[Big read] China’s 10 trillion RMB debt clean-up falls short

China launched a massive 10 trillion RMB debt-resolution campaign in November 2024 to rescue cash-strapped local governments, but hidden liabilities dwarf official estimates. With land finance collapsing and LGFVs under strain, Beijing now faces pressure for a systemic fiscal overhaul. Lianhe Zaobao’s Chen Jing speaks with academics to assess China’s strategy.

As 2025 nears its end, China’s economy is still grappling with persistent deflationary pressures and a deepening slowdown in investment. The latest data highlight how sharply momentum has weakened.

Plunging numbers

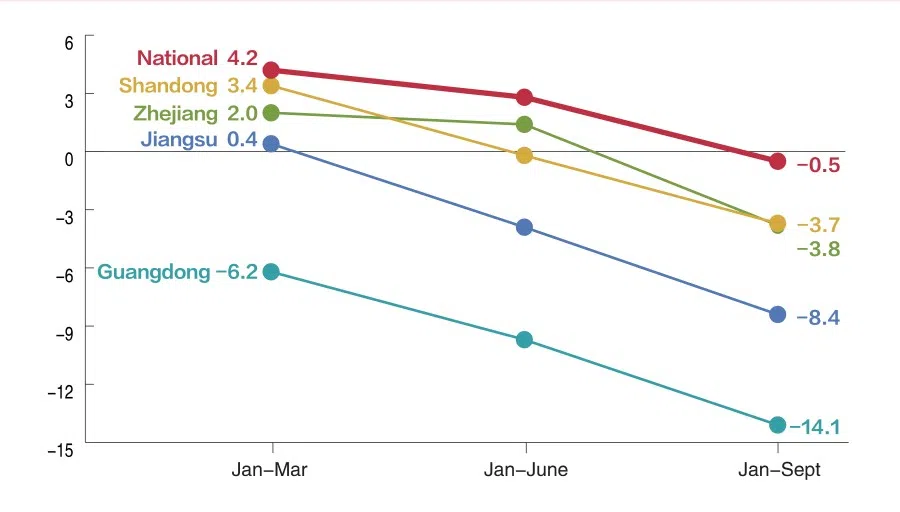

In September, fixed-asset investment recorded a steep year-on-year drop of 6.5%, the largest decline in almost five years. Over the first three quarters, fixed-asset investment slipped 0.5%, marking its first negative reading since October 2020.

The downward trend has continued. According to figures released on 14 November, fixed-asset investment from January to October contracted 1.7% compared with the same period last year. Independent estimates paint an even starker picture, suggesting that monthly growth in October may have plunged to –12.2%.

Altogether, the data point to a broad and worsening investment slowdown — one that is increasingly weighing on China’s overall economic outlook.

Guangdong, China’s largest provincial economy, saw investment plunge by as much as 14.1% in the same period.

Among the four provinces with the highest GDP — Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong and Zhejiang — the drop in fixed-asset investment during the first three quarters all exceeded the national average. Guangdong, China’s largest provincial economy, saw investment plunge by as much as 14.1% in the same period.

Besides being weighed down by persistently weak real estate investment, another major cause of the investment slowdown can be traced back to the 10 trillion RMB (US$1.4 trillion) debt restructuring plan introduced a year ago.

The 10 trillion RMB debt relief

In November last year, the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress approved 10 trillion RMB of resources for debt resolution. These include an annual debt quota of 2 trillion RMB from 2024 to 2026 to swap local governments’ existing hidden debts, as well as a yearly allocation of 800 billion RMB from newly issued local government special bonds from 2024 to 2028, earmarked specifically for debt reduction.

This package of debt-resolution measures is designed to ease the heavy debt burden on local governments. Unlike most major economies, public debt in China is borne largely not by the central government but by local governments. According to data from China’s Ministry of Finance, by the end of 2024, local government debt accounted for as much as 63% of total government debt, significantly higher than the central government’s 37%.

The surge in local government debt has several roots. Pandemic-control efforts drove up spending sharply over the three years of Covid-19, while slower economic growth and the collapse of the property market eroded fiscal revenue. Together, these pressures created a towering debt burden.

The fallout has been felt widely. Many local governments have accumulated long-term arrears to small and medium-sized enterprises, pared back public services and imposed salary cuts — or even delayed payments — for civil servants.

However, estimates from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggest that China’s hidden local government debt may have reached 60 trillion RMB by the end of 2023 — an amount equal to 47.6% of the country’s GDP.

Hidden debt — most prominently represented by the bonds issued by local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) — is the core pain point of local government debt. Hidden debt refers to debts incurred by local governments through financing platforms such as LGFVs (often government-owned companies created to borrow and invest on behalf of local governments), in addition to statutory debt.

According to official statistics, as of the end of last year, local hidden debt totalled 10.5 trillion RMB. However, estimates from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggest that China’s hidden local government debt may have reached 60 trillion RMB by the end of 2023 — an amount equal to 47.6% of the country’s GDP.

Debt swaps rise as LGFV financing tightens

Public data shows that in the first 10 months of this year, Chinese local governments issued more than 9.1 trillion RMB in bonds, a year-on-year increase of about 23%, the highest level ever recorded for the same period.

Based on these figures, Yicai estimates that of the 9.1 trillion RMB in government bonds issued, roughly 40% went toward project investment, while the remaining 60% was used to repay existing debt. Of the 5.65 trillion RMB allocated for debt repayment, 4.4 trillion RMB came from refinancing bonds — a 58% year-on-year increase — and 1.25 trillion RMB from newly issued special-purpose bonds.

By issuing these bonds, local governments can convert hidden or implicit debt into transparent, explicit debt at lower interest rates. This reduces their borrowing costs and helps ease short-term repayment pressures. Fitch Ratings estimates that through debt swaps, local governments could save a cumulative 1.08 trillion RMB in interest payments between 2024 and 2028.

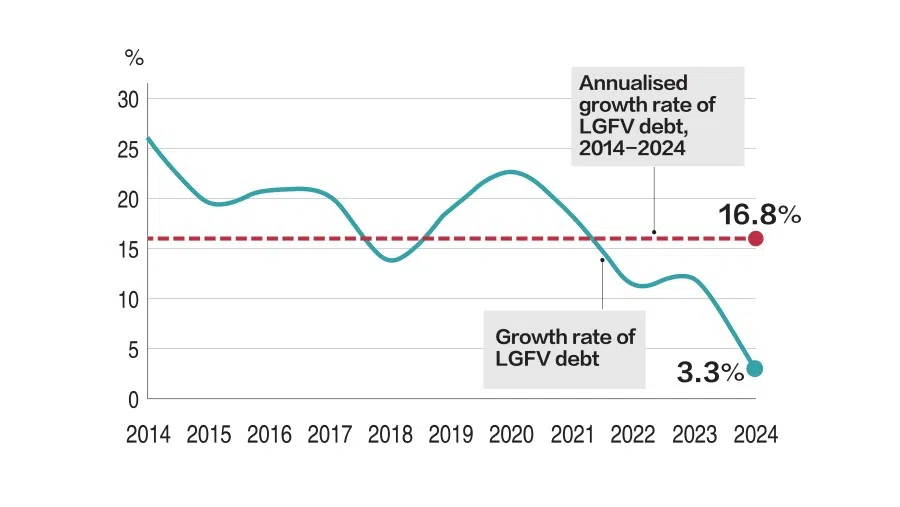

To curb hidden debt, authorities have since tightened regulatory oversight of LGFV bond financing.

To curb hidden debt, authorities have since tightened regulatory oversight of LGFV bond financing. Most LGFVs are now permitted to issue bonds only to refinance maturing obligations, while borrowing for working capital or new investment has been sharply curtailed. As a result, net LGFV bond issuance has collapsed — from nearly 1.4 trillion RMB in 2023 to just 152 billion RMB in 2024.

According to Fitch, after the rollout of the 10 trillion RMB debt-swap plan, the growth rate of nationwide LGFV debt in 2024 plunged to a historic low of 3.3%, far below the annualised 16% growth rate seen in the previous decade. Davis Sun, Fitch Ratings’ Senior Director for International Public Finance, told Lianhe Zaobao that unless there is unexpectedly large fiscal stimulus, LGFV debt growth will remain in the low single digits this year.

Over half of hidden debt already addressed?

In July, Inner Mongolia officially announced that it had exited the list of provinces under close scrutiny for local government debt, bringing the number of high-risk provinces and municipalities designated by the central government down from 12 to 11. At the end of October, People’s Bank of China Governor Pan Gongsheng reported that, by the end of September 2025, the number of LGFVs nationwide and the stock of their operational financial debt had dropped by 71% and 62%, respectively, compared with March 2023 — clear signs that risks have been significantly mitigated.

According to the research team led by Sun Binbin, chief economist at Caitong Securities, the amount of debt-resolution funds already implemented now covers more than 50% of the hidden or implicit debt that needs to be resolved before 2028. This suggests that local governments are more than halfway through the process of unwinding their hidden debt.

The 10 trillion RMB quota covers only 30% of this shortfall, meaning that a remaining gap of 24 trillion RMB cannot be addressed by the current debt-restructuring round... — Davis Sun, Senior Director for International Public Finance, Fitch Ratings

However, Davis Sun noted that as of the end of 2024, all LGFVs combined faced a debt gap of about 34 trillion RMB. The 10 trillion RMB quota covers only 30% of this shortfall, meaning that a remaining gap of 24 trillion RMB cannot be addressed by the current debt-restructuring round, and will still need to be filled through refinancing or government support.

Debt clean-up drags down investment

The debt resolution measures have produced immediate results, but their side effects cannot be ignored. According to the team led by Zhao Wei, chief economist at Shenwan Hongyuan Securities, the accelerated pace of debt resolution since mid-year has crowded out funds for investment, becoming the main reason for the downturn in investment.

Zhao’s team wrote that since June, the issuance of special refinancing bonds has exceeded 1.2 trillion RMB. Beyond the allocated quota of 800 billion RMB, an additional 400 billion RMB of new special-purpose bond quotas has been consumed, reducing the funds available for government investment. This has dragged down investment growth by more than three percentage points, with eastern regions — where special refinancing bond issuance has been particularly large — seeing even steeper declines in investment.

Secondly, policies this year have sped up efforts to clear unpaid bills owed by central SOEs and local SOEs. Given the current weakness in corporate profitability, funds that companies might otherwise have allocated for investment are instead being used to repay outstanding liabilities, contributing to the drop in fixed investment.

Fitch has also observed that tighter debt controls have significantly slowed the pace of LGFV asset expansion. The nationwide weighted average asset growth of LGFVs dropped sharply from 16.3% in 2020 to 6.3% in 2024, with the 12 high-risk provinces and municipalities recording growth of only 3%.

China’s Ministry of Finance launched a Debt Management Department.

Strengthening central debt management

Can risk control and growth promotion be balanced? Recent moves in Beijing have sparked public discussion about China’s debt-resolution strategy for the next five years.

In a late-November commentary on the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030), Finance Minister Lan Fo’an stressed strict prevention of new hidden debt, the need for a unified long-term local debt framework and the reform of local government financing platforms, while reaffirming the principle of “debt relief amid development”.

On 3 November, China’s Ministry of Finance launched a Debt Management Department. Its main responsibilities include setting and implementing government debt policies, drafting rules for central and local debt, allocating debt quotas and strengthening monitoring to prevent and mitigate hidden debt risks.

Caijing magazine noted that government debt management was previously scattered across multiple departments within the Ministry of Finance. Consolidating central, local and external debt under a single department will improve coordination of fiscal policy and debt instruments, supporting economic stabilisation and enabling more systematic debt resolution.

Yicai, citing Yuan Haixia, director of the China Chengxin International Research Institute, noted that China’s central government debt — in scale, share and leverage ratio — is much lower than local government debt and far below levels in major economies like the US and Japan. In a context of weak macroeconomic returns and low investment payoffs, increasing central government borrowing could boost effective demand and reduce the overall cost of public debt. Going forward, a larger share of newly added leverage may be shifted toward the central government.

In 1994, under the leadership of then-Vice-Premier Zhu Rongji, China launched the tax-sharing reform, under which 75% of value-added tax (VAT) revenue was allocated to the central government and consumption tax revenue was fully centralised.

Central control and local needs: time for tax reform?

Shen Meng, executive director of Xiangsong Capital, said that to break the impasse of local government debt, China must address the root cause of local governments’ chronic fiscal shortfalls: declining revenue capacity. This means the tax-sharing system implemented more than 30 years ago must be reformed.

In 1994, under the leadership of then-Vice-Premier Zhu Rongji, China launched the tax-sharing reform, under which 75% of value-added tax (VAT) revenue was allocated to the central government and consumption tax revenue was fully centralised. At the same time, separate national and local tax administrations were established.

This reform quickly reversed the situation of “a weak central government and strong local governments” (弱中央、强地方), easing the central fiscal crisis of the time. But it also created a long-lasting pattern in which local governments were left with “too many responsibilities and too little money”. To supplement their limited revenues, local governments turned to land sales, giving rise to the era of “land finance”, which has become unsustainable following the collapse of the property market in recent years.

Shen noted that when the tax-sharing system was introduced, the central government’s finances were relatively weak. “Thirty years later, China is the world’s second-largest economy. It is time to adjust the system and explore granting local governments greater fiscal power commensurate with their administrative responsibilities.”

Professor Jean Oi, the Goh Keng Swee Professor in China Studies at the East Asian Institute (EAI) of the National University of Singapore (NUS), also said that reforming the current fiscal and tax system is imperative.

Professor Oi noted that after the collapse of land-based finance, local governments must find more institutionalised and sustainable sources of revenue. “A lot of work done by local governments was fuelled by debt. ... They should have a more institutionalised, dependable source of tax revenue that they can use to pay for the expenditure that they have been assigned… this is really the only long-term solution to the local debt problem.”

LGFVs: elimination or transformation?

To curb hidden debt, Beijing has decided to eliminate its primary borrowing vehicles: local government financing platforms (LGFPs), represented by LGFVs.

In July 2025, the Communist Party of China’s Politburo proposed for the first time to “vigorously and effectively promote the orderly liquidation of local financing platforms”. One month later, the People’s Bank of China and three other central agencies issued a joint notice calling for the elimination of LGFPs, the eradication of hidden debt, the removal of LGFVs from the list of financing platforms and the stripping of governments’ investment and financing roles by June 2027.

Following the introduction of this policy, LGFVs across China have accelerated their exit as financing platforms. According to research by Founder Securities, as of 26 September, 114 LGFVs had announced their exit this year. Finance Minister Lan Fo’an revealed that the number of LGFPs decreased by over 7,000 in 2024; by the end of June this year, more than 60% had already exited.

However, Professor Oi’s research reveals that instead of shutting down completely, many LGFVs choose to transform themselves into investment companies and continue operating. Whether such transformations can succeed has become a key factor for both local debt resolution and economic growth.

Statistics show that as of 2023, there were about 18,000 LGFVs in China. For two to three decades, these entities were the main vehicles responsible for financing local government investment projects. They became hubs for public resources — capital, land and equity — while also being hotspots for financial risks, including illegal guarantees, unauthorised borrowing, and inappropriate leveraged investments.

... economically developed regions such as Hefei in Anhui and Hangzhou in Zhejiang are able to inject higher-quality resources into their LGFVs, making transformation relatively easier. — Professor Jean Oi, Goh Keng Swee Professor in China Studies, East Asian Institute

Professor Oi noted that in recent years, local governments have tried to enhance the credibility of LGFVs through structural reforms and resource reallocation, making them more appealing to investors. “While local governments once relied heavily on land finance, transforming LGFVs could now provide more diverse and systematic revenue sources,” she said.

However, Professor Oi pointed out that the success of such transformations depends on multiple factors, noting that economically developed regions such as Hefei in Anhui and Hangzhou in Zhejiang are able to inject higher-quality resources into their LGFVs, making transformation relatively easier. In contrast, although the prefecture-level city of Zunyi in Guizhou province is home to the famed Moutai liquor, the Kweichow Moutai Co. Ltd is managed at the provincial level, leaving the local government with limited resources to support its LGFVs.

At the end of 2022, Zunyi’s largest LGFV — Zunyi Road & Bridge Construction Group, wholly owned by the Zunyi State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission — announced that its 15.6 billion RMB in bank loans would be extended over 20 years, with interest-only repayments for the first ten years and no principal repayment. This unprecedented restructuring shocked the market and highlighted the severe fiscal distress faced by some local governments.

Caixin reported last month that some LGFV “transformations” are largely cosmetic, with operations remaining much the same. Even LGFVs that successfully develop new business models face greater compliance scrutiny, making it harder to secure fresh financing due to their LGFV origins.

Fitch Ratings’ Davis Sun believes that genuine independent debt-servicing ability is the gold standard for evaluating the success of LGFV transformation. In an environment where the macroeconomy faces multiple pressures and uncertainties, the return on assets (ROA) of LGFVs has been on a declining trend in recent years, indicating that further expansion of debt and assets may yield diminishing returns.

“The deeper challenge of LGFV transformation lies in whether it has a professional investment and operations team and an incentive structure that, while fulfilling its policy functions, can generate financial returns to cover its debt obligations.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “中央化债10万亿元一年后 中国多地政府面临稳增长与投资失速压力”.