Wang Gungwu: China, ASEAN and the new Maritime Silk Road

Professor Wang Gungwu was a keynote speaker at the webinar titled "The New Maritime Silk Road: China and ASEAN" organised by the Academy of Professors Malaysia. He reminds us that a sense of region was never a given for Southeast Asia; trade tied different peoples from land and sea together but it was really the former imperial masters and the US who made the region "real". Western powers have remained interested in Southeast Asia through the years, as they had created the Southeast Asia concept and even ASEAN. On the other hand, China was never very much interested in the seas or countries to its south; this was until it realised during the Cold War that Southeast Asia and ASEAN had agency and could help China balance its needs in the maritime sphere amid the US's persistent dominance. The Belt and Road Initiative reflects China's worldview and the way it is maintaining its global networks to survive and thrive in a new era. This is an edited transcript of Professor Wang's speech.

I started life at the University of Malaya with my first project on the Nanhai trade, which is about China's trade in the South China Sea. But I won't concentrate on the past because although I am here as a historian, the word that leads me to change my focus is the word "new" that you put into the title "The New Maritime Silk Road".

My talk is not just about a new route; there are many new factors at play. ASEAN in the title is new, very new. China in this context is also new. The new China is quite different in many ways from the old China. So the word "new" applies to all three.

The subject covers such a large area that I think it would be helpful to take them in parts.

The struggle to make Southeast Asia a region

I will begin with ASEAN in the context of Southeast Asia as a region. What is this region? Because that is, to me, central to the whole story. And China, this new China, is a great power again, after about 200 years when it was very weak and divided. We will talk about China rising, which is new. That would be the second part of what I'm going to talk about. And finally, I will come back to the newness of the Maritime Silk Route.

So let me begin with ASEAN.

ASEAN actually refers to Southeast Asia, and the two names are often taken together. But I think we should be very clear that they are very different in many ways. And when we talk about Southeast Asia, we all know which are the countries we refer to. But what is the most interesting thing about this region is that for thousands of years while the region has been there, it never had one single identity. It never had one single name. This is itself such an intriguing question that many historians have spent their careers and lives trying to figure it out.

Looking at the terrains, the lands that they [the former colonial masters] were about to leave, and when they saw themselves having to leave, how would they maintain any influence in that area? That's the starting point. So they named it "Southeast Asia".

First of all, to what extent was it a region? And to the extent that it was a region, why did it never have a single name that they all commonly adopted? So that in itself raises a lot of questions which affect its present as well. So that gives me my historical background to Southeast Asia.

ASEAN is so new - we date from 1967. Some people may say we date it from 1999, when all ten countries became members of ASEAN.

But, to go back a little, "Southeast Asia" itself has a name. It was sometime during the middle of the Second World War that the term was used, essentially by strategists for the former empires. Looking at the terrains, the lands that they were about to leave, and when they saw themselves having to leave, how would they maintain any influence in that area? That's the starting point. So they named it "Southeast Asia".

Having given it a name, books were written. And since then, of course, we've had hundreds of books, thousands of articles written about this area called "Southeast Asia". So we've now accepted the name. But if you go through all those articles, you'll see, again and again, references to the question "Why did it not have an identity before?". Why was it so difficult to see it as a region prior to 1945 or after 1945?

Distinct identities: peoples from the land and sea

And so, it requires us to look back to how it all began.

When you look at it this way, from the very beginning it was quite clear that the sea was different from the land. Different peoples, who had devised different cultures of their own, were creating different kinds of states and absorbing different religions. And, in fact, living lives which were, in many ways, quite distinct from one another. But today we take them all as a region. But we have to go back to recall what it was like, to begin with. We do realise that, right from the beginning, there were people indigenous to the region who were different on the continent - roughly the areas between Vietnam and Burma down to Thailand - and the ocean. These were very different people. Right from the beginning.

But from the time we had records, we could see that these differences were accentuated by the fact that the people actually came from different directions. The people on land came down river valleys from the north - from almost the middle of Central Asia. Coming down the river valleys into the Salween, the Irrawaddy, the Mae Nam Nan, down the Mekong, and to some extent also including the Red River of northern Vietnam. And they were very different peoples, very different from the indigenous people who were found there.

The indigenous people, we recognise them through their languages today. What they had in common was a Mon-Khmer Austroasiatic language from which we derive today's languages of Vietnam and Cambodia, and the Mon language in Myanmar.

And then we had a different lot of people coming, bringing with them different cultures, different languages and different systems of governance among themselves. And we had people who essentially spoke Tibeto-Burman languages and people who were what are now recognised as Thai, whose languages were half-related to the Sino-Tibetan family of languages, coming from the north down the river valleys. Now, this is one lot of people. And they remained more or less settled in their river valleys. And they did not really turn to the sea except parts of the Khmer empire.

But at sea, people were also coming from the north, from south China, southwest China, and turning to the sea via Taiwan, via the Philippines, via the coast of Vietnam, down to the archipelago. People whom we now identify, more or less via their languages that have a common origin, as the Malayan-Polynesian peoples who spread amazingly halfway around the world, all the way to Hawaii and the Easter Islands at one end, and the other end to Madagascar and the African coast.

These extraordinarily mobile maritime people were committed right from the beginning to the sea and never really went into the interior, but very comfortable at the river mouths which they controlled. And they lived by the sea, and lived on what the sea could produce for them, including the trade and all the relationships which could easily be brought together because the sea was very open; you could move things easily along, unlike on land where the river valleys especially, with lots of highlands, uplands, mountains in between, restricted relationships.

So, right from the beginning, they were so different. At least, that is one reason why nobody quite saw them as part of one region. So you can see what a struggle it was for several generations of historians since the 1950s. They were trying to see Southeast Asia as a region. But to the extent that they have succeeded - and this is something we'll come back to - this is itself very important.

Trade boosted interlinkages and connections

The historians showed that through that time, as trade grew gradually, as the people who were involved in the trade were interconnecting with one another, those who came from the west, from the subcontinent of India, further west from Persia and the Arab world, trading across the Indian Ocean to Suvarnabhumi, the "Land of Gold", and so on, on the one hand; and others reaching out to China because China was already known to be a united powerful state, one of the richest in the world from very early on, and therefore attracting merchants from all over - overland as well as maritime. And that trade gave a tremendous focus for the peoples of the maritime coasts. This maritime area was where all these maritime peoples performed a major central role to keep the trade going -that was how it all began.

And because that trade developed, on the one hand, the people from the west - the Indians, the Hindu Buddhists, and later on the Muslims from Persia and the Arab world - had added a tremendous amount of activity to this trade and extended it to China and Eastern Asia; on the other hand, the Chinese were taking an interest. But bear in mind that the Chinese were never fully interested in the south. China was a northern continental power.

And the Chinese, on the other hand, did not transmit ideas and values so much as they were trading.

With that background, it is no wonder that nobody seriously thought about Southeast Asia as a region. This was an area of openness. Trade was free. Religious ideas, ideas about politics, ideas about life, philosophy, architecture, art, music, and dance were transmitted very readily, particularly from the west. First from the South Asian continent, the Indian subcontinent, and then later on from further west, from the Middle East in general.

And the Chinese, on the other hand, did not transmit ideas and values so much as they were trading. Economic activities grew steadily, and about a thousand years ago it became a serious occupation for the merchants of southern China. But just to add a footnote here: this was only among the merchants. The state itself, the Chinese imperial state itself, took relatively little interest in this part of the world compared to the others. Now that is the background before the coming of the Europeans.

What the historians have managed to show in the last few decades was that, during that period just before the arrival of the Europeans, the region was taking shape because they were sharing that trade that was growing steadily, largely led by Muslim traders from the Middle East and the Chinese traders coming from southern China, particularly the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong.

Those two provinces plus the Middle East, via South India, made this trade a flourishing trade for the peoples who lived in this area. The maritime world, which we can now say, was a kind of Malay world - using "Malay" in the broadest possible sense - of Nusantara right across from Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula to the Philippines and beyond. So that role was already being very well developed prior to the arrival of the Portuguese.

Arrival of the Europeans

The arrival of the Europeans did not change the picture. The Europeans added one more set of actors, whether they were Portuguese, Spanish, or later Dutch, and finally the English. They added some more actors, but the pattern of trade, the way the trade was conducted, the way the Chinese and Muslim traders continued to play key roles in that spread of Western influence and Western commercial interest in the area, that part did not fundamentally change. It simply was expanded, intensified, and now involved these foreign merchants with powerful ships.

The new factor was that the Europeans knew how to fight at sea in more sophisticated and technologically advanced ways than anybody else in the region. And gradually, after about 150 years or so, that naval advantage gave them a kind of dominance, the beginnings of a hegemonic position. Naval power began to dominate the area. And what it meant essentially was that whoever had naval power could actually dominate that trade. Trade was no longer in the hands purely of simple merchants seeking profit, but of merchants who also had a mission, whether it was a Christian mission by the Portuguese and the Spanish or the well-organised economic mission of the Dutch East India company.

And finally, with the development of industrial capitalism in England and France, there was the coming of industrial capitalists who used different kinds of funding, and there were different kinds of state involvement. And the scale and intensity of that trade grew. But you can see there was no fundamental change until industrial capitalism completely changed the nature of economic production. And the new forces of this production transformed the way that trade was conducted. Markets were found. New resources were transported long distances to enable the industrial capitalists to gain even further advantages.

And the greatest wars fought among the navies were not between the Europeans and the Asians. The greatest wars were actually fought amongst themselves, whether it was the Dutch against the Portuguese, against the Spanish, or the Dutch against the English.

Naval power the turning point

So you can see that the turning point was naval power. And I don't mean just mercantile ships. This is naval power. Ships that are able to fight at sea and win their wars at sea. And the greatest wars fought among the navies were not between the Europeans and the Asians. The greatest wars were actually fought amongst themselves, whether it was the Dutch against the Portuguese, against the Spanish, or the Dutch against the English.

And finally, the most important one, the decisive battles which gave the British complete superiority at sea when they defeated the French in the Indian Ocean. At that point, the two industrial powers of England and France had their final competition in the Indian Ocean, and the British won and took over control of the Indian Ocean; by that time, of course, from the other side, the Americans had already pushed through to the Pacific. So we see the beginnings of an Anglo-American partnership in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

In fact, it was the British Navy that controlled everything. The Americans played, at that point, something of a supporting role for the British Navy. But that changed from the late 19th century down to the First World War.

And even then, it was interesting that nobody could agree on a single name for this region. That itself is to me, as a historian, very intriguing. There was still no agreement on a single name. Different names were used. For the maritime world, some called it Malaisie, and for the mainland, Indochina was used because those areas were just between India and China on the continent.

Eventually, the Japanese joined in, and the Chinese traders became partners with some of the European enterprises. They took advantage of opportunities for them to advance their interests. More and more Chinese merchants became involved, and they developed more and more interests. Therefore new terms arose both in China and Japan: Nan'yo for the Japanese and Nanyang for the Chinese. Both meant the same, meaning "the Southern Ocean".

For the first time, a common name appeared. But they were really invented for the maritime states, for all those whose ports faced the South China Sea or the East Java Sea or the Indian Ocean. The name did not really cover the overland northern parts of what we call Southeast Asia today. But then this one common name led ultimately - to cut the long story short - to the Japanese challenging Western dominance in this part of the world.

...it was Japan that showed that the whole of Southeast Asia could be ruled by one empire. One power could control all of it. And they did.

Japan asserting its dominance

The Japanese had learned from the West; they learned it too well. They shared some of their ambitions, but they also took on the idea that Asia should be for the Asians. There was this idea of an Asianism which was superior to that of the materialistic capitalists from the West. Asians had a spiritual civilisation which should be supported, and we should drive these Europeans out of Asia.

So Japan led something which quite a few other Asian leaders also sympathised with, that is, that they should really get the Europeans out of this part of the world, and the Asians can look after themselves thereafter. Except the Japanese went too far, went too fast, and whether they were sincere about really leaving Asia to the Asians or whether it was Asia for the Japanese - that was another matter. That led them to start a war that they couldn't win. And that ended their story. Nan'yo is no longer used in that context.

But what they did do - and this is the part that we often forget - it was Japan that showed that the whole of Southeast Asia could be ruled by one empire. One power could control all of it. And they did. In fact, if you look around, all the ten members of ASEAN today were directly or indirectly under Japanese administration - in some cases military administration, in other more civilian, but nevertheless, under Japanese administration for at least three years, if not three and a half years. And during that time, there was fighting on the Burma front and fighting off the coast of the Philippines at sea.

What became clear was that the Japanese actually saw a region. Of course, they linked it up with the East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere - we didn't quite recognise it as such - but actually, Japan looked at Southeast Asia as one region controlled from the headquarters in Taiwan. In fact, the governor-general's office in Taipei under the Japanese was actually the headquarters of the parts of Southeast Asia that the Japanese controlled. But they failed. The war ended and they lost everything.

It was exactly during that time that the imperialists knew that after the war things would be different, and they predicted that, they foresaw it. The British strategists, the great imperialists of its day, began to look for ways and means of retaining their influence after they were forced to go home and decolonise and let the new nations establish themselves, which they saw eventually they would have to do, particularly when they saw they had to leave India. The British were realistic enough to see that. And they used the name which they had used in a purely military context - the "Southeast Asia Command".

China and India would be forces to reckon with

By that time, it was clear that China, as an ally of the allied groups against Japan, was emerging as the new power. This was Nationalist China under Chiang Kai-shek, not Communist China. Chiang Kai-shek had met Churchill and Roosevelt in Cairo as equals. And they were going to take over this part of the world once they defeated the Japanese. That was also obvious. So the British saw that a rising Nationalist China was going to be a power to reckon with. And if they left India - of course they didn't know then that they would partition India - but if they left India, British India in the hands of Indian nationalists would be a power in the future.

So, along that strategic line of thinking, it was quite clear that in the future, if they wanted to have any influence in their former territories, they would have to watch out for these two Asian powers: China to the north and India to the west. And they needed somehow to ensure that this region could be defended in order to protect their interests there. And the name "Southeast Asia" emerged as the favoured name.

I would almost call it a post-imperial mission to make this region "real". The people within the region were not conscious of it, and did not actually see this as urgent because they had their own problems of nation-building.

It was still not clearly defined because, as some of you would remember, when Professor D.G.E. Hall wrote his History of Southeast Asia, he did not include the Philippines because the Philippines wasn't a part of the Southeast Asian Command led by the British. The Philippines was part of the Pacific Command led by the Americans. But eventually both the British and the Americans, when they saw that decolonisation was inevitable, recognised that they should look at the whole region together, and the Philippines was added, and Southeast Asia became, potentially, the ten countries that we have today. So that was done, the countries were geographically marked out, and the maps began to show this. Until then, there was no such map where you actually saw this region.

Post-imperial mission to make Southeast Asia 'real'

From then onwards, I would almost call it a post-imperial mission to make this region "real". The people within the region were not conscious of it, and did not actually see this as urgent because they had their own problems of nation-building. That was much more urgent, much more important to them. And they devoted all their energies to building up the new nations that they had taken over as colonial states or revolutionary states. Indonesia and Vietnam were revolutionary states. As they were trying to build their nations, they weren't thinking of the region.

So the only people who seriously thought about the region were people from outside, particularly the British strategists, in liaison with the Americans, the French and others, who all came to realise that this was the one way they could protect their interests in a region outside of China and India - the future Asian powers. This was pretty good strategic thinking. I mean, you look back and these people had imagination and had a long view. It's a mistake to think that Westerners only have a short-term view and that only the Asians and Chinese are long-view people.

There were great strategists in the West, particularly among the British - the Europeans were much better than the Americans there - and their long view was that this area had to be separated or separately considered and protected, where their interests were concerned, from being dominated by either India or China, or both. And Britain had a special interest because it also had possessions or dominions in Australia and New Zealand. So this was part of their extensive naval and global maritime empire.

They had extra reasons. But so did the Americans. They were also interested in East Asia generally and the Pacific area. Therefore the two combined in deciding that Southeast Asia would be a focus of regional development, and to make this into a region they could defend.

Southeast Asia's evolving identity during the Cold War

So when we talk about ASEAN today, we recognise that, with the Cold War, it was not possible to see the region as one. Almost straight away from day one, when the Cold War came to Asia, Southeast Asia was divided. Let me list the three most critical events that shaped what we call ASEAN and what is Southeast Asia today, or at least the beginnings of it.

The first was the fact that Indonesia turned capitalist under Suharto, destroying the Sukarno heritage, destroying the Communist Party of Indonesia totally, and then realigned with the capitalist camp. And the other four members who joined Indonesia to become ASEAN were forced to take sides under those conditions. The Cold War was becoming very fierce, very intense, particularly on the mainland in Indochina where there were the beginnings of the Vietnam War. The region was divided and half of it became aligned to one side. The other half was a little bit more mixed, but nevertheless, the half that was aligned was a source of a new Southeast Asian regionalism. Now only half the region was ASEAN. I would call it "ASEAN One" - five countries very clearly aligned to one side in the Cold War.

The second event was the recognition of the People's Republic of China (PRC). You recall that when the Kuomintang fell and the communists took over, China was left out of a lot of things, particularly by the allied forces in the Cold War. China was not a member of the United Nations and so on. But soon after the overthrow of Sukarno, forces of the left began to recognise the need to put the PRC in place of the Republic of China that merely controlled the island of Taiwan.

This movement had been going on for some time, but it finally succeeded in the early 1970s. It allowed Nixon to go to China, and it allowed the Americans to help China escape from being dominated by Soviet Russia. So in a way it completely changed the shape of the Cold War itself. It pulled China out from under the Soviet umbrella, and that created new conditions for the region to survive, to take on a different life, with a different role for China.

But the third event, which was even more surprising to most of us, was the defeat of the United States in Vietnam. The US and its allies were forced out of Vietnam. Now, when that happened, there was a lot of uncertainty as to what would follow. But what was clear was that, for the next 20 or 30 years, that half ASEAN of five members, with Brunei joining later, that half ASEAN began to find that it could have agency. It was not just a pawn or a puppet of one side in the Cold War. It could have agency because it could also turn to China.

You would recall that countries like Malaysia, and eventually the Philippines and Thailand, actually recognised the PRC during that period. The only country that refused to do it was Indonesia because of the Communist Party of Indonesia. And Singapore just wanted to be on the safe side and waited for Indonesia. But three out of the five actually established diplomatic relations with China. And that indicated it had some agency. And that encouraged them to develop an ASEAN that could have greater autonomy and not to be aligned to one side or the other.

Then came the Indochina wars between Vietnam and Cambodia. Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia, destruction of Pol Pot's group of Khmer Rouge, and then the recreation of the new states of Laos and Cambodia as separate and independent of Vietnam, with ASEAN - at least those five countries - playing a role, joining the United States and China, in playing a role in determining the fate of Cambodia. All that led to two very important things: one was that it confirmed that ASEAN could have agency if it played its cards right, if it stuck together, and that it could work out some strategy to maintain its autonomy in that region.

This was the real ASEAN of ten countries completely reframing themselves as an autonomous body, a region that could exercise agency, determine its own fate, and find its own position in between great powers, whoever they may be.

A real ASEAN and China

And it worked. The net result was, to everyone's surprise, a real ASEAN. All ten members joined ASEAN by the 1990s, with Cambodia right at the end in 1999. It was now "ASEAN Two". This was the real ASEAN of ten countries completely reframing themselves as an autonomous body, a region that could exercise agency, determine its own fate, and find its own position in between great powers, whoever they may be. Towards all those powers in the north, south, west and east... the ten countries could have some room to manoeuvre. And that, I think, was a great start.

Now, in that context, a new China was emerging. Another new thing was that China now saw an ASEAN with agency. That meant that China no longer saw ASEAN as a creature of the West - anti-communist, and just determined to be anti-China - as they once did. Instead, they saw an autonomous region with agency that the Chinese could now help to bring closer to themselves, and show that they are actually in support of and totally in sympathy with this autonomous region of Southeast Asia.

And you'll recall how when China joined the WTO, how much effort it put into befriending ASEAN and accepting ASEAN's invitation to form ASEAN+3, ASEAN+1, and all the open efforts to include more people in the larger region so that the region of Southeast Asia would have a bigger role to play, a bigger playground to play in, a bigger arena to be active in.

And that was a very successful period for ASEAN. You remember the days of the ASEAN Charter, when there were tremendous expectations of ASEAN to do this or do that. And many of the foreign offices of the ten countries were genuinely hoping that this would end up becoming a body that could really act together very effectively and play a role in regional and world affairs. I think I leave it at that to say that that was the new ASEAN.

And this was new for China. This was an opportunity which it never had before, never thought of before. Because if you go back to Chinese history, what was so new to China was that it looked south for the first time seriously. Prior to that, the Chinese arrived at the coast of China, the South China Sea, and they stopped. They conquered parts of north Vietnam, which is now independent, but at that time, for nearly a thousand years, it was a protectorate of the Chinese, before it finally got its independence. But the Chinese actually never moved south.

All their problems were in the north. All their enemies, all the threats. And we know that if you look at all of Chinese history, almost 90% of the material is about north China. I would say right down to modern times. Almost 90% of all the material is to do with northern China and its problems from Central Asia and Northern Asia. Very little about the south, largely for the simple reason the Chinese found no enemies out there. There were relatively small countries interested in trade, providing a major trading route with the Indian Ocean states. Everybody was more or less satisfied with the conditions there. There were no great navies threatening anybody, nobody was changing the map in any way that was threatening to China, so China took less and less notice over time. In fact, they did not pay much attention really, in my view, until they were forced to when they were half conquered, When most of north China had been taken over by northern invaders.

The Song dynasty was driven to the south, and the Southern Song, out of economic necessity, had to depend on encouraging trade with Southeast Asia to survive economically so the taxes on the merchants could be part of the regular revenue of the state. And then they began to take notice of the south. So roughly a thousand years ago, when the Song dynasty was under threat from the north, more and more of the merchants in Fujian and Guangdong were encouraged to trade. And that developed gradually into a very active trade in which the Muslims, particularly the Muslims from the Middle East, and the Chinese developed a very close relationship, not always friendly - they were rivals, competitors, and so on - but it was a very rich relationship over centuries. That went along very well and reached a climax when the Mongols conquered China, all of China. And the whole of south China was taken by the Mongols.

But the Mongol interest was a totally different one. They even used the Chinese Navy and, with the help of the Koreans as well, to try and attack Japan. That's the kind of Mongol mind - that whatever there was, they ought to take it.

Now, the difference was this: the Mongol conquerors made a big difference to the story in China. Because for the first time since the Mongols came from the north and conquered China from the north, the north was not a problem, and the Mongols were interested in the south, that is, how far they could go further south.

And when they found that the Chinese had a navy, the Song Navy, which was not developed to fight against the south, but to defend itself against the north, the Mongols took over the Chinese Navy, got the Chinese sailors to help them to go to Java, and to Champa on the Vietnam coast. And they were actually actively using the Chinese Navy for the purpose that the Chinese never intended. And that itself is very interesting.

But the Mongol interest was a totally different one. They even used the Chinese Navy and, with the help of the Koreans as well, to try and attack Japan. That's the kind of Mongol mind - that whatever there was, they ought to take it. A different world view had come in, that changed the picture a great deal.

Admiral Zheng He's voyage and influence of the Mongols

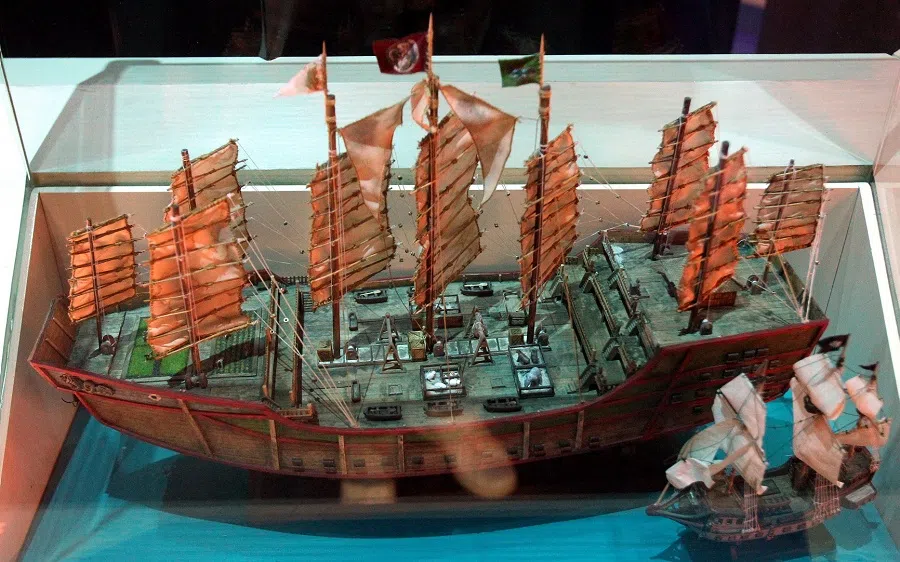

As for the Chinese Navy under Admiral Zheng He going south and going to the Indian Ocean - that was not something initiated by the Chinese. I would say that had been made possible, and even imaginable, by the fact that the Mongols had created a regular, very active relationship with the Middle East, with the Mongols expanding overland to the Middle East. The Mongols were reaching out to their own people on the other side, in the Persian Gulf. And so, when the Ming took over from the Mongols after getting rid of them, the Ming inherited that connection. And the Yongle emperor, who was dealing with the Mongols in the north, took over the Mongol role to find out what was happening in the Mongol empire in the Middle East, and he sent Zheng He out to find out. So this was all related.

The net result was at the end of it all, after seven voyages, with the eighth they decided that it was not worth it. All that expense; there were no enemies out there! And if there were no enemies out there, why all this expense keeping up this navy? For what purpose? Nothing to gain. Leave it to the merchants, if at all, leave it to the foreign merchants.

In fact, the Ming dynasty actually took on a policy which became very hurtful to its future, without knowing it. And that was that it banned maritime trade for Chinese merchants. Because of Zheng He, people think of the Ming as a time when the Ming empire expanded its naval influence everywhere. Not at all. They stopped the navy, destroyed the ships, and limited foreign trade to foreigners coming to China. And not allowing the Chinese merchants to go out to trade. They could trade with the foreigners arriving in China, but they could not go out to trade. And all that trade was then left in the hands of a tributary system, which they refined and bureaucratised, institutionalising it into something very elaborate, to control and guide the trade.

The Opium War, and the opening of China transformed the Chinese. For the first time, they were defeated at sea, and the country was endangered from the sea. There were enemies out at sea. And that was a complete shock to the Chinese.

China's changing attitude towards the sea

Therefore, when the Europeans arrived, the Chinese were nowhere to be seen except as private merchants travelling all over the place who were very active but without naval power or backing from the state. In fact, they had no recognition by the state. In many ways, some of those merchants were illegally trading outside. And once they went out there illegally, they couldn't even go back to China without endangering their lives.

So that was the situation in which the Europeans were able to move themselves into the system together with Muslim traders, Chinese traders, Indian traders, indigenous Southeast Asian Malay, Burmese, Thai, and other traders, and gradually building their influence until they became the dominant force. And the Chinese paid no attention until it was too late.

The Opium War, and the opening of China transformed the Chinese. For the first time, they were defeated at sea, and the country was endangered from the sea. There were enemies out at sea. And that was a complete shock to the Chinese. They didn't really take it seriously to begin with. But by the end of the 19th century, it was quite clear that the lack of a navy was absolutely crucial. It was, in fact, threatening its very existence. The Japanese navy, trained by the British, were able to destroy what was left of the Chinese navy in just one set of wars. Thereafter, the Chinese navy disappeared for a whole century. There was no serious talk about the Chinese navy until the 1990s.

Yet, at the same time, for China, when it was under the late Manchu period, or when they were nationalists or communists, they were all aware that the sea was no longer a peaceful place. The sea was a threat. Foreign navies could attack China, and China was vulnerable. That changed their world view. This is a revolutionary change. Because for thousands of years, they've never had an enemy. For the first time, they had an enemy. So they started to rethink that. But it took them a long time to get going. They had to unite their country, they had to restructure their whole modernisation programme, try democracy, liberal capitalism... they tried communism... none of these satisfied them.

And it was all a mess until Deng Xiaoping's reforms began to converge all these new factors together. A mixture of capitalism, socialism and a recognition of the new economic dynamism that the global market economy represented. And they joined in. And they joined in, to the extent of inviting themselves, and was accepted by the WTO.

They saw that the changes from ASEAN One to ASEAN Two was an opportunity for them to help them get into the heart of maritime trade, which had become more and more vital to their economic development. By the turn of the century, by 2000, it was very obvious that the Chinese economy was now dependent on maritime trade. Not just helping the Chinese, but was crucial to them. It was an existential problem that they should control their own seas to ensure that their maritime trade was protected.

The serious consideration about naval power finally began to take shape because now they had the money to build their ships. Prior to the 1990s, the Chinese were so poor they didn't even have the resources to do that. But from the 1990s onwards, they were determined. And you can see what happens when the Chinese are determined to do something. They can be extraordinarily efficient, and, within a few decades, people are talking about the Chinese navy as if it was a major threat to the world and all that, which is, to me, absolute nonsense.

...all they can hope for is to make sure that they are themselves totally defensible at sea, and their economic dependence on maritime trade could not be threatened, blockaded, or totally contained by forces hostile to China's development. That's the Chinese approach.

The Chinese are building up a lot of ships and supporting forces, but they still have not fought a naval war. As far as I can tell, they've never really won a serious naval battle in the whole of their history. So I would put a question mark there about China being a naval power. But nevertheless, they are trying. They're building it because they want to make sure that their coasts are safe, that China can never be threatened or invaded by sea again, and that their maritime routes for their trading needs and so on would be protected in the future.

Now these are their ambitions. Have they more ambitions beyond that? One cannot be sure. All I can say is, at this stage, all they can hope for is to make sure that they are themselves totally defensible at sea, and their economic dependence on maritime trade could not be threatened, blockaded, or totally contained by forces hostile to China's development. That's the Chinese approach.

The new Maritime Silk Route

Now, finally, to the new maritime route.

We do recognise it as new because the old one was very different. The old one, as I said earlier on, we recognise it as very peaceful. It didn't involve that many people because travelling by sea, long-distance trade, was still a pretty precarious business. And on the whole, volumes were small, ships were small, and many ships were sunk, lost at sea. It was dangerous. The number of ships involved were relatively small by modern standards.

The situation didn't really change until after the 18th century. And particularly, once we talk about the global market economy, once the Suez Canal shortened the route between the developed northwestern European industrial economies and the Atlantic United States economy, once you shorten that route into the Indian Ocean on one side, and with the Americans on the other side with the Panama Canal and so on open to the Pacific, when all these oceans are open to global domination by a really powerful navy, the world really changed. That is globalisation reaching its heights that've never been achieved before. Some people talked about globalisation before modern times, but that was only by land. And that was very limited.

Genuine globalisation can only be achieved by sea. Then the whole world can come under control. And that had started with the British and taken over the Americans. Now it is quite clear that the Americans and the British still recognise that this kind of maritime dominance is vital to their interests. This is what made them powerful, made them what they are, put them in a position to tell the world how to be modern, how to accept universal values that they had devised and worked out, and how to recognise that this is the way to go in the future. There's no other alternative but to go this way. And anybody trying to do it differently are getting it all wrong. These are the messages that we have been getting, I would say, since the end of the Second World War. And it was led by the Americans.

Now, this is the global maritime world dominated by the most powerful navies of the world. China wants to find a role in it.

But never forget that British naval power was always in the background. This was something that the Americans inherited and made much stronger and much safer because the Americans, unlike the British who were constrained by the fact that they were an island off a continent, had their own continent. They have no enemies on their continent - no land enemies, nobody to threaten the United States itself - so that they could concentrate almost all their resources on building a navy that can control the world, beginning with the two oceans, Pacific and Atlantic, and since the war in the Middle East, also the Indian Ocean. This is global naval hegemony at its strongest. It was something that the British dreamt of but never quite had the power to achieve. The Americans have achieved it.

Now, this is the global maritime world dominated by the most powerful navies of the world. China wants to find a role in it. A Maritime Silk Route is one of the many ways of talking about it. But if we look closely at it, what's new about it is that this new maritime route depends on other people's power. The people who can actually control and police this global maritime economy are not an international community - it is Anglo-Saxon naval hegemony. And the Chinese certainly identify that as something that's very very powerful, very difficult to deal with. And I think the wise leaders amongst them would never think of actually challenging that. Because that is really too tough.

What the Chinese want to be sure of is that in their own neighbourhood, in their own backyard, they must have enough naval power to ensure their country's safety. Because they still, after all, have continental problems. They've got 14 different neighbouring states on land. All have to be delicately handled, and some of them are hostile. So they have enough problems of their own. Naval safety or naval influence is only one part of what they need. I think the Chinese recognise that.

Remember at the end of the Cold War, one of the first things they did to show their understanding of their continental needs, was to set up the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). The recognition that they had to safeguard their continental borders at the end of the Cold War was, to my mind, an absolutely classic response that the Chinese would have rooted in their geopolitical and geostrategic thinking. And that remains significant to this day.

When you think about the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the question of the future of Central Asia, the question of the Muslim states there, and the great linkage with Iran and the Middle East across Central Asia, all these are very different from the kind of world that the Anglo-American naval hegemony can deal with.

But their [the US] adventures on the continent have not succeeded. This is quite obvious. They're now even more dependent on their maritime supremacy.

In fact, America, the single superpower that emerged at the end of the Cold War, had hoped to be much more influential on land. They thought that they would reduce the influence of Russia if they could get into the Middle East and get total control there. That was one of the reasons why they took the very dangerous moves they've made into the Middle East, right across North Africa and the Middle East into as far as Afghanistan, and it was not accidental. It was part of a general feeling that if you're the sole superpower in the world, you must not limit yourself to maritime interests. You must also be involved in continental interests.

The US's maritime power and China's BRI

But their adventures on the continent have not succeeded. This is quite obvious. They're now even more dependent on their maritime supremacy. And I think this is what is very much on the mind of the sole superpower, that is, its "remnant power" as it were, is now maritime. The continental side of it, I think they would have to concede that it is not something they can easily control.

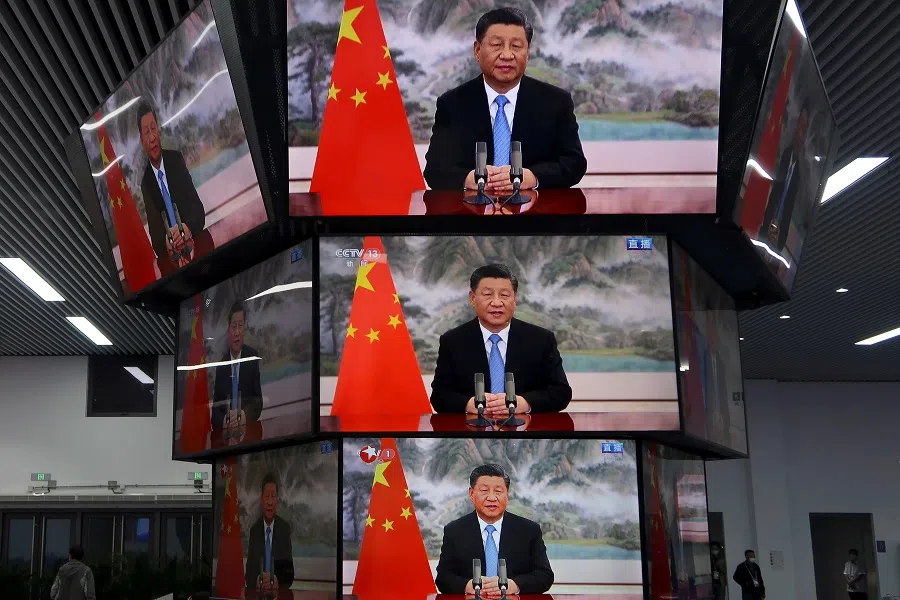

China, on the other hand, has no choice. It has to be both a continental power as well as having an adequate naval defence to look after their existential interests in future economic development. So they are now caught in a very much more complex situation for the first time in history: to be both involved in continental matters as well as maritime matters at the same time. And to find a right balance is what they talked about when they talked about the BRI, the Belt and Road Initiative.

This is a very recent thing in 2013, when Xi Jinping announced it, but actually, this has been going on for at least a decade and a half. Before that, when Chinese investments began to go out, Chinese entrepreneurs - some were private, some were semi-public, some were state-owned enterprises (SOEs) - were actually investing outside, particularly in areas where the Europeans and the Westerners were not interested in, or didn't find it profitable, or found it too difficult, areas where the chances of making profits were very uncertain.

Many of these Chinese took great risks to venture into these areas. And all that had been going on through the first decade of the 21st century without a name. It consisted of different ventures. And the government was aware that some of them were successful, some of them were failures, and had even encouraged some, but in a very unfocused way.

Xi Jinping only became interested in this, I think, when he became vice-president and heir apparent. And by the time he became leader, his advisers and others had helped him think through this to recognise that this all could be pooled together into some state-focused or state-centred enterprise with some strategic meaning behind it. Up to that point, I think up to 2013, all those activities were mainly private initiatives done by very venturesome entrepreneurial Chinese.

Many of the investments are struggling, and they're having great difficulty in keeping them going and making sure that they don't lose. In some places, they may come out better off, but in many cases, they're not at all certain, and this is by no means something that is straightforward. - On the BRI

But from 2013 onwards, they were pooled together, and - what is more - Xi Jinping decided to make it into a big thing to get everybody interested in it. Every province in China had to have a BRI project, and the build-up was enormous. As a result, it actually alarmed everybody. Suddenly, instead of a lot of venturesome, entrepreneurial Chinese trying to make money here and there, it became the Chinese Communist Party behind the BRI. This was now a national project to help to dominate the world through economic debt traps, using debt to tie countries to China. It became very complicated and seen as an alarming strategy for dominating the world.

I think all that is very overstated. There may be a few people who believe that from time to time, and there may be some nationalists in China who feel very proud that they're able to reach out so far. But frankly, if you do the sums, and I believe in Malaysia your experts have done it for Malaysia. Other countries have done it for Indonesia, for Thailand, for Pakistan or other countries, and different parts of Africa. And I think, on the whole, you'll find that the Chinese are not making money out of this.

Many of the investments are struggling, and they're having great difficulty in keeping them going and making sure that they don't lose. In some places, they may come out better off, but in many cases, they're not at all certain, and this is by no means something that is straightforward.

So when you talk about the new Maritime Silk Route, you cannot separate it from the Belt, the continental belt route which is to link up to meet the ambitions of the traders overland. And that is not completely a commercial enterprise.

Land relations strategic and important

The Maritime Silk Route is primarily initiated by commercial interests, with some geostrategic elements drawn into it, after it became an umbrella affair by Xi Jinping. The continental part, the Belt part of it, from the very beginning, way back from the SCO after the end of the Cold War onwards, came from the recognition that they needed to develop their west - the relationships with all those states that were created out of the Soviet Union in Central Asia. Related to this is the fact that China has this very special relationship with Pakistan after the war with India, and that is a very delicate, extremely expensive and very uncertain relationship. But they nevertheless developed it.

They found that it was not enough to have maritime interests because naval power was not in their hands. Naval power can block off, blockade, and contain China to the south, in the South China Sea. And the Chinese can do very little about it. So what they needed was extra access to the Indian Ocean. And this is where, of course, they're actually doing it via land, not by sea.

They're doing it through Burma to Rakhine state, Arakan. And they're doing it through Pakistan to reach the Indian Ocean so they can get at the oil of Iran in the Middle East. And they are also, in other ways, reaching out to the Mediterranean; as I see it, they are trying by land to reach the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. And further north, again entirely by land, all the way to the EU, to Germany, to the North Sea, to the markets of the West.

Many features of this also include our region. In Southeast Asia, the BRI includes land routes through Laos, through Thailand, to Malaysia and Singapore. And then others simply to Myanmar, to Laos and Cambodia, which do not depend on the sea.

The Chinese are realistic enough to know that's not going to be a profitable enterprise. That is a strategic commitment to give themselves access to the Indian Ocean should they ever be blocked by sea. These are long-term views.

So, the Chinese are not forgetting the fact that dependence on the sea is itself not safe. They have to have many ways to reach out to markets and resources. And they have to learn how to deal with the land differently from in the past. But they still have to learn how to do that and cannot put all their eggs in the maritime basket.

So the new Maritime Sea Route has also to be seen as part of that. Maybe even to the extent of saying they may hope to make some money, some profits out of the new Maritime Sea Route to pay for the very expensive land routes which are not going to make them money. I mean, to try and get through the whole of Burma into Arakan, to try and defend the routes to Pakistan from the Hindu Kush to the Indian Ocean, that is not only expensive but also very dangerous terrain.

The Chinese are realistic enough to know that's not going to be a profitable enterprise. That is a strategic commitment to give themselves access to the Indian Ocean should they ever be blocked by sea. These are long-term views.

I do not know whether they'll pay off in the end. But you can see that a change in forces in Afghanistan could make many people do a lot of rethinking about what all this would add up to. And this is not unrelated to the new Maritime Sea Route, for whatever resources they have available to invest in the new Maritime Sea Route has also got to be weighed against all the investments and resources put into making it feasible for the land route to be manageable, to be valuable. And I am far from clear that all this would add up with a plus sign on the ledger.

So if the Chinese can make sure that ASEAN remains autonomous and not take sides, I think they'll be content to see that as a measure of success. To the US, that may not be enough.

Let me conclude, by saying that this new Maritime Sea Route has to face the fact that ASEAN is new, and therefore what happens to us, and how the West looks at ASEAN matters tremendously to them. The rivalry between the US and China means that both sides would like ASEAN to lean to one side or the other. And ASEAN's best bet is to lean to neither, if they can stay that way. And if they can stay that way and stay united, it'll be ideal. But it's far from being a certainty. Both sides will continue to try to at least win some over to each other. So that will be one of the challenges that will persist. And that's something that the Chinese recognise.

And of course, the US has always been interested, because they created the Southeast Asia concept and ASEAN, to begin with. So if the Chinese can make sure that ASEAN remains autonomous and not take sides, I think they'll be content to see that as a measure of success. To the US, that may not be enough. But I think, to China, they would be content if they can keep it that way, they can see that as progress because they had started with as ASEAN established by their rival.

As for the maritime route itself, I would say that they would be very very lucky if they don't lose money there, and if the money they made there could in any way help towards the tremendous cost of maintaining the Belt Road on the continent.

Related: Wang Gungwu: When "home" and "country" are not the same | Wang Gungwu: Even if the West has lost its way, China may not be heir apparent | Connecting Chongqing and Southeast Asia: Challenges and potential of China-Singapore (Chongqing) Connectivity Initiative | Hanging tough together: ASEAN countries' survival strategy amid Sino-US rivalry | How China became Cambodia's important ally and largest donor