Did H&M kowtow to China? The Vietnamese think so and Hanoi is encouraging online nationalism

H&M, the global-trotting purveyor of fast fashion, has in recent times come under official pressure in Vietnam, thick and fast. The fount of the controversy pertains to the Swedish firm's position - still unsubstantiated as yet - on China's divisive nine-dashed line claim to the South China Sea.

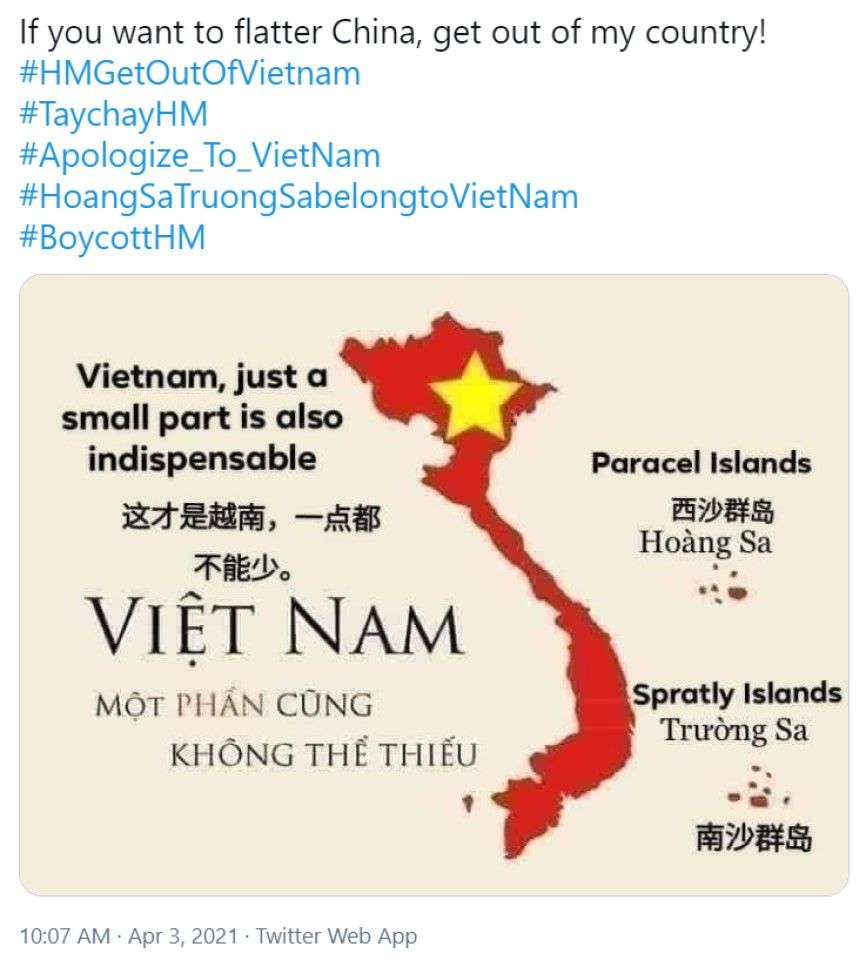

H&M has been facing a growing uproar and boycott call from social media users in Vietnam who have accused it of capitulating to Beijing to use a map that contains the controversial nine-dash line. The claim includes large swathes of the South China Sea and is vehemently opposed by Hanoi.

The H&M saga began on 2 April, when the Shanghai municipal administration asked H&M to correct a "problematic map of China" on its website. The official request comes in the wake of another kerfuffle in China after the Swedish fashion retailer had voiced concerns last year about alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang province.

Although the request by the Shanghai administration stopped short of saying what the problem with the map entailed, in Vietnam, it was first quickly framed as a sign that H&M had endorsed the nine-dash line after kowtowing to China.

Many Facebook groups in Vietnam have either implicitly or publicly adopted a pro-government stance. Concurrently, they peddled the interpretation that H&M supported the nine-dashed line claim on the night of 2 April, and called for a boycott against H&M. This narrative reverberated through social media. Before long, many of Vietnam's state-run news outlets also swung into action.

The saga is redolent of another wave of online nationalism that declared Jackie Chan, a martial arts film star, persona non grata in Vietnam in November 2019. Then, Chan had to scrap his Vietnam visit after eventually bowing to an online backlash that alleged that he had spoken in support of the nine-dash line.

Hanoi quick to capitalise on nationalist sentiment

Taking place against the backdrop of Beijing's assertive behaviour in the maritime arena and maritime muscles-flexing moves, both cases sketch out a strikingly similar pattern: there is no compelling evidence to substantiate allegations that H&M used a map that contains the nine-dash line, or that pro-Beijing Chan explicitly supported it.

But still, after social media posts lit the flames, internet users pounced in. The Vietnamese authorities used this pretext to eventually issue statements that dismissed China's nine-dash line and telegraph messages to a broader international audience. The backlash against H&M is the latest testament to how increasingly adept Hanoi has become at exploiting and harnessing the powerful confluence of rising nationalist sentiment and social media.

The geopolitical context surrounding both the Jackie Chan and H&M cases offers a glimpse into why Hanoi sought to make the most of the nationalistic opposition.

In 2019, just two days before Chan cancelled his charity visit, a Vietnamese deputy foreign minister at a conference floated the possibility of legal action against China. The statement was made in the context of a simmering standoff in which a Chinese oil survey vessel had entered Vietnam's exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea months earlier.

In recent months, China's foreign minister Wang Yi has visited all Southeast Asian countries but Vietnam. This in itself is a glaring omission.

Context of worsening Sino-Vietnamese relations

Similarly, the H&M episode is taking place against the backdrop of souring Sino-Vietnamese ties.

In March, 220 Chinese ships were reported to be anchored around the Whitsun Reef, part of the Spratly Islands, a move that has drawn strong protests from Vietnam. In what appears to be a high-level diplomatic snub, Vietnam was not invited to a high-profile regional meeting hosted by Beijing in Fujian late last month. The meeting brought together the foreign ministers from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore to discuss the political chaos in Myanmar. In recent months, China's foreign minister Wang Yi has visited all Southeast Asian countries but Vietnam. This in itself is a glaring omission.

The H&M saga has also culminated in a hardened position by Hanoi. On 8 April, a statement by Vietnam's Ministry of Foreign Affairs reiterated, without naming the Swedish retailer, that companies operating in Vietnam must comply with laws that forbid content that undermines the country's maritime sovereignty in the South China Sea.

But the [anti-China] protests later morphed into deadly riots, taking a heavy toll on other businesses from South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan. They were mistaken for Chinese firms.

The stakes are high for Vietnam, however. If Hanoi encourages online nationalism, it also needs to prevent it from spiralling out of control. In 2014, China's placement of an oil rig in Vietnam's exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea triggered a widespread backlash. In calibrating its multi-pronged response, Vietnam allowed the public to vent their spleens on social media and the comment sections of state-run news outlets. Such sentiment led Vietnamese patriots to organise anti-China street protests, a move that at times received the tacit green light from the authorities. But the protests later morphed into deadly riots, taking a heavy toll on other businesses from South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan. They were mistaken for Chinese firms.

Were they pushed to choose between China and Vietnam, few companies would be able to afford to resist the lure of the Chinese market.

Faced with such complex challenges, corporate brands leery of getting caught in a geopolitical crossfire may try to walk a tightrope. But when it comes to territorial disputes, Western companies have become inured to toeing the Chinese line. Were they pushed to choose between China and Vietnam, few companies would be able to afford to resist the lure of the Chinese market. For Vietnam, the challenge is to be able to exploit the promise - and peril - of social media.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.

Related: BBC vs CCTV's Xinjiang: Which is the real Xinjiang? | The fight that never ends: Why are China and the West now fighting over Xinjiang cotton? | 'Countering sanctions with sanctions': Where China's confidence comes from | Facing the ire of 1.4 billion Chinese consumers: Multinational companies cottoning on to supply chain risks