[Photo story] A history of Western illustrations insulting the Chinese

(All images courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao)

For over half a century, Western countries have used images to vilify and humiliate the Chinese. These images tend to peak especially when there is conflict between both sides. Even after the conflict, the stereotypes created will stick in the minds of many Westerners to form an unconscious idea of the Chinese, a preconceived notion that guides many Westerners in explaining the behaviour of the Chinese as individuals and as a nation.

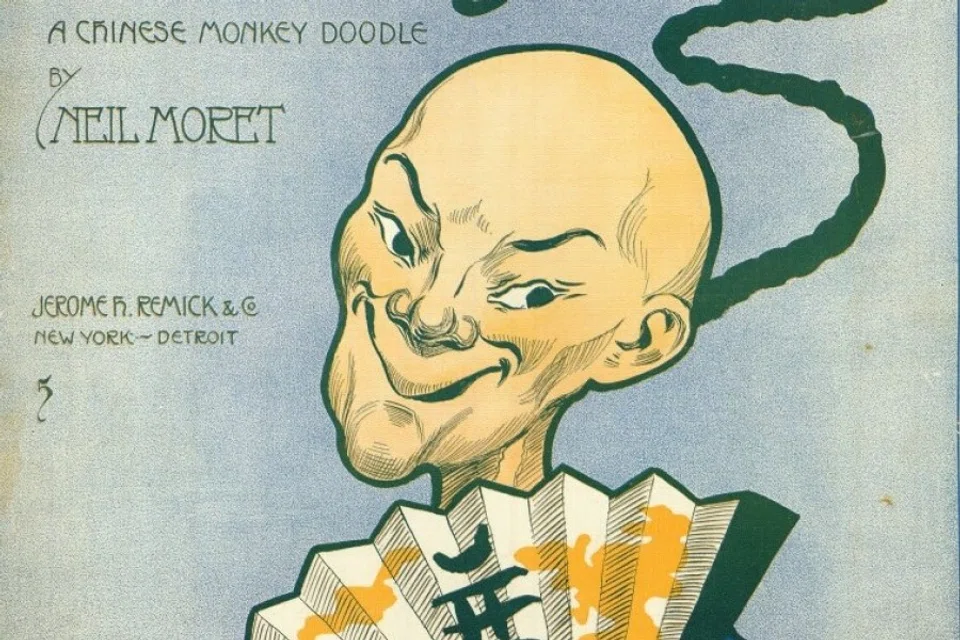

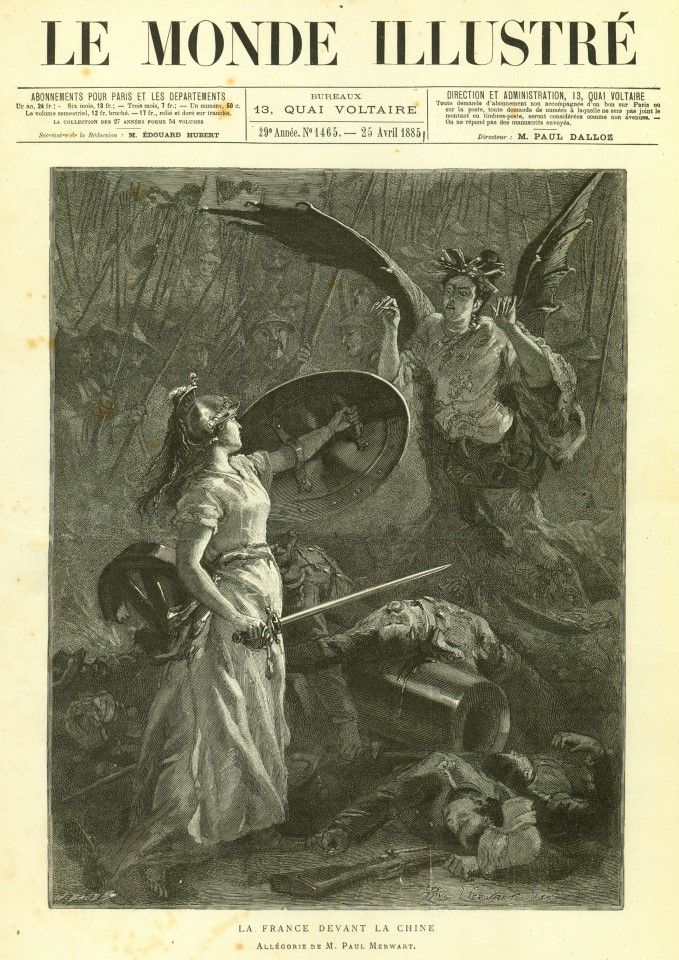

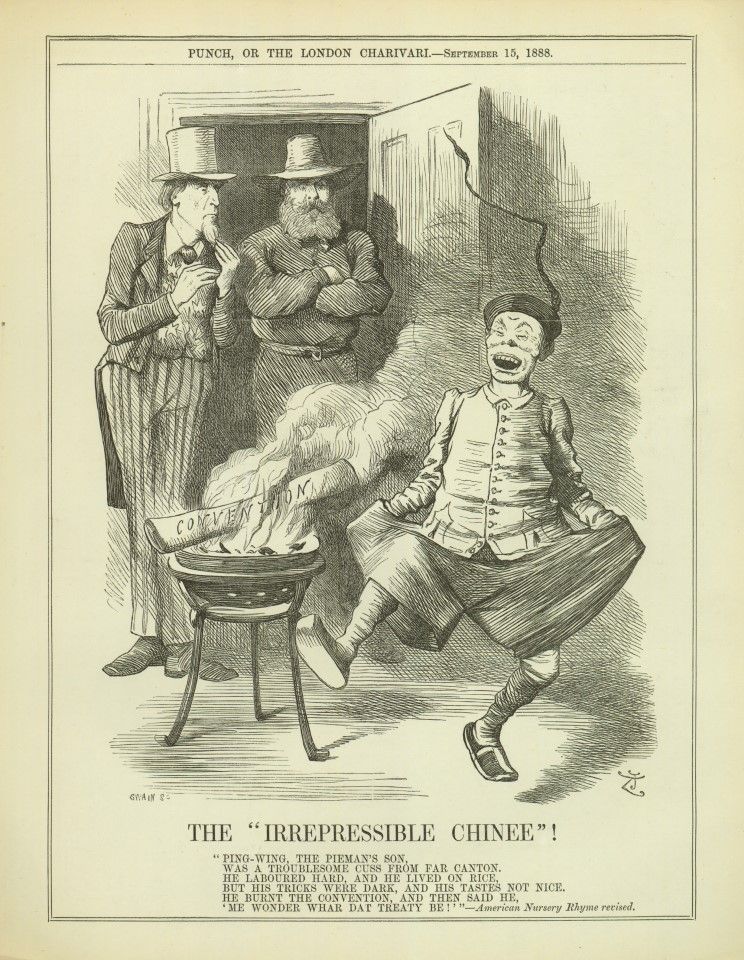

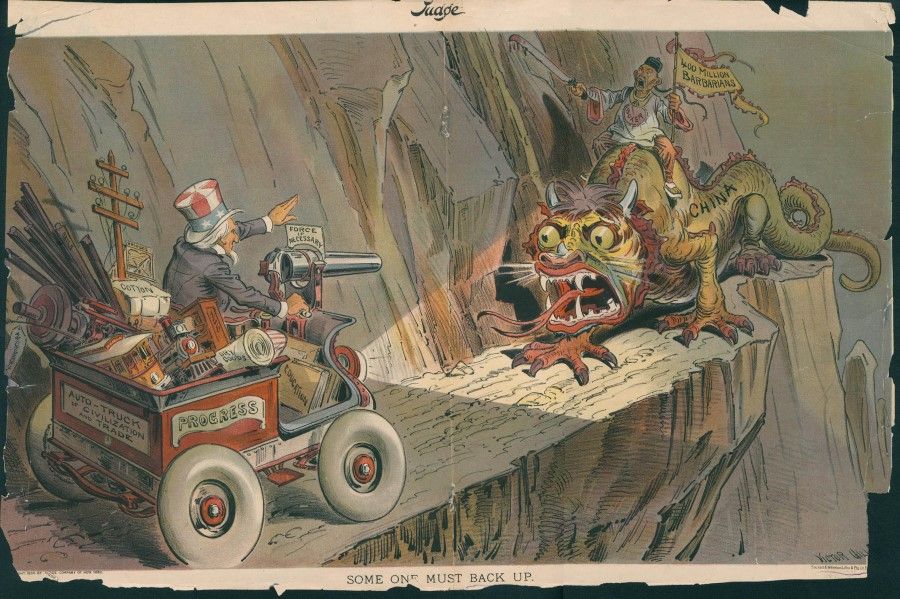

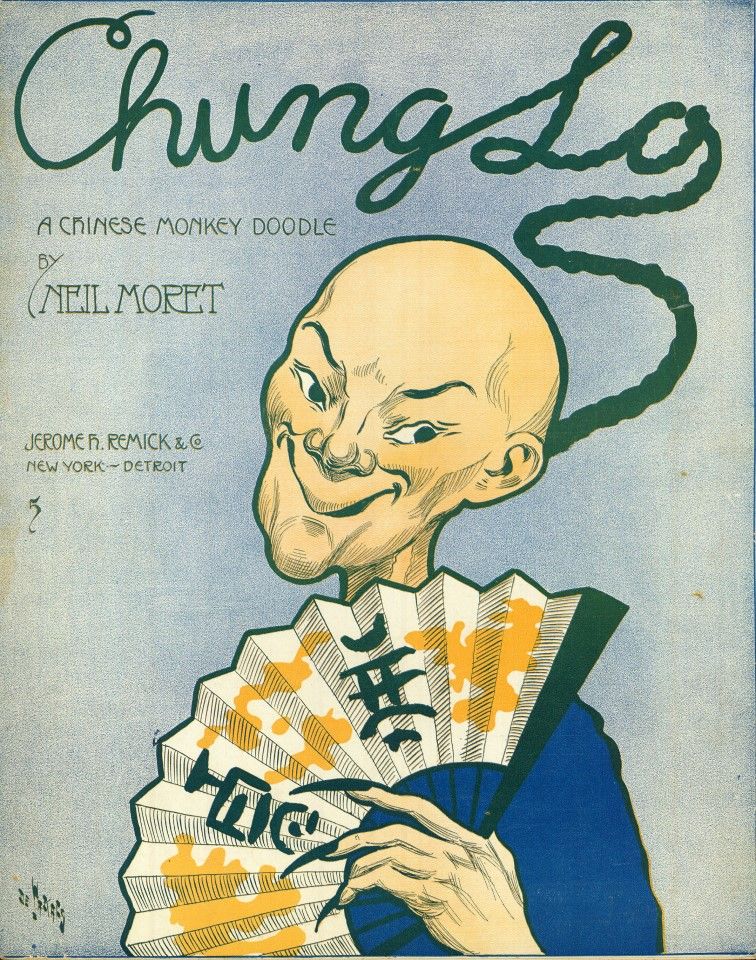

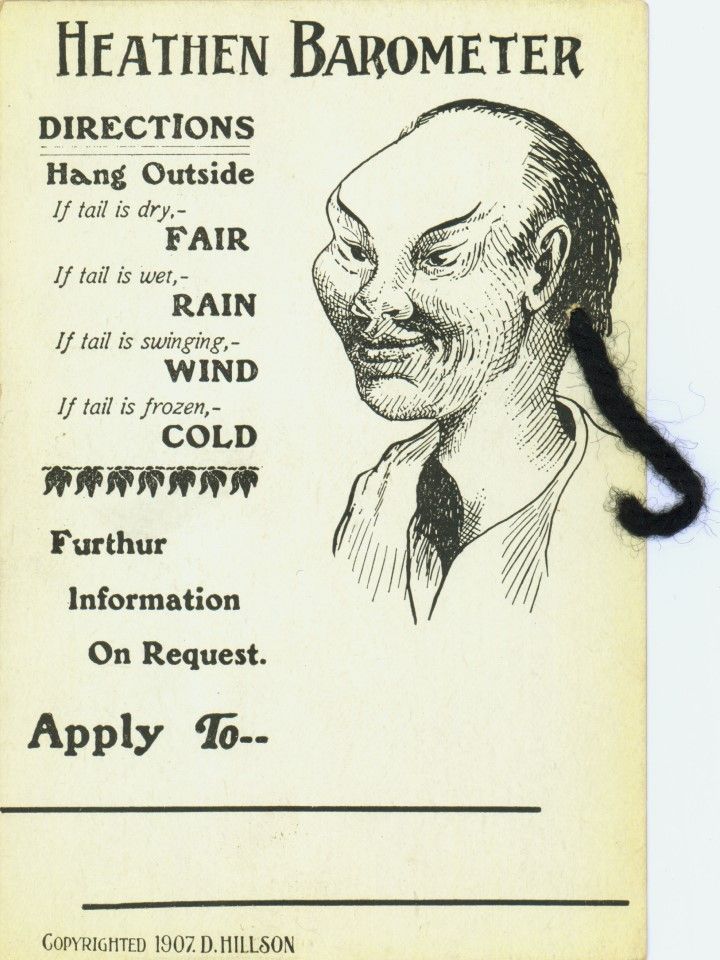

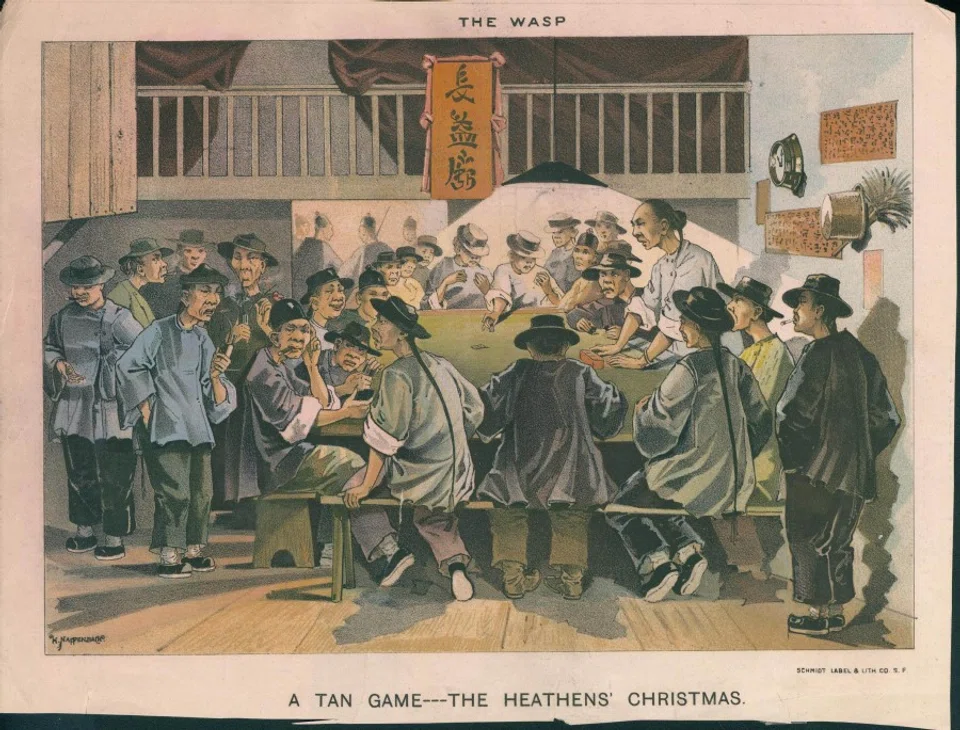

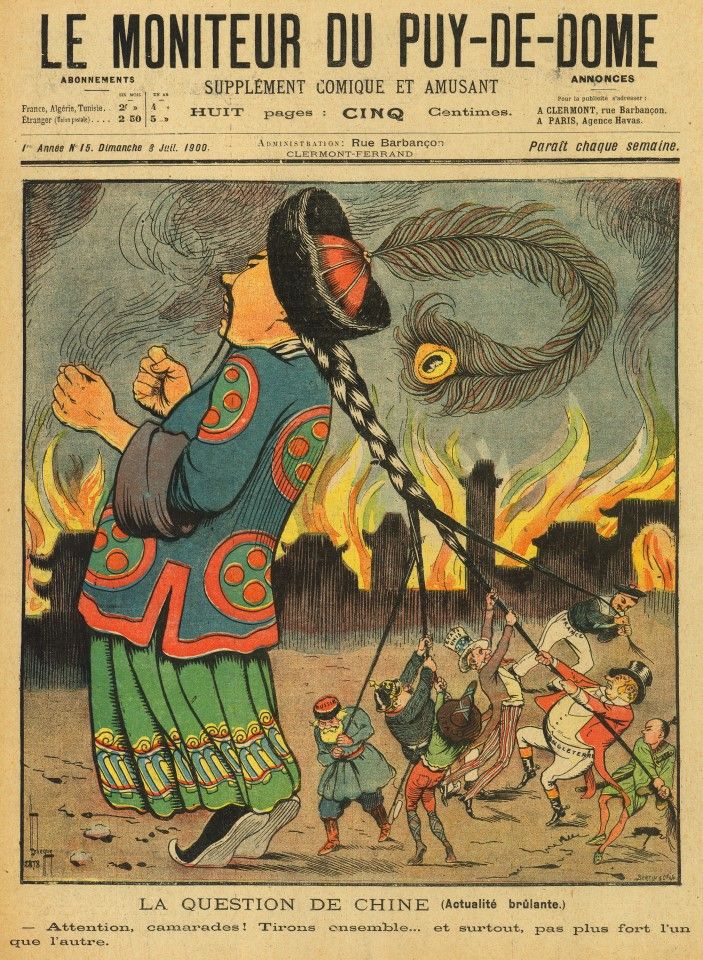

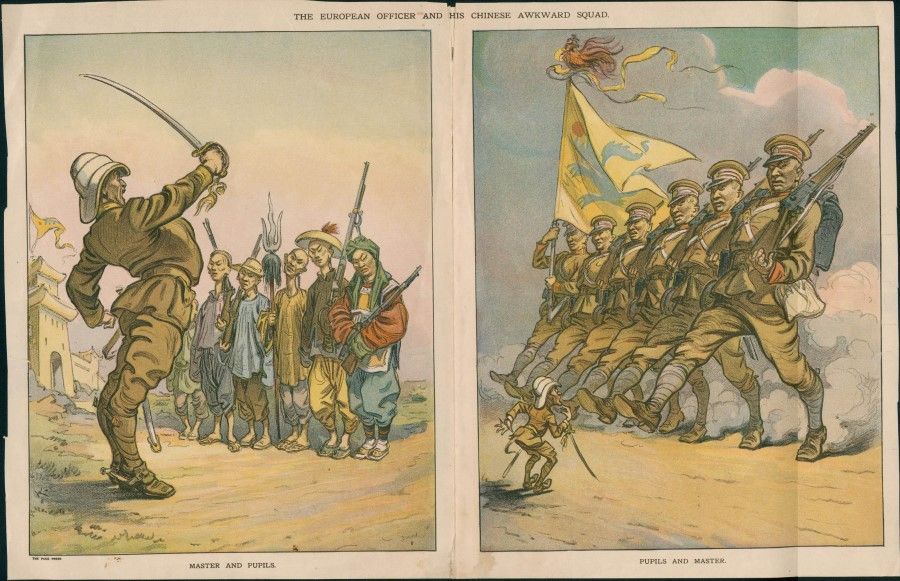

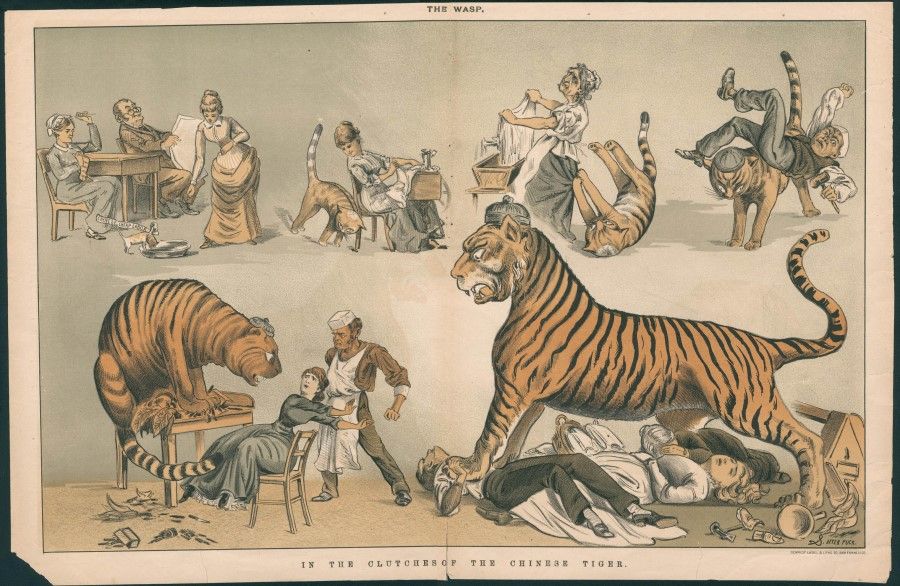

Making fun of queues and small eyes

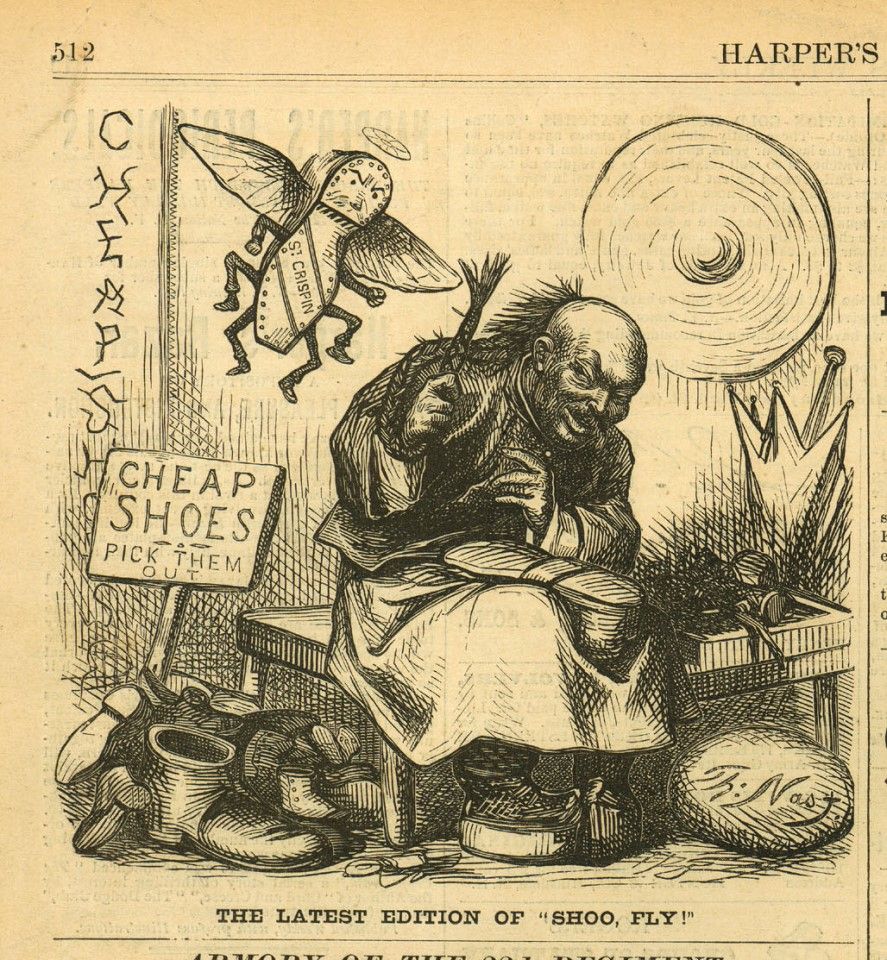

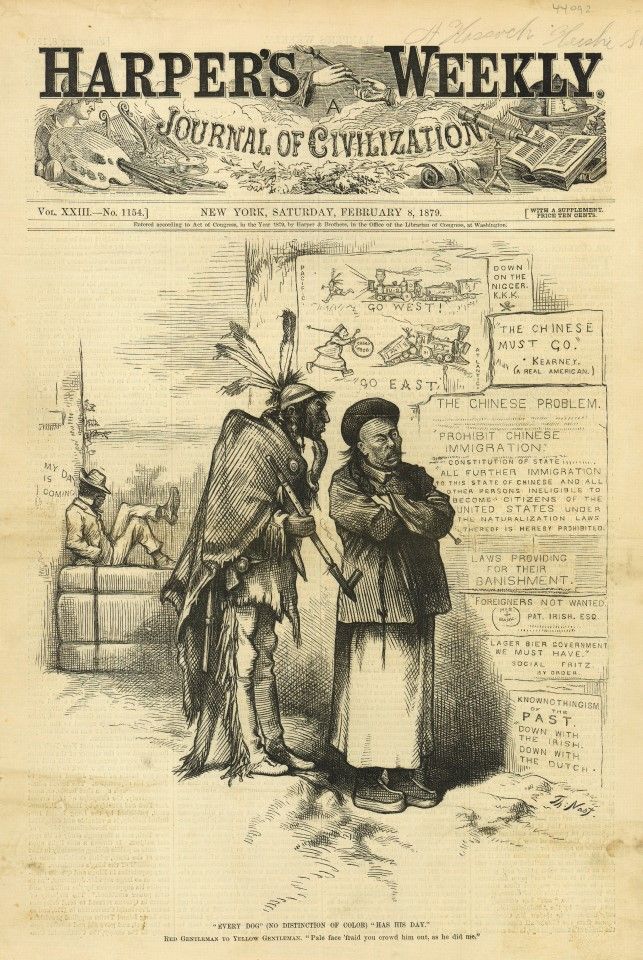

In the mid-19th century, as the West started to include China in its growing colonial empire and conflicts over sovereignty and interests cropped up, images started appearing in the West that caricatured the Chinese. This was not difficult; the Chinese rulers at the time were Tatars from Manchuria, where the men shaved the front half of their heads and had long hair braided into queues behind - not only that, all the other men in the country were also required to do the same. Even though Western adult males now also sport ponytails as a fashionable artistic image, the queues on the Chinese men of a century ago seemed strange and laughable. Also, given that the eyes of the Chinese are generally narrower and longer than those of Westerners, the queues and slit eyes were often the subject of unrestrained mockery by Western illustrators. And with the dragon being the symbol of the Chinese, China was also often drawn as an ugly dragon. Perhaps the unconscious rationale behind vilifying China and the Chinese was to justify Western military colonisation: after all, "backward, barbaric" China needed to be figuratively baptised by advanced Western civilisation.

In 1882, there was a wave of sinophobia in the US, and in a clear act of racism, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act to restrict Chinese from entering the US and bar them from getting US citizenship. This had nothing to do with the situation in China, or even China-US relations, but was borne out of US domestic politics.

In 1869, after the Pacific Railway was completed, the many Chinese workers who were recruited to build it lost their jobs, and so they flocked to the large cities on the US east and west coasts, seeking new opportunities.

These industrious Chinese labourers worked day and night, scrimping and saving to give the next generation a better education so they could get out of the poverty experienced by the first-generation immigrants. Because the Chinese were willing to do more work for less pay, they were popular among capitalist employers, but they also took jobs away from many low-level white workers, and there were incidents of violence against Chinese in some major cities.

The Chinese did nothing wrong, except for working too hard, and in the end the angry white workers got Congress to openly censure the Chinese and pass the Chinese Exclusion Act. During this time, US newspapers published many images insulting the Chinese, with their queues, small eyes, looks, and even their accent when speaking English all becoming targets of mockery. The Chinese were "freaks", "cheap labour", "pagans", "job stealers", "dirty". Indeed, the Chinese did have some obvious shortcomings, most of which were due to poverty, but which were often described as inherent flaws of the community.

Seeds of China's victim complex sown

In 1900, the Boxer Rebellion broke out in China against the West, and the world powers suppressed it through military means, gaining large reparations from China and stationing their military in the Chinese capital of Beijing. This led to a thriving sex industry in Beijing, and many Western soldiers took photographs of their exploits in Beijing's brothels as mementos in their private collection, so that they could brag to their friends back home.

Amid this humiliation and bullying, the Chinese learned one fact: out of all the flaws they were accused of, only one thing was true, which was that their country was so weak that being manipulated was all it was good for. To reverse the bullying, China had to grow strong, because a weak country would not even be capable of gathering and showing evidence to clarify any truths it might hold.

During World War II, the US fought with China against the Axis powers. This changed the US's attitude towards China, and it repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act. After the war, with greater global awareness of democracy and human rights, the blatantly racist vilification of China gradually faded away, albeit still with the occasional negative stereotypes of Chinese in popular culture such as movies, TV shows, and books.

Even today, in the face of strong competition from China, there is a sense of deja vu in the rhetoric of Western countries, including "cheap labour", "unfair competition", "stealing jobs", and "stealing technology". There is a deep-seated familiarity and force of habit about this narrative; it comes out readily, so much so that one does not need to think about how China could steal advanced technology from the US, which the US did not even develop.

Related: Anti-Asian hate crimes: What makes an American? | Mulan: The people-pleaser that ended up offending all? | Americans should not oversimplify China into a few sensitive issues | [Photo story] When Chinese are not welcome | Where multiple 'gods' coexist: Countering the racism complex in Western diplomacy | From 'yellow peril' to sinophobia | Who should apologise for the term 'sick man of Asia'?