[Photos] An assassination and an unexpected child: A Taiwanese journalist in the Philippines

From the assassination of senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr to the story of a woman named Gloria, who gave birth to a child with a Taiwanese fisherman on a remote island, former Taiwanese journalist and historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao recalls two defining moments from his time covering the Philippines. Through his lens, he reflects on how legends emerge from both significant and humble lives, revealing the intricate tapestry of geopolitics, history and human warmth that connects them all.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

The recent rift between President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr and Vice-President Sara Duterte has led to political instability in the Philippines, drawing international attention. The Philippines was in fact the very first country I covered as a journalist, and it left a deep impression on me. The first news story I covered was the assassination of Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr, who was shot upon arrival at Manila Airport from Taipei in 1983.

Aquino’s mysterious assassination

On 21 August 1983, Aquino, leader of the opposition, boarded a China Airlines flight in Taipei, leaving the final images of him as he cleared immigration at Chiang Kai-shek International Airport (today’s Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport). Immediately after disembarking from the plane in the Philippines, he was shot dead, leading to major political upheaval in the Philippines and sparking the People Power Revolution more than three years later, which saw millions take to the streets.

I have a photo from 1986, when I was posted to the Philippines as the Southeast Asia correspondent for the China Times. An American television journalist had followed Aquino and filmed him passing through Chiang Kai-shek Airport. I later visited their office in Manila and took a still image from their videotape — a valuable piece of footage I acquired.

At that time, the hotel staff did not yet have their antennae up, and revealed which room Aquino had stayed in and the name he registered under — I recall he used the alias Marcial Bonifacio.

On the fateful day of the assassination, I was a rookie foreign affairs reporter for the China Times just two months in. A young female colleague from the Associated Press said that a Filipino opposition leader was ending his exile in the US; he had stopped in Taiwan and was staying at the Grand Hotel in Taipei, and was scheduled to fly back to the Philippines that day, accompanied by a large group of foreign journalists. At the time, despite being aware of the news, I didn’t fully grasp its significance.

When I got to the office, I checked the wire services. Even as a rookie in the news industry, I could sense this was big. I immediately informed our news editor, Wang Chien-chuang, who took it very seriously. I quickly called the Grand Hotel. At that time, the hotel staff did not yet have their antennae up, and revealed which room Aquino had stayed in and the name he registered under — I recall he used the alias Marcial Bonifacio.

Andrés Bonifacio fought against Spanish colonial rule, and Fort Bonifacio was the military camp where Aquino was imprisoned. Marcial refers to martial law, symbolising Aquino’s life. With the information I gathered, I wrote the story. The next day, every other newspaper ran similar reports based on foreign wires. But China Times gave my story much more prominence, as it was an impressive exclusive that even identified Aquino’s hotel room and the alias he used.

My only regret is that I should have rushed to Chiang Kai-shek Airport to cover Aquino, but I was just a rookie who did not respond fast enough.

Looking back, here is my take of two mysteries behind the incident.

Who killed Aquino?

In 1972, President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, and Senator Aquino was arrested and sentenced to death. In 1980, following intervention by the US government, Aquino went into exile in the US. By 1983, President Marcos agreed to allow Aquino to return to the Philippines and guaranteed his safety. This was major international news, and a group of international journalists followed Aquino from the US to Taipei, and then from Taipei back to Manila — this was what I knew at the time.

Why didn’t any of the reporters who were following Aquino witness the shooting or take any photos? The reason is simple: as soon as the plane landed, the Philippine military boarded and took only Aquino away, blocking everyone else, including the journalists. Once Aquino was escorted off the aircraft, he was shot in the back of the head and died instantly. Naturally, those still in the plane could not see and were unsure of what had happened; a television journalist later managed to film through a plane window Aquino’s body lying on the tarmac.

I think they dared not investigate because it was not the act of a lone soldier. The military’s involvement was too deep and extensive, and an in-depth investigation would have caused chaos within the military.

That an opposition leader was gunned down in broad daylight drew international criticism. The killer was a Philippine soldier, but who? There was no answer when Aquino’s widow Corazon Aquino became president, or even when his son Benigno Aquino III became president 27 years after the shooting. The military never established a formal investigation committee. I think they dared not investigate because it was not the act of a lone soldier. The military’s involvement was too deep and extensive, and an in-depth investigation would have caused chaos within the military. Corazon Aquino’s presidency saw a frightening nine failed coup attempts, and there was no further investigation into the assassination, which became a mystery for the ages.

What was Aquino doing in Taiwan?

There are various claims online about Aquino’s movements in Taiwan. One sensational theory is that then Chief of the General Staff Hau Pei-tsun leaked Aquino’s whereabouts to the Philippine government, causing his death. Such a claim only looks and sounds convincing. At the time, Hau was in charge of military affairs, not foreign affairs or intelligence, and he would not have dared to act on his own under President Chiang Ching-kuo.

Besides, this makes it sound like Aquino’s movements were “secret”. From the time Aquino took off from the US, he had a whole bunch of journalists in tow, and his itinerary was public. Even a two-month rookie like me heard that he was in Taiwan and knew that he would be flying to the Philippines. If even I knew, what secrecy was there to speak of? Was a “leak” necessary?

... the Philippine government was tracking Aquino’s movements from the time he left the US. By the time he boarded the plane in Taipei, Philippine military personnel were already waiting for him at Manila Airport. So, the claim that Hau tipped off the Philippine authorities is all just nonsense.

I believe the fact is the Philippine government was tracking Aquino’s movements from the time he left the US. By the time he boarded the plane in Taipei, Philippine military personnel were already waiting for him at Manila Airport. So, the claim that Hau tipped off the Philippine authorities is all just nonsense.

Looking back, I believe that Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and intelligence agencies had absolutely no idea what was going on. After the newspaper ran Aquino’s room number and alias, someone later reached out to me through a friend to ask how I knew. This showed that the local authorities knew nothing of the incident, and had little clue who he was.

There’s also a little postscript to this story. The Filipino female television journalist who had accompanied Aquino on his return flight from Taiwan to the Philippines — the one who later let me take a shot of the precious footage — ended up five years later accompanying Imelda Marcos back from the US to the Philippines. Imelda was preparing to run for president, and the journalist became one of Imelda’s official spokespersons. It was utterly surreal.

The Philippines went through four centuries of Spanish rule, and even now its names and language feature many Spanish words, while traces of Spanish colonialism remain in the social structure and buildings in rural areas. It is really like Latin America, which is why its politics and society carries a sense of magical realism.

I heard a story — one should say a legend — at the Taiwan Representative Office (TRO), that Taiwanese fishermen had landed on a small island north of Palawan, married and had children with the local women, and so was formed a Taiwanese village.

A remote island, a mysterious Taiwanese village

Another story is of a mysterious Taiwanese village on one of the Philippines’ remote islands. In 1984, while I was on assignment in the Philippines, I heard a story — one should say a legend — at the Taiwan Representative Office (TRO), that Taiwanese fishermen had landed on a small island north of Palawan, married and had children with the local women, and so was formed a Taiwanese village.

I was fascinated by the legend. My head was filled with images of a beautiful island, blue waters, the next generation of Taiwanese settlers — a paradise on earth.

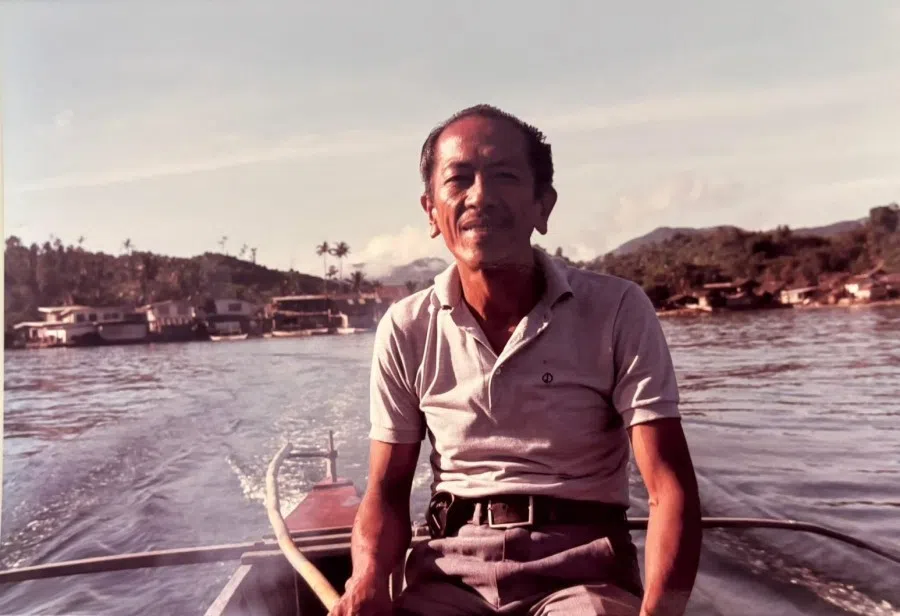

I couldn’t resist seeking the truth. Someone at the TRO later confirmed the approximate location on Linapacan Island, north of Palawan. To get there, I had to first fly to Puerto Princesa, the capital of Palawan, then weave through several islands.

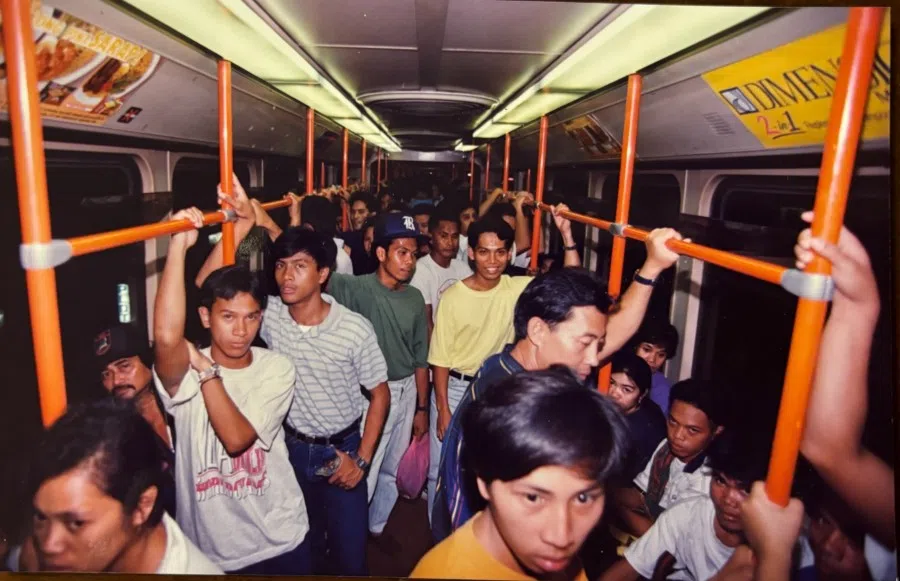

The little boat stirred up waves as it moved slowly through the night, the islands on both sides like ancient beasts slumbering, yet with eyes on the boat while it passed in the dark. The sea breeze was blowing as I lay back and gazed at the clear starry sky, each star sparkling and flawless, the Milky Way like a collection of little pearls stretching across the heavens. For the first time, the sea and islands of the Philippines made me feel like I was in a dream fantasy, marvelling at poetic beauty.

After three full days of navigating through the islands, I finally arrived at Linapacan Island in the north and unveiled the mystery of the “Taiwanese village”. The truth was very simple. It was a small village, and with a few inquiries, I quickly found the person involved — a Filipino woman named Gloria, who had a child with a Taiwanese boat captain. She carried the child and smiled as she said, “Taiwanese!”

The greatest reward was the soulful journey through the islands into the heart of the Philippines — deep, emotional and peaceful. That will stay with me for life.

Taiwanese fishing boats frequently operated in the waters around this area. They often landed on the islands to replenish fresh water and food supplies, sometimes even staying for a few days. There was one case of a captain having a child with a local woman, but as word spread, it became increasingly exaggerated into a “Taiwanese village” with dozens of households and heaps of children, showing how far legend was from reality.

Nevertheless, having taken so much effort to cross the ocean to reach this remote village and seeing a Filipino woman holding her Taiwanese child, I did not feel disappointed, but warm inside. The greatest reward was the soulful journey through the islands into the heart of the Philippines — deep, emotional and peaceful. That will stay with me for life.

Win-win for locals and fishermen

But there was a very real issue here. Taiwanese fishermen were landing on Philippine islands without any visas, which was clearly illegal. So why did local authorities turn a blind eye? Not only did they permit the Taiwanese to fish in nearby waters, they even allowed them to land illegally. Why?

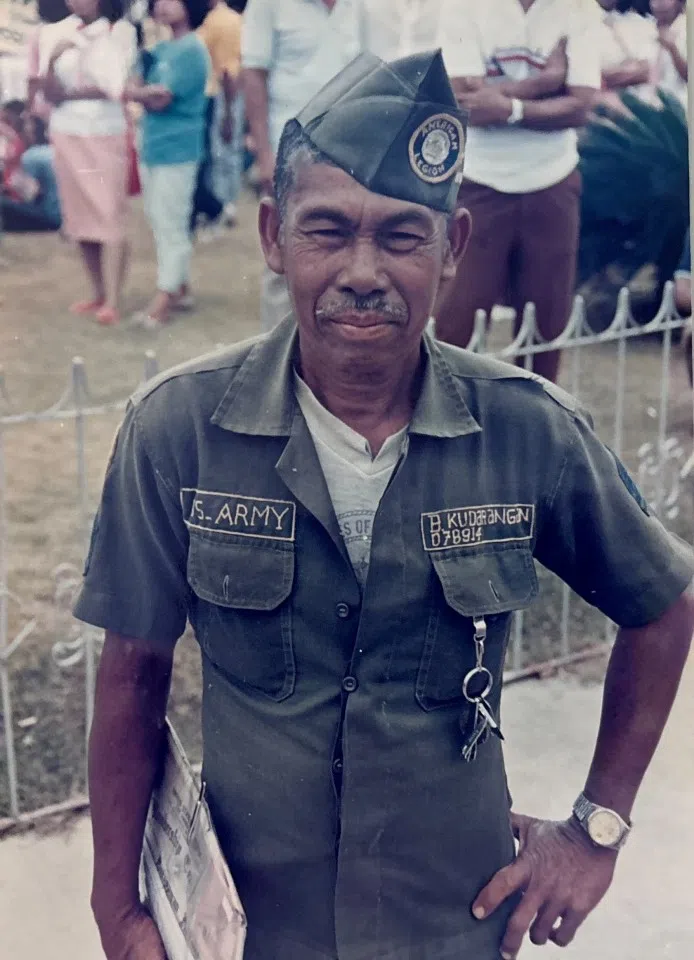

The village chief told me frankly, “The main reason is that they provide jobs and give us locals some income.” In other words, although the Taiwanese fishing boats were operating illegally in nearby waters, they would land and hire local people to work on board and pay them wages, increasing the community’s income. The village chief did not arrest them, but gave appropriate assistance, allowing them to stay on the island for a few days, during which some even started families with local women.

This led me to a further inference. The Philippine coastline was a key fishing ground at that time, with no large-scale inshore or deep-sea fishing fleets, and no issue of overfishing, so that fish stocks were abundant and attractive. Besides, the Philippines had no strong maritime defence force, while its islands were scattered and enforcement was loose. Many Taiwanese fishing vessels operated illegally in these waters and even collaborated with local officials to hire locals to work on the boats.

So, this was an “illegal fishing supply chain” by mutual consent, tinged with the warmth of humanity.

The local officials were happy that the Taiwanese vessels provided job opportunities, while they might get something out of it themselves. The Taiwanese fishing boats were also happy to hire workers on-site, where they could land and get fresh water, showers, soft drinks, beer, proper meals, and sleep on comfy beds instead of inside rocking cabins. Why not? They did not have to bring workers from Taiwan, which saved them labour costs since the wages for Filipino workers was lower, while the catch was good and they got to live comfortably on shore, at the same time stimulating the local economy for Philippines officials — a win-win situation.

So, this was an “illegal fishing supply chain” by mutual consent, tinged with the warmth of humanity. I learned that, driven by shared interests, there were probably many more such cases. It was only because for Linapacan, the stories of marrying and having children were embellished and spread.

This was good news fodder that could be developed into a series, or even a book. But that would take at least a year, with financial support from some news agency. Given the circumstances at the time, that was not possible for me.

Unforgettable sea and sky

There is a little epilogue to this. I found out that the fishing boat captain was affiliated with the Donggang Fishermen’s Association in Pingtung. After returning to Taiwan, I immediately visited the association’s office in Donggang. To my great surprise, the captain and his wife happened to be there on business. I told him that I had travelled to Linapacan and met Gloria and his son. He looked at me in astonishment and said, “Since you mentioned Gloria, I believe you.” His wife sat poker-faced next to him.

You could take this news story as a romantic tale — a woman on a remote Philippine island holding her child, waiting for her husband to return from distant Taiwan on the next fishing boat. It could be written as Taiwanese rural literature. Or, it could be gossip — just another story of men acting on instinct, seizing the chance to mate like animals. You can imagine it however you wish.

But I can tell you: those scattered islands, the azure ocean and waves, and the star-filled sky at night were absolutely beautiful.

This was my first investigative report in my journalism career. Though it took me thousands of miles away, I managed to complete it in about two weeks. In my later years in journalism, some stories would take ten years to follow through. Compared with those, this one was short — but it gave me a sense of indescribable satisfaction and joy.

![[Big read] Prayers and packed bags: How China’s youth are navigating a jobless future](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/16c6d4d5346edf02a0455054f2f7c9bf5e238af6a1cc83d5c052e875fe301fc7)