The decline of Hong Kong comics: Is politics to blame?

Academic Lian-Hee Wee and researcher Ng Kum Hoon rue the decline of Hong Kong comics, even if classics like Tony Wong’s crime syndicate-related, pugilistic stories live on to today. Politics aside, is it a question of Hong Kong’s youths being too pampered? Or is the industry bent on sterilising itself?

Hong Kong’s comics community was mildly shocked when, around the end of 2023, BL (i.e., boys’ love) comics were apparently removed from the bookstore shelves in Sino Centre, Mongkok. Allegedly, government prohibition was triggered by a police report made when a schoolteacher found underage girls reading such “corrupting” comics. Whether education proceeds best by banning or guiding is a different discussion, but those sensitive to the eroding freedoms are concerned with what spaces remain for creating Hong Kong comics.

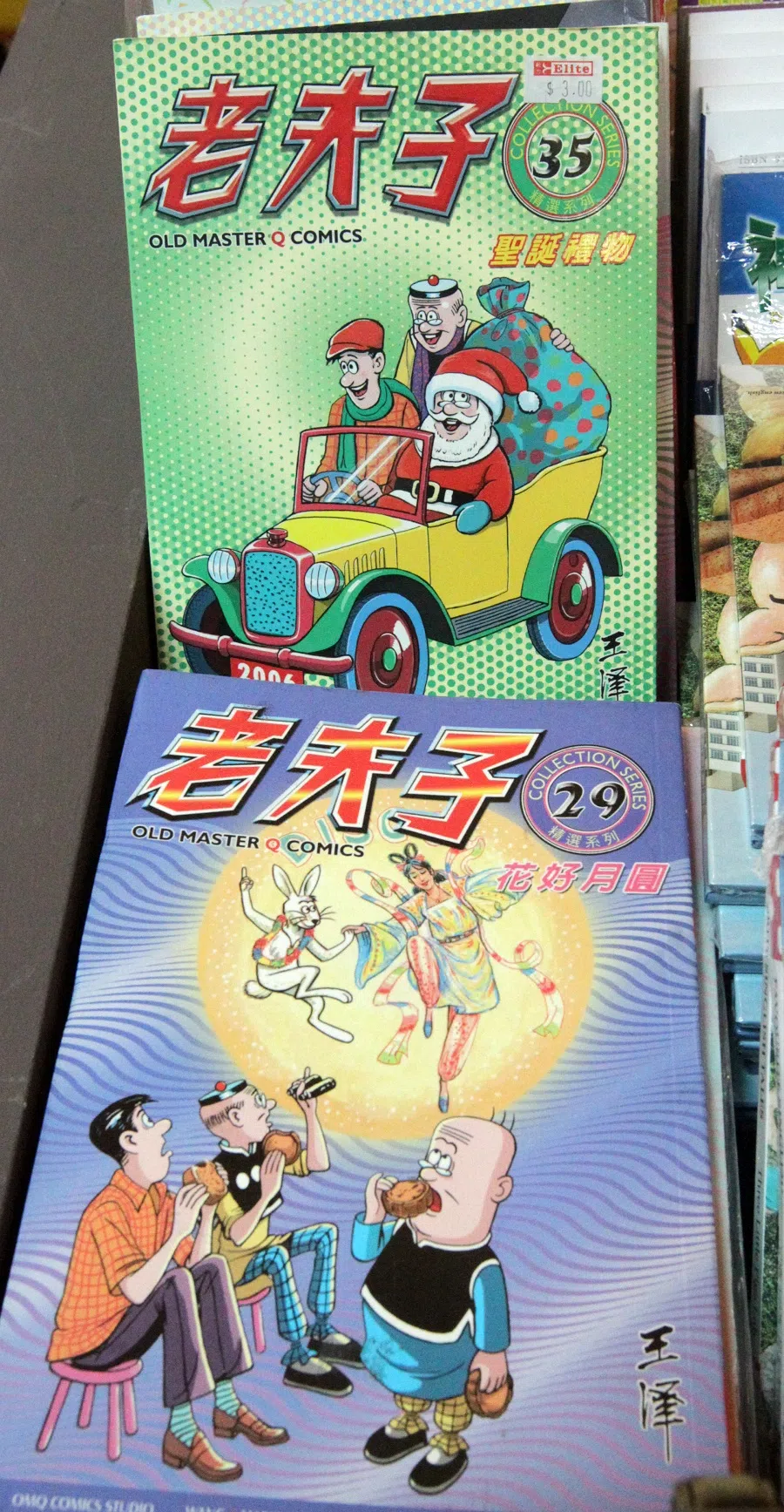

Hong Kong found a place in the comic world early when Old Master Q (《老夫子》) became a staple to the Chinese diaspora globally. Other works from the formative period such as Miss 13 Dots (十三点, first issue 1966) by Lee Wai Chun (李惠珍, 1939-2020) or the 1970s’ Cowboy (《牛仔》) by Wong Sima (王司马, 1940-1983), which grew out of the 1960s’ Father and Son (《契爷漫画》), are less known outside of Hong Kong, although Alfonso Wong (王泽; real Chinese name Wong Kar-hei (王家禧), 1924-2017) would reference Father and Son in his Old Master Q.

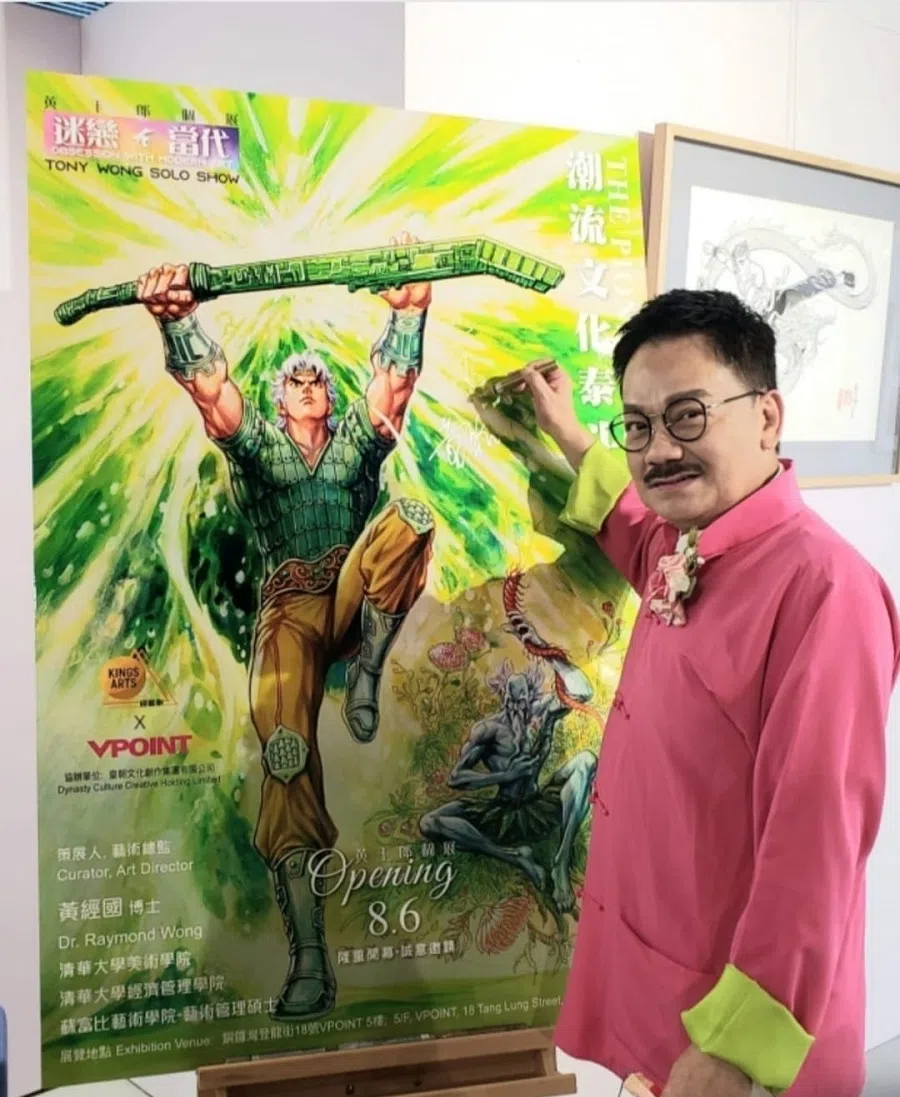

The mention of Hong Kong comics today calls to mind for most people the art started by Tony Wong.

Classic pugilistic stories hold their spot

In 1969, Tony Wong (黄玉郎, 1950- ) released his first issue of Little Rascals (《小流氓》) as a weekly comic that traced long story arcs. This was later renamed Oriental Heroes (《龙虎门》), which continues to this day, albeit through a number of restarts. The latest series after some two or three restarts, New Oriental Heroes (《新著龙虎门》), is at Issue no. 1245 as at March 2024.

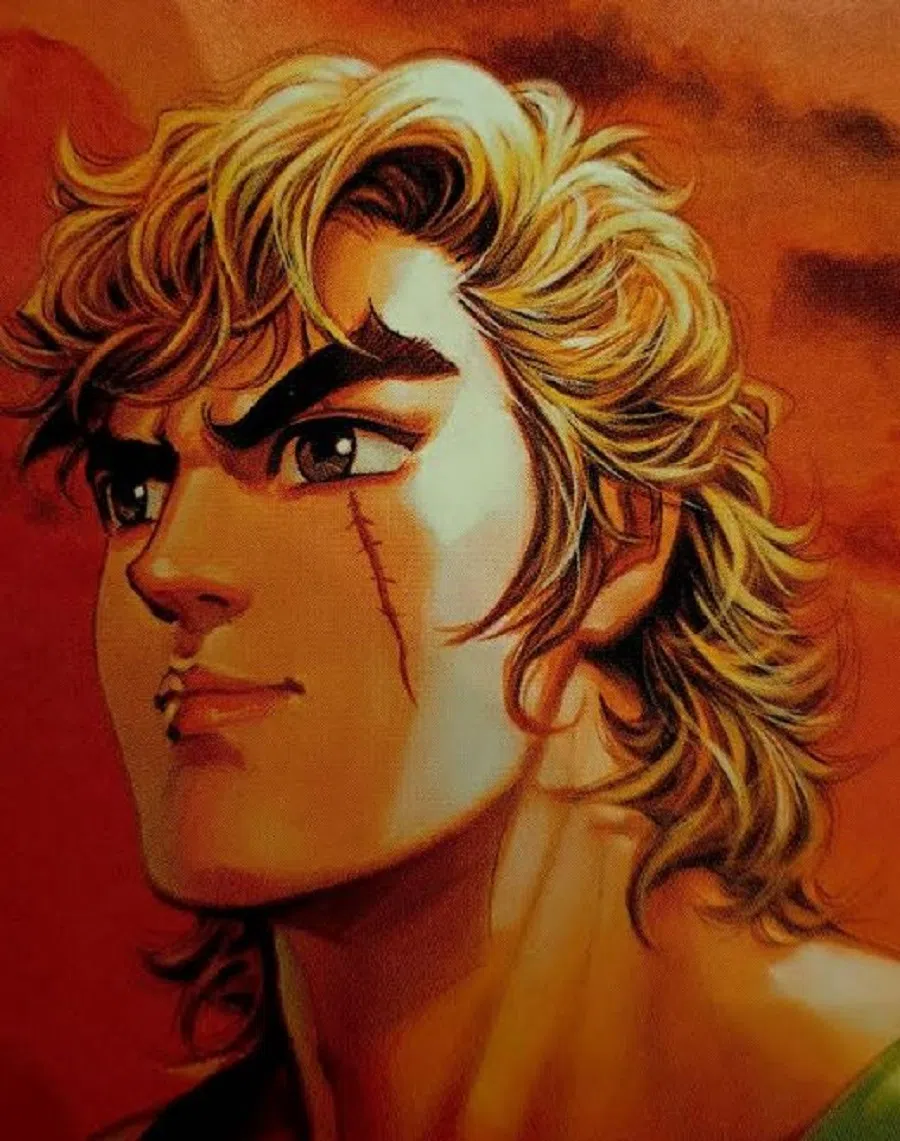

Tony’s works, like that of Alfonso, spread far and wide. His variety of crime syndicate-related, pugilistic stories coupled with harsh, strong muscular line drawings came to represent and even define Hong Kong comics. Practically every male barber shop (probably every clinic and dentist too) in Singapore in the 1980s and 1990s would have copies of such comics, as well as Old Master Q, for waiting customers.

The mention of Hong Kong comics today calls to mind for most people the art started by Tony Wong. It was made possible to a great extent by a host of brilliant artists who were inspired to add numerous titles to this fighting-centred genre.

Not to be easily displaced, Tony went on to produce many other titles as he also cultivated new talents. The most famous among them may be Ma Wing-shing (马荣成, 1961- ), known to moviegoers for the cinematic adaptations of his Storm Riders (《风云》).

Varied genres: animal friends and romance

On a different front, in the early 1990s, Alice Mak (麦家碧) created McMug (麦唛) and other little animals for a four-panel comic Extra Children’s Weekly (《号外儿童周刊》) founded by the Hong Kong actor John Shum (岑建勳, 1952- ), which in 1994 became a children’s insert as Little Ming Weekly (《小明周》).

The leading pigs McMug and McDull (麦兜), together with their kindergarten animal friends, eventually transitioned from panel comics to illustrated stories as Alice collaborated with writer Brian Tse (谢立文 (1950- ), now Alice’s husband), who wrote simple yet moving stories so much needed by stressed-out and disillusioned city folk.

The porcine corpus gained popularity in Singapore after Yung Sai Shing (容世诚) brought publications thereof to the Chinese Studies Department at the National University of Singapore, from which it spread through Malaysian students to their home country and beyond. So successful were these pigs that the Hong Kong government used them as publicity icons.

Less influential, but also from the 1990s was Feel 100%, a romance comic closer to Japanese manga in style, and popular enough to be adapted into movies and a TV series. It ultimately failed to catch on.

To them, Old Master Q is a distant memory and McMug is government propaganda. The genre pioneered by Tony Wong does not seem to draw interest either...

When the sun began to set on the Hong Kong comic industry

The decline of Hong Kong comics really began well before news of the removal of BL at Sino Centre. Concrete and reliable figures are hard to come by, but the industry was certainly selling at least several million copies a year at its peak in the late 1990s. Sales are a mere fraction of that these days.

People have been lamenting the wane (some say “destruction”) since at least ten years ago, and there has been much discussion about the causes. Analysts blame everything from the rampancy of free comics online, the overspecialisation of assistant artists, the diminution of the distribution network, to the limited diversity in the comics ecosystem, none of which are seeing any dead-on, decisive resolution. The situation still looks stark today from our on-the-ground observations.

A quick walk around the newsstands in Hong Kong finds only very few comics on display, mostly the Oriental Heroes type. Even the successful titles mentioned earlier seem to be withering away slowly at best. Among the local youths (men and women aged 17 to 35) we talked to, those who read comics read Japanese manga, and a small handful may read Marvel and DC comics. To them, Old Master Q is a distant memory and McMug is government propaganda. The genre pioneered by Tony Wong does not seem to draw interest either, despite its prolific adaptations of the long popular martial arts novels by Jin Yong (金庸).

In our fieldwork, enthusiasts report that fewer than five outlets carry Hong Kong comics, apart from the regular streetside newsstands, whose number fell from over 2,500 in the 1990s to only 356 in 2020.

ZBFGHK (纸本分格) provides a map of Hong Kong bookstores that carry comics. Of the roughly 30-odd of these on a map made in 2023 for the entire city, we find some already out of business. What remains is a modicum compared to how, back in the early 2000s, there used to be shopping malls largely occupied by comic shops, easily numbering in scores at a single location.

Smiling Plaza at Cheung Sha Wan (长沙湾天悦广场) was one such point of concentration, but its last three shops closed down around the 2010s. Of the few dozen bookstores listed by ZBFGHK, many do not carry Hong Kong comics at all.

In our fieldwork, enthusiasts report that fewer than five outlets carry Hong Kong comics, apart from the regular streetside newsstands, whose number fell from over 2,500 in the 1990s to only 356 in 2020. (We only managed to find these: a warehouse space in Fo Tan, and in Kwun Tong, a shop in Tsz Wan Shan, in Pak Tin and in Mongkok. There was one in Yuen Long, but it seems to have closed down recently. We hope and believe there should be more than five.)

Not necessarily about politics

Titles of the Oriental Heroes type are still being produced, but they also number in the single digits. We have been able to count only three or four artists still working in this genre: Tony Wong, Ma Wing-shing, James Khoo (邱福龙, 1964- ), and Andy Szeto (司徒剑桥, 1965- ). Bookstores that carry comics do not carry the works of these four men as far as we have been able to ascertain.

It is at the newsstands that we find some of the recent issues of their works, as well as reprints of older issues in different binding formats. Back in the heyday, readers used to snap up issues fresh off the press.

Readers interviewed by us now speak of disillusionment because the storylines are uncreative, and the collectible gifts are poor in quality (especially when compared with Japanese manga counterparts). Many of these people, even though often critical of the Hong Kong government in other aspects, categorically dismiss politics as a factor leading to the decline of Hong Kong comics.

Gems online

While the Hong Kong comics scene is severely anaemic in the print format, there is some sustained life in cyberspace, even for the category that does get strangled by politics.

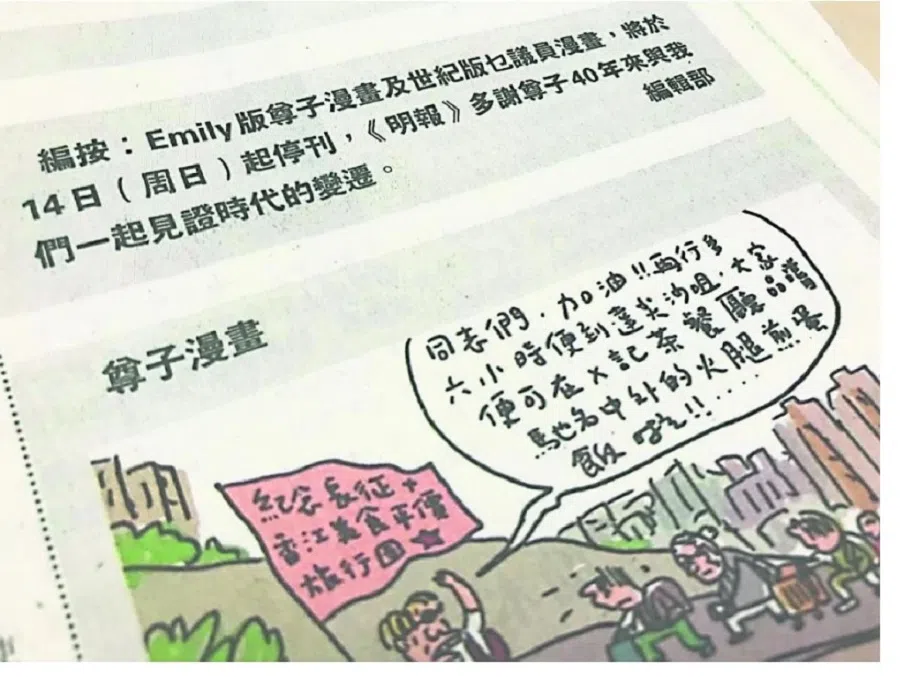

Political commentary is being stifled with lethal intent, as evidenced in recent years by Ming Pao (《明报》)’s termination of Zunzi (尊子, real name Wong Kei-kwan (黄纪钧, 1955- )’s 40-year-old pictorial column, as well as the self-shutdown and self-exile of Justin Wong (黄照达) and Brian Chan (the frog-themed artist who went by Baishui (白水)).

... are Hong Kong’s youths too pampered? Or is the industry bent on sterilising itself? Perhaps this is what we should look at above all else.

Even comic artists who only touch on social and political subjects have expressed fear because they “don’t know where the red line is”. Nevertheless, there are caustic commentators like Hong Kong Guy and Oneaguy who still thrive on online channels.

Among cartoonists who do “safer” art, the likes of Chao Yat (草日, real name Leung Chung-kei (梁仲基), 1968- ) and Cuson Lo (卢炽刚, 1972- ) also produce pieces mostly through social media like Instagram and Facebook. Some of them sometimes publish their works physically as a collection, but these are very few.

Across the spectrum of artists surveyed here, we see ageing without succession. But there are actually young individuals who aspire to draw. We have, for example, met Kennix Chow, 27. Kennix struggles to make ends meet while trying to develop herself as a comic artist and storyteller. Employment is stifling because of low pay, little hope of getting a by-line for her work, and constrained space for creating.

To be fair, the government promised a hands-off approach in the Hong Kong Comics Support Programme, which has completed its second round in 2023. You have to be a company to play though. The last two rounds supported 30 entries, each winning HK$200,000 (US$25,600) for publication and a number of fee waivers at comic fairs.

So, are Hong Kong’s youths too pampered? Or is the industry bent on sterilising itself? Perhaps this is what we should look at above all else. After all, creativity has always found a way in the most trying of times, except when no one is allowed to carry on the torch.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)