How the Chinese learned dance and music before there was YouTube or TikTok

A senior of mine said she was clearing out some old books and asked me to take a look. One wall of the hall was taken up by a shelf stuffed full of books, mostly on society, history and philosophy, which I probably would not use, and I felt apologetic at not being able to help.

Just as I got up to leave, my friend said, "There are some more books, do you want a look?" She turned and brought from her room two black boxes, the kind with metal corners, which gave a sense of age. Two boxes of old books, mostly manuals of dance steps. Some dances I knew, like "Ball-kicking", "Red Silk Ribbon", "Pulling Carrots", "Picking Tea and Catching Butterflies", and "Peacock"; quite a few I never heard of.

My friend was into folk dancing, and these were surely her work materials. Rather, her youth was ensconced in these books.

"You're really not keeping them? That's a pity."

I cannot recall what she said then, but I do remember her inscrutable expression with the corners of her mouth slightly turned up.

A time when one learnt dance steps from books

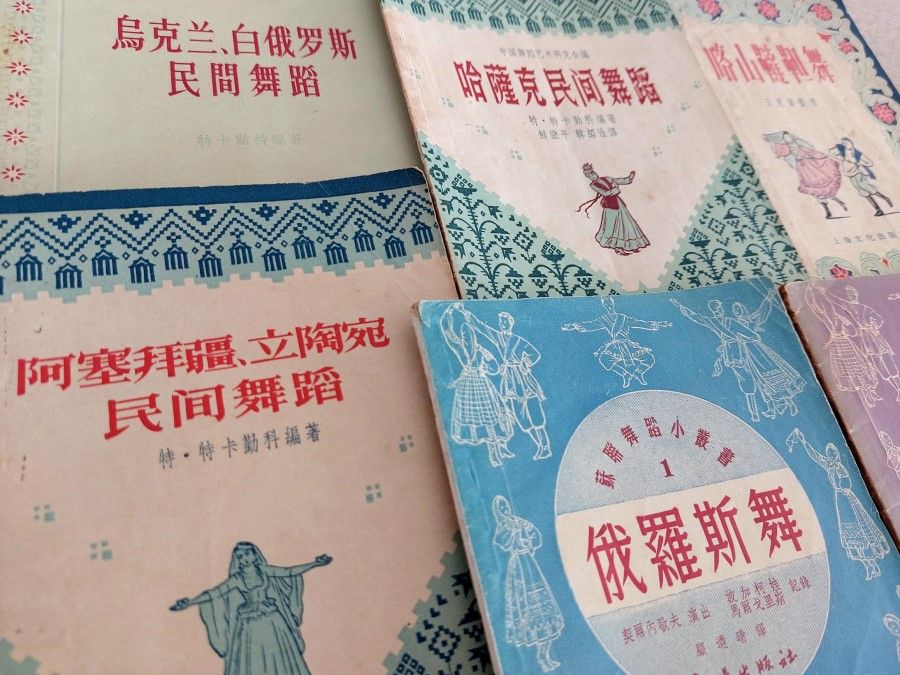

Later, I counted over 100 volumes of China-published dance books from the 1950s to 1970s, the oldest a set of four books on Soviet folk dances published in 1952. There were also quite a few from the late 1950s and early 1960s; one book from 1955 featuring a dance of ten sisters admiring lanterns in Yunnan had a handwritten note on the flyleaf: "Purchased at Shanghai Bookstore."

The newest were some "Cultural Revolution"-type dances from 1974: "Soldiers on the Road"; "Female Civilian Soldiers on the Grasslands"; "Sending Food in Jiangnan" - these were clearly not purchased in any bookstore. Perhaps after the 1970s, there were other ways of teaching dance.

Before video clips became common, besides word of mouth and in-person teaching, the books were probably the only way for people to learn dance on their own.

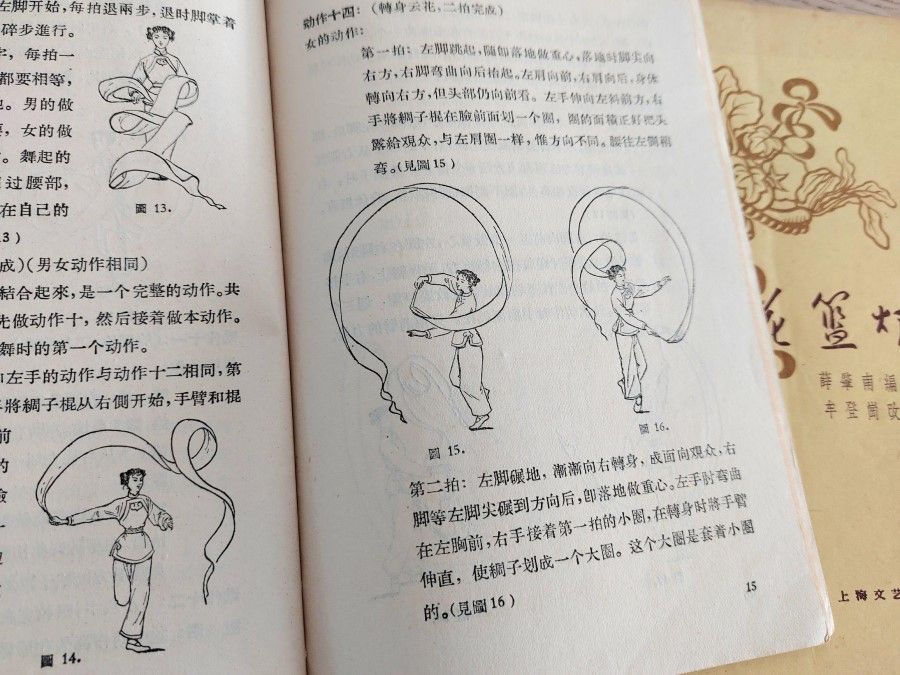

So-called dance books mean those that show dance movements and positions with text and images. Before video clips became common, besides word of mouth and in-person teaching, the books were probably the only way for people to learn dance on their own.

The movements for "Flowers and Youth": "As each step begins, extend and straighten the leg on which your weight rests; place the sole of the other foot on the ground; lift the heel; raise the body and pause for a moment; lower the heel; bend both knees slightly." This comes with two illustrations. And for the hand movements: "Right hand holds the fan, left hand on the waist with a loose fist and thumb against the waist; the first joints of the index finger to the little finger touching the top of the hip."

Imagine how much thought went into turning text and simple illustrations into dance movements.

... they are a collective record of the beliefs, passion and effort of that generation of grassroots dancers, and of the thriving popular culture movement of the time.

From manual to relic

Today, no one would use books to teach dance. What I mean is, the books have a different status; they are a collective record of the beliefs, passion and effort of that generation of grassroots dancers, and of the thriving popular culture movement of the time.

Who taught these dances, who the dancers and audiences were, where they performed - these are all worth looking into. The different dances of various periods also show us the times and eras of a group of people. If the books were split up, each individual volume would have the value of just an old book; it would be a pity not to keep the whole batch.

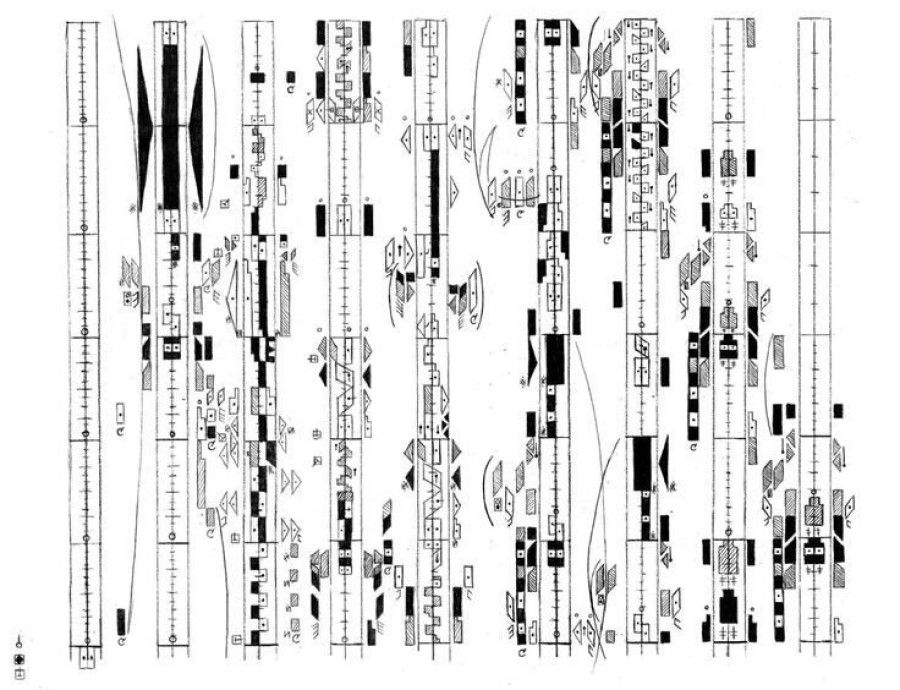

Besides such notations using text and illustrations, I have also seen a type of Western movement notation called Labanotation, which does not use text but abstract symbols to denote the movement of the body in space and the degree of movement.

In 1885, Chinese academic Yang Shoujing was doing research in Japan when he found the score. Through the ambassador to Japan, the score was included in a compilation and published during the reign of the emperor Guangxu, then found its way back to China.

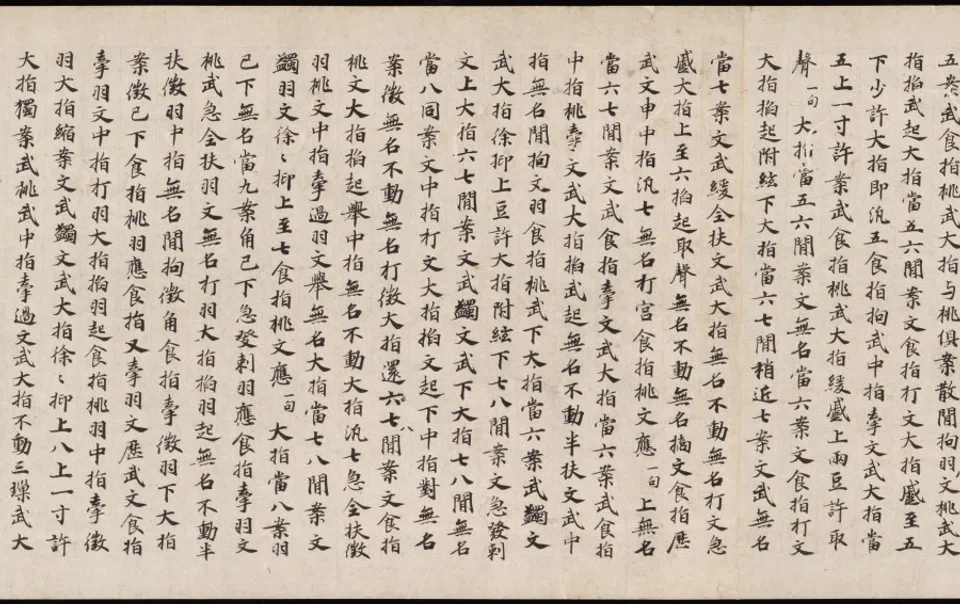

From dance notation, to guqin notation. There are two types of notation for guqin; first a full text, and then a sort of shorthand notation. Guqin player Gong Yi explained that full text notation describes the string and finger positions to produce each note, as well as directions for tempo and dynamics - this can go from one to four lines for a single note.

Story of an old guqin score

So far, the only guqin song I know of with full text notation is Jieshi Diao Youlan (《碣石调·幽兰》known as The Solitary Orchid). The story of how it was found is an interesting one.

The original used to be kept at Jinko-in, a temple in Kyoto, but now it is at the Tokyo National Museum. The score was handwritten by someone in the Tang dynasty, probably during the reign of Wu Zetian. In 1885, Chinese academic Yang Shoujing was doing research in Japan when he found the score. Through the ambassador to Japan, the score was included in a compilation and published during the reign of the emperor Guangxu, then found its way back to China.

Some cultural heritage is just so tied up in the medium that it is carried in - it hangs by a thread and is randomly preserved, otherwise it will completely disappear.

A text score needs to be interpreted before being performed. After the Youlan score went back to China, no guqin player dared to touch it - until 1911, when a guqin master spent three years on the complicated process of completing the performance score and playing the melody. In the 1950s, guqin expert Zha Fuxi found related material and got a few musicians including Wu Jinglue and Guan Pinghu to write the score again. Subsequently, guqin musician Wu Wenguang adjusted the score based on audio recordings.

Some cultural heritage is just so tied up in the medium that it is carried in - it hangs by a thread and is randomly preserved, otherwise it will completely disappear. If Jinko-in did not keep the handwritten score, this old song would not have come back.

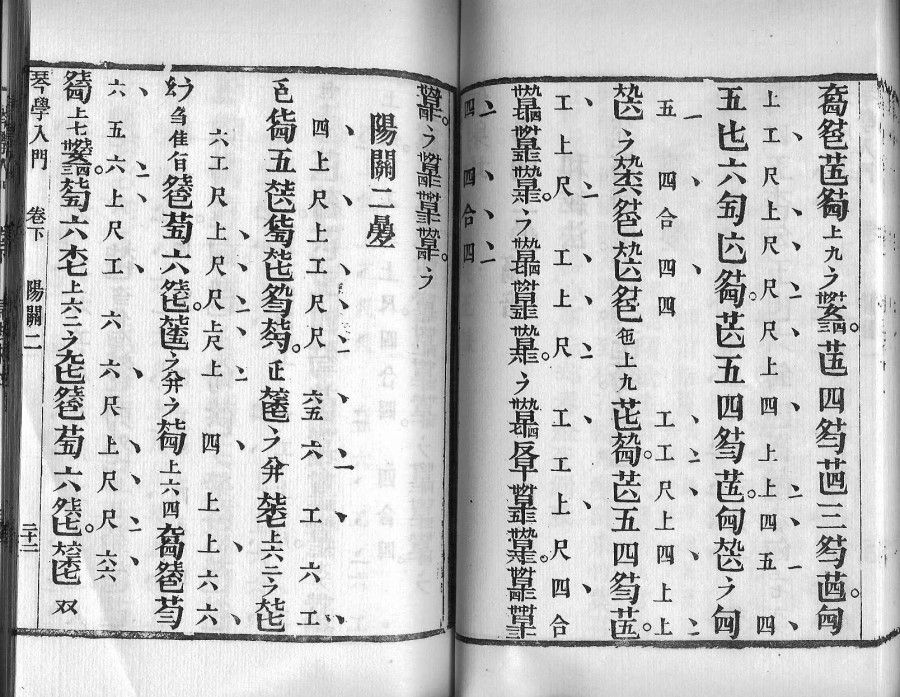

In a book on guqin performance, Gong Yi cites the first line of Youlan, which contains about 80 Chinese characters - with no punctuation or sentences - describing finger placements with estimated positions (in inches) on strings, along with the appropriate movements, such as picking and plucking, and other performance directions, such as to play the note quickly. Perhaps using the mention of various fingers as clues might guide reading, and yet if this long line were to be transcribed as a modern score, there would be only 14 notes.

Text scores are too difficult to read, and so in the late Tang dynasty, there was a change to a "shorthand" score, where various parts of Chinese characters were used as symbols to represent various finger movements and playing styles. While these are much easier to read than full text scores, shorthand scores are still all Greek to those who have never learned the guqin. But while text scores and shorthand scores are difficult to read, it is thanks to them that guqin music has been passed down.