “decline” in both Chinese and English) from the past 15 years (Fig. 1) reveals three patterns: First, similar rumours have been prevalent in 58.3% of months since 2010, only differing in scale and specificity.

Predictably, the quinquennial Party Congress years see additional spikes. More public exposure, like state visits, can also drive interest. For example, Xi took 35 foreign trips in 2014-2015 (nearly one-third to the West), with his September 2015 US visit producing one of the highest peaks. Conversely, the Covid-19 pandemic suppressed searches from March 2020-April 2022, marking the most pronounced lull.

This recent surge, starting around June 2025, reveals two new developments: it is reaching beyond its usual circles — being noticed by outsiders and experts rather than just political enthusiasts — and crossing linguistic barriers...

Second, within each year, two peaks form around the annual Two Sessions in early March and prior to or during the Beidaihe summer retreat in early August. During Party Congress years, an additional peak occurs in September and October, especially at the ten-year generational transition in various leadership bodies, which are typically the highest of the year. When these factors overlap, rumours tend to surge and gain extra attention.

For instance, after the 2012 summer retreat and ahead of the 17th Party Congress, rumours went viral that Xi’s prolonged “disappearance” and mobility issues signalled assassination attempts, distorting his back sprain from swimming into a coup plot or other false speculations reflecting an incredibly poor understanding of Chinese elite politics.

Third, following the pandemic lull, a new wave of rumours has begun to rise. This recent surge, starting around June 2025, reveals two new developments: it is reaching beyond its usual circles — being noticed by outsiders and experts rather than just political enthusiasts — and crossing linguistic barriers, originating from the Chinese-speaking world and later covered by mainstream English-language media. As the 21st National Congress approaches, these rumours are expected to grow over the next two years.

Within the House Select Committee on the CCP, inexperience with Beijing is touted as an asset...

Why are these rumours so prevalent? There are three deeper reasons that have contributed to and may intensify the spread of misinformation and misinterpretation of Chinese elite politics.

Chinese characteristics and challenges

China’s raised profile and increased assertiveness on the global stage has compelled formerly uninterested observers to engage with Chinese politics. Moreover, travel disruptions beginning at the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the reduction of foreign journalists in China and rising geopolitical tensions have added layers of complexity to understanding China’s opaque political landscape. Also, one of the enduring fascinations with Pekingology is the art of reading between the lines; a limited civil society and strict restrictions like the Overseas NGO Law have created fertile ground for mystification.

China Studies in the West are declining

Western capitals, particularly Washington, DC, have devalued their China experience over the past decade. Within the House Select Committee on the CCP, inexperience with Beijing is touted as an asset; after recent large-scale layoffs, the White House National Security Council and the State Department no longer know how many staff speak Mandarin; and young China watchers may hesitate to study in the mainland. This, in turn, makes the US more susceptible to rumours.

But the stakes are very high, and getting China and its leadership right is critically important. For Beijing, explaining governance mechanisms and promoting public accountability are essential for facilitating its global communications.

Digital frenzy and deepfakes

Streaming media has transformed “listening under the bed” and rumour-mongering into an even more lucrative industry. In this ecosystem, click-driven metrics are the sole engine of entropy. Online influencers cast themselves as modern Sherlocks, guiding fans with strong confirmation bias to cherry-pick favourable evidence, dismiss contradictions, reinforce preconceptions, and spin a cocoon of instant gratification. AI will further slash the costs of generating falsehoods while amplifying their impact, echoing Mao’s famous remark: “The use of fictions for anti-Party activity is a great invention.”

For the foreseeable future, rumours regarding Chinese elite politics are not going anywhere. But the stakes are very high, and getting China and its leadership right is critically important. For Beijing, explaining governance mechanisms and promoting public accountability are essential for facilitating its global communications. For Washington, DC and foreign countries, the knowledge of China must be revitalised to restore data gathering and verification capabilities. For scholars and China observers, “listeners under the bed” stand as a cautionary reminder to avoid the trap of hearsay. True insight demands more fact-oriented methodology, critical thinking and understanding of perspectives across social strata, sharpening the ability to discern signals from noise.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)