Chiang Hsun: The freed poet in rainy spring, by the Yangtze

Chiang Hsun writes about the third-best semi-cursive script by Song dynasty poet Su Shi in this third part of his series of articles on Chinese calligraphy. He reconstructs the circumstances of the calligrapher, who had just been released from prison and was sent to Huangzhou along the Yangtze river in a rainy spring. He muses that calligraphy is as truthful an artform as it gets. Its aesthetic qualities dictate that outpouring of emotions are captured in every brushstroke; the artist's state of mind and the milieu of the times he depicts are laid bare for all to see.

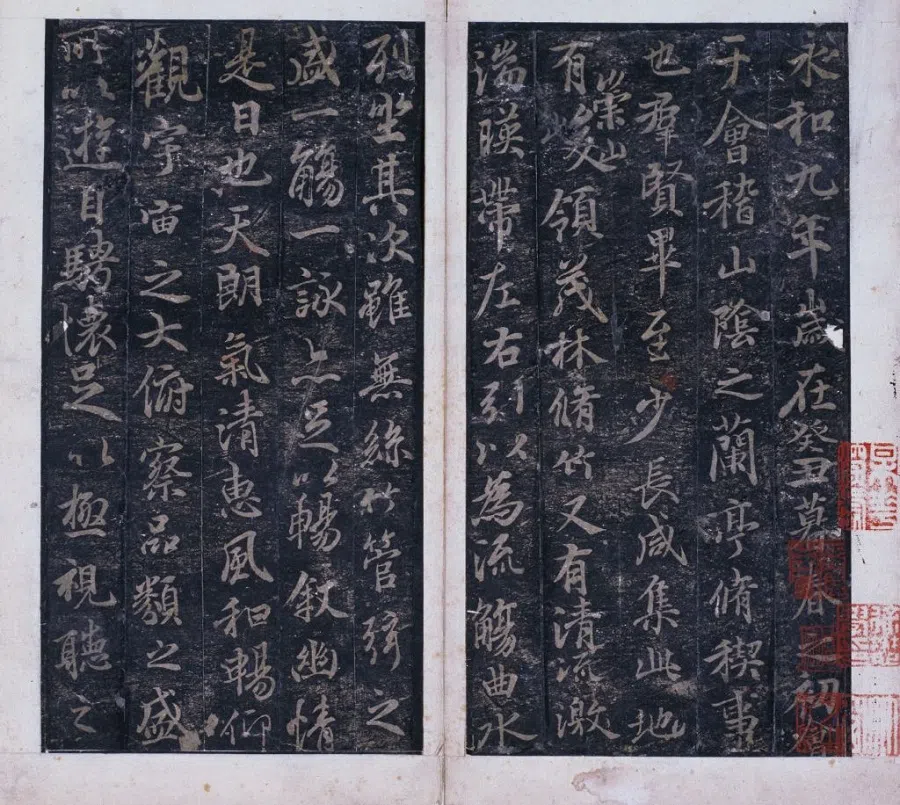

I've admired Wang Xizhi's Lanting Xu (《兰亭序》, Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection) - what is considered the most outstanding semi-cursive script (行书) in Chinese calligraphy - while visiting the Orchid Pavilion in the suburbs of Shaoxing a few times around 3 March of the lunar calendar. I went there to imagine the days of the ninth year of Yonghe thousands of years ago. War had just subsided and people were recovering from the trauma of it all. Surviving refugees had spent numerous springs in the south, but finally, spring was beautiful to them again. As it says in Lanting Xu: "The sun is beaming and the air is fresh. How soothing is the warmth of the spring breeze."

Yet, families and the country were completely torn apart, and chaos and tragedy reigned - misery was everywhere, grief pierced the heart and it was dripping blood. To get the essence of the line in Lanting Xu that reads "looking up to see the grandeur of the universe", one actually has to also read Sang Luan Tie (《丧乱帖》, The Ravage of Ancestral Graveyard) and Pin You Ai Huo Tie (《频有哀祸帖》, The Recurrent Tragedies), which are now preserved in Japanese collections. It is then that one can hear and discern the cries of history beneath Wang's unrestrained and elegant penmanship.

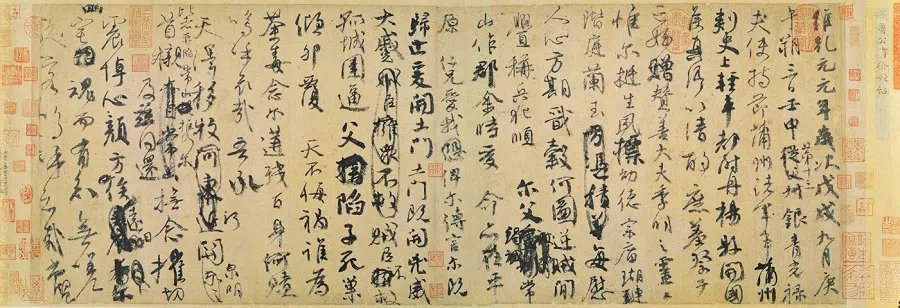

Yan Zhenqing's Ji Zhi Wen Gao (《祭侄文稿》, Eulogy for a Nephew), thought second only to Lanting Xu, is a painful eulogy written after Yan found his nephew Yan Jiming's decapitated head amid a corpse-filled battlefield. Without such a historical tragedy, it is hard to understand just how much blood and tears were behind the manuscript's multiple corrections.

The world's best and second-best semi-cursive scripts are both historical documents. If one nitpicked and fussed over calligraphy standards, tried to perfect reproductions of Lanting Xu, and replicate Zhao Mengfu's masterpieces like the originals, without including any individuality or signs of an era - then one would really be far away from true calligraphy.

Indeed - true calligraphy fails to exist without individuality and signs of an era!

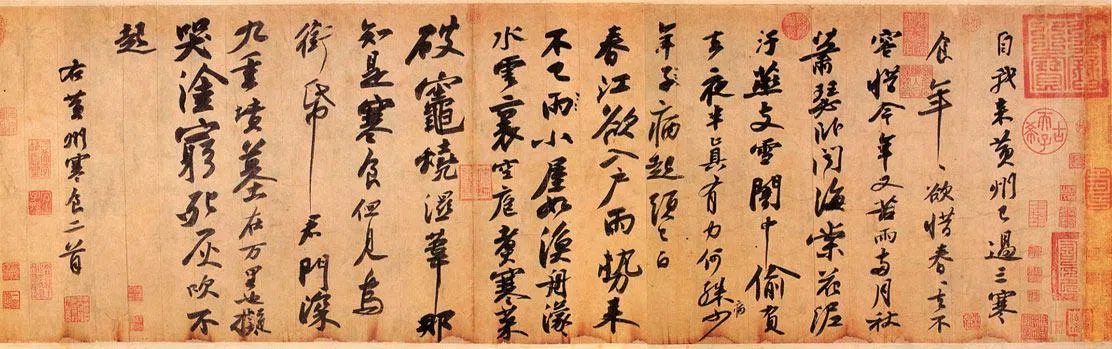

Calligraphy pieces bear witness to the times - Lanting Xu was a testament to the Jin dynasty, as was Ji Zhi Wen Gao to the Tang dynasty, while Su Shi's Han Shi Tie (《寒食帖》), the world's third-best semi-cursive script, shed light on the Song dynasty and the poet's magnanimous and upright character despite being a victim of miscarriages of justice.

When I was in my 20s, I studied Han Shi Tie with my teacher, Zhuang Yan, at the National Palace Museum. A line reads: "Three Hanshi Festivals (lit. Cold Food Festivals, local celebrations to commemorate the death of the Jin nobleman Jie Zitui) have passed since I came to Huangzhou." Su Shi had just been released from prison and ended up at Huangzhou. It was around the Qingming Festival in spring; possibly it was the Hanshi Festival then - rain was falling ceaselessly and the rivers were vast and mighty.

Another line reads: "My humble abode is like a small fishing boat, floating about amid the blur of the rain." This is a manuscript and he wrote whatever came to mind. Mistakes, strikethroughs, characters written big and small - it was all very disorganised and erratic. Being an original manuscript, the work showed how Su Shi's spontaneous emotions flowed right into his words like music with rhythm and cadence - that's why Han Shi Tie is such a study in aesthetics.

Calligraphy is not something to be understood through tittle-tattle or arguments; it needs an open and deep heart.

If you could copy it and write it neatly again, it wouldn't be the third-best semi-cursive script. The semi-cursive script is an expression of one's spontaneous feelings right at a particular moment. It is more authentic than Chinese characters themselves. Anger, sadness, love and hate - everything can be read from it. This is what calligraphy is.

Still unable to understand calligraphy after looking at the world's top three masterpieces? So be it then. There's no need to waste time explaining. Calligraphy is not something to be understood through tittle-tattle or arguments; it needs an open and deep heart.

In life, there may be tragedies and partings; in life there may be the cries of an era. Yet again in life there may be insults and ridicule, injustice and oppression. One might experience incomprehensible anxiety and panic. When that happens, pick up a calligraphy brush and watch how the lines of ink spread across the paper. You'll then understand what's a dian (、), what's a na (㇏) , and what are the rhythmic transitions and pauses (duncuo, 顿挫) in a piece of work. But there would be more tear stains than ink stains, for the aesthetics of calligraphy reveal not Chinese characters themselves, but the blood and tears seeping through each historical document.

I shed tears still

In memory of

Beauty and yesteryears

I shed tears still

Drop by drop, each one

Shall return to the rivers and its land

I only wish to write about what's in my heart. And without a doubt, what can be remembered and forgotten, are not only these.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)