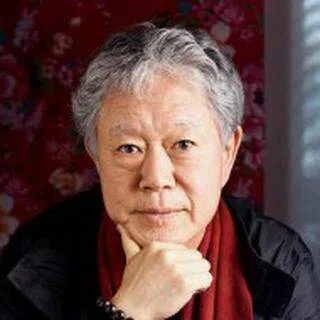

Chiang Hsun: How great a mark of rebellion it is to hold an ink brush

Empress Wu Zetian (624-705 CE, China's only female emperor who ruled during the Tang dynasty) used 1000 copies of the Diamond Sutra and 1000 copies of the Lotus Sutra to pray for her mother when the latter passed away. In part four of his series of articles on calligraphy, Taiwanese art historian Chiang Hsun looks back at history and is grateful for the tool he has in hand to deliberate, act and to act deliberately. But what is it about holding an ink brush that makes it a rebellious act?

I'm ashamed to say that I've never truly learnt well the rules of calligraphy that Father taught me. Neither have I been able to work harder at mastering the different strokes to the level that Father demanded of me.

It's kind of like the martial artist who lacked a strong foundation in zhan zhuang (站桩, lit. standing like a post), and also how Father would chastise me for "trying to run before you can walk".

When her mother passed away, Empress Wu Zetian used 1000 copies of the Diamond Sutra (金刚经) and 1000 copies of the Lotus Sutra to pray for her.

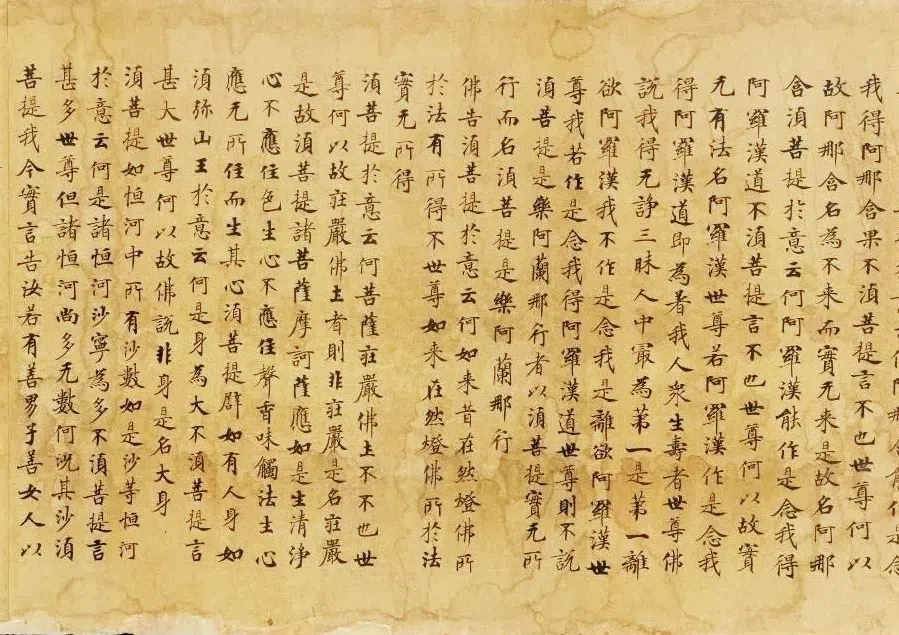

I'm thinking, calligraphy has such a long tradition in Chinese culture. Take for instance how the people of the Six Dynasties period so meticulously copied the sutras. The Lotus Sutra (妙法莲华经), for one, was written in gold ink on indigo-dyed paper. The characters were delicately written in the small regular script, each character as tiny as a fly's head. So neat and tidy were the lettering that one couldn't help but be awed by it.

Empress Wu Zetian (624-705 CE, China's only female emperor who ruled during the Tang dynasty) used 1000 copies of the Diamond Sutra (金刚经) and 1000 copies of the Lotus Sutra to pray for her mother when the latter passed away. Currently, a copy of the Diamond Sutra is kept in the National Library of China. The characters, neat and upright, without being dull or stiff, are still so very awe-inspiring.

Up until the Ming and Qing dynasties, officials wrote their reports to the emperors in the standardised regular script for imperial documents (馆阁体). Those characters looked as if they were printed as well - they were so neat to the extent that made one wonder if they were indeed handwritten.

However, what's in store for the long tradition of calligraphy?

The ink brush was already discovered at the Banpo archaeological site (containing the remains of several well organised Neolithic settlements, carbon-dated to 6700 - 5600 years ago). Based on oracle bone script research, people first wrote on bones or shells with ink brushes, before carving them out with knives.

Would changes in writing tools not affect calligraphy?

So then, what's in store for the ink brush, whose aesthetic form has been passed on for thousands of years?

What's the biggest difference between holding an ink brush now and when the ancient people held their brushes?

Up until the late Qing dynasty and early Republic of China period, the educated always had an ink brush in their hands. The ink brush was their daily writing tool.

However, the fountain pen arrived. The pencil came. And so did the ballpoint pen. Would changes in writing tools not affect calligraphy?

In the 21st century, in this age when even writing is being totally replaced by the computer, how great a mark of rebellion it is to hold an ink brush.

Today, anyone who picks up a brush and grinds ink would be completely different from the people of the past. An action that was most basic and common in the past has suddenly become a unique form of artistic expression.

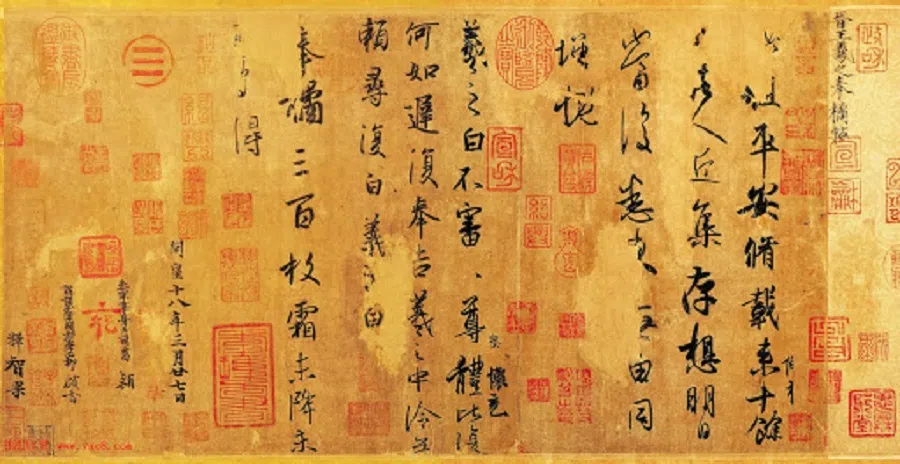

Today, writing with an ink brush can largely be seen as putting up a performance. It is definitely not just a casual note slipped in a box of mandarin oranges meant for a friend with the lines: "Here are 300 mandarin oranges for you. As frost has not descended, I'm unable to pluck more."

Every time I read Feng Ju Tie (《奉橘帖》, Presenting Oranges), I still ponder if I would deliberately attach a casual note written with an ink brush to the gifts I give away. If the answer is yes, then that would really be a very deliberate move indeed. Yet, when Wang Xizhi casually wrote his Feng Ju note back in the day, would he have written it seriously as if he was writing a masterpiece?

Tangled in multiple contradictions, I know that this ink brush that Father placed in my hand not only bids me to carry on with tradition but to rebel.

In the 21st century, in this age when even writing is being totally replaced by the computer, how great a mark of rebellion it is to hold an ink brush. And how great a sense of stubbornness and loneliness there is in fighting against the times?

I only wish to write my own sentences. Having seen all of life's splendours, I want to write about its sorrows, as if I was looking at the brilliant glaze of Song dynasty's Ru ware (汝窑) - a beautiful "clear sky after the rain" type of blue. It is not just a colour - it is a fleeting ray of light. If you see it, you'd be touched to tears. If you didn't, then perhaps you're just not fated to do so.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)