Can Malaysia handle intrusions by the Chinese air force?

The 31 May incident, in which 16 Chinese military planes entered the airspace above Malaysia's exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea, raises questions about Malaysia's ability to handle such occurrences in the future, says RSIS researcher Wu Shang-Su. He takes a hard look at Malaysia's airpower capabilities.

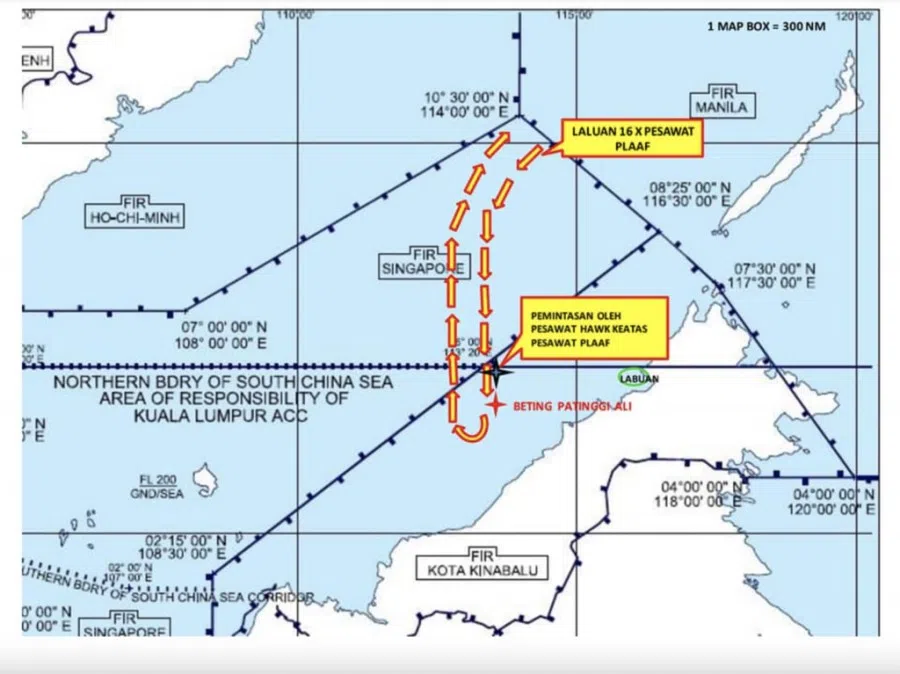

On 31 May, 16 Chinese People Liberation Air Force (PLAAF) planes entered the airspace above Malaysia's exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea, the largest Chinese air force entry into this airspace that has been publicly recognised by Malaysia. It is reported that the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) scrambled air assets from Labuan to track these Chinese planes. This headline-grabbing incident, and the possibility that this was not a one-off occurrence but a harbinger of more frequent and sustained PLAAF activity, raises the question of whether Malaysian airpower is ready for this looming scenario.

For more than a decade, Kuala Lumpur has faced challenges in developing or maintaining its air force. Slow economic growth and other priorities led to more constrained defence budgets. Despite the larger defence budget this year - constituting an increase of 1.8% over 2020 - the Covid-19 pandemic's economic and fiscal effects in Malaysia will limit defence spending going forward.

Strategically, the Lahad Datu armed conflict incident in early 2013, reoriented Kuala Lumpur's military modernisation programme back to counter-insurgency (COIN) concerns, including investing in COIN-related capabilities such as MD-530G light attack helicopters. In addition, this programme is addressing the needs for operations other than wars, such as disaster relief and counter-piracy. In contrast to these COIN and peacetime priorities, conventional warfare-oriented assets, such as RMAF fighters, are expensive to purchase, operate and maintain, making them attractive targets for delayed or cancelled procurement.

Since the procurement of 18 Sukhoi-30 MKM fighters in the late 2000s, the Malaysian air force has not introduced any new fighter aircraft, and some ageing airframes, such as the F-5E/Fs and MiG-29Ns, have been removed from service. The multi-role combat aircraft (MRCA) and light combat aircraft (LCA) projects would help fill this void, but the former has been postponed, and the latter is progressing slowly.

The Malaysian air force is attempting to maintain capacity by upgrading existing fighters, such as F/A-18Ds and Su-30MKMs, but the Hawk Mk-108/208s are not being upgraded, and the number of active services is falling. Although surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) also can serve air defence needs, the lack of visual contact capabilities of those in operation in Malaysia makes them unsuitable for intercepting foreign aircraft. All of Malaysia's SAMs are short-range ones for field air defence rather than covering large spans of airspace like that traversed by the PLAAF formation.

...if such PLAAF missions become frequent, like what Japan and Taiwan are encountering, the additional sorties and flight hours required of the RMAF would mean a greater maintenance burden.

Monday's incident suggests at least two Malaysian airpower challenges. First, Malaysia's existing fighters, including the sub-sonic Hawks, would be sufficient to scramble to track the PLAAF's slow-moving Il-76 and Y-20 transporter aircraft deployed over Malaysia's exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea this week. However, if such PLAAF missions become frequent, like what Japan and Taiwan are encountering, the additional sorties and flight hours required of the RMAF would mean a greater maintenance burden. As the Malaysian air force has suffered from some logistical issues, this greater burden could erode readiness. Since Malaysia must retain air defence over its whole territory rather than just the eastern states brought into focus on Monday, this capacity shortage challenge could be more serious.

Second, Chinese fighters, either from an aircraft carrier or land bases, may join future operations for escorting or other purposes. Therefore, Kuala Lumpur needs similarly advanced fighters for tracking or intercepting approaching foreign counterparts. In this contingency, the Hawks may not be sufficient, and the burden of operating the eight F/A-18Ds and 18 Su-30MKMs would be heavier. Aside from these hardware concerns, how to handle such a contingency without triggering inadvertent escalation would be a severe test for the RMAF.

As the need for greater Malaysian air defence capabilities, especially interception capacity is more pressing, the ongoing project to procure 36 LCAs is the best bet for enhancing this capacity. Supersonic models, such as the Korean FA-50s, Sino-Pakistani JF-17s and Indian Tejas, may be more suitable than sub-sonic ones. As the JF-17 model seems to be promising, whether or not its Chinese components affect the project's selection process bears watching.

Apart from new fighters, improving supporting infrastructure such as radars and airbases in East Malaysia would help accommodate more deployment.

The MRCA project also should be revived depending on the frequency and manner of future Chinese activities in Malaysia's exclusive economic zone and Malaysia's economic recovery from the pandemic. Apart from new fighters, improving supporting infrastructure such as radars and airbases in East Malaysia would help accommodate more deployment. Although airborne early warning (AEW) aircraft will enhance Kuala Lumpur's surveillance capacity, their procurement would take longer than the current projects to realise.

These steps in response to last Monday's incident are consistent with the recent defence white paper's "two-theatre" strategy and call to build up forces in the eastern states. Owing to the South China Sea situation, Malaysia already has deployed more military assets to the eastern states that aided the response to the incident. The current capacity, though, may be insufficient if Beijing raises either the frequency of such operations or includes more advanced, lethal aircraft in them

The incident on 31 May may inspire a reorientation again of Malaysia's defence strategy and military modernisation programme away from COIN back to conventional warfare. Even though Kuala Lumpur's fiscal resources may not be as ample as in the 1990s, it is still able to enhance its airpower capacity with proper planning.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.