What I Ching and the mangrove tree flowers tell us about life

Chiang Hsun contemplates the transience of life as he observes the fleeting lifespan of mangrove tree flowers found along the riverbanks of Southeast Asia, southern China and elsewhere. Every flower has its own place and purpose, but like life, its brilliance is extinguished all too fast. How can one discern the meaning of life then? Perhaps the three-thousand-year-old book of I Ching offers us some clues.

Summer solstice. The Barringtonia racemosa (powder-puff tree) flowers by the river bank are in full bloom. Tassel after tassel, their pale pink stamens tremble in the wind. Set against the clear blue sky, they exude a southern charm.

The scent of the Barringtonia racemosa is fragrant and strong, attracting bees and butterflies hungry for nectar. This is a tropical plant with a short flowering span. Pollination and fertilisation must be completed quickly. Not only does it have a scent that attracts bees and butterflies, its male and female reproductive organs - the stamen and pistil - are exposed for all to see, allowing insects to rapidly facilitate the pollination process.

Nature's sexual and reproductive systems are especially lustful in the hot summer, just like the buzzing and clicking songs of a tree of cicadas. As the night draws in, Barringtonia racemosa flowers blossom like clusters of fireworks. They are a spectacular feast for the eyes indeed.

Splendid, magnificent, and fleeting, the Barringtonia racemosa flowers are indeed like fireworks. After just one night, fallen and withering flowers fill the ground - the pale pink fades away, leaving behind a sea of white pom poms.

Summertime in the south. Life is passionate and short. The primitive reproductive processes are direct and straightforward. There is nothing coy or restrained about it.

. . . . . .

The Barringtonia racemosa flowers not only attract bees and butterflies, but catch the attention of tourists who stop in their tracks, take out their cameras, and snap away in admiration of their beauty.

After a short flowering span, long braids of fruit hang from the mangrove tree. Withered flowers lie on the ground like stars that have fallen off the night sky. They were still so splendid and brilliant when they fell - like magnificent fireworks, they were fleeting and so ravishing that they were even startling; the life cycle of a universe - formation, existence, destruction and emptiness - has become just a memory.*

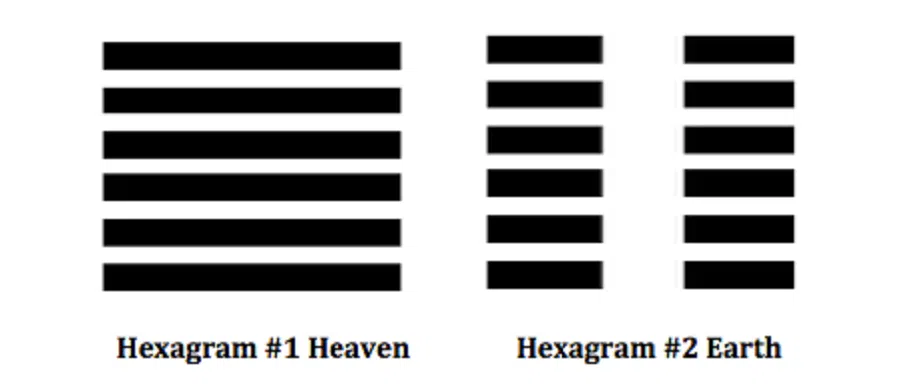

Today, I studied I Ching's (《易经》) Kun hexagram (坤卦) again.** Line 5 (六五) shows "a yellow skirt that symbolises great auspiciousness" (黄裳元吉). The fifth line enters the heavenly domain, as with the fifth line (九五) of the preceding Qian hexagram (乾卦), which shows "a flying dragon in the sky" (飞龙在天), followed by "an arrogant dragon with regret" (亢龙有悔).

Reading both the Qian and Kun hexagrams together, I'm especially fond of Kun's heavenly domain, that is, the yellow skirt that symbolises "great auspiciousness". Yellow is an earth tone that is not boastful, and a skirt is to be worn on the lower body, symbolising a low profile and humility. Thus, it is of great auspiciousness and the only one time that great auspiciousness appeared in the whole of I Ching. It is perhaps only of great auspiciousness when one acts moderately and plays his part.

This morning, I will just focus on looking at these fallen flowers. They bloomed and were admired. Now they have fallen, and turned to dust and mud in the wind and rain.

Editor's Note:

*In Buddhism, one mahakalpa (great kalpa), or period of time between the creation and a recreation of a world or universe, consists of the kalpas of formation, existence, destruction and emptiness.

**The Kun hexagram, is the second of 64 hexagrams in the I Ching. It is the yin to the yang of the first Qian hexagram. The lines of the Kun hexagram follow this rule and are presented in three different domains: earth, humanity, and heaven. Lines 1 and 2 belong to the earthly domain; 3 and 4 the human domain, and 5 and 6 the heavenly domain.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)