China's crackdown on fake and staged short videos

"Watch! This guy Xiaoshuai is beating up his former wife."

Viewers of short videos on the Chinese internet would be familiar with this setup: no matter how shocking or realistic the footage, as long as it is accompanied by a commentary such as the above, most would be aware that it is a fictional or scripted story. But remove the narration - or replace it with a newsy commentary - and it becomes difficult to assess the authenticity of many clips.

The commentary above was used by Douyin's official account on 30 March over a short video that went viral in late February. At the time, the woman in the video gained netizens' attention as she claimed to be a victim of domestic violence, only to be exposed by local authorities as having staged the video with her ex-husband. The woman's personal account was banned and she was put under administrative detention by the local police for ten days.

Douyin resurfaced this video to introduce its new rule, set to kick in on 1 May: to better manage fake and staged videos and prevent misinterpretations of created content, video creators must prominently state when a work is staged, or face a permanent ban from the platform in the worst case.

But would simply getting content creators to add a label stop the spread of fake stories that could rouse netizens' emotions?

... a man who staged a short clip of himself giving out 3,000 RMB (US$436) as "charity" to the poor villagers in the Daliang Mountains. The stunt was made just to draw traffic, and he later took back 2,800 RMB.

Labelling staged content

According to Douyin's notice on 30 March on the updated rules for creating and publishing staged video content, creators must prominently label works as staged using text including but not limited to "Fake/staged work, for entertainment purposes".

In its notice, Douyin stated that some staged videos lack context and are misinterpreted as real when disseminated. Also, a handful of creators come up with fake news to highlight opposition or conflict, using fictitious characters, plots, locations and props, in order to gain traffic or even earn money.

Besides the staged domestic violence clip mentioned above, another example released by Douyin was of a man who staged a short clip of himself giving out 3,000 RMB (US$436) as "charity" to the poor villagers in the Daliang Mountains. The stunt was made just to draw traffic, and he later took back 2,800 RMB. Following public backlash, the man admitted to staging the video and was put under administrative detention by the local police for 15 days for disorderly conduct, and his Douyin account was banned.

Another example was an ethnic Yi woman who recorded a short clip of her wedding and cooked up a story of how her family accepted a dowry of 300,000 RMB and forced her to get married, just to gain views. She later posted an apology, but her Douyin account was also banned for posting false information.

Douyin's message is clear: if the staged or fictional work is not clearly stated as such, causes misunderstanding among the public and the media and becomes fake news, the platform will take strict action and implement a 30-day or even a permanent ban.

Douyin also stressed that published works must not show content that goes against public order and good practices such as fake charity and sob stories, as well as illegal or undesirable content that is vulgar, violent or discriminatory. However, appeal channels will also be available for creators who feel that they have been unreasonably penalised.

A clear label or not?

Users of the platform and netizens on Weibo expressed support for Douyin's new rules, with many believing that the move was long overdue.

However, some netizens including Jiangning Granny (江宁婆婆) - a team on Weibo that polices the internet - remarked that Douyin should specify a standard label and position, rather than allowing creators to determine what is a "prominent position and clear wording". It said, "Everyone knows that it is too easy to cover up the words 'pure fiction' on the screen."

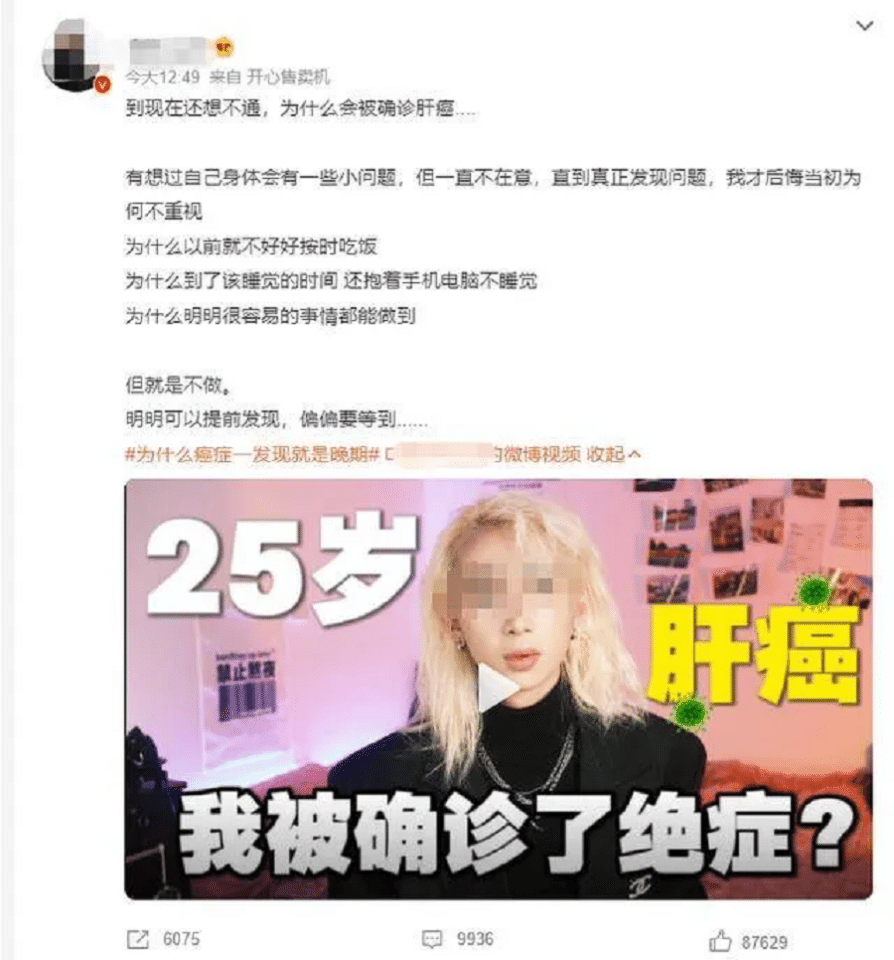

... right at the end of the video, the blogger inserted the text: "This video is purely fictitious."

The concerns of Weibo users are not unfounded. On 30 March, a blogger with over five million followers posted a video on Weibo claiming that he has been diagnosed with liver cancer at the young age of 25. Relevant topics such as "why cancer is diagnosed at such an advanced stage" even became a top search on Weibo at one point.

In the nearly 8-minute video, the blogger shared his experience and feelings about his cancer diagnosis in first-person narration, and overlaid the video with sensationalised texts such as "I want to live so badly". However, right at the end of the video, the blogger inserted the text: "This video is purely fictitious."

The video has since been removed, but it is clear from the discussion among netizens that while the initial comments were full of sympathy and concern for the blogger, netizens began to question and rebuke the blogger instead as more and more people noticed the blink-and-you'll-miss-it disclaimer at the end.

Netizens responded with comments like "Has one's empathy and compassion become so cheap?" and "I can't stand my overflowing compassion". Some even criticised: "Bloggers can really stoop to any level to gain traffic!"

After the incident blew up, the blogger deleted the video that same night and posted two apology letters. He claimed that the fictitious video was meant to serve as a wake-up call, which is why it was presented in the first person. He also said that it was his "oversight" for not mentioning that the video is fictitious from the start. However, netizens did not buy his apology and Weibo temporarily banned his account, prohibited people from following him and suspended his advertising revenue.

This implies that, while Weibo has already put in place relevant regulations, whether the blogger's insertion of the disclaimer in white font on a black background at the end of the video complies with its standard of a "prominent" position, could be interpreted differently by the creator, platform and netizens.

Also, the CAC will clamp down on short videos that challenge bottom lines and violate public order and good morals, such as those proclaiming ugliness as beauty and shame as pride, or those promoting laziness and harm to others.

Crackdown on fake videos

Since last year, there have been calls on the Chinese internet for short video platforms to strengthen the regulation of fictitious content, with some proposing the addition of a unified label. Indeed, Douyin's decision to introduce such new rules is seen as a response to the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC)'s pledge on 28 March to clamp down on fake and staged short videos.

Based on media reports, CAC Vice Minister Niu Yibing said on 28 March at a press conference on the "Qinglang" (清朗, clean and healthy) special campaign that more steps will be taken to comprehensively crack down on malicious and misleading short videos that are produced using fake sets, falsified details, fictitious experiences or other techniques.

Also, the CAC will clamp down on short videos that challenge bottom lines and violate public order and good morals, such as those proclaiming ugliness as beauty and shame as pride, or those promoting laziness and harm to others. It will also comprehensively rectify erroneous and negative short videos that spread the wrong ideas about career, marriage, wealth, history and ethnicity.

Undiscerning audiences the problem?

Analysts generally believe that the CAC's requirements will prompt more short video platforms to introduce corresponding measures. However, some netizens have reservations about the effectiveness of the platform's measures, fearing that the platform, driven by the desire to increase traffic, could end up being "all talk and no action".

If the people and media are not able to discern fake news from real ones, the problem will persist no matter the number of new rules and laws.

On the other hand, Professor Zhang Zhi'an of Fudan University's School of Journalism wrote in The Paper that on top of the regulatory responsibility of short video platforms, mainstream media also shoulders the responsibility of content gatekeeping, public opinion supervision, verifying and refuting rumours to avoid their spread.

The latest Statistical Report on China's Internet Development released in early March found that the number of short video users in China has exceeded 1 billion as of December 2022. Relevant statistics also showed that short video platforms have become the primary news and information source for Chinese netizens.

Aside from the short video accounts of mainstream media, more people are getting their news from we-media accounts that lack professionalism and standard. Netizens are thus worried that solely demanding original content creators to indicate whether their video is fictitious is not enough to stop we-media accounts from intentionally or unintentionally spreading false information when reposting videos.

Although the platform can request creators to indicate if their videos are fictitious, in the era of information explosion where anyone can be their own we-media, platform regulation can hardly keep up with the speed of information dissemination. If the people and media are not able to discern fake news from real ones, the problem will persist no matter the number of new rules and laws.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "真真假假的短视频故事".

Related: Are mainland China tourists discriminated against in Hong Kong? | If 4G = short-form videos, 5G = a different reality | Rejecting their parents' lifestyles, more single Chinese youths are sharing their everyday lives through vlogs | 200 million Chinese are in flexible employment. Is this their choice?