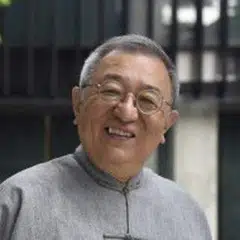

Cultural historian Cheng Pei-kai: My English teacher called me Pei-kai Cheng

Mr Fu Zhou, last name Zhou and first name Fu, was my English teacher in my third year of senior high. Why did we call him Mr Fu Zhou even though he was really Zhou Fu? Simple. He reversed his name order and did that for us too. He wanted us to remember the naming convention in the English-speaking world - first name followed by last name. Indeed when he took attendance, he would call me Pei-kai Cheng. He instructed us to address each other in that way as well to enter the English-speaking frame of mind.

Imbibing a language

During one of our lessons, Hsing I-tien, a model student of our class, asked, "Do we also reverse the name order of historical figures then? Do we call Emperor Li Shimin "Shimin Li", reformer Wang Anshi "Anshi Wang", poet Su Dongpo "Dongpo Su", Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang "Yuanzhang Zhu", and Sun Yat-sen "Yat-sen Sun"?

Our teacher said, "I-tien Hsing, you asked a very good question. That's how we should address them in my class. If you want to master English, you have to first change your mentality. You have to subconsciously enter the ideographic context of a foreign culture. In the past, you lived in the Chinese context and took it for granted that names go by the last name followed by a first name. You hardly even question this fact. But, in the West, names go by first names then last names. This is opposite to your usual way of saying things. By changing something as simple as how you address others, you will be reminded that you have to change your usual ways of expression when learning a foreign language."

After class, some of my classmates gathered around Hsing I-tien, calling him "I-tien Hsing, I-tien Hsing, I-tien Hsing" until he answered.

Then, the class gave a standing ovation to welcome our English teacher.

Mr Fu Zhou was well-loved and respected because he won us over at our very first lesson.

At the start of my third year of senior high, a short middle-aged man walked into our classroom. He looked a little comical and had a crew cut. A three-inch-long beard hung from his chin, a counterpoint to his otherwise clean look. He had a wry smile on his face and a thick book tucked under his arm. Walking up to the rostrum, he placed the book down solemnly and said, "This is Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language. It has over 2,700 pages and defines more than 450,000 English words." He continued, "I am your English teacher, Fu Zhou. Feel free to come up here and pick any word from the dictionary, and I will explain what it means."

We exchanged nervous glances, not knowing what our teacher was up to. That was in the early 1960s. Senior high school students only sat in the classroom and listened to the teacher; nobody dreamed of going up to the rostrum to ask questions. Besides, that was the legendary Webster's Dictionary - what if we picked a word that the teacher could not explain?

Seeing that everyone stayed completely still, Mr Fu Zhou asked, "Who's the class monitor?" I raised my hand and stood up.

He asked, "What's your name?" "Cheng Pei-kai," I replied.

He frowned. "In my class, do not call yourself 'Cheng Pei-kai'. Call yourself 'Pei-kai Cheng' instead." The class burst out in laughter.

Mr Fu Zhou stayed solemn and motioned us to quieten down. He asked me to come forward and pick a random word in the dictionary for him to explain.

Language battles

I opened the legendary book and searched for an unfamiliar word beginning with the letter "A". I wrote the word "archipelago" on the blackboard.

Our teacher said that the word is derived from Greek: "archi" means "main, chief", and "pelago" means "sea". Used during the Greco-Roman period, "archipelago" referred to the "main sea" - the Aegean Sea. Later, it referred to a sea of islands. Now, it generally refers to any island group.

Actually, I did not know the meaning of the word at all. I was stunned by the clear explanation that he gave. He then continued, "Pick another word."

I shook my head and said, "It's okay. I'm sure Mr Fu Zhou knows all of them. Explain to us next time." Then, the class gave a standing ovation to welcome our English teacher.

Mr Fu Zhou's forte was incorporating vocabulary and grammar into everyday conversations, and turning the study of English into a never-ending game. Both of the two classes he taught had to participate in English team battles each week, during which we had to work together to encourage, help, and spur one another on to greater heights. A representative from the winning team would be "congratulated" by the losing team and accept their bows and salutes, while a representative from the losing team would be "insulted" by the winning team and bow to them.

Strange English words, especially those with many syllables, became the code names of our English battles, such as "porcupine", "hippopotamus", "crocodile", and "rhinoceros", such that we were no longer afraid of new words with long syllables. We even invented a new game in which we would see who could form the longest word with the most letters. Mr Fu Zhou was our English teacher for a year, and everyone's English improved tremendously.

A young person recently asked me about my experience learning English when I was in senior high school. I immediately thought of Mr Fu Zhou and of how he had turned the boring study of language into a fun and lively game. That happened over half a century ago. Thank you Mr Fu Zhou, I will never forget your teachings.

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as "複周老師".