Why Indonesia's Muslim organisations are not critical of China's Xinjiang policy

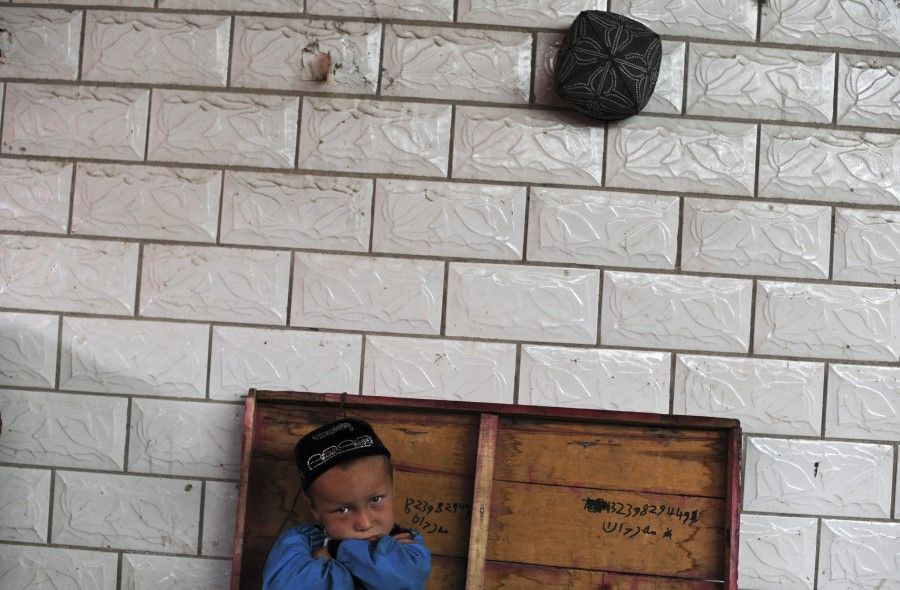

Beijing's reported campaigns of mass detention, political indoctrination and forced assimilation of the Uighurs have attracted the attention of the international community, including Muslims in Indonesia who have condemned China's Xinjiang policy.

The critical view of China's treatment of the Uighurs is especially prevalent among two large Muslim organisations - namely Muhammadiyah and Nahdhatul Ulama (NU).

In December 2018, for instance, Muhammadiyah issued an open letter condemning Beijing's attitudes towards the Uighurs and asked the Chinese government for an explanation. NU has also criticised Beijing's treatment.

China realised that the situation could exacerbate long-held anti-China sentiments in Indonesia and impact its economic interests in the country. It has employed faith diplomacy towards Indonesia's largest Muslim organisations to co-opt their narratives on Xinjiang.

Given the incidence of anti-China sentiment in Indonesia, China should have faced some opposition to its faith diplomacy. Uncannily, however, Beijing's faith diplomacy has gained some traction.

China invited top clerics of NU, Muhammadiyah, and the Council of Ulama Indonesia (MUI) on tours of the Xinjiang camps to witness the conditions of the Uighurs.

China's faith diplomacy began in 2016 during the active implementation of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This has four main components.

The first is framing its Xinjiang policy in the context of terrorism and separatism. In 2018, responding to several protests against China's Xinjiang policy, the Chinese Ambassador to Indonesia, Xiao Qian, visited NU and Muhammadiyah. He informed them of "the real conditions in Xinjiang". During the visit, he framed China's repression against the Uighurs as counter-separatism and counterterrorism efforts, and presented Beijing as an ally of moderate Indonesian Muslims in the fight against a mutual foe.

Secondly, China has also invited these organisations to visit China, including Xinjiang. After Muhammadiyah issued an open letter in February 2019 criticising China's Xinjiang policy, Jakarta kept mum on the issue. China invited top clerics of NU, Muhammadiyah, and the Council of Ulama Indonesia (MUI) on tours of the Xinjiang camps to witness the conditions of the Uighurs.

2019 was not the first time China invited Muslim figures to China. After the Kunming attacks in 2014, the state-backed Chinese Islamic Association invited Islamic scholars from Indonesia and other countries to an Islamic conference in Xinjiang. Similar efforts also occurred in 2016. The attacks saw four Islamic extremists killing 31 people at a Kunming station.

China's faith diplomacy has involved providing scholarships to members of NU and Muhammadiyah to pursue education in China.

The third component is offering donations and collaborating on specific projects. The former has been prevalent method used towards NU, while the latter has been used towards Muhammadiyah. In 2015, the Chinese embassy donated US$7,000 to NU-run orphanages. In 2018, it also funded the building of sanitation facilities in NU-dominated villages in West Java. China has worked with Muhammadiyah on several collaboration projects on education. For example, 32 Muhammadiyah universities across Indonesia have collaborated with Chinese universities.

Lastly, China's faith diplomacy has involved providing scholarships to members of NU and Muhammadiyah to pursue education in China. Some scholarship holders who are NU members have also been co-opted by China. They were invited to Beijing-orchestrated conferences and workshops on Xinjiang and strengthening China-Indonesia relations.

China's efforts at faith-based diplomacy has proven to be fruitful.

Several NU's figures, such as Yahya Cholil Staquf, NU's chairman, have asked Indonesians not to criticise China on the Uighur issue.

Muhammadiyah appeared to be openly critical of China when it alleged that the 2019 visit was choreographed. This position has been confirmed by some Western media - that is, the organisations' representatives were not taken to the "real camps" where the Uighurs were being held and were made to believe that the so-called re-education camps were intended to provide job training and to combat extremism. Although Beijing has denied such claims, organisations such as Human Rights Watch have confirmed that the visit was orchestrated.

Yet, a recent peer-reviewed study reveals that there have been a shifting of views among Muhammadiyah members in their social media activities to show a more positive image of China, including its Xinjiang policy.

Beijing's faith diplomacy also appears to have cast a wider net. There are strong ties between Muslim organisations and the government. These organisations' uncritical view can be one major reason behind Jakarta's silence on the Xinjiang issue. The organisations hold some sway over the government, given the fact many of their members are in the Cabinet.

For example, NU's deputy secretary-general, Masduki Baidlowi has issued a statement arguing that Indonesia's soft approach on the Xinjiang issue is the right way. He is also the spokesperson for the current Vice-President Ma'ruf Amin.

Their relative silence on the Xinjiang issue could also be related to Indonesia's counterterrorism efforts, which these organisations have pledged to support.

There are, however, other factors that may contribute to the success of China's faith diplomacy.

Indonesia's growing economic dependency on China may be one factor. For example, China has through the BRI become Indonesia's second-largest foreign investor. For Muslim organisations in Indonesia, staying silent on the Xinjiang issue serves two purposes: maintaining their ties with the state, which has strong relations with Beijing, and sustaining their own cooperation with China.

Their relative silence on the Xinjiang issue could also be related to Indonesia's counterterrorism efforts, which these organisations have pledged to support. While small in number, there have been Uighurs involved in radical movements in Indonesia.

Finally, there are perceptions in Indonesia that the US, in particular its soft power, is in decline. China has also expanded its media and educational soft-power, which contribute to its image-preserving efforts.

For all its efforts, China's faith diplomacy appears to have achieved the rare feat of walking on water and silenced Indonesian critics of its Xinjiang policy. As long as the Indonesian government sees benefits in its ties with China and maintains relations with these organisations, it is not likely that the latter would turn critical towards China.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.

Related: Is Indonesia's foreign policy tilting towards Beijing? | Huawei digital talent programme: Another source of China's soft power in Indonesia | The ghost of the Communist Party of Indonesia still haunts | Why Beijing offered to help raise the sunken Indonesian submarine Nanggala | Battling atheist China: US highlights Xinjiang issue and religious freedom in Indo-Pacific region