Back to the future: Trade routes from the Silk Road(s) to the BRI corridors

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched by China in 2013 is now ten years old. Also carrying the moniker of the "New Silk Road", the BRI has invoked a reimagination of, or at a least certain throwback connection, to the ancient Silk Road dating back over two millennia.

While this long passage of time from then to now does not warrant drawing any direct line of comparison or continuity, it is intriguing to uncover any legacy that may connect the ancient Silk Road to the BRI in the 21st century. Trade routes stand out as the most salient feature and function of both the ancient Silk Road and the BRI, although they differ a lot in the scope and content of the old vs the new trade routes.

Silk roads through time

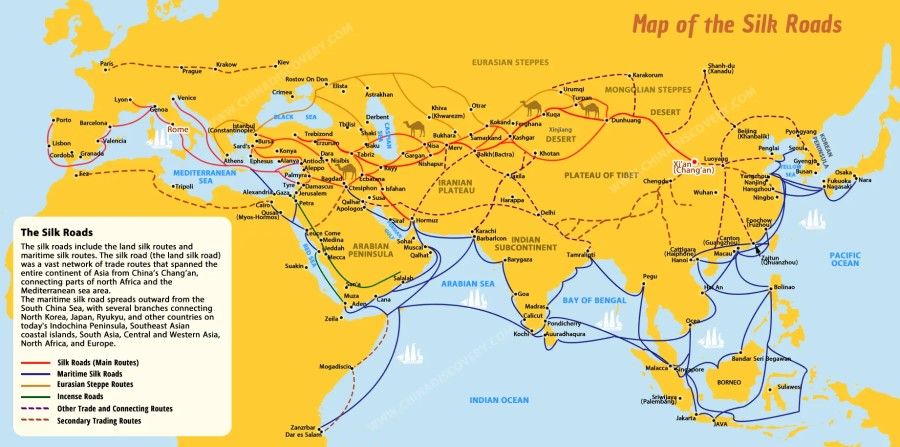

The ancient Silk Road as a single, long and continuous road for trade between the Chinese and the Roman Empires is a largely debunked myth. In historical reality, the Silk Road comprised a set of shorter and more fragmented and mostly overland routes across the Eurasian landmass with secondary or extended routes. While these overland routes originated around 200 BC or earlier, their maritime counterparts did not begin to take shape until at least a full millennium or longer later.

The main section of the Silk Road stretched between the great city of Xi'an (Chang'an) in the east and another historic city Istanbul (Constantinople) in the west (see map 1), as also suggested by the renowned historian Peter Frankopan in his best-selling The Silk Roads: A New History of the World (2015). Frankopan also pointed out that any north-south trading routes were overshadowed by the Silk Roads' east-west directionality.

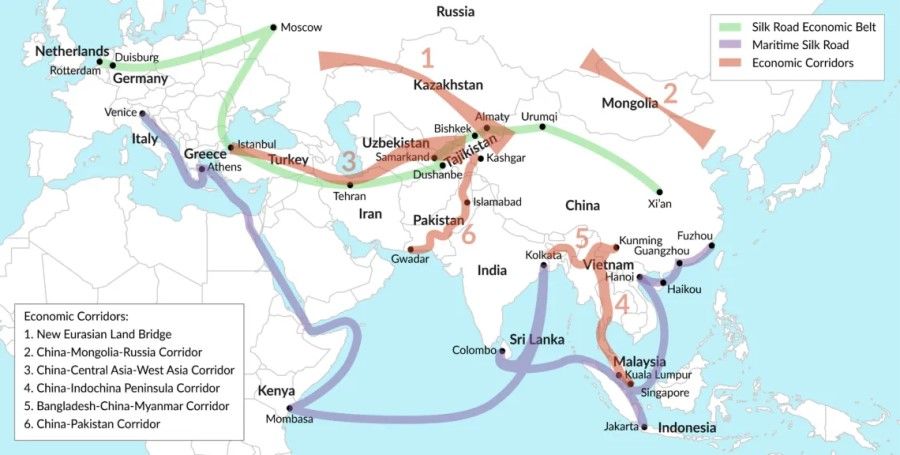

Unlike the ancient Silk Roads, however, the BRI also envisions and drives six cross-border regional corridors that extend from various parts inside of China to neighbouring and faraway countries.

Fast forward to the BRI, the basic geographical length and spread of the Silk Roads have carried forward in the form of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road, respectively. In fact, the latter's historical version was labelled the "Second Silk Road" by the historian of China, Wang Gungwu.

Both modern "Silk Roads" run east-west across Eurasia through cities and regions that largely align with ancient and pre-state cities and towns along the various sections of the Silk Road(s). Unlike the ancient Silk Roads, however, the BRI also envisions and drives six cross-border regional corridors that extend from various parts inside of China to neighbouring and faraway countries.

While these corridors lack precise starting and ending points, they delineate and channel trade routes that have benefited from prioritised infrastructure and logistics projects such as the China-Europe Freight Train routes along Corridors 1, 2, and 3 and the China-Laos Railway along the north-south Corridor 4 (map 2).

Merging the old and the new

To the extent that these corridors approximate some trading routes of the ancient Silk Road, the latter connected small traders and other travellers who would carry and relay short-distance goods between pre-modern cities and oasis towns, a number of which rose to become lively religious and cultural centres like Kars, Kashgar, Merv and Samarkand but faltered later as trade between Tang China and the West declined during AD 850-1200.

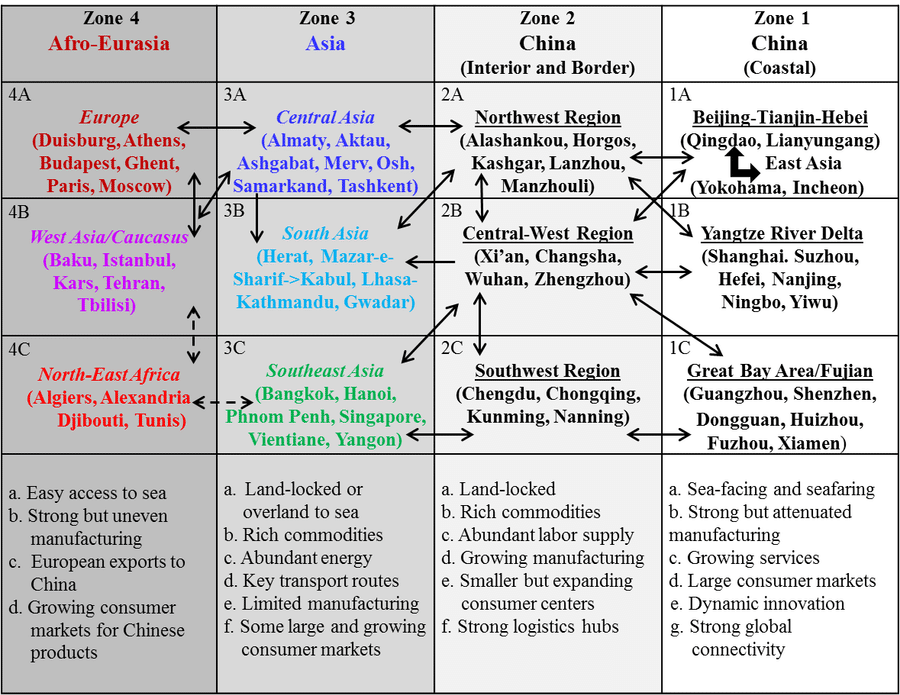

The cross-border freight trains and trucks under the BRI not only brought some of the old Silk Road cities back to linking the new trading paths but also brought in other cities. Together these old and new cities have become nodes of cross-border shipping networks that extend from China's coast to the Atlantic, via both overland routes and land-sea intermodal links (figure 1), even bypassing the cities and territories disrupted by the Ukraine war.

Kashgar has re-emerged from its location as a key Silk Road trading hub, with its century-old bazaar, into a major trading gateway for Xinjiang and also Western China more broadly.

Regarding the resurgence of prominent old Silk Road cities via the BRI-induced cross-border freight trains, Xi'an sent a train of 35 wagons loaded with over 700 tons of walnuts and walnut-processing equipment to Samarkand, Uzbekistan on 18 April 2023. Through Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, the train arrived in eight days covering 4,667 km. The export of famous walnuts grown in a region to Xi'an's southeast reminds us of the trade of fruits and nuts such as figs, hazel nuts, and pistachios between Chang'an and Constantinople along the Silk Road.

On 26 April 2023, the city of Kashgar, China's most western city, launched a trucking service with cargoes of consumer goods and construction equipment to Samarkand under the United Nations Convention on Road Traffic. As a nodal city for the BRI's Corridor 3 (map 2), Kashgar has re-emerged from its location as a key Silk Road trading hub, with its century-old bazaar, into a major trading gateway for Xinjiang and also Western China more broadly.

In the first quarter of 2023, Kashgar's international trade amounted to over US$2 billion, which grew 102.3% over the corresponding period of 2022 affected by the zero-Covid policy, ranking second in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region behind only Urumqi.

Trade an indelible bond

These re-established trade ties also cover long distances by more connected and faster rail and road shipping routes. While goods moved at about 40 km a day along the ancient Silk Roads, the China-Europe freight train runs an average of 40 km an hour across Eurasia. Like the Silk Road merchants who had to halt at caravanserais to rest their camels, the freight trains today need to change drivers and gauges at international border crossings.

The ancient Silk Road extended approximately 6,400 km, whereas the "Great Bay Express" freight train runs from the Chinese southern city of Shenzhen (1C) to Duisburg, Germany (4A), via the subzones of 2B, 2A, and 3A, covering a journey of over 13,400 km (figure 1).

Launched in 2020, 48 "Great Bay Express" trains loaded with 34,300 tons of cargo ran from southern China to Europe in the first quarter of 2023, 77.8% and 150% more than the first quarter of 2022 when China was still under the zero-Covid regime.

Faster movement over much longer distances aside, the Bactrian camels ploughing the Taklamakan desert along the ancient Silk Road form half of the logo, next to a galloping train, for the "Chang'an Express" that runs from Xi'an to a score of Central Asian and European cities and back. The camel bells along the old Silk Road seem to echo with the roaring BRI freight trains today.

More importantly, the once-prosperous but lost Silk Road cities have made a strong comeback as trading hubs while new cities have risen recently as logistics centres for cross-border freight trains under the BRI.

Trade is what bonded the segmented routes for slow-moving caravans along the ancient Silk Roads and binds much longer and more complex freight train routes today. The multimodal shipping between land and sea, which was impossible at Silk Road times, has lengthened and tightened trade networks between East Asia and North-East Africa through Central Asia and Western Europe (figure 1). More importantly, the once-prosperous but lost Silk Road cities have made a strong comeback as trading hubs while new cities have risen recently as logistics centres for cross-border freight trains under the BRI. From the Silk Road to the BRI, the past continues to be part of the present and future.