Does China have a food security problem?

A Chinese idiom holds that "people regard food as their heaven" (民以食为天). For thousands of years, safeguarding food security has been a top priority for the Chinese rulers, and this remains so today. Over the past year, top Chinese leaders have often publicly stressed the importance of food security. For instance, in April 2021, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared that "food security is an important foundation for national security".

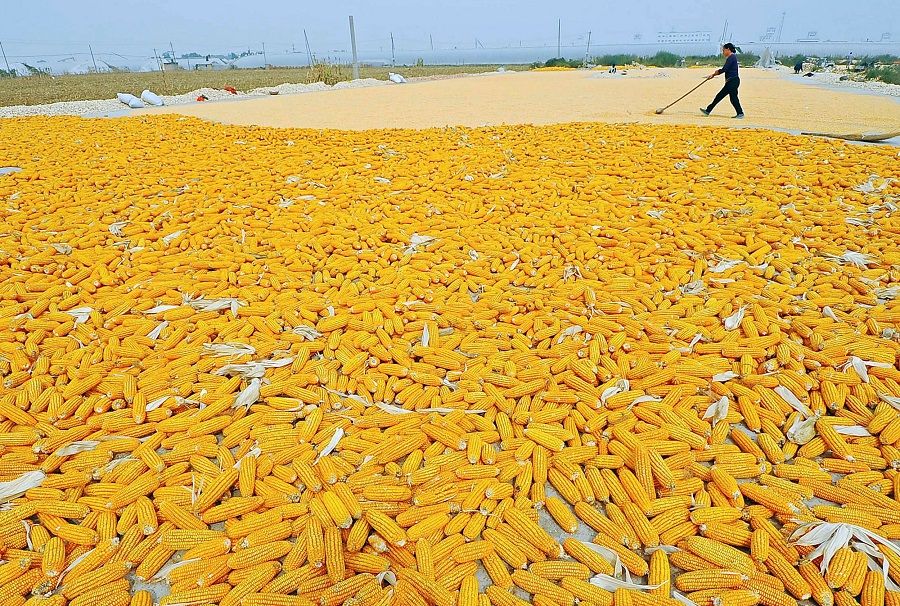

For decades, to safeguard its food security, China has adopted a policy of achieving self-sufficiency in grain, influenced by the painful history of periodic famine and out of the distrust towards the international market during the Cold War era. However, since the late 2000s, as its domestic grain production fell increasingly short of the country's rising demand driven primarily by feed grains, achieving self-sufficiency in grains has not only become economically but environmentally unsustainable as Chinese consumers move away from a grain-based diet.

In response, in December 2013, China took a significant step to reform its food security strategy and a dual approach to food security based on "domestic supply with moderate imports" was introduced.

China's dual approach to food security

This dual approach can be summarised as follows: achieving self-sufficiency in staples (rice and wheat) and key protein sources (particularly pork) while relying on the international market for supplies of non-staples, particularly feed grains.

... in recent years, China has moved ever closer to allowing the commercialisation of genetically modified (GM) crops, such as corn and soybeans.

Boosting domestic production

To maintain high domestic output for staples, China has introduced very strict rules regarding farmland protection and usage. Conversation of farmland for commercial development has been strictly regulated and switching from grain production to cash crops has been discouraged, particularly in major grain-producing provinces.

Furthermore, almost all policies related to agricultural and food security have highly emphasised agricultural science and technology, which is considered vital to boost domestic grain production. For instance, amid the 2007/2008 global food crisis, China introduced the National Food Security and Long-Term Planning Framework (2008-20), which anticipates that the future increases in agricultural production yields will primarily rely on the successful application of agricultural science and technology. The plan suggests that the country should support and develop research in a number of key agricultural technologies to achieve breakthroughs in grain yields.

Beijing has attempted to boost its food supply by expanding its agricultural operations overseas and exerting control over all stages of global food supply chains.

In addition to heavy investment in hybrid seeding technologies, including the well-known hybrid rice, in recent years, China has moved ever closer to allowing the commercialisation of genetically modified (GM) crops, such as corn and soybeans. Lastly, China has built up a massive strategic grain and food reserve system to buffer against potential disruptions to its food supply.

A comprehensive international strategy

Internationally, China has adopted a global agricultural policy to meet the rising domestic demand for food. This outward-looking food security approach has four major aspects. Firstly, Beijing plans to import more food from the international market. Secondly, as its agricultural and food imports soar, China has been following a diversification strategy not only in terms of food-importing countries but also in the variety of crops and food products, agricultural trade routes, and modes.

Thirdly, Beijing has attempted to boost its food supply by expanding its agricultural operations overseas and exerting control over all stages of global food supply chains. Thus, China has become a significant player in overseas agricultural investment and related infrastructures, particularly under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Lastly, China aims to play a more substantial role in shaping global food governance. In its 2019 "Food Security in China" white paper, Beijing stated that it would actively engage in international and regional food security governance.

... China's water resources have serious water quality issues as well as quantity issues owing to highly uneven spatial distribution.

Challenges and China's policy responses

At present, however, Beijing's dual approach to food security is facing major challenges, both domestically and internationally.

Land and water issues

China's multi-faceted land problems are the first major challenge to the country's food security. In addition to the fact that China has very limited arable land, especially on per capita terms, its farmland has become severely degraded and polluted, owing to industrial activities and intensive farming. Even worse, China's farmland is also highly fragmented due to the household responsibility system (HRS).

In recent years, China has stepped up efforts to scale up and clean up the country's farmland through reforms in its rural farmland legal rights to encourage land consolidation and the introduction of farmland restoration, crop rotation and fallow land systems to improve farmland quality.

Similarly, China's water resources have serious water quality issues as well as quantity issues owing to highly uneven spatial distribution. Plentiful water is vital for grains to grow; however, the northern provinces (excluding Tibet), which produce over 50% of the country's grains, have only 16.5% of China's freshwater resources. The three provinces in China's Central Plain (Henan, Shandong, and Hebei), with only 2% of the country's water resources, produced 23% of China's grain.

In these regions, reliance on groundwater has resulted in overdraft conditions and adverse environmental effects. Since the late 1990s, groundwater overdraft has become one of China's most serious resource problems. To address the water problems, in addition to heavy investment in water-saving technologies and improving agricultural irrigation systems, China is spending trillions of RMB on mega projects such as the South-North Water Diversion project alongside damming the country's rivers to boost the country's water supply.

Many Chinese farmers are switching to cash crops or are even leaving their land idle, posing major threats to the country's grain supply.

Unsatisfatory grain production

Another major challenge facing China's efforts to boost domestic grain production is the farmer's lack of incentives for grain production. Given its agricultural factor endowments, China does not have a comparative advantage in producing land-intensive crops, particularly in grains. Not only is China's grain farming far less competitive when compared to that of major international exporters such as the US and Canada, but grain production also offers farmers far fewer returns than farming cash crops such as fruits and vegetables.

Consequently, farmers have far fewer incentives to produce grains. Many Chinese farmers are switching to cash crops or are even leaving their land idle, posing major threats to the country's grain supply. A vast amount of financial subsidies are provided annually to farmers to encourage grain production to address this problem. In May 2022, China pledged US$1.5 billion in grain farmer subsidies to offset soaring production costs. However, China's massive agricultural subsidies have angered its major trading partner, the US, one of the major factors behind China-US trade disputes.

Opposition to GM food

Resistance to genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is another massive challenge. Recent moves from the Chinese government suggest that approval for the commercial planting of GM crops such as corn and soybeans may soon be given despite public opposition to GM food. As China's top policymakers have urged progress in biotech breeding, it appears that the Chinese government will, at some stage, approve new regulations to allow the planting of GM seeds to boost the domestic production of these crops.

... the low public acceptance of GMOs remains the biggest obstacle to the development of GMOs.

However, since 2009, domestic anti-GMO movements have gradually turned GMO issues into one of China's most controversial and sensitive topics. Even though the top leaders, including Xi Jinping, have expressed support for GMOs in China and stressed the importance of ensuring GMO safety, the low public acceptance of GMOs remains the biggest obstacle to the development of GMOs.

As the biggest food exporter globally, no other country can match US agricultural imports (especially for grain), and no other country in the world can be as reliable as the US in supplying agricultural products to China.

Dependence on the US

Internationally, China's global quest for food security is also facing multiple challenges. The first is that seeking further diversification away from the US is not an easy task. Given China's rising food imports and growing tensions between China and the US, China has been pushing for further diversification of agricultural imports to avoid dependence on the US. However, the challenge is that the US role as China's largest food supplier cannot be easily replaced. As the biggest food exporter globally, no other country can match US agricultural imports (especially for grain), and no other country in the world can be as reliable as the US in supplying agricultural products to China.

As China's relationships with major Western food exporters have deteriorated, Beijing has continued to diversify its agricultural imports, looking to countries supportive of the BRI. Notably, the Chinese government's emerging "Food Silk Road" aims to diversify food imports from many regions worldwide, including Africa and Latin America.

To date, China has signed over 100 agricultural cooperation agreements with BRI countries. As part of the Food Silk Road, China also attempts to reconstruct global food supply chains through overseas free trade agreements, infrastructure investments, and farmland acquisitions in foreign countries.

Unfortunately, the immediate and long-term effects of the Ukraine-Russia war have cast further uncertainties over the reliability and sustainability of the Food Silk Road. The outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which has disrupted supplies from Ukraine and wheat export bans on Russian exports, will undoubtedly affect China's wheat diversification efforts. And Beijing's push to secure more wheat supplies during the war, in the face of economic sanctions placed by many countries on Russia, may bring even more uncertainties to the global wheat market.

However, alongside the agricultural import diversification efforts and China's growing agricultural investment overseas, the "China threat to global food security" narrative has been revived. On the one hand, some blame Chinese growing food imports, particularly its stockpiling, for partially causing the global food crisis. On the other hand, some accused China of being a "land grabber" or neo-colonial power, which had embarked on a state-sponsored quest to lock up vast tracts of land in developing countries of Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Central Asia to grow food to feed itself.

... the Chinese central government's interest in "future foods" including alternative protein (such as lab-grown meat) to bolster self-sufficiency has increased.

China's additional measures to address food security concerns

Facing these challenges, China has taken a wide range of additional policy measures to safeguard its food security.

Preventing food waste and creating future foods

The first is the national campaigns to reduce domestic food demand. Although China has seen consecutive bumper harvests, Chinese leaders have frequently pointed out the necessity of preventing food waste. In 2013 and 2020, President Xi launched nationwide campaigns against food waste, supported by the 2021 national "Anti-Food Waste Law" and, soon, a new food security law.

Next, the Chinese central government's interest in "future foods" including alternative protein (such as lab-grown meat) to bolster self-sufficiency has increased. In January 2022, China's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs released the Five-Year Agricultural Plan (2021-2025), which included a section on "creating future foods" for the first time. This section referred to lab-grown meats and plant-based eggs as examples of future foods that will be part of China's blueprint for food security.

In March, President Xi encouraged agriculture officials to seek protein sources outside of the traditional livestock industries to help safeguard China's food supply. As part of this, Xi urged officials to create cell-cultured, plant-based, fermented animal protein, noting that innovation is key to China's food security and sustainable development. Although regulatory approval for the commercial sale of cultivated meat in China has not yet been given, other alternatives like plant-based meat are already produced and sold in China.

Improving crop technology and mariculture

Further seeking to increase domestic production, the Chinese government has announced plans to support greater use of technology to stabilise crop yield and ensure supplies. Earlier this year, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs announced that technological services and advanced technology could be promoted to help farmers increase production.

As part of this, five provinces are set to receive technical guidance from the ministry. At the same time, online training courses have been offered to over 800,000 people through the National Agricultural Technology and Education Cloud Platform.

... unless the fish feed issue is resolved, the rapid development of China's "Blue Granary Plan" could continue to exert pressure on the wild fish stocks of the country and beyond.

Moreover, faced with rising demand for high-quality animal proteins, growing feed challenges and acute farmland and water shortages, China has been embracing the concept of "Blue Granary", which aims for a better utilisation of the "blue territories", primarily marine fishery and mariculture (or marine ranching).

In November 2017, the Ministry of Agriculture promulgated the "National Mariculture Development Plan (2017-2025)", which indicates that by 2025, China will build 178 national-level demonstration marine ranches. The target was raised to 200, according to the 14th Five Year plan for fishery development, which was released in 2022.

However, unless the fish feed issue is resolved, the rapid development of China's "Blue Granary Plan" could continue to exert pressure on the wild fish stocks of the country and beyond.

Stressing political importance of food security

In addition, greater emphasis has been placed on stressing food security as a political responsibility for both central and local governments. In April 2020, the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party made food security one of its six guarantees to the public in response to the pandemic and disruptions to global food supply chains. President Xi Jinping has also called for further efforts to safeguard grain acreage and protect farmland to encourage domestic production.

In December 2021, amid the growing concerns about the impacts of Covid-19 on its food supply and the worsening relations with the country's major economic partners, Xi Jinping, the Chinese president, while addressing a meeting of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, emphasised that "ensuring the supply of primary products is a major strategic issue and the Chinese people must have firm control over their food supply" and highlighted that "party and government officials must assume the same responsibilities" in safeguarding the country's food security. Also, policies were introduced in recent years to make both the party committees and government agencies at local levels responsible for agriculture and food security.

As far as the current global food crisis is concerned, given China's relatively smaller exposure to the global market and its huge food reserve system, there appears to be no substantial risk, especially in the short run.

Effectiveness of food security measures and global implications

With the rapidly surging global food prices, there are growing worries in China regarding the status of the country's food security. As far as the current global food crisis is concerned, given China's relatively smaller exposure to the global market and its huge food reserve system, there appears to be no substantial risk, especially in the short run.

Nevertheless, global food shocks will certainly push up the domestic food prices, mainly through feed supplies, and China will inevitably face huge international pressures and criticism as more developing countries suffer from food crises. China's stockpiling efforts were already being accused of being one of the reasons behind rising food prices globally. In the long run, China's food security will be contingent upon the effectiveness of these measures.

As it is, as China's top leaders repeatedly stress the importance of controlling their own rice bowl while also attempting to diversify the country's imports amid continued disruptions to global supply chains arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, there are concerns over how successful China's food security measures are.

For greater domestic agricultural production, the effectiveness of some measures, such as establishing red lines for farmland, which rely on the support of local governments, are well within the central government's reach. However, the effectiveness of other measures to boost food security at home is far less certain.

Like many other countries worldwide, climate change-induced extreme weather events will continue to challenge Beijing's food security ambitions. Over the past decades, severe flooding and droughts have increased in intensity, duration, and frequency, causing enormous damage to China's agricultural production.

Fluctuation in China's domestic food production will be a key factor shaping the global food market and China's attempts to diversify its agricultural imports are revamping global food supply chains.

Extreme weather events also impact China's ability to import greater quantities of agricultural products from current and new markets, meaning that its growth potential remains limited in the short term. For example, this year's prospects of a record Brazilian soy crop were shattered by adverse weather that delayed harvests, with exports far below initial estimates. This, combined with the absence of Ukrainian and Russian exports due to the ongoing war, lingering pandemic, and increasing food export bans, could easily result in a reduced availability of staples, creating additional challenges to China's diversification efforts, simultaneously expanding the country's vulnerability to trade tensions and supply shocks.

As the largest agricultural producer, leading agricultural importer and a major agricultural exporter, Chinese efforts to address its food security concerns are not only of vital importance to the 1.4 billion Chinese people but also have far-reaching impacts globally.

China's mode of agricultural modernisation, regardless of the success or failure, will shape the global discourse on agrarian reform. China's embrace of GMOs could have substantial spillover effects across other countries. Fluctuation in China's domestic food production will be a key factor shaping the global food market and China's attempts to diversify its agricultural imports are revamping global food supply chains.

Related: Pandemic, floods, locusts and shrinking farming population: Will China suffer a food crisis? | Will China plunge into a food crisis? Officials say no | Chinese farmers struggling with excessive anti-epidemic measures | China's changing diet: Should the world be alarmed? | Food scraps and empty new apartments: China's fight against wastage | The impact of the Russia-Ukraine war on the Chinese economy