What's stopping Hong Kong from fixing its housing crisis?

Home to 7.5 million people, Hong Kong has the world's least affordable housing market. While the Hong Kong government has put many housing policies in place, and see the importance of solving the housing issue, why is it so hard for Hong Kong to make progress in this area? Caixin journalists Zhou Wenmin and Wang Duan report.

(By Caixin journalists Zhou Wenmin and Wang Duan)

In the face of daunting economic struggles, the world's priciest property market just keeps getting more expensive.

Hong Kong, home to 7.5 million people, has the world's least affordable housing market with the average price for commercial housing hovering around HK$200,000 (US$25,764.50) per square metre. Meanwhile, the average waiting time for subsidised public housing has climbed to 5.8 years.

Hong Kong has topped the global list of most expensive housing markets for 11 consecutive years. According to a report from the international public policy advisory company Demographia earlier this year, it would take an ordinary family nearly 21 years to buy a home in Hong Kong, and that doesn't even take into account spending on daily necessities.

"Now it's getting worse," said Ryan Ip Man Ki, head of land and housing research at the Our Hong Kong Foundation (OHKF).

Improving housing affordability has been the top concern of every Hong Kong government. In an interview with Caixin shortly after she took office in 2017, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam said housing policy was the top priority.

Although officials have long agreed that the problem can be solved only by increasing supply, the shortage has persisted for years.

In 2021, the central government made a rare public statement on Hong Kong's housing issue. Vice-Premier Han Zheng acknowledged the urgency of solving the city's housing difficulties during the annual gathering that March of national legislators in Beijing.

"Hong Kong's housing issue is a result of Hong Kong's history and development," Han said. "It is not an easy task to solve this issue, but there must be a start."

Housing shortages and surging prices stemming from the city's lack of land for residential housing development has plagued the city for nearly two decades, reflecting flaws in Hong Kong's land development mechanisms. The land issue has become a root cause of Hong Kong's social and economic problems, experts say. In addition, vested interests in the city's land market, with entangled ties involving industry organisations and businesses, have hindered efforts to make changes.

"The next chief executive can make history as long as the housing issue is fixed," a Hong Kong government official said.

But the area of land for building houses accounts for only 7%, which has remained almost unchanged for the past 15 years.

Scarce land

Ip said the shortage of land and housing is getting worse, and Hong Kong is caught in three "fast knots" - the low supply of "ready-made land" or land that is flat, equipped with well-established urban infrastructure and can be directly used for construction; low completion rates; and low living quality. The OHKF was initiated by Hong Kong's first chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa.

Over the past two decades, Ip said, Hong Kong has not implemented large-scale land development plans, causing the supply of land available for development to peter out. The dearth of new land is the fundamental cause of Hong Kong's awkward housing issue, characterized by being expensive, small and crowded. But does Hong Kong truly lack land?

According to 2019 data from the government planning department, Hong Kong covers a total of 111,100 hectares (429 square miles). Of that, the downtown area or land used for construction and development accounts for 27,500 hectares, or 25%, and the area of country parks accounts for 42%. But the area of land for building houses accounts for only 7%, which has remained almost unchanged for the past 15 years.

"We do have land, but not much," Lam told Caixin in 2017, as 70% of Hong Kong's land has not yet been developed. "Now, what we face is the lack of a social consensus on the utilisation of 70% of the land, whether some greening land should be developed or a large-scale land reclamation should be conducted outside of Victoria Harbour."

An application for redevelopment usually takes at least six years, and the subsequent construction work takes an additional four to five years. In addition, some projects may face opposition from the public, forcing a lengthy judicial review.

Supply bottleneck

After Leung Chun-ying took office in 2012, he stressed increasing the housing supply, mainly by diverting some non-residential land for housing development. By 2017 when Leung left office, the Hong Kong government had selected 215 land plots that could be used for residential construction in the short and medium term. As of April 2021, 70% of those plots had been redeveloped for residential use or were under construction. In the next 10 years, around 40% of new public housing buildings are expected to appear on those parcels.

However, the Hong Kong government recently slowed the land redevelopment program, partly due to complicated administrative approval procedures. An application for redevelopment usually takes at least six years, and the subsequent construction work takes an additional four to five years. In addition, some projects may face opposition from the public, forcing a lengthy judicial review.

At the end of 2015, Paul Chan Mo-po, the then-secretary for development and now financial secretary, said a major factor slowing the redevelopment work was opposition from neighbourhood residents, who often raise concerns over the projects' impacts on local traffic, the environment and other issues.

"Redevelopment to provide housing supply in the short to medium term will be difficult, but we must be determined and courageous, without fear of litigation," one government official said.

However, Ip argued that while redevelopment may increase the supply of residential land in the short term, it is merely a change in the nature of land use rather than the addition of new land. In his view, only the development of new land such as that of new development areas and land reclamation can be a permanent solution.

After taking office in 2017, Lam proposed a land reclamation project that would create 1,700 hectares of new land on artificial islands between Hong Kong Island and the eastern waters of Lantau Island over two to three decades. According to the plan, land reserves obtained through reclamation would be used to construct 260,000 to 400,000 residential units for 700,000 to 1.1 million residents, of which 70% would be public housing.

Public opinion is deeply divided over the plan, which would cost the government HK$624 billion (US$80.4 billion.) It would be the most expensive infrastructure project ever in Hong Kong and has faced questions over its environmental impacts.

...as of 2016, about 7,000 hectares of Hong Kong's land was reclaimed from the sea, accounting for a quarter of its developed land area. This land is where about 30% of Hong Kong's people live and 70% of its commercial activities take place.

In December 2020, the Finance Committee of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong approved a HK$550 million pre-study grant for the project. Secretary for Development Michael Wong Wai-lun, who is in charge of land reclamation, said the study was expected to start this month and take about three and a half years to complete. The first stage of reclamation could begin in 2027.

Hong Kong has largely depended on reclamation for land. According to official statistics, as of 2016, about 7,000 hectares of Hong Kong's land was reclaimed from the sea, accounting for a quarter of its developed land area. This land is where about 30% of Hong Kong's people live and 70% of its commercial activities take place.

No matter where new land supply comes from, the key is to keep policy consistent. But that is what Hong Kong lacks, experts said.

"Many policies can only survive the government of the time because the next government will have new policies," said Thomas Lam, executive director and head of valuation and advisory at Knight Frank, a property services agency.

Vested interests

"The sheer size of interest groups in Hong Kong is the root of the problem," said a senior government official. Representatives of various interest groups in the city's land market have constantly blocked efforts to change the status quo through lawsuits or measures to hinder policymaking, the official said.

Property tycoons have deep influence over Hong Kong's political and business arenas, one government source said.

Tactics like filibuster - action designed to prolong debate and delay or prevent a vote on a bill - are often used in Hong Kong's Legislative Council to block decision-making related to housing policies.

For instance, the reclamation project proposed by Lam in 2017 was originally planned to start pre-study in mid-2019. However, the schedule was postponed by two years amid opposition by developers.

The power struggle between the Hong Kong government and the property industry also led to the failure of a long-expected tax program for vacant properties.

Hong Kong depends heavily on property sales for revenue, giving the industry great sway over the city's politics.

In June 2018, the Hong Kong government proposed a new housing policy - levying a vacancy tax on new private residential units - to encourage real estate developers to bring completed residential properties to the market as early as possible. However, the draft was aborted in June 2020. Five months later, the Transport and Housing Bureau announced the revocation of the vacancy tax act. Some government insiders expressed disappointment, citing interference from stakeholders in real estate development.

Hong Kong depends heavily on property sales for revenue, giving the industry great sway over the city's politics. In the 2020-21 fiscal year, Hong Kong's overall fiscal revenue fell 8% to HK$543.5 billion, mainly due to a drop in land revenue, which accounted for 16% of the government's total revenue.

Chan Kim Ching, a scholar studying Hong Kong's land market, said that because land sales are one of the main sources of revenue for the city government, the formulation of housing and land policies on this basis is the crux of the dilemma.

"To ensure high land revenue, the government prevents the housing prices from falling so that real estate developers are willing to pay high prices for land," Chan said. "This creates a vicious circle."

Time for change

"Hong Kong's land problem is a political problem, not an economic one," Ronnie Chichung Chan, president of developer Hang Lung Properties, said at a forum on May 31.

Chan said the shortage of land in Hong Kong is not due to the government's reluctance to sell.

"Who was responsible for Hong Kong's land insufficiency more than two decades ago?" Chan said. "I think politicians should bear the brunt. Every time the government introduced a land policy, it was blocked by opposition politicians in the Legislative Council. It's quite absurd that a small agenda can take more than a year to pass!"

The OHKF recommended that the government accelerate all major land development projects, including new development areas, land rezoning, properties above subway stations and urban renewal, as well as streamlining the administrative procedures for land and housing development.

In March, the central government revised Hong Kong's electoral system, mitigating the Legislative Council's filibuster. The new system expanded the number of Election Committee members from 1,200 to 1,500, representing broad industries. It resumed the Election Committee's function of electing some members of the Legislative Council and increased its role in the nomination of candidates for Legislative Council seats.

Ip said the key to quickly improving the housing situation is to streamline the bureaucratic process of land and housing development. The OHKF recommended that the government accelerate all major land development projects, including new development areas, land rezoning, properties above subway stations and urban renewal, as well as streamlining the administrative procedures for land and housing development.

"Hong Kong's housing problem is so urgent that the HK government has to seize every slim chance," Chan said.

. . . . . .

Hong Kong's 24-Year Housing Crisis

It has been 24 years since Hong Kong's reunification with China in 1997, and housing and land supply have been the common administrative priorities of Hong Kong's five administrations. Although some officials realised the root cause and made attempts to increase the land supply, their efforts were blocked because of intertwined reasons and interests.

In 1997, the first chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa, pledged to build 85,000 new flats every year to meet citizens' housing demands. The campaign led to a quick rise in housing supply. But the Asian financial crisis dampened the city's real estate market and Tung's plan ground to a halt. Land policies were omitted from the government's top agenda for nearly a decade following the crisis.

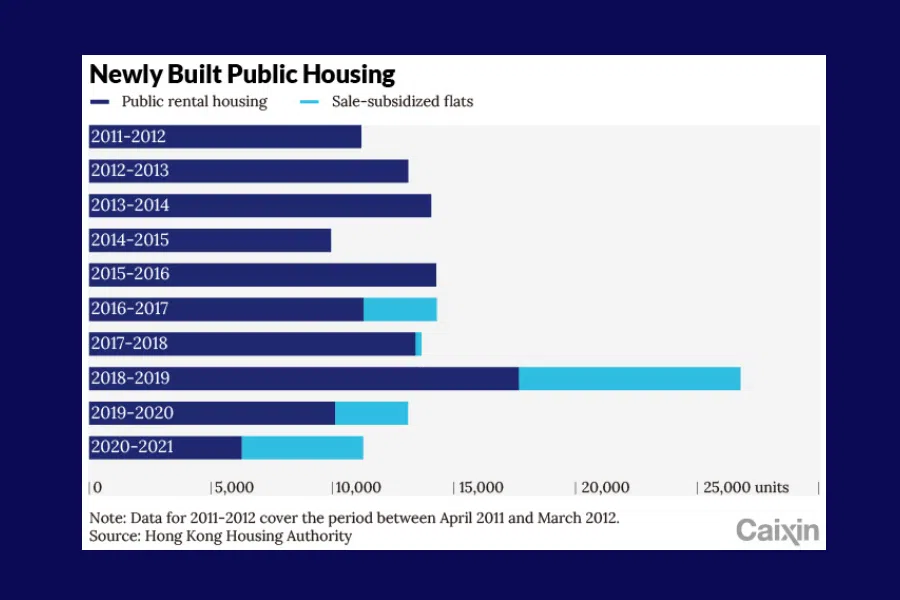

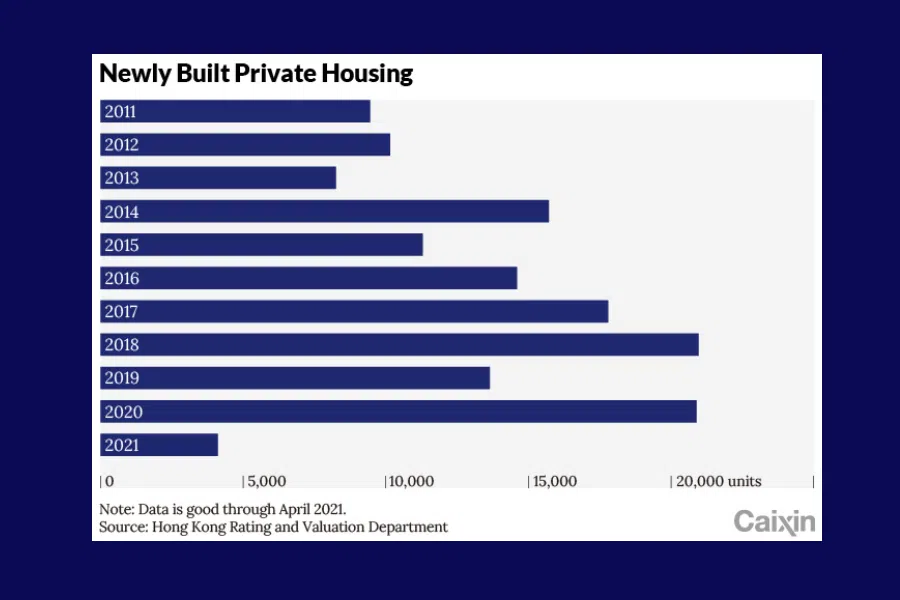

After the 2003 SARS outbreak, Hong Kong's real estate market crashed again. To bolster the market, the government stopped selling land until 2010. During that period, the land supply came to a standstill and the supply of new flats was tight. Construction of subsidized public housing was suspended for eight years. According to official data, from 1995 to 2005, the area of developed land in Hong Kong increased by 6,000 hectares, and from 2005 to 2015, it dropped to 400 hectares, causing a dearth of land resources.

It wasn't until the final years of the tenure of Sir Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, chief executive from 2005 to 2012, that the government revived efforts to increase Hong Kong's land supply to meet public housing demand.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as "In Depth: What's Stopping Hong Kong From Fixing Its Housing Crisis?". Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)