[Big read] Not a zero-sum game: Semiconductor pie big enough for Singapore and Malaysia

Just as the chip war between China and the US turns red hot, the spotlight has turned to Malaysia, which has been described by some Western media as the inadvertent winner of the contest. What strengths does this close neighbour of Singapore possess? Can Singapore keep its edge? Lianhe Zaobao journalist Yush Chau takes a look at the current state of the semiconductor industry in both countries, the possible challenges they face and the outlook for the industry’s development in Southeast Asia.

Malaysia was once the shining star of the chip industry in the 1970s, drawing international chip manufacturers to its shores. Following the rise of Samsung and TSMC, however, it soon fell by the wayside, sidelined by South Korea and Taiwan.

But the past three years have seen the tide turn once again: Malaysia’s semiconductor sector is now booming and investment is gushing in.

According to the data that Dato’ Seri Wong Siew Hai, president of the Malaysia Semiconductor Industry Association (MSIA), shared with Lianhe Zaobao, from 2021 to 2023, the country’s electrical and electronics products (E&E) industry — which includes semiconductors — drew investments worth 262 billion ringgit (US$55.9 billion), far exceeding the 216 billion ringgit figure from 2000 to 2020. “This shows the tremendous progress Malaysia’s E&E sector has made in the past few years as an ideal location for semiconductor companies,” Wong said.

As significant investments pour in, Malaysia’s semiconductor industry is thriving. Does this development cast a shadow over Singapore’s prospects?

Singapore supplements its regional counterparts to provide an attractive location for upstream chip manufacturing, benefitting other SEA markets as well. — Lai Wai Kit, partner, EY-Parthenon

Singapore strong in upstream chip production

Lai Wai Kit, a partner with EY-Parthenon, part of consulting firm EY, pointed out that Singapore’s advantages in global connectivity, access to human capital, ease of doing business, regulatory stability, strong legal framework and intellectual property protection laws has enabled the country to remain an attractive destination for semiconductor companies.

In addition, the Singapore government has rolled out measures to support the development of the industry, including the Electronics Industry Transformation Map and investments of S$180 million (US$144.9 million) to set up the National Semiconductor Translation and Innovation Centre to develop research and development (R&D) capabilities and local talent, which will go a long way in strengthening Singapore’s position as a key manufacturing hub for semiconductors and high value-added electronics.

Lai does not see the competition as a “zero-sum game”. He thinks that Singapore supplements its regional counterparts to provide an attractive location for upstream chip manufacturing, benefitting other SEA markets as well.

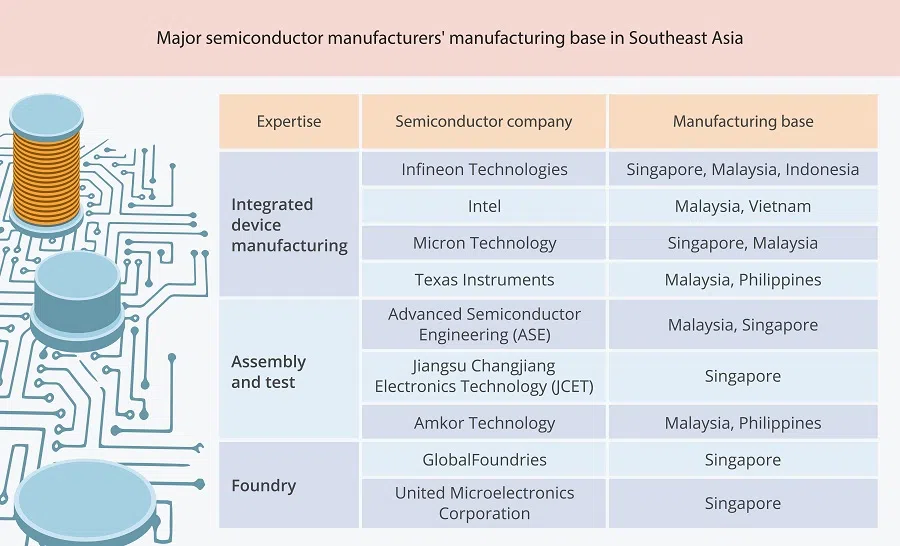

Terence Koh, head of Technology, Media and Telecommunications, Sector Solutions Group at UOB, holds a similar view: Malaysia’s continued momentum to grow this sector will be complementary to Singapore. Malaysia plays a critical role in the assembly and testing of chips while Singapore has leading companies carrying out R&D along with wafer fabrication work.

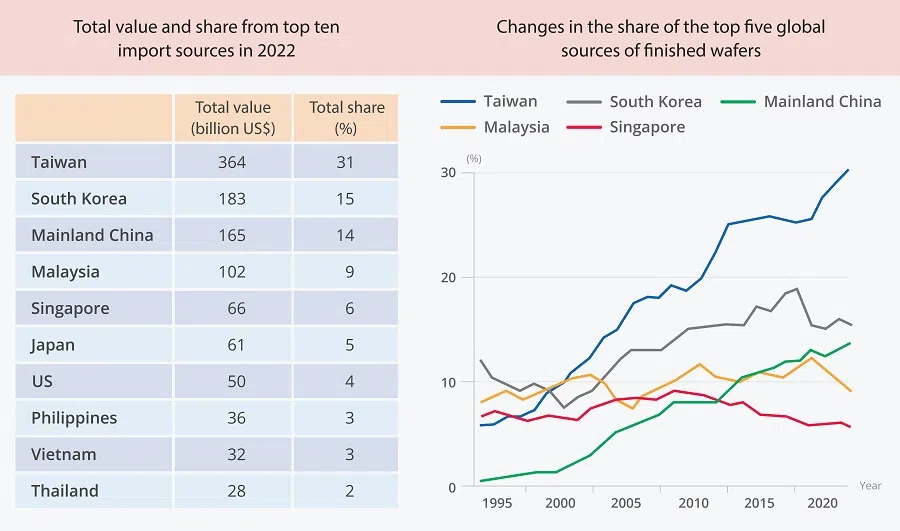

Malaysia’s strength on the semiconductor manufacturing supply chain lies in packaging, assembling and testing, and it has a global market share of 13% in semiconductor packaging and testing.

Malaysia has an edge in the downstream

Semiconductor production involves design, manufacturing, assembly, testing and packaging (ATP). R&D and manufacturing are the most technology and capital-intensive stages, and are also the most profitable part of the supply chain.

During the ATP segment, wafers that have met testing requirements are assembled according to their model type and functional requirements to obtain individual chips. That is, packaging and testing come near the end of the semiconductor production process, with lower added value, which also means lower profits.

Malaysia’s strength on the semiconductor manufacturing supply chain lies in packaging, assembling and testing, and it has a global market share of 13% in semiconductor packaging and testing. The Malaysian government has already set a target of increasing its market share to 15% by 2030.

According to data from McKinsey Global Institute, 9% of finished chips came from Malaysia in 2022, with a total value of approximately US$102 billion, putting it fourth in the world, behind Taiwan, South Korea and mainland China. Singapore ranked fifth.

Malaysia has also been the biggest source of chips to the US for several years now: at over 20% by value annually, and with an annual value of US$18.9 billion in 2022, more than Taiwan, South Korea and mainland China.

Penang, the centre of Malaysia’s semiconductor sector, has an area of 1,049 square kilometres — 40% bigger than Singapore. Several of the world’s biggest chip makers including Intel and Micron from the US, and Infineon from Germany, have set up bases there. They have also been upping their investments in Penang in recent years.

Intel is one such example. The company first expanded to Penang in 1972, setting up its first packaging and testing plant outside of US borders, followed by an R&D and design centre. Intel has invested another US$7 billion in new facilities there, including an advanced packaging plant that is slated for completion this year, and another packaging testing plant in Kulim, Kedah, near Penang.

Micron has also injected a further US$1 billion for a second packaging testing plant in Penang, while Infineon is investing up to 5 billion euros (US$5.4 billion) in Kulim to build new facilities that will expand its capacity in producing 200mm diameter silicon carbide (SiC) wafers to meet the growing demand from the renewable energy and electric vehicles (EV) sectors.

Malaysia faces talent shortage in its bid to move up value chain

MSIA’s Wong Siew Hai noted that Malaysia has built up over 50 years of experience in semiconductor manufacturing, and on top of offering excellent infrastructure, it is free of natural disasters, is peaceful with a pro-business stable government, and also has a talented workforce.

In addition to chip packaging and testing, Malaysia is trying to move upstream in semiconductor manufacturing by establishing itself in areas including wafer fabrication and the integrated circuit (IC) design. But success will depend on its ability to deal with a shortage of talent.

On 23 April, the Malaysian government announced the establishment of the largest IC design industrial park in Southeast Asia, slated to start operations in July this year. Government support in the form of subsidies, tax breaks, visa waivers and other incentives will also be provided to attract tech titans and talents from around the world.

Malaysia, however, is facing a brain drain.

Helen Chiang, lead of Asia semiconductor research at IDC, observed that wafer fabrication plants usually require massive investment, making it tricky to find tenants — Malaysia’s shift into IC design may be the right move, but a deciding factor will be its ability to draw adequate talent and attract start-ups with high potential.

She stressed how crucial attracting and retaining talent was in the IC design sector, “Training an engineer will take at least three to five years; if there’s no foundation internally, the best way would be to bring in talent.”

Malaysia, however, is facing a brain drain. Liew Chin Tong, Malaysia’s deputy minister of investment, trade and industry, noted candidly that the semiconductor industry often complains about talent shortage in the country, but the problem can be attributed to wage levels.

In his article published on the website of Australia-based East Asia Forum, he wrote that many of Malaysia’s skilled workers, such as engineers and technicians, pursue employment in Singapore where the pay is better. Official figures show that the median monthly wage in manufacturing for 2022 in Malaysia was 2,205 ringgit — below the nation’s median monthly wage of 2,424 ringgit.

Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam may benefit from demand for AI chips

As the chip war between China and the US continues to escalate and geopolitical relations remain tense, Wong Siew Hai noted a shift in the global semiconductor supply chain from “just in time” to “just in case”; a theme that repeatedly crops up in investment decisions is: “A resilient and secure supply chain.”

Although microprocessors and memory chips manufactured directly by Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam make up a very small share of the market, they provide professional services on the downstream in packaging, assembly and testing...

Wong observed that geopolitical tensions around the world and regional conflicts have driven the semiconductor industry to seek out ways to mitigate supply chain risks, considering strategies such as “China plus one”, “Taiwan plus one”, “US plus one”, and “Europe plus one”. This has given Southeast Asia the opportunity to step up as a destination for chipmakers looking to expand.

Tengku Zafrul Aziz, Malaysia’s minister of investment, trade and industry, told the New York Times that US and European companies, and even Chinese companies want to diversify out of China, to sidestep US sanctions. The “China plus one” strategy enables investors to keep their China investment while finding ways to spread the risk.

The high-income and developing economies of East Asia and Southeast Asia account for 80% of the world’s semiconductor production.

According to the Asian Development Outlook published in April by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) will drive an increase in the demand for microprocessor and memory chips, which is projected to bring about an increase in semiconductor exports from Asia.

Although microprocessors and memory chips manufactured directly by Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam make up a very small share of the market, they provide professional services on the downstream in packaging, assembly and testing, so ADB expects these economies to benefit from the increased demand driven by the rapid development of AI all the same.

... the broader Southeast Asia region will continue to benefit from the growth in the semiconductor industry, which is projected to become a trillion-dollar industry by 2030.

Singapore: attract global investments to bolster supply chain status

In response to enquiries from Lianhe Zaobao, a spokesperson from the Singapore Economic Development Board stated that Singapore welcomes more investment into the region to build a more resilient and integrated semiconductor ecosystem.

In addition, Singapore and Malaysia have developed their respective semiconductor industries over the years in line with global growth. Both countries’ industries can complement one another, and the broader Southeast Asia region will continue to benefit from the growth in the semiconductor industry, which is projected to become a trillion-dollar industry by 2030.

The spokesperson also said Singapore’s robust intellectual property protection regime, highly skilled workforce, advanced research capabilities and efficient supply chain ecosystem continue to attract semiconductor companies.

“Singapore will bolster its position in global semiconductor supply chains by continuing to anchor investments from leading global companies, doubling down on R&D investments in emerging semiconductor technologies, and expanding the talent pipeline.”

In recent years, investment in Singapore’s semiconductor sector has already been on the rise. Taiwanese chipmaker UMC injected US$5 billion to set up a new wafer fab in the country, and GlobalFoundries — the world’s third largest semiconductor contract manufacturing and design company — also invested US$4 billion to expand their facilities in Singapore.

But competition is stiff. With the race to control chip production and technology between major countries in the world, the contest to attract high-end semiconductor investments has also heated up — huge government subsidies are being offered to attract chip makers. Singapore’s Prime Minister Lawrence Wong had admitted previously that a small country such as Singapore would not be able to join the subsidies race.

At the opening ceremony for GlobalFoundries’ new plant in September last year, PM Wong said Singapore would not be able to compete in all areas of semiconductors, and probably will not be able to compete in the high-end space either, but the country will continue to build on the competitive advantages and strengths in specialty chips. In this year’s budget speech, PM Wong also reiterated that while the country will not engage in the “subsidy arms-race” with big countries, it will not stand by and do nothing, and will continue to attract high-value investments.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “非零和博弈 新马可共享半导体大饼”.