Has Prabowo changed Indonesia’s stance on the South China Sea?

A joint statement recently issued by the Chinese foreign ministry has caused much consternation among Indonesian observers, who fear that it signals a change in Indonesia’s stance towards territorial claims in the South China Sea. ISEAS academic Leo Suryadinata discusses the possible reasons for the statement, as well as its potential consequences.

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto embarked on a five-nation tour on 8 November, just 20 days after his inauguration, with China as his first stop. In fact, at the end of March this year, he had also visited China at the invitation of Chinese President Xi Jinping while still president-elect, publicly stating his commitment to continuing former President Joko Widodo’s policy of friendship with China.

This time, Prabowo visited China before visiting the US and received a warm welcome from Xi Jinping. Prabowo was visibly enthusiastic, and emphasised in his English speech that the region now needs collaboration, not confrontation. He expressed hope that cooperation between Indonesia and China could serve as a model for regional collaboration, and reiterated his life philosophy: “A thousand friends are too few; one enemy is too many.” He attributed this quote to an “ancient Chinese philosopher”, and even said it in Mandarin to leave a strong impression on his Chinese hosts.

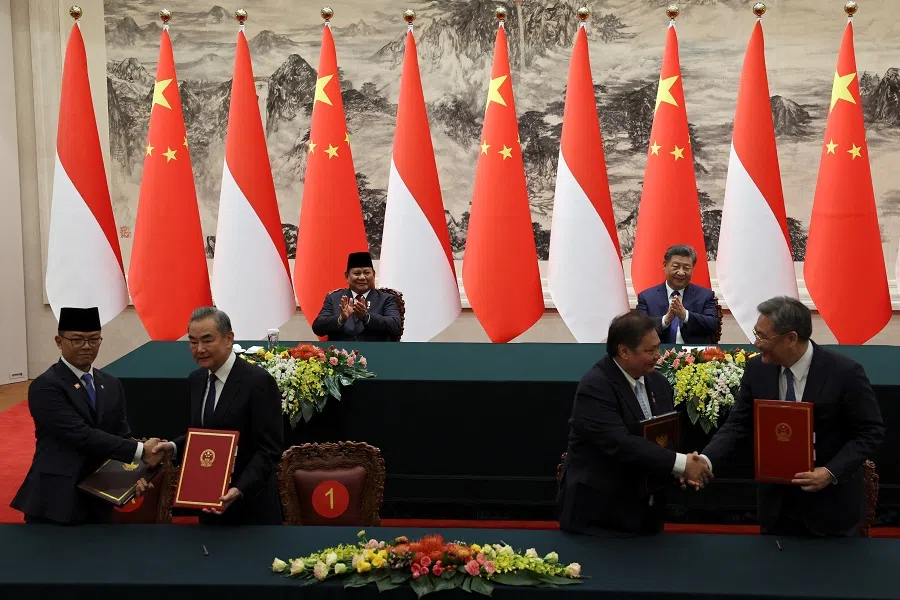

It was evident to keen observers that, like Xi Jinping, Prabowo intends to deepen Indonesia-China relations. On the second day of his visit, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a joint statement in English on enhancing the strategic partnership between both countries. On the third day, Prabowo joined a ceremony on economic cooperation, witnessing the signing of US$10 billion worth of contracts between Indonesian and Chinese companies.

Indonesia has consistently refused to recognise the nine-dash line and has declined to engage in negotiations with China.

It is worth noting that the joint statement was released by the Chinese side, and one of its statements on maritime cooperation has sparked controversy: “The two sides reached important common understanding on joint development in areas of overlapping claims and agreed to establish an Inter-Governmental Joint Steering Committee to explore and advance relevant cooperation based on the principles of ‘mutual respect, equality, mutual benefit, flexibility, pragmatism, and consensus-building,’ pursuant to their respective prevailing laws and regulations.”

Change of stance or misunderstanding?

The joint statement has stirred intense debate both within and outside Indonesia. Indonesian academics and observers have questioned the Prabowo administration’s seeming alteration of Indonesia’s stance on the Natuna Sea (the portion of the South China Sea claimed by Indonesia). They feel the statement gives the impression that Jakarta now recognises China’s nine-dash line, a claim that Indonesia has long refused to acknowledge.

Indonesia has consistently maintained that it is not a claimant state in the South China Sea dispute, so how could there be “overlapping claims”? China and Indonesia are both signatories of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Indonesia has a 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), a small portion of which overlaps with China’s nine-dash line. However, Indonesia has consistently refused to recognise the nine-dash line and has declined to engage in negotiations with China.

Chinese fishing vessels and coast guard ships frequently intrude into Indonesia’s EEZ. Some fishing vessels have been detained, and coast guard ships have been expelled. According to reports, a week before the joint statement was released, Indonesia had expelled a Chinese coast guard ship that entered its EEZ.

Discrepancies between Chinese and Indonesian statements

On 9 November — the same day that China released the English-language joint statement — the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a document in Bahasa Indonesia on the statement. This latter document was released to the media:

If Indonesia does not acknowledge the nine-dash line, how could there be “overlapping claims” between Indonesia and China, or joint development of such areas?

“Indonesia and China agreed to establish maritime cooperation to support peace in the South China Sea… This cooperation aims to be a model of peace and friendship in the region, with a focus on the economy, especially in the fields of fisheries… This cooperation will also be carried out in accordance with the laws and regulations of each country. For Indonesia, its implementation must follow rules related to territory, international maritime law, as well as regulations… without changing existing international obligations.

“However, Indonesia emphasised that this cooperation does not mean that Indonesia recognizes China’s ‘nine-dash line’ claim, which is considered to have no basis in international law and is contrary to the 1982 UNCLOS. Indonesia continues to maintain its sovereignty and sovereign rights in the North Natuna Sea.”

In the Indonesian document, there is no mention of joint development of “overlapping claims”, nor did Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs call for any corrections to the wording of China’s joint statement. Instead, it clarified that maritime cooperation with China does not equate to Indonesia’s recognition of the nine-dash line. If Indonesia does not acknowledge the nine-dash line, how could there be “overlapping claims” between Indonesia and China, or joint development of such areas?

In an interview programme, Indonesian Deputy Foreign Minister Arif Havas Oegroseno explained that the Indonesian government has never recognised the nine-dash line, so there is no overlapping claim between the Natuna Sea and Chinese waters. He also revealed that ASEAN member states have approached him for clarification, and he has explained Indonesia’s stance, emphasising that border agreements with neighbouring countries remain unchanged.

However, when pressed by the host to discuss joint development in the Natuna Sea, Havas merely stated that any joint development projects must be studied and decided by the Indonesian government in accordance with both countries’ respective laws and regulations. Implicitly, this suggests that Indonesia’s current laws and regulations cannot accept a development model based on “overlapping claims” as mentioned in the joint statement.

Prabowo may not have fully considered that without resolving sovereignty disputes, claimant states are unlikely to engage in joint development of contested waters.

A costly blunder?

Was the English version of the Indonesia-China joint statement a diplomatic misstep on Indonesia’s part? It seems that no senior Indonesian diplomats were involved in drafting the statement. Foreign Minister Sugiono is young and inexperienced, and not from a diplomatic background. After the controversy arose, the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs quickly attempted to rectify the situation, reiterating its rejection of the nine-dash line and indirectly denying the existence of “overlapping claims”. However, the ministry stopped short of admitting any error.

During Prabowo’s visit to China, he appeared to be aiming to position himself as a regional leader. He sought to convey to the world that what is needed in the South China Sea is peace and cooperation, not confrontation and conflict. Joint development with China is a good approach. However, Prabowo may not have fully considered that without resolving sovereignty disputes, claimant states are unlikely to engage in joint development of contested waters.

Despite having just assumed office, Prabowo already has his own ideas about international affairs. He sees Indonesia as a major power and, as president, seeks to demonstrate his leadership capabilities. He aims to maintain independence amid US-China competition and position Indonesia as a regional leader. He intends to maintain friendly ties with both China and the US. The joint statement can be viewed as a gesture of goodwill towards China. However, with the inclusion of wording unfavourable to Indonesia regarding maritime cooperation, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs made indirect revisions to save face.

The phrasing about “joint development in areas of overlapping claims” in the English-language joint statement is seen as symbolic, without legal binding force. However, many observers worry that such language creates the impression that Indonesia’s position is wavering.

Analysts believe that Prabowo is a nationalist who will protect Indonesia’s territorial integrity and promote Indonesian nationalism. So, when the term “overlapping claims” appeared in the joint statement, some Indonesian analysts expressed confidence that Prabowo would adhere to Indonesia’s longstanding stance against the nine-dash line and avoid compromising on sovereignty.

The phrasing about “joint development in areas of overlapping claims” in the English-language joint statement is seen as symbolic, without legal binding force. However, many observers worry that such language creates the impression that Indonesia’s position is wavering. This could harm the interests of claimant states in the South China Sea dispute and potentially lead to friction among ASEAN countries — an outcome Prabowo likely did not anticipate.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “普拉博沃改变印尼对南中国海立场?”.