Multilateralism will work only if nations share the same values

Multilateralism is one form of international cooperation, but it is not a requisite. That countries accept multilateralism does not mean that cooperation is a given. Values are the glue in multilateralism; only common values will bring countries to the negotiating table to adjust their interests and lead to results in multilateral cooperation.

Of course, countries will also work together because their national interests go beyond their values, just as the US and Soviet Union came together against fascist Germany. However, conflicting values also meant that after just a few years of cooperation came decades of the Cold War. Values remain the top factor in international cooperation.

Take China for example. Values underpin China's multilateralism ethos; multilateralism is China's method of cooperation in its foreign affairs. China's unique values drive its multilateralism, which it has pursued since October 1949 - however, changing values have also led to China's multilateralism to take various hues.

Values bound China to the multilateralism of the socialist camp, but also tore apart relations between China and the Soviet Union.

Red multilateralism and 'leaning to one side'

First, Mao Zedong instituted the policy of "leaning to one side" (一边倒) - meaning the side of socialism, bringing China into "red multilateralism". This policy was a natural consequence of Mao's preference for socialism. Russia's October Revolution brought Marxism to China with a figurative bang, and it was only natural for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to determinedly join the Soviet-led socialist camp after it came to power. For a time, red multilateralism was the characteristic of New China's foreign policy.

In 1950, China and the Soviet Union signed the "Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance", making them military allies. When the Korean War broke out, Mao's firm choice to support North Korea against the US was also made based on values. This decision alleviated Stalin's doubts about the CCP; after this, Stalin strongly supported China, which truly became a member of the socialist camp.

However, Mao did not agree with Nikita Khrushchev's idea of a socialist "family" with tight economic integration, and decided that China would not join the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon). Independent autonomy and self-reliance were the main thrusts of Mao's pursuits in China's economic development. But doctrinal divergences arose between Mao and Krushchev on issues such as de-Stalinisation reforms and China-Soviet relations fell through, leading to armed conflict on the China-Soviet border. Values bound China to the multilateralism of the socialist camp, but also tore apart relations between China and the Soviet Union.

Second, the market economy as advocated by Deng Xiaoping has bound China with the global economy. China joining the market economy was a revolution in its mindset, because the classical Marxist writers and Stalin's socialist model rejected the market economy, while the capitalist experience showed that the organic integration of the private sector with the market economy is a clear characteristic of the capitalist economy.

Deng separated the market economy from the capitalist economy and transplanted it into the socialist economy. China's market economy brought its economy into the wave of globalisation while awakening China's enormous potential, allowing it to grow into the world's second largest economy. China has stunned the world and proven the great advantages of the market economy.

'Multilateralism with Chinese characteristics'

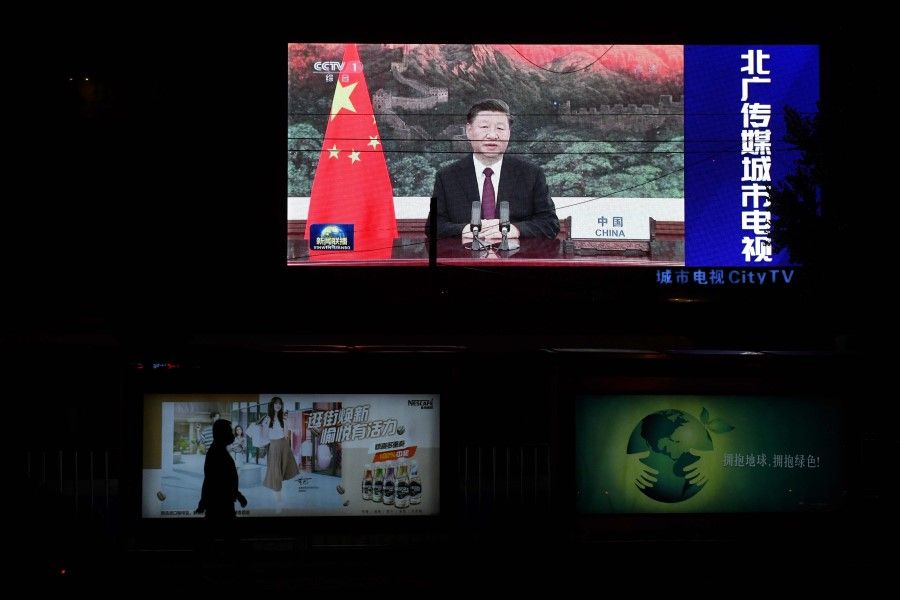

Third, the new era of Xi Jinping has injected the "China solution" into multilateralism, creating a form of "multilateralism with Chinese characteristics", a red multilateralism for the new era that aims to build "a community with a shared future for mankind", and eventually bring about communism.

The differences in values between China and the US means they cannot engage in multilateral cooperation under the BRI framework - values have become an obstacle to China-US multilateral cooperation.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a classic example of multilateralism with Chinese characteristics. The basic principles include market principles - recognising the role of the market and the central position played by enterprises, while allowing the government to perform an appropriate role; that is, it draws on the capacities and functions of both the market economy as well as the government. This is the China model, of which the BRI is an extension outside of China.

But the West sees the BRI as a geopolitical tool for China. In December 2019, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in the US released a report saying that the BRI is not a win-win as Beijing says. US officials, academics, experts, and journalists seem to all feel that the BRI is a strategic chip for China to benefit from other countries, and China is using the debt trap to challenge the sovereignty of other countries and develop infrastructure for both military and civilian use, and that it is setting up a network of military facilities in the Indo-Pacific and Asia-Pacific regions.

The different values of East and West have led to very different views of the BRI, which sets up the US and other major Western countries to resist the BRI. The differences in values between China and the US means they cannot engage in multilateral cooperation under the BRI framework - values have become an obstacle to China-US multilateral cooperation.

China has sought to change the Western concept of human rights with its own understanding, which the West definitely does not accept.

Different values will get in multilateralism's way

It has been proven that multilateralism may not lead to cooperation between countries. The WTO is multilateral, but the Doha talks in 2001 did not seem to show much results, because countries had doubts about whether free trade would benefit them. The concept of free trade may not be deep-rooted, and trade protectionism is hard to get rid of. Free trade is just politically-correct talk by politicians.

The UN is also multilateral, but China and the West are constantly bickering over human rights without leading to cooperation, or even a common understanding of human rights. China has sought to change the Western concept of human rights with its own understanding, which the West definitely does not accept. The multilateralism of the UN has provided a platform for the tussle between opposing views of human rights between China and the West.

China and Australia are both members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), but no one is under the illusion that China-Australia tensions would be eased within the RCEP. And can the RCEP boost relations between China, Japan, and Korea? The animosity of the Chinese against Japan is expected to last for a while yet, and the Japanese do not believe that the RCEP will strengthen China-Japan relations.

And right now it looks unimaginable that China will accept the clauses rejecting partisan leadership, unless the CPTPP makes an exception for China.

Fourth, it will be difficult for China to join in multilateral cooperation efforts with Western values. China's current top leader has said that China is actively considering joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which is the abridged version of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) designed by the US with a clear nod to values.

For China, the CPTPP retains the clauses touching on sensitive issues, such as competitive neutrality in relation to state-owned enterprises, subsidies, and technology transfer. It is no coincidence that these clauses are in line with the US government asking China to implement structural reforms in the China-US trade war; it reflects that those who came up with the TPP saw the fundamental differences between a government-led economy and the Western market economy.

The labour clauses in the CPTPP reject partisan leadership, but advocate core labour standards and the requisite "freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining", which explains why China only ratified 26 out of 177 conventions in the International Labour Organization's (ILO) international labour standards. Most importantly, China has not ratified international agreements that are representative of values - the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize Convention, the Forced Labour Convention, and the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention.

If China formally asks to join the CPTPP, it will be obliged to accept the rules; there is no chance of China negotiating the rules with the other members because China is not one of the original signatories. And right now it looks unimaginable that China will accept the clauses rejecting partisan leadership, unless the CPTPP makes an exception for China.

Going by China's values, the West's criticism of China means that it wants to contain China, but along China's route to multilateralism, managing conflicts in values with the West is a real question.

West is unlikely to budge

Fifth, in recent years, the West has discussed and criticised multilateralism with China characteristics, which - going by Western values - is a tool for China to benefit from as a big country.

On 24 November, The New York Times published a commentary written by its bureau chiefs in Beijing and Shanghai, discussing "globalisation with Communist characteristics". The piece made these points: "The Chinese government promotes the country's openness to the world, even as it adopts increasingly aggressive and at times punitive policies that force countries to play by its rules"; "China wants to become less dependent on the world for its own needs, while making the world as dependent as possible on China"; "[China] wants to follow international rules and norms when it is in its interest, and disregard rules and norms when the circumstances suit it".

Going by China's values, the West's criticism of China means that it wants to contain China, but along China's route to multilateralism, managing conflicts in values with the West is a real question. Without values as a glue, it will be difficult to bring about multilateralism; at least, cooperation of any depth with the West will be difficult.

Of course, the world is not just the US and Europe - countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America can also be China's partners. But without the US and Europe, would China's economic and technological development be better or worse?

Related: Why China is rejoicing over the RCEP | Growing China's soft power: Free debate and creative thinking are key | New battleground for China-US competition: International organisations | China has entered the 'gilded cage' of RCEP and is considering the CPTPP. What's next? | RCEP: The start of a new 'China-centric' order? | Is China attempting to change the world order? | America and Europe are coming together against China, but will it work?