How do the West’s concerns about China’s overcapacity stack up?

(By Caixin journalists Wang Liwei, Yu Hairong and Denise Jia)

As German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen concluded their visits to China earlier this month, a central theme became clear: the nation’s industrial overcapacity, which sits near the worst levels in the last decade, looms large in the minds of foreign leaders and policymakers.

The question is, are such worries valid?

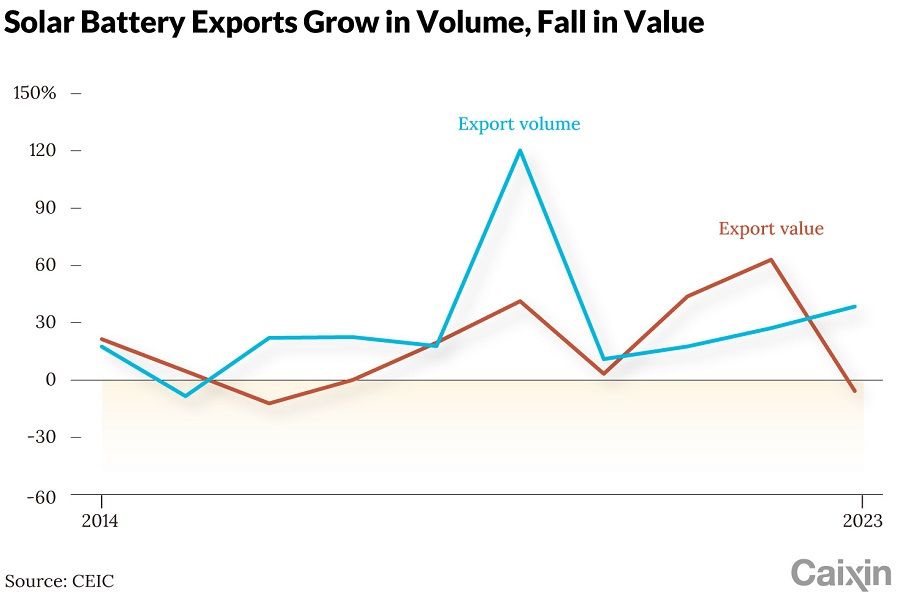

Each expressed concerns on behalf of the US and Germany, who are China’s biggest trading partner and world’s third largest economy respectively, about Beijing’s overproduction and steep increase in exports of products such as solar panels, new energy vehicles (NEVs) and batteries.

In all of these sectors China now comfortably leads the world in terms of manufacturing, but are where the US and Europe have traditionally held competitive advantages.

The discord comes at a time the diplomatic dynamic between China and major Western powers is increasingly characterised by a delicate balance of cooperation and competition. For example, Washington seeks Beijing’s cooperation on anti-drugs policy, climate change and artificial intelligence, despite escalating China export curbs on microchips, seen as crucial to national security.

Meanwhile, Europe has sought greater market access for its products in China and for Beijing to pressure Russia to withdraw its forces from Ukraine, even as it conducts an anti-subsidy probe into imports of Chinese electric vehicles (EVs).

In response, China’s Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao earlier this month slammed accusations from the US and EU that China’s overcapacity in the EV industry benefited from excessive state subsidies as “groundless”.

In other discussions with Western leaders, Chinese officials have emphasised the importance of a pragmatic, market-driven approach to address capacity concerns, advocating for an understanding that accounts for the natural fluctuations of supply and demand.

“Overcapacity is a feature of China’s economic model, not a bug.” — Jacob Gunter, Lead Analyst, Mercator Institute for China Studies

There is support for this argument.

“Overcapacity is a feature of China’s economic model, not a bug. In that sense, it is no surprise if Beijing argues that overcapacity is a natural development driven by sudden shifts in supply and demand which occurs when industries emerge at Beijing’s direction,” said Jacob Gunter, lead analyst at the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies, in a report earlier this month.

“With little material pushback from the US and EU for earlier rounds of overcapacity, which generated cheap goods for our consumers and manufacturers, Chinese officials may be caught off guard that this is now an issue,” he said.

Indeed, overcapacity is not new in China. Most recently it emerged in the middle of the last decade, when traditional industries such as steel and aluminum saw a major capacity build-up after government stimulus was directed at infrastructure and property construction following the 2008 global financial crisis. At that time, it was mainly dealt with by mandatory factory closures.

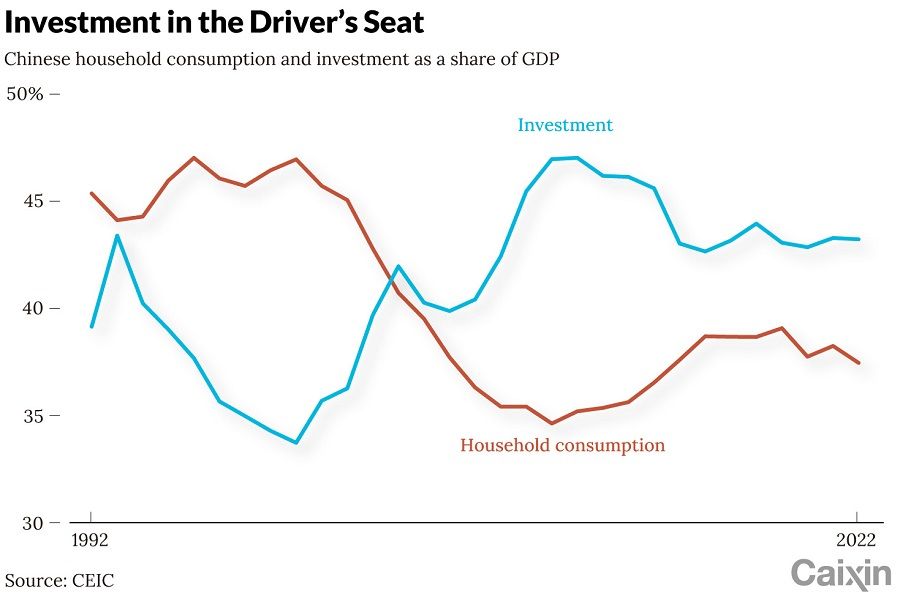

However, this time officials and experts suggest that the lack of domestic demand is the main issue, and therefore the government should increase investment in education, health care, social security and other areas of people’s livelihood so as to boost consumer spending.

“China’s March 2024 National People’s Congress (NPC) meeting set an explicit focus on industrial policy favoring high-technology industries, with very little fiscal policy support for household consumption,” said the Rhodium Group in a report last month. “This policy mix will only compound the trade impacts of China’s growing state-supported industrial capacity.”

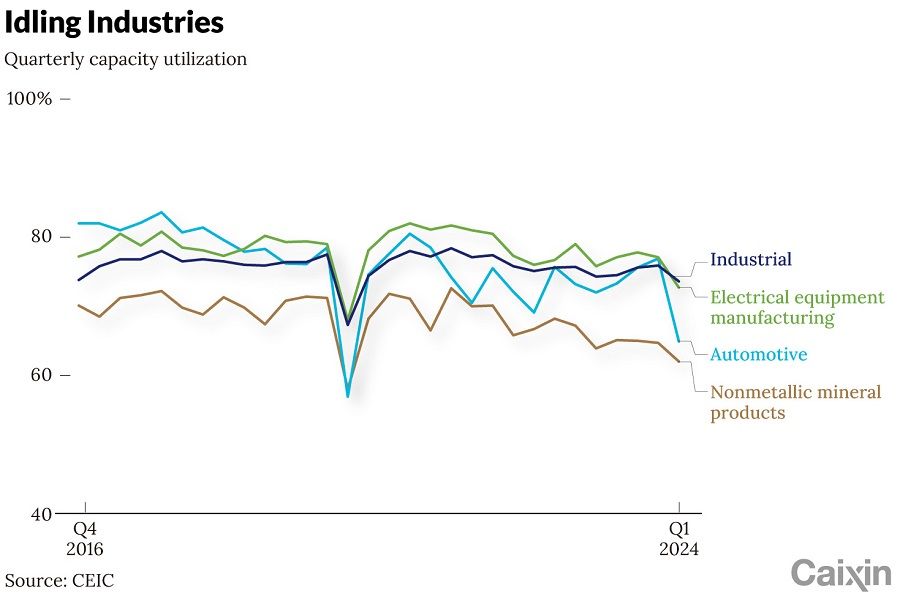

Declining capacity utilisation

Capacity utilisation, a key economic indicator reflecting the ratio of actual output to potential production capacity, offers insights into market demand, supply and the broader economic sentiment.

Generally, a high utilisation rate may signal capacity shortages and inflationary pressures, whereas a low rate suggests underused capacity, hinting at potential economic inefficiencies or unreasonable capacity structure. This metric varies by industry and country, depending on specific economic conditions and developmental stages, with no universal standard for optimal levels.

In the first quarter of 2024, China reported a concerning dip in industrial capacity utilisation to 73.6%, the third lowest since records began in 2013, only higher than 69.7% in the same period in 2016 when China initiated supply-side structural reform and 67.3% in the first three months of 2020 during the pandemic, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics.

... opinions are divided on whether the new energy vehicle (NEV) sector, which has been one of the main targets of complaints from Western governments, is at risk of overcapacity...

The downturn was especially pronounced in key sectors such as automotive manufacturing and electrical equipment linked to the new energy sector, experiencing sharp declines of 7.1 and 3.1 percentage points, respectively, compared to the same period last year, the data showed.

“The under-utilisation of production capacity in China is concerning in its own right for foreign policymakers and businesses,” said the Rhodium report. “It incentivises firms to lower their prices in search of a market for their excess capacity,” which in the past, has led to global over-supply, price declines, weak profitability, bankruptcies and job losses, it said.

But opinions are divided on whether the new energy vehicle (NEV) sector, which has been one of the main targets of complaints from Western governments, is at risk of overcapacity, with some asserting it merely shows robust growth opportunities and no apparent surplus when compared internationally.

However, concerns have been raised about the sector’s chaotic competition, blind expansion, and redundant projects, which some officials suggest might foreshadow an impending oversupply, according to Lu Feng, a professor of economics at the National School of Development at Peking University and an expert on the sector.

Recent data from a major supplier to several Chinese automakers shows a steady decrease in their capacity utilisation, plummeting from about 62% in 2017 to approximately 48% in 2023.

This downturn highlights a concerning trend, with only 20 carmakers maintaining a utilisation rate above 60%, while 19 operate between 30% to 50%, and a significant number, 36 companies, functioning below 30%, according to the data from the supplier.

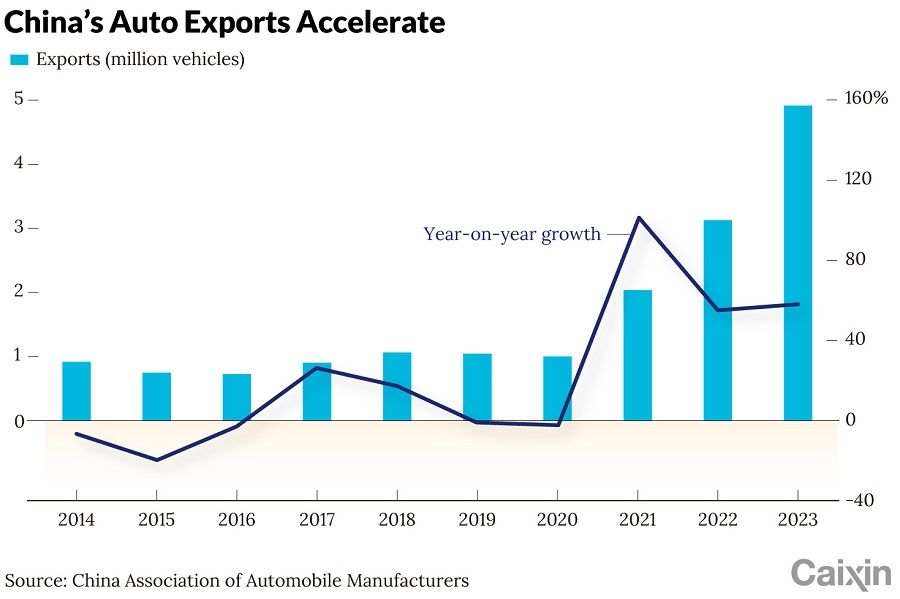

Concerns about overcapacity in the sector led to the European Commission lunching an anti-subsidy investigation in October against Chinese EV makers, targeting BYD Co. Ltd., Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co. Ltd. and SAIC Motor Corp. Ltd., three of China’s biggest automakers. The US has also introduced restrictive policies on China’s EVs and batteries.

According to an October report by the commission, the share of EVs from China sold in the EU recently jumped from less than 1% to 8%, with this share possibly soaring to 15% by 2025. European carmakers could collectively lose more than 7 billion euros in annual net profit by 2030, according to a May report last year by German financial services company Allianz SE.

... frequent technological updates and the phasing out of outdated capacities further complicate assessments of what constitutes a reasonable capacity utilisation rate.

The shift from traditional fuel vehicles has buoyed the significant growth in demand for chips, NEVs and batteries, emphasising that these sectors are at the forefront of technological innovation, said Lu. But he cautioned that determining excess supply in these rapidly evolving industries requires careful consideration of their unique dynamics.

Factors such as price cuts might stem from increased market competition or scale efficiencies, rather than mere oversupply, said Lu. Additionally, frequent technological updates and the phasing out of outdated capacities further complicate assessments of what constitutes a reasonable capacity utilisation rate.

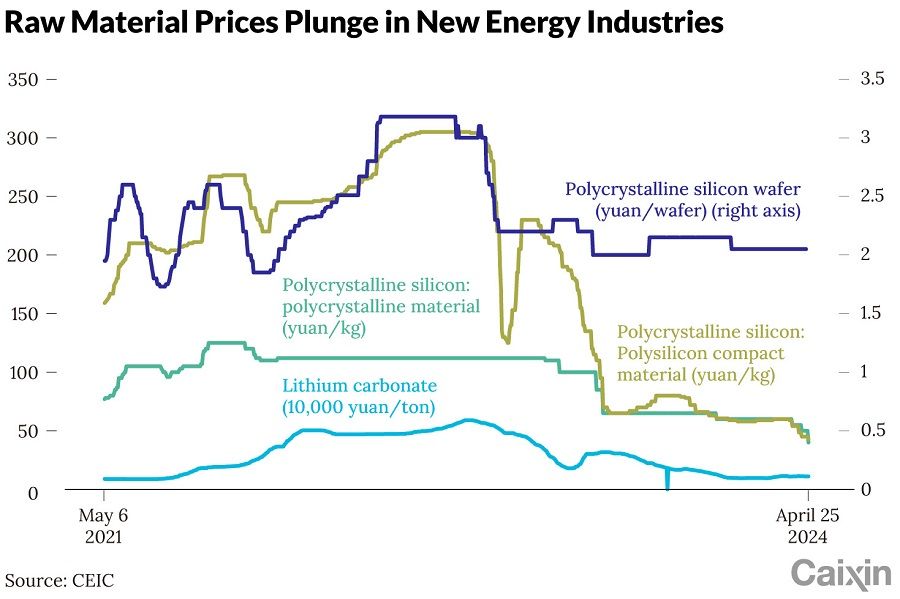

Regardless of the cause, China’s EV industry was plunged into a price war at the beginning of 2023. Except the top three EV makers —Tesla, BYD and Li Auto — most companies did not complete their sales targets for the year. At the beginning of 2024, all three leaders launched a new round of price cuts with even deeper discounts across a wider number of models.

These three aside, Chinese NEV firms generally suffer 10,000 RMB to 30,000 RMB (US$1,409 to US$4,227) in losses for every vehicle sold, according to Wu Songquan, chief specialist at the China Automotive Technology and Research Center.

After domestic sales of NEVs fell some 10% year-on-year to 395,000 units in February, according to data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, the price war began to spread upstream in the industrial chain. The price of lithium carbonate, essential for battery production, plummeted to just 97,000 RMB per ton in February from 510,000 RMB at the start of 2023.

The NEV industry is not alone. The wind power sector, despite achieving record installations in 2023, faces profit margin struggles, with industry leaders not spared. Goldwind Science & Technology Co. Ltd., the largest wind turbine maker in the world, reported a 44% decline in profit last year, while Shanghai Electric Wind Power Group’s net loss nearly tripled.

The ongoing cycle of price wars and resultant financial strain are forcing companies to downsize and streamline operations. This is rumored to have led some firms in the photovoltaic sector to contemplate significant layoffs. The situation is grim in the automotive field as well, with major players like Tesla Inc. announcing global layoffs after a downturn in deliveries.

Dual approach

Amid this business and political landscape, China’s historical approach to tackling overcapacity through supply-side reforms is being tested anew as the country faces current challenges in both emerging and traditional industries.

The past reforms mainly targeted state-owned sectors such as steel and coal, where the government was well motivated to cut capacity and drive consolidation to bail out state-owned enterprises, said Morgan Stanley’s chief China economist Robin Xing.

Today, the industries at risk, including leading battery and NEV enterprises, are predominantly private companies, and the government is more willing to see Chinese enterprises increase their share of the global market, while paying less attention to domestic profitability, said Xing.

Supply-side reform is still necessary, but past experience cannot be simply duplicated with private enterprises, said Zhong Zhengsheng, chief economist at Ping An Securities.

Private enterprises are usually more dependent on market mechanisms and are profit-driven, and it is not easy to reduce capacity by administrative orders. By following trends in energy consumption, quality and standards, private companies can be more effectively encouraged to actively eliminate dated capacity, Zhong suggested.

Analysts also argue that resolving overcapacity is not just about reducing capacity, but also improving the exit mechanisms for manufacturers. In other countries, overcapacity was dealt with through bankruptcies, said Jörg Wuttke, chief representative of BASF China and former president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China.

“China has to find a mechanism for companies to smoothly go bankrupt and exit the market,” Wuttke suggested.

Wang Dan, chief economist at Hang Seng Bank China, has recommended a two-pronged strategy: letting traditional industries such as steel and cement consolidate through bankruptcies, while supporting burgeoning sectors such as green technology with long-term plans and access to international markets.

As short-term domestic demand is difficult to expand rapidly, overseas markets are still an important channel, said Lu from Peking University. In the context of globalisation, obtaining global market share through fair competition is the natural right of Chinese enterprises, Lu said.

It is obviously unfair to claim that China’s competitive advantage is solely subsidy-driven when Western nations are employing parallel tactics. — Robin Xing, Chief China Economist, Morgan Stanley

In the face of restrictive trade practices abroad, China must defend its companies’ rights to compete globally, emphasising fair competition and opposing protectionism, Lu added.

Resurgence of protectionism

As the West criticises China for gaining competitive advantages through industrial policies such as subsidies, it is worth noting the global resurgence of similar strategies, including in the US with initiatives such as the Inflation Reduction Act and chip subsidy bills.

It is obviously unfair to claim that China’s competitive advantage is solely subsidy-driven when Western nations are employing parallel tactics, said Morgan Stanley’s Xing.

In the global race for innovation and competitiveness, supportive industrial policies remain a crucial strategy, evidenced by China’s successful leap in the EV market. This progress was not just policy-driven, but also a testament to the competitive prowess of private enterprises in open market environments, some Chinese analysts have argued.

Looking ahead, scholars are actively exploring ways to refine the scope, mechanisms, and impact of these policies.

Huang Yiping, dean of the National School of Development at Peking University, advocates for a refined approach to industrial policies, suggesting that they should focus more on fostering innovation rather than merely boosting production.

A reorientation of fiscal policies towards human capital investment — enhancing education, healthcare, and social security to integrate migrant workers into urban societies and bolster the welfare of rural populations — is needed, said Zhu Baoliang, chief economist and researcher of the National Information Center.

Lu also stressed that while China should continue to advance its supply capabilities and promote industrial upgrades, urgent macroeconomic policies and structural reforms are needed to correct the supply-demand imbalance by improving household income.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: How Do the West’s Concerns About China’s Overcapacity Stack Up?”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.