Wang Gungwu: When "home" and "country" are not the same

Historian Wang Gungwu speaks to Zaobao about home, country, land, and the world in a globalised era.

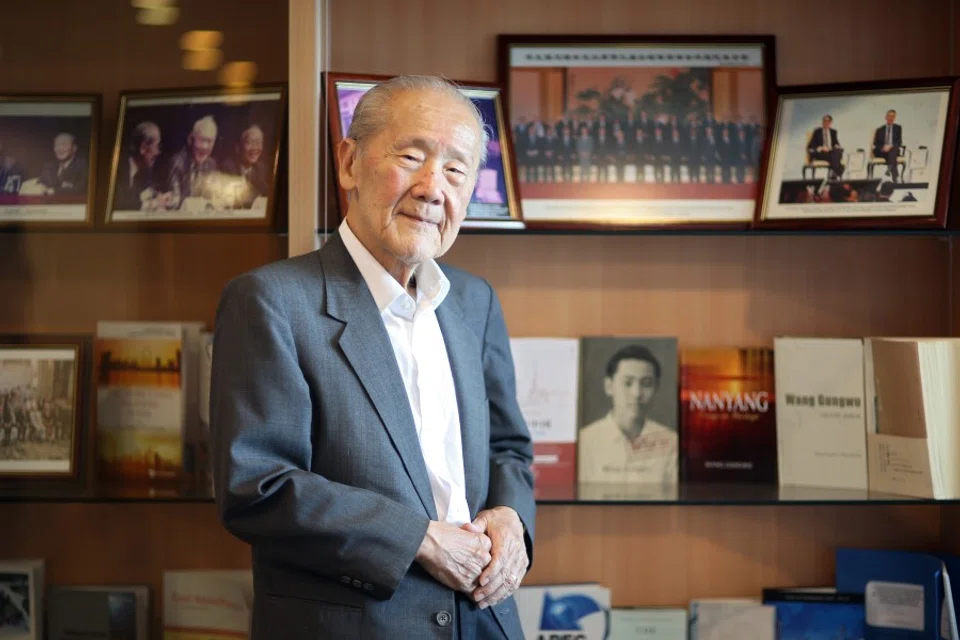

Professor Wang Gungwu stepped down as chair of the East Asian Institute in June 2018. The 88-year-old Australian national has lived in various locations around the world since childhood, including Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur, Canberra, Nanjing, Hong Kong, and London, and has lived in Singapore for nearly 23 years. He and his wife Margaret Lim - the couple married in 1955 in London - estimate that they have moved homes approximately 20 times.

Speaking to Zaobao last year on the publication of his two English books, Nanyang: Essays on Heritage and his memoir Home Is Not Here, the sprightly Prof Wang muses, "The older I get, the more clearly I remember the past. I'm getting long-winded!"

Nanyang is a collection of eight speeches, covering topics including Singapore's nation-building, national ideology, group identity, and the passing down of cultural heritage, while Home is his first memoir, highlighting his life in Ipoh and Nanjing until the age of 19. Home also includes snippets of the memoirs his mother, Ding Yan, addressed to her son. She wrote them in her seventies, and Prof Wang in turn translated parts of it for his own children, which appear in Home.

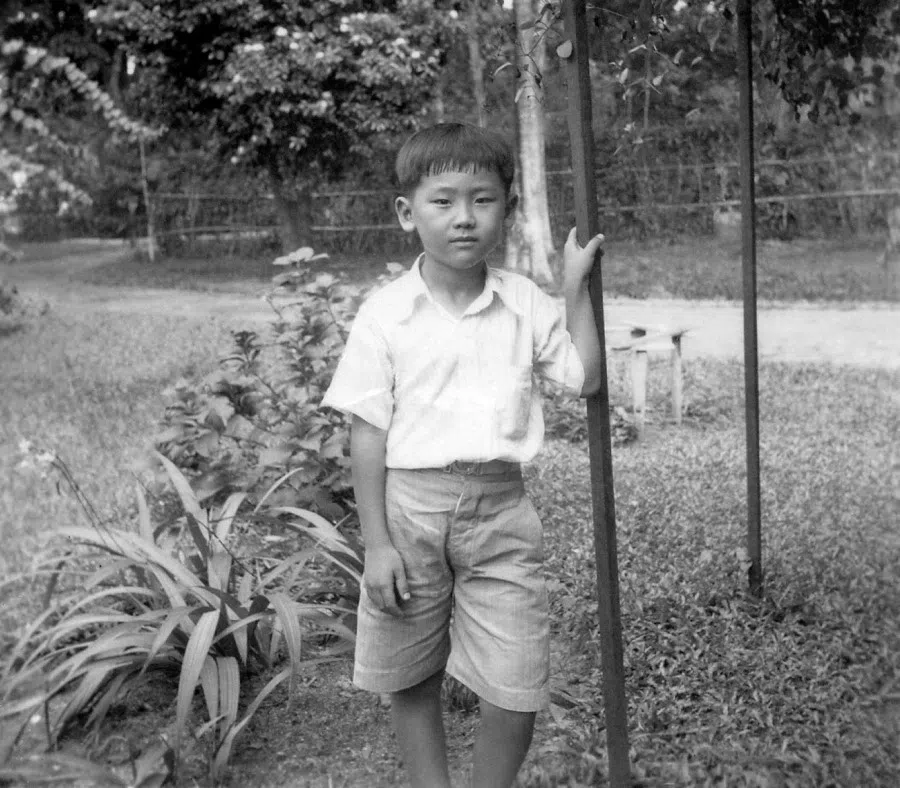

Prof Wang grew up in Ipoh in colonial Malaya and went through the Japanese occupation during World War II. Before New China was established in 1949, he studied for a year at Nanjing University (then National Central University) before the Chinese Civil War prompted his parents to summon him back to Malaya, where he attended the University of Malaya.

Prof Wang grew up thinking about "going home". His ancestors were originally from Taizhou in China, while he himself was born in Surabaya, Indonesia. As a result, despite growing up in Ipoh, Malaysia, he did not consider it his home. His parents always taught him that "home" was China, while Malaysia was just a temporary abode. All they wanted was to go home.

Seventy years later, reflecting on what "home" meant to him, Prof Wang says his concept of "home" has changed. He long ago stopped seeking one "home", but is content to have the notions of nationality, culture, and space take on multiple meanings.

When he was a child, his mother's home was the one found in China, the ancestral home of the Wang and Ding clans of his parents' generation, the home in Taizhou where his grandparents, relatives, and friends were. But as a youth, Prof Wang was no longer clear about the relationship between home and China. He explains, "At the time, my home was in China, but 'in China' is different than 'China'."

His confusion about "home" mingled in a complex swirl with his feelings about his family, hometown, and the building of a new nation.

Prof Wang returned to Malaya at 19, to a post-World War II Asia high on nation-building. Many places, including China, were talking about nation-building and putting the nation above all else. The problem was that, in the first place, they were not even clear what a nation was.

As a historian who has lived in many cities around the world, Prof Wang now holds that "home" and "country" are not the same.

"National identity is just one point where 'home' begins, but 'home' may not refer to a country. Especially in a globalised world, 'home' and 'country' are not the same. These two concepts have become very broad and are not confined to any region, government, political party, or ideology. Those are just elements of 'nation' and 'home'. So the concept of home becomes a personal question, a question of how one thinks."

On culture and cultural identity

Even as a child, Prof Wang identified with Chinese culture. He believes that cultural identity is linked to home and country, but culture does not stay the same forever. "Culture is not something held rigidly in a container. It is always changing because of cross-cultural contact. The Chinese culture I identify with may be different from what you identify with, but that's fine. They have things in common, and we can understand each other."

The point seems to be that "home" and "identity" are not clear-cut, and they do not need to be.

Prof Wang continues, "Even as I identify with a culture, I can also identify with a country, the home and abode of a family member, my ancestral home, and all of that. There is no contradiction. This is what my own life has taught me. In other words, I can be loyal to one country while simultaneously identifying with a different culture or set of values.

"The culture and values I identify with may not be the country's values. Some countries do not allow any differences, but that's not necessarily correct.

"Do I give up the culture I identify with just because the country doesn't identify with it? I don't think that's right. But most countries are not like that. Most countries feel that individuals have the right to think for themselves and the freedom to identify with whatever they want."

On "Nanyang" and passing down culture

Prof Wang has spent nearly 50 years in the Nanyang region (generally referring to the area south of China, i.e., Southeast Asia). He says the term is an emotive one.

"In the late years of the Qing dynasty, the Manchus built a navy and started distinguishing between the seas to the north and south of China. And so, the idea of Nanyang (南洋, South Sea) was born.

"Japan also called the area south of Taiwan Nan'yō, covering Australia and the Pacific islands such as Papua New Guinea and Hawaii. This was also linked to the establishment of the Japanese navy.

"In Southeast Asia, Nanyang generally refers to Singapore and Malaysia, Java, Sumatra, and Borneo in Indonesia, and the coastal areas of Thailand.

"In the late 19th century, the Qing dynasty set up its first regional consulate in Singapore. They needed a name for the area, and 'Nanyang' stuck.

"So the idea of 'Nanyang' has been around for at least a century, and the name was commonly used in the 1950s and 1960s. When I was a child, 'Nanyang' and 'overseas Chinese' were practically synonymous. We generally spoke of 'overseas Chinese in Nanyang' (南洋华侨). The term originally did not carry any political significance, until Sun Yat-sen called them the 'mother of the revolution'. That's when political awareness of the term's significance began. The term was retained when the People's Republic of China was established. At that time, the Kuomintang's regional branch was called the Nanyang branch, just as the Communist Party of China's equivalent branch was.

"As I understand, the Chinese in Vietnam and Myanmar do not use the term 'Nanyang', and it is seldom used in Thailand. It is mostly used in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, which is appropriate, since they are islands and maritime countries.

"Myanmar and French Indochina are different. They are mainland bodies, not located in the ocean. So 'Nanyang' meant going from the South China Sea to other island states, and the Malay Peninsula is the heart of Nanyang."

As it happens, Singapore has a prime location in the heart of Nanyang. It is no wonder then that the people in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia naturally feel something for the region. "'Going south' to Nanyang meant going from China to Singapore, then switching boats bound for other destinations. After Sun Yat-sen came to Nanyang in 1900, Singapore became the centre of Nanyang because its transportation was convenient and its port good."

In recent years, the term "Nanyang" has sparked debate in Chinese cultural circles in Singapore and Malaysia. Some feel that Malayan or Nanyang culture, along with one's ethnic culture, can simultaneously constitute Singaporeans' cultural foundation. Others feel that Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia are now independent nations, while the term "Nanyang" has long been associated with China and the identity of overseas Chinese, and so Singapore should stop using the term in discussions about culture, focusing instead on Singapore. Another mindset, most commonly espoused by members of the Malaysian Chinese community who advocate applying for heritage status for Nanyang culture, is that "Nanyang" is in fact Malaysia's intangible cultural heritage.

Prof Wang feels that when it comes to passing down culture and heritage, it is important to let go of political baggage and focus on cultural values. "It is understandable that we tend to talk about Nanyang in terms of cultural identity and sentiment, because it is a legacy. Today's idea of Nanyang is different from the original concept. The idea is always evolving, and it has become a local perspective."

In his view, the local perspective of Nanyang first began in the 1920s-1930s, reaching its peak in the following two decades. "The Chinese who identified with this region had things in common. They knew one another's trading culture, and they came into contact with Malay culture, which gave them a fresh understanding and perspective of the region. This localised version of Nanyang should not be confused with the original concept from China."

The concept of "Nanyang" has a long history and has gradually evolved into a cultural heritage. Prof Wang says, "How you use that heritage is up to you. If you don't use it, that's fine too. It doesn't matter." He adds that each group has the right to choose how they see cultural heritage. "Heritage is one thing, while passing it down is another. There is a choice in passing it down. It is something that is done because you feel it's worth it, that it has value, that the next generation needs to understand it. If you feel the idea of Nanyang is worth passing down, that's your decision."

In an increasingly globalised world, each culture has a choice regarding what to pass down, including large countries. Prof Wang says, "China also has a decision to make regarding what kind of cultural heritage and values to pass down to the next generation. China is currently facing unimaginable societal changes. In fact, China once wanted to destroy Confucianism, but it would not die. It kept going. It has its values and essence, there are great things about it. What matters is to let go of what is not worth keeping and pass down what is worth keeping."

On the Nanyang network and ASEAN's success

Before national borders were drawn up and formalised, it was natural for the Chinese in Nanyang to move freely between countries and borders. Prof Wang says this early network was one of the reasons for the success of ASEAN.

"Previously, when we spoke of Chinese people moving between nations, it was really referring to moving across borders. At the time, there were no national borders as we know them. During the colonial period, with the exception of Thailand, all of Southeast Asia was controlled by foreigners, so it was natural for people to move between countries. Especially in economics and trade, people went wherever the business was. Many Chinese had relatives in Penang, Sumatra, Singapore, and even the south of Thailand."

After the ASEAN countries were formed, even though there were issues of international relations, customs, and import/export procedures, the trade networks of the Chinese in Nanyang did not change much. Prof Wang says that Southeast Asian countries saw the advantages of these networks and tried to simplify processes as much as possible.

"Southeast Asia was also part of why ASEAN succeeded. Nanyang was organic, and it succeeded. It has deep roots."

On the Nantah merger

An interview on Nanyang would not be complete without a mention of the 1980 merger of Singapore University and Nanyang University (Nantah).

In 1964, the Singapore government appointed Prof Wang, who was then teaching at the University of Malaya, to head a committee to review courses at Nantah. The report was submitted in May 1965, and released in September of that year, following Singapore's separation from Malaysia. Prof Wang was thus drawn into the incident that sparked a discussion that has yet to subside even today.

In Nanyang, Prof Wang says Nantah's establishment put "Nanyang" back into a central position for Chinese Singaporeans, while "cross-border" Chinese saw Nantah itself as the focus. He adds that the Nantah merger created a cultural vacuum in Singapore.

Prof Wang says, "I was sorry to see the Nantah merger. I felt it was unnecessary. I was totally against it. But it was a problem for the country."

"Nantah was also a form of cultural heritage, it could have been allowed to go on. With today's environment, it wouldn't be hard for it to succeed. From an educational perspective, I feel there was no need for the merger."

He says the nation had its own needs, but in the view of this lifelong tertiary-level educator, the merger could have been avoided. "A university that was built over such a long time has its traditions, its basic system, method, culture, and character. It should have been allowed to grow independently into an excellent university. As an educator, I think it would have been ideal to let it fulfil its potential.

"It was not in a vacuum. There was something there. Take that away, and of course there's just a vacuum left, which cannot be preserved."

Prof Wang says the merger was the state's decision. "Nantah was also a form of cultural heritage, it could have been allowed to go on. With today's environment, it wouldn't be hard for it to succeed. From an educational perspective, I feel there was no need for the merger."

On Singapore culture

Since the 1980s and 1990s, there have been discussions about "Singapore culture". In his book Nanyang: Essays on Heritage, Prof Wang mentions that in a globalised world, it is not feasible to have just one unique, unifying culture. "Culture and nation are different. In nation-building, a boundary is drawn, and within that boundary is the nation. We want standardisation inside that boundary, but if we want everything to be the same, we have a big problem. If we want diversity, we cannot seek standardisation.

"The world today is different than before. We are not isolated in some corner of the world. Singapore is at the centre of globalisation. It is a very important port, a globalised city. So what is this talk of a single culture? It is not even easy to speak of it as a nation on its own. Diversity has to become a matter of course.

"All modernisation is globalisation, which is inseparable from the nation, and for this reason, we have seen great changes in the very nature of culture."

On globalisation

The globalised world is one giant ecosystem. Prof Wang says Singapore, being a part of this ecosystem, also has deep-running internal struggles.

"How does a globalised city and a city-state come together? It is a nation, and a globalised city. It's all relative. For both to exist at the same time, there will be many problems. This in itself is a big problem."

In Singapore's early days, nobody predicted the enormous power of globalisation. Prof Wang suggests that Singapore succeeded because it was on board with globalisation, which affected its nation-building process.

"Because it accepted the challenges of globalisation, Singapore has changed greatly. It's very different from how people would have envisioned it to be during the early period of nation-building. Leaders' needs and the problems they face are separate issues. Cultural integration, the concept of nation, and everything of that nature was affected. There's no secret recipe for handling it, except to keep responding and adapting. There's no easy answer."

Prof Wang points to the ways in which a big country like the US also feels the threat of globalisation. Similarly, he feels that for China, its 5,000 years of history is a double-edged sword. Amid the changes wrought by globalisation, history is an anchor of stability, but also a form of baggage. Singapore has no baggage, so it can decide immediately what to do. But if there is baggage, historical issues prevent certain things from being done.

"Cultural heritage is the basis of stability, but if you don't know how to use it, it shackles you so firmly you can't walk."

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao on 9 September 2018.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)