Wang Gungwu: The high road to pluralist sinology

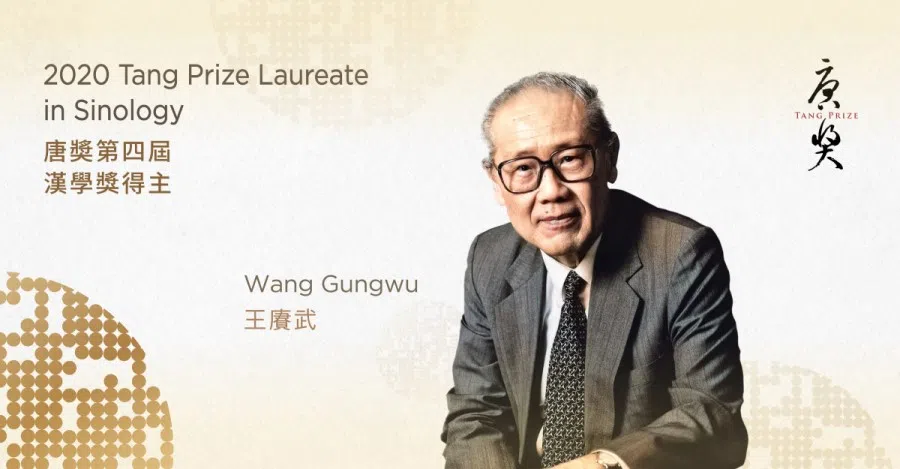

Professor Wang Gungwu, eminent historian and university professor of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the National University of Singapore, was awarded the 2020 Tang Prize in Sinology earlier this year. At the 2020 Tang Prize Masters' Forums - Sinology held last month, Professor Wang traced the evolution of sinology in the West and East, observing that today, a "pluralist sinology" is emerging alongside a rising China. This allows for the term "sinologist" to be applied to a much larger group of scholars, and for the bringing together of various knowledge traditions and academic disciplines in the study of China. While there is much to be cheered by this, Professor Wang also urged his fellow scholars to be ready to "douse the fires that others had fanned", as knowledge gathered by pluralist sinology could be used as a weapon amid intense rivalry between the US and China. This is the transcript of his speech.

I am very honoured to have been awarded the Tang Prize in Sinology.* This led me to rethink what my understanding of sinology has been and why I find it difficult to decide who is and who is not a sinologist.

Sinology in the West began as an extension of European classical studies of what they saw as the Orient, hence it had its beginnings as orientalist sinology. In Chinese, it came to be known as hanxue (汉学), but was not the same as the scholarship in Qing China that went by that name. By the early 20th century, however, Chinese scholars working with Western sinologists accepted that the work they did together was a modern form of hanxue. In time, as more social scientists worked on China and new generations of Chinese mastered the social sciences, sinology was brought to a larger frame of China studies.

Today, a new stage is emerging because a rising China is calling on its civilisational heritage to be fused with modern notions of progress to make it a new force in world affairs. This is a big step towards a pluralist sinology that allows us to use the term "sinologist" to apply to a much larger group of scholars.

The idea of pluralism derives from at least four sources. First, hanxue sinology covers the total body of work by scholars with different cultural and national identities. Second, the foundations have been built on classical Chinese and several other knowledge traditions. Third, the multiple premises used in scholarship are drawn from more than one academic discipline. Fourth, the plurality makes the new sinology useful for China's future development but may also serve a variety of political agendas.

By going on this high road, the scholars who embrace a more complex view of sinology are open and inclusive. They are ready to learn new ideas and methodologies in order to extend our knowledge of China and improve our understanding of how a people from an ancient civilisation had come to embrace revolutionary change and to pursue progress wherever they think they should.

Sinologists became past-oriented and curious how quickly Chinese culture had become decadent.

Orientalist sinology

I shall begin with the first sinologists I encountered. In 1954, when I went to study in London, the top sinologists were all Europeans, with a few Japanese scholars whom some of the Europeans had admitted into their company. I was a history student from a colonial university in Singapore modelled on those in Britain. There I had read work by sinologists and was impressed by their ability to extract materials from Chinese records to reconstruct the history of the lands between India and China. That sinology was an extension of the Oriental studies that developed out of Classical studies and had served the needs of the European imperial powers.

"Orientalist sinology" was based on the study of languages and philological methods; it was holistic in approach towards understanding a once admirable civilisation. Sinologists were also knowledgeable about some of the cultures and peoples across the Eurasian continent between Europe and China. Their work covered a variety of texts and material remains that stretched back for millennia. Very few scholars entered this field, but the best of them were successful in mastering many of the languages involved.

On China itself, Japanese scholars had made their own contributions with their shina gaku (支那学, zhinaxue). Some also joined the Europeans to study North and Central Asia. Chinese scholars, on the other hand, were slow to take the work of outsiders seriously. However, by the 1930s, through the translations of European and Japanese writings by Feng Chengjun (冯承钧) and Zhang Xinglang (张星琅), more Chinese had come to respect the work of some of these sinologists.

For most Chinese who accepted the cyclical view of history, Qing China's decline was not surprising. Few noted that their civilisation was threatened with collapse. Therefore, most Chinese scholars thought that orientalist sinology was fundamentally flawed.

The major obstacle to collaboration and mutual respect between Chinese scholars and these sinologists came from the underlying assumptions in orientalist sinology. Unlike for the earlier Jesuits, by the 19th century, the time for wonder at Chinese achievements was over. What replaced the earlier admiration was the focus on the death throes of a remarkable civilisation. Sinologists became past-oriented and curious how quickly Chinese culture had become decadent. A few did find Chinese efforts to learn from the West interesting while others admired the legacy of literature and the arts. Yet others were sad that the ancient virtues had failed altogether. They thought that the modern revolutions that convulsed China only brought tragedy for the Chinese people.

For most Chinese who accepted the cyclical view of history, Qing China's decline was not surprising. Few noted that their civilisation was threatened with collapse. Therefore, most Chinese scholars thought that orientalist sinology was fundamentally flawed. In contrast, their own China studies or guoxue (国学) was vitally concerned with finding lessons from the past to help them deal with new challenges. Their positive approach managed to survive two revolutions and remains important to the present day.

The rise of a new China was what made the difference. The orientalists were forced to divide between those who concentrated on the textual and philological base of sinology and those who agreed that China studies should welcome the participation of social scientists.

Modern Chinese studies

Let me now trace the fall of orientalist sinology. It had its glorious moment when it was part of the first Congress of Orientalists in Paris in 1874 and dominated Western studies of China for over 70 years. After World War II, a new generation met separately as "young sinologists" every year. An intriguing moment came at the meeting in Paris in 1956, when four senior scholars from the People's Republic of China (PRC) came to participate. That was when a post-colonial consciousness had discredited the study of "Orientals". Not long after, these European sinologists adopted a new name, the European Association for Chinese Studies, and included the study of modern China.

The rise of a new China was what made the difference. The orientalists were forced to divide between those who concentrated on the textual and philological base of sinology and those who agreed that China studies should welcome the participation of social scientists. This began in the US in the late 1950s where the PRC was now part of the enemy in the Cold War struggle for dominance. New funding was made available to encourage a new generation of scholars to study this phenomenon. Also, some scholars, notably anthropologists and modern historians, saw that the Maoists were not mere followers of the Soviet heresy of the West. China was also using its ancient past to redefine its role in the world. And economists and political scientists began to see that the PRC was not a vassal of the Soviet Union.

The sinologists were thus forced to acknowledge that the field had slipped onto a low road. If they did not take into account what this China was reconstructing, that would lead them to irrelevance. To avoid that, they needed to recognise that there were alternating breaks and continuities in China's journey from ancient to modern. Some began to see that they could use other methodologies to help them extend their scholarly range.

Thus a new cooperative effort that combined hanxue and the emerging modern China studies was needed. This was a difficult and confusing period. We need a full chronology of the scholarship that began to combine what was evolving inside and outside China between the 1960s and the 1990s.

Those sinologists' main contribution was to bring China into the comparative studies of civilisations.

I believe there are lessons here in the ups and downs of sinology. When it was a branch of Oriental studies, it boosted European belief that their modern achievements had established universal standards for civilisation. The world would need to conform to those standards if they want to progress. While there is truth in what the Europeans claimed for the scientific revolution and industrial capitalism, their ideological claims had not been acceptable, not in the Islamic realms, nor in Hindu and Buddhist polities. Even for East Asian countries that wanted progress and development, changes were partial and came about with reluctance. China's painful experiences over the past 150 years have shown why studying China requires us to understand why its people today still expect to preserve key parts of their rich heritage. Orientalist sinology that saw China's past as no longer useful failed to provide students today with that understanding.

However, the hanxue outside China was largely based on the huge body of knowledge that Chinese scholars themselves had accumulated for at least two millennia. Those sinologists' main contribution was to bring China into the comparative studies of civilisations. The scholars showed in what ways China was different from the Mediterranean civilisations and how Chinese values could be compared to those of India and the nomadic worlds of central and northern Asia. By linking the scholarship of ancient civilisations systematically, the sinologists highlighted the distinctive qualities of Chinese civilisation.

Once the peoples of such decadent empires were made colonial subjects, the Europeans gathered their artefacts and documents for their museums and libraries.

That scholarship had originated from genuine respect for the cultural and organisational achievements of ancient China. Its influence on Europe has been richly captured in the reports by the Jesuits and, more recently, in the volumes published by Donald Lach, Asia in the making of Europe. But the 18th century European Enlightenment and its idea of progress soon reduced that kind of writing to a minor branch of knowledge.

In particular, after the Macartney mission to the Manchu emperor Qianlong in 1793, admiration had turned into exasperation followed by distrust and condescension, as recounted in Lo Hui-min (骆惠敏)'s 1976 Morrison Lecture, "The Tradition and Prototypes of the China-Watcher". Once the imperial powers realised that Qing China was no longer strong and its people were poor and discontented, their attitudes changed. The Qing rulers were then seen as mere oriental potentates ready to be displaced. Once the peoples of such decadent empires were made colonial subjects, the Europeans gathered their artefacts and documents for their museums and libraries. China's past glories would meet the same fate and were also stored together with those of defunct ancient civilisations like Egypt, Babylon, Persia and Greater India.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to dismiss the scholarship of the best sinologists who were open-minded and dispassionate.

By the end of the 19th century, Western powers expected Chinese ideas and institutions to be replaced altogether by their triumphant universal values. Scholars adopted scientific methods to study state and society and sinology no longer had any influence on new developments. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to dismiss the scholarship of the best sinologists who were open-minded and dispassionate. Some of their work did correct the biases among those foreign leaders who preferred China to be weak and ripe to be carved up.

Chinese scholars respond

Among China's own scholars, there were several false starts in their response to the new challenges. The first was when Chinese students returned from the West. They were critical of past traditions of learning and sought new ways to achieve the progress they wanted for the country. The excitement generated among the young after the May Fourth Movement led to some innovative thinking. A striking example was to decide that China's modern history began with the First Opium War in the 1840s. That way, everything earlier was declared "ancient", "feudal", even "obsolescent", studied only for the lessons they could teach about what made China's fall inevitable.

...there was almost no scholarly work published in the PRC from 1957 to 1978 that is worth anything.

The second came when a combined civil war and Japanese invasion destroyed the Nationalist regime. The efforts to develop a modern guoxue to compete with sinology-hanxue came to nothing. Guoxue was replaced by an ideology-driven rewriting of the past to fit a Marxist-Leninist framework. At this point, even the established sinologists of the Soviet bloc were suspect, and were lucky to be politely received in China.

Thereafter, for over thirty years during the 1950s-1970s, domestic disputes within and the total rejection of the China studies of the West brought the study of China to a state of confusion. On the one hand, there was increased collaboration between orientalists and modernists, notably in the US. And Chinese academics working in the West began to work with their Western counterparts. And those scholars exiled to Hong Kong and Taiwan were actively refreshing their guoxue heritage in cooperation with these modern sinologists. On the other hand, there was almost no scholarly work published in the PRC from 1957 to 1978 that is worth anything.

Deng Xiaoping's reforms made another start possible. The resumption of academic exchanges enabled PRC scholars to explore the new hanxue or China studies and focus on the contributions of the social scientists. Others who resumed their work within China resuscitated the guoxue that had been set aside. There was also some recognition that, among the millions of Chinese who had settled abroad, different perspectives about their ancestral homeland had emerged. These Chinese overseas lived and worked among other peoples and cultures and saw different dimensions of what China was, and what being Chinese might mean. Perhaps their self-awareness required a different kind of hanxue or China studies that would make the field more pluralist.

Pluralist sinology

I am unable to pinpoint a moment in the 1980s when a pluralist sinology might have begun. What is clear is that a rising China encouraged a widening of interests, not least by giving more choices to scholars in the PRC. I recall being struck at the conferences organised in the 1980s by scholars in Taiwan and Hong Kong who were willing to call their work hanxue. They debated with their counterparts working in Western universities about developing a Chinese hanxue with the support of those working in the PRC. And some from the PRC seemed keen to join them in that venture.

Of particular interest to me was the conference in 1991 organised by the Department of Chinese Studies at the National University of Singapore (汉学研究 之回顾与前瞻). Here were Chinese scholars in a multicultural nation inviting Chinese scholars from the PRC, Hong Kong and Taiwan universities to share their experiences with a new kind of hanxue. The location was neither Western nor Chinese. The papers presented were marked by different understandings of what Hanxue could mean, for example, whether hanxue was an inseparable part of China studies, whether it was distinct from China's own guoxue and should be identified as guoji hanxue (国际汉学), or whether it could be a distinctive field of study that cooperated closely with the new sinology in the West.

I see three levels of cooperative effort that can draw on the best work done by generations of sinologists: those of early hanxue or orientalist sinology, a century of guoxue scholarship, and the new sinology that includes the work of social scientists.

It is possible to group the major ways that China is being studied today. It is about an ancient civilisation that rose again after a spectacular fall. It is about examining how a rising power is challenging Western dominance. It is also the study of an exceptional kind of nation-state that is ambitious to regain the respect it once enjoyed and do that without making its smaller neighbours fearful of its wealth and power. It is all of the above, and one could add more. Having to face such differences, getting onto the high road of pluralist sinology may be a good step forward.

What does this pluralism mean here? I see three levels of cooperative effort that can draw on the best work done by generations of sinologists: those of early hanxue or orientalist sinology, a century of guoxue scholarship, and the new sinology that includes the work of social scientists.

We know that orientalist sinologists contributed to our knowledge of how China interacted with its multifarious neighbours, in particular the continental forces that attacked and ruled China as conquerors. Those scholars had shown how non-Chinese sources from other parts of Asia could illuminate many areas of Chinese history. Later, the best guoxue scholars in China accepted the value of their investigations and, in particular, greatly appreciated the archaeological skills that these sinologists had introduced.

Traditional guoxue scholars like Kang Youwei were confident and open-minded about what they could do to enable China to become modern. Others like Zhang Binglin were convinced that Chinese values were as good as, if not more mature, than Western traditions. Yet others were prepared to acknowledge that Japanese shina gaku did inspire fresh thinking and also thought that some of the Chinese scholars who studied abroad deserved to be heard.

In that context, guoxue in China emerged as distinct from the hanxue that Western scholars produced. To Chinese scholars, that hanxue might have satisfied antiquarian curiosity but their guoxue was purposeful and rooted in the jingshi (经世) tradition in which scholars worked to make China admirable and secure. Here the real challenge came from the social scientists. They represented the Euro-American equivalent of the jingshi tradition and were developed to measure current problems of material progress. By using constantly improving scientific methods, their work could also demonstrate Western achievements to the rest of the world.

For both powers, the knowledge gathered by pluralist sinology could serve as a weapon, for either self-defence or for intelligent offence, under conditions of intense rivalry.

The Chinese universities established at the end of the 19th century and modelled on those of the West and Japan began by insisting that mastery of classical Chinese was essential for any serious study of China. But younger scholars believed that modern science and academic disciplines were necessary for the country's future progress. New subjects like economics, law and administration, sociology, geography, and psychology became more attractive, and their analytical methods led scholars to conclude that their older holistic tradition was unscientific. Thus the 文史哲 (wenshizhe, literature, history and philosophy) pillars of guoxue were separated.

This did not prevent scholars from being as holistic in approach as they wished but made it easier for new kinds of cooperation to emerge. That way, it extended the depth and breadth of Chinese scholarship. What makes it pluralist comes from the many autonomous ways that scholars today can draw on different clusters of skills and insights. Taken together, this enables them to explain and understand why and how a modern state connects with its ancient foundations. The methods of classical hanxue are found to be compatible with those of modern Guoxue in China. Classical scholars within and outside China are now familiar with the new methodologies used in the social sciences.

However, there is one added dimension to the plurality that is not welcome but cannot be avoided. A strong and ambitious China is now seen by the global superpower, the US, as a threat to its supremacy. For both powers, the knowledge gathered by pluralist sinology could serve as a weapon, for either self-defence or for intelligent offence, under conditions of intense rivalry. In that way, as the large and varied internationalist sinologists try to work together, they can see that this high road can also be a dangerous one. They will have to learn how to wield their knowledge not only to defend the integrity of their profession but also to help douse the fires that others had fanned with their inbuilt or policy-determined biases. On this high road, that sensitive and difficult task will always be a severe challenge. But it remains a unshirkable responsibility to confront that challenge.

*The biennial Tang prize, established by Taiwanese entrepreneur Dr Samuel Yin, recognises achievements in the fields of sinology, sustainable development, biopharmaceutical science and the rule of law. The Tang Prize in Sinology "recognises the study of sinology in the broadest sense", paying tribute to those who have advanced research on China and its related fields such as Chinese thought, history and literature.