A Singaporean in China: Contact tracing lays bare the lives of ordinary Chinese

Zhang Ming (pseudonym), who lives on No. 9 Hepingli East Street in Beijing, is a primary two student at Dongcheng district Hepingli No. 4 Primary School.

On 10 March, his parents sent him to school in an electric vehicle and he ate at KFC in Heping Xincheng after school. Over the next few days, Zhang had a swimming lesson at Sunshine Four Seasons Swimming Fitness Club, attended calligraphy lessons at Heping Zhixing Qinzi Square and took rollerblading lessons at Ocean We-life Plaza. On another day, he bought a drink at Lijia Baby at 5.38 pm, and a minute later, he was shopping at Kidsland. From 5.52 to 6.30 pm, he had dinner at Burger King before leaving the mall at 7.03 pm to buy fruits before heading home.

Meanwhile, Yi Fan (pseudonym) is a fan of role-playing game jubensha (剧本杀), escape rooms and barbecues. Within the span of 11 days in September last year, she played jubensha four times and an escape room once, and had two barbecue meals in Harbin. She also visited a bookshop and an aesthetic clinic.

I know where they live and what they did for those few days, all because they tested positive for Covid-19.

I do not know Zhang and Yi personally. I am not even sure about their gender. But I know where they live and what they did for those few days, all because they tested positive for Covid-19. The Chinese government has been releasing information on the places visited and activities of Covid-19 patients in the days leading up to their positive results.

Contact tracing reveals different facets of society

Reporting a person's whereabouts, to the point of minor details such as the minute they entered a shop, what they had for dinner and what is their home address (barring the apartment unit number) is the norm in China now. While the original intention was to curb the spread of the virus, there have been many unintended consequences.

For example, a noodle eatery in Suzhou became a place of interest after investigations showed that two people who tested positive for Covid-19 had patronised the shop at exactly 7.49 pm a few days in a row. This led curious diners to visit the eatery once it reopened for business.

However, there is a dark side to this phenomenon as well. Some Covid-19 positive patients were doxxed and had their personal particulars leaked online just because netizens disagreed with the lifestyles reflected in their contact tracing records.

Nonetheless, most Chinese seem to have no qualms about losing some personal privacy in exchange for the well-being of the general public. Some netizens even joked about how this practice has successfully deterred them from going to questionable places such as illegal massage parlours for fear of being exposed.

Putting the issue of privacy aside, these epidemiological investigations (流调), or contact tracing records, are intriguing to read as they reveal the different facets of Chinese society.

Social media users on Weibo have pointed out how the contact tracing records of Chinese in various cities reflect the differences in people's lives.

While some people's list of activities is long and elaborate, others can be summed up in two sentences.

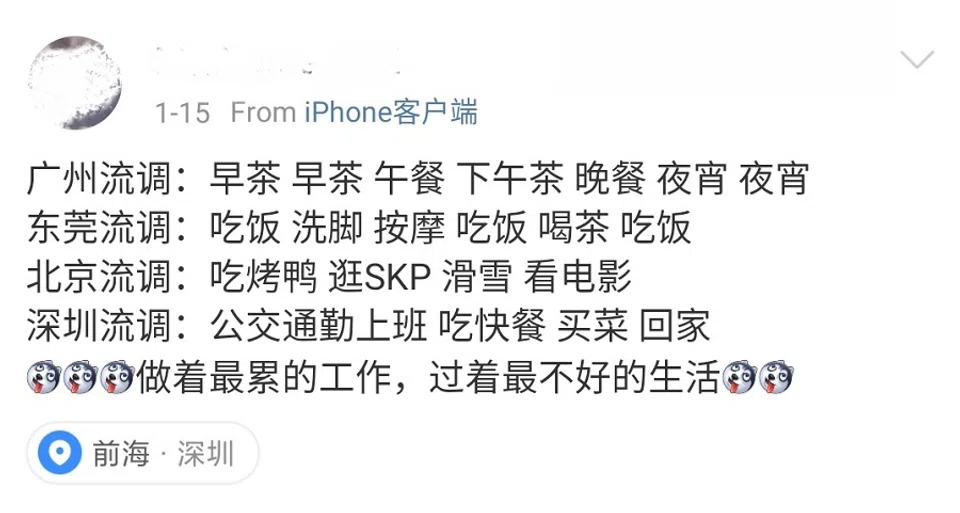

One user summarised the situation in jest, "Guangzhou's records: two breakfasts, lunch, tea break, dinner and two suppers; Dongguan's records: eating, foot washing, massage, more eating, drinking tea and even more eating; Beijing's records: eating Peking duck, shopping at Shin Kong Place [a luxury mall], skiing and watching movies; Shenzhen's records: people taking public transport to work, having fast food, buying groceries and going home. People doing the toughest jobs live the worst lives."

Migrant workers vs bank staff

While some people's list of activities is long and elaborate, others can be summed up in two sentences. One contact tracing record circulating on Weibo states that a man, designated as confirmed case number five, had breakfast and then went to work at a factory at 7:30 am with his wife in an electric vehicle. The two knocked off from work and went home at 9.15 pm. And this was repeated for the 13 days recorded from 24 February to 9 March.

In January this year, a migrant worker in Beijing drew netizens' attention when his contact tracing record showed that he had visited 28 places in 18 days - not for the purpose of visiting tourist attractions, but to move construction materials during the wee hours. He was called "China's most hardworking man based on contact tracing records" on Weibo, and quickly became a trending topic.

The Chinese media later reported that the migrant worker, known only as Yue, was previously a fisherman in Weihai, a coastal city in eastern Shandong Province. He and his wife have two sons, and their lives changed in 2020 after their elder son, who was 19 years old then, went missing. The couple claimed that the local police station ignored their pleas for help.

Hence, Yue took it upon himself to make his way across China in search of their son, taking on odd jobs along the way to provide for his six-person household which includes his paralysed father. Last year, Yue arrived in Beijing where his son used to work as a cook. Yue took on odd jobs from moving construction materials to collecting garbage, earning 200 to 300 RMB per shift and sleeping four to five hours a day.

At around the same time, contact tracing records of another Covid-19 positive case showed that a person spent the first ten days of the year working in a state-owned bank in Beijing, shopping at luxury stores such as Dior and jewellery stores such as Chow Tai Fook and Chow Sang Sang, watching a talk show and even skiing.

Netizens compared and bemoaned the parallel lives of the two people living in the same city saying, "One is in China, and the other is also in China."

The release of contact tracing records has merely laid bare the realities that people from all walks of life face.

Some media outlets have also jumped at the opportunity to criticise China for declaring that the country has eliminated extreme poverty when there are clearly still people like Yue working multiple jobs to make ends meet.

Indeed, inequality is a perennial problem in every city and country in the world, and even in some of the richest countries, the Gini coefficients are higher than average. The lives of those in the lower socioeconomic classes go largely unnoticed by the majority that makes up the middle class, partly because they are preoccupied with their own problems and stresses in life, and partly because these workers usually toil in obscurity behind tall barricades of construction sites, use a separate service elevator or work in the dead of the night to ensure that the city can operate smoothly the next day. The release of contact tracing records has merely laid bare the realities that people from all walks of life face.

Related: US academic: Equality is a myth, whether in the US or China | Why rumours spread faster than outbreaks in Shanghai | As the virus spreads, can China calm its people and contain the outbreaks? | When Beijingers can't return home: Is China going overboard with its zero-Covid measures? | Is China taking policies to the extreme to achieve zero-Covid? | New Great Wall of China against Covid-19 built with flesh and blood of the little people