My secret manuals of life

I have two "secret martial arts manuals".

In martial arts or wuxia novels, there are only two routes to learning martial arts: either find a master and beg him to teach you, or get your hands on a martial arts manual, shut yourself off in a mountain cave and practice day and night.

In a novel by Wolong Sheng (real name Niu Heting), there's a picture of a shepherd with his flock that marks out the location of a hidden treasure. Not only that, each sheep's posture gives clues to the moves of some unrivalled martial arts.

But in the novel, we only get to read the verbal instructions (usually passed down from masters to disciples) of the moves, and cannot see the sheep for ourselves to truly understand the exceptional martial arts.

The novel also says that one can easily become obsessed and go off the rails because they are unable to unlock the true significance of the final move.

Wuxia novelist Louis Cha (better known as Jin Yong) once said that he had visited Shaolin Temple, but the monks' skills he witnessed there were not as spectacular as that described in novels. And though there were some ancient secret manuals in the temple vaults, these were mostly medical recipes or prescriptions rather than martial arts manuals - real-life secret manuals are just different from those in novels.

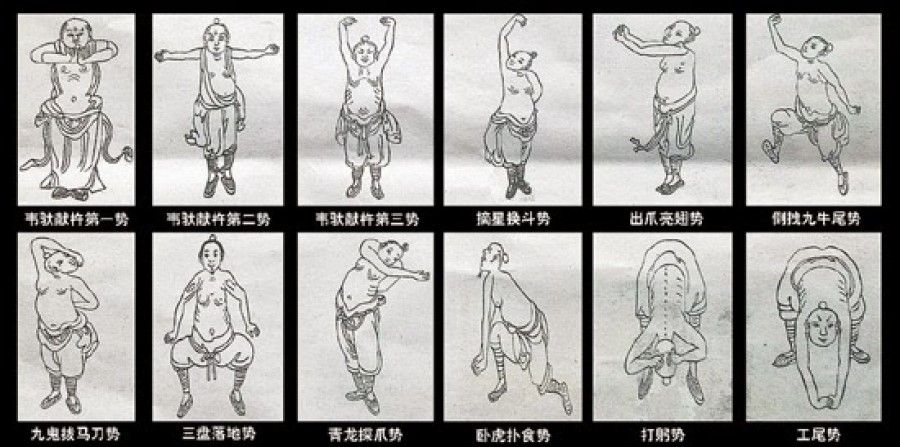

For instance, the actual ancient text《易筋经》(Yijin Jing, lit. Muscle/Tendon Change Classic) is not some record of a technique for unmatched internal energy or power, but an illustrated description of strengthening and health exercises that people did in the old days.

In the version that dates back to the Xianfeng Emperor of the Qing dynasty, the image for the first move (韦驮献杵第一势, lit. Wei Tuo Presenting the Pestle, Stance 1) just shows a bare-bodied monk with a cloth wrapped around his lower body, hands with palms together before his chest. One would not be able to learn the move by just looking at the picture.

Fortunately, there is a formula that goes with it: "Stand upright, look straight ahead; hands clasped, palms together before the chest; steady the breathing, quieten the mind; clear heart, respectful demeanour." (立身期正直,环拱手当胸,气定神皆敛,心澄貌亦恭) The images and text cross-reference one another, with one image showing the main stance, and a formula describing the entire movement from beginning to end.

Secret manuals of life

Back to my two "secret manuals".

One contains exercises for breathing techniques. They originated from a book that would have had ready explanatory diagrams, but I felt I wanted to write and draw the techniques myself with pen and paper, and so I have it - my own "secret manual".

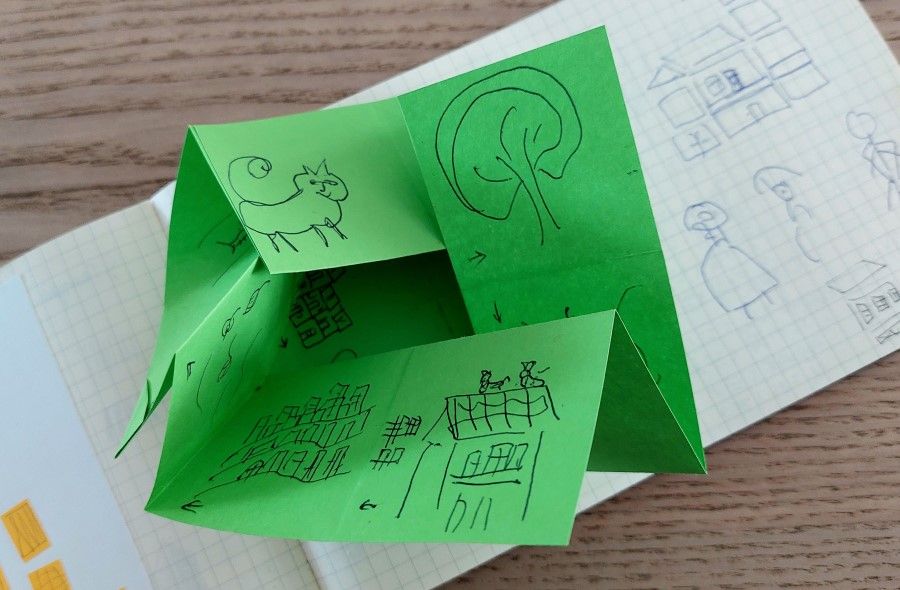

The ancient manuals were not easy to reproduce and there was only one diagram for each movement. In my drawings, I broke each movement down and drew small figures in static motion to demonstrate them, like an animation.

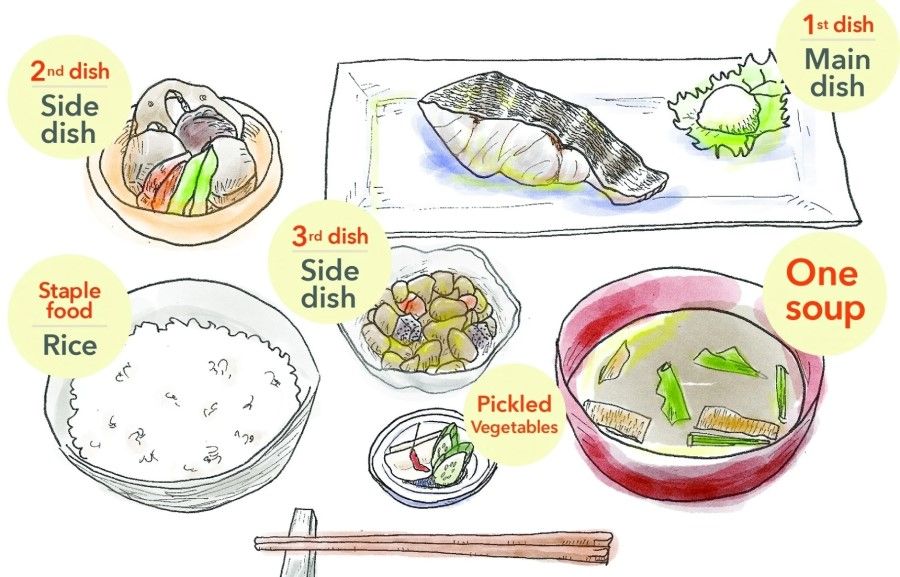

The second secret manual contains recipes for Japanese food. I once took a short Japanese cooking class, and the teacher's notes only listed down the recipes. I was afraid I would forget what to do after the class, so I took notes with text and drawings, clearly showing each ingredient and its quantity and the cooking method, much like the illustrated books that have become popular in recent years.

Nowadays, with videos, one can watch live demonstrations of new dishes on a mobile or laptop and follow along, which makes it much more convenient.

But flipping through that "secret manual" - which lists the special cooking equipment needed, the way to cut the ingredients, the plating style of "ichiju sansai" (一汁三菜, referring to one soup and three dishes) - I am still able to make a dish by following its text and images. Because it's my own notes, whatever I recorded were probably the details I took special note of, and they actually appear especially clear to me now.

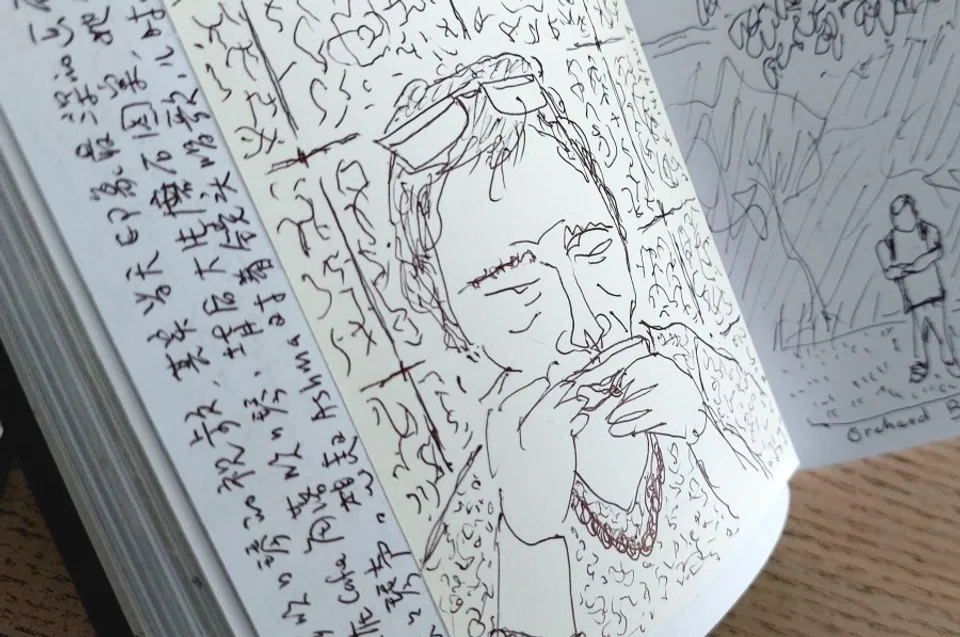

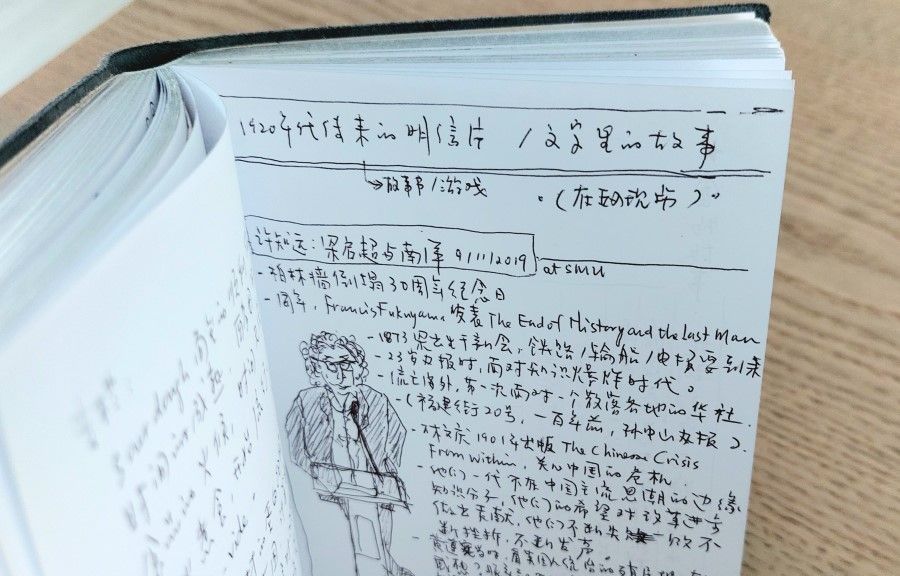

So, I usually still bring a notebook around to write things down and do simple sketches of what I see around me. I have quite a few notebooks with images and text - some are full, while others start off well but trail off - at first it is neat and properly written, but then left empty when it is barely half filled, as I get a new notebook.

Journeying and journalling

I probably started keeping notebooks on my travels.

Once, it dawned on me that I might miss out on some scenery if I just took photos, so I brought a little notebook along with my camera. The handwritten notes capture a sense of the times that is not found in beautiful landscape photos. Photos are a snapshot of a moment, but every time you re-read a handwritten journal, the word and pictures lead you into the beginning of a story.

Since then, I would bring along a notebook on my travels and take fewer photos. While previously I didn't keep a journal, I started writing down snippets of life, my thoughts, what I saw, excerpts of books, things I wanted to do, etc.

Flipping through a few pages, this was what I wrote after a major earthquake in Japan: "Read on the Prague Bookstore Facebook page that the Fukushima Aquarium ran out of electricity. The oxygen and water temperature of the tanks could not be replenished and regulated. Many fish, jellyfish, marine plants and amphibians slowly died. Only three staff left at the aquarium." (NB: The now-defunct Prague Bookstore was a secondhand bookstore in Taipei.)

The same night, I drew the bright round moon outside the window. It was only a few days later that I found out that was the closest the moon was to the earth in over a decade.

After the KTM trains stopped running, I passed by the Tanjong Pagar railway station and scribbled: "The railway station has been preserved as a national monument. It will be a railway station where no trains leave or arrive."

In Kyoto: "Went to Nishi Hongan-ji at noon. Passed through little streets and lanes, got to Higashi Hongan-ji after 3pm, nearly 4pm. Afternoon sutra readings were starting in the main hall. Followed and quietly sat on a tatami." That time, I only drew certain parts of the main hall. I drew the exterior of the temple on a subsequent trip to Kyoto.

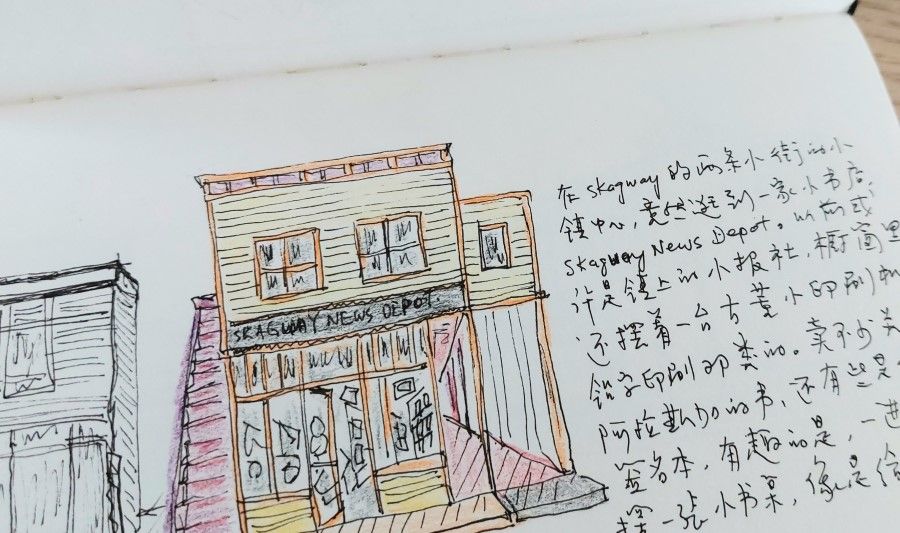

On a trip to Alaska: "In Skagway, a little town of a few thousand people. The city centre is just two small streets, but I manage to find a tiny bookstore. Perhaps it used to be the town's newspaper office; there is an antique miniature printing press in the window. The store sells many books on Alaska. There is a little desk at the entrance that looks like it's used for author signings." That year, we were preparing to take over Grassroots Book Room.

The same applies to writing and doodling - do it as if facing an eminent person, and being filled with a sense of excitement and uncertainty. This habit has been with me for many years.

Two pages have no text.

There are two trees by the roadside; behind the trees, a worksite is barricaded, bearing the logo of the National Parks Board. This was the train station opposite my old home. I wrote a piece on that station, describing the changes - from an expanse of wild grass when we first moved in, to trains whistling by at regular intervals; later, the grass was cleared to clamp down on illegal cigarette sales; then, the train services stopped and the station was moved; a new station was built, and the original site was closed off to be cleared and levelled, and planted with grass. In the 20 years I lived there, the backdrop of the little train station has kept changing.

It has been a few years since we moved away, and flipping through the book and looking at the picture again gives a complete story, which has not ended because we moved. If and when we go back one day, the scenery will be different again.

The formula for Wei Tuo Presenting the Pestle 1 says: "Steady the breathing, quieten the mind; clear heart, respectful demeanour." That describes the state that one should be in when practising Yijin Jing techniques. Cai Yong - a calligrapher, historian and politician of the Eastern Han dynasty (25-220 AD) - said of writing calligraphy: "Be focused, steady and collected, yet upbeat, as if facing a most respected person, and one will not do badly."

The same applies to writing and doodling - do it as if facing an eminent person, and being filled with a sense of excitement and uncertainty. This habit has been with me for many years.

Related: Must one read Chinese to appreciate Chinese calligraphy? | My childhood days in Xiamen Street, Taiwan: Of invisible warriors, string puppets and spring pancakes | Chinese bookshops in Singapore: Art salons of the 1970s and 1980s | An Egyptian-American architect's poignant photographs of disappearing Shanghai neighbourhoods