Taiwan: Why China-US relations are a zero-sum game

Chinese academic Ni Lexiong says that so long as a country's territorial sovereignty is in conflict with the hegemonic system governing the world, the likelihood of escalation to war is there. That is why despite any of the posturing at the recent Alaska talks, the situation between China and the US remains deadlocked in a zero-sum game.

Are China-US relations falling off a precipice, or slowly rolling down a slope?

Historically, as two countries move towards the spectre of war, there will be talks that appear to be an effort to salvage relations. Before World War II, frequent UK-Germany, USSR-Germany, Poland-Germany, US-Japan talks were held amid deteriorating relations. And historically, at least half of such talks were a waste of time, like vegetation temporarily halting the fall of a rock: there may be a rebound, but the rock will ultimately continue its descent into the abyss. Of course, vegetation can also slow down a rock's path along a slope. So, is the Alaska meeting between China and the US vegetation along a slope or a cliff?

Both sides lay the ground

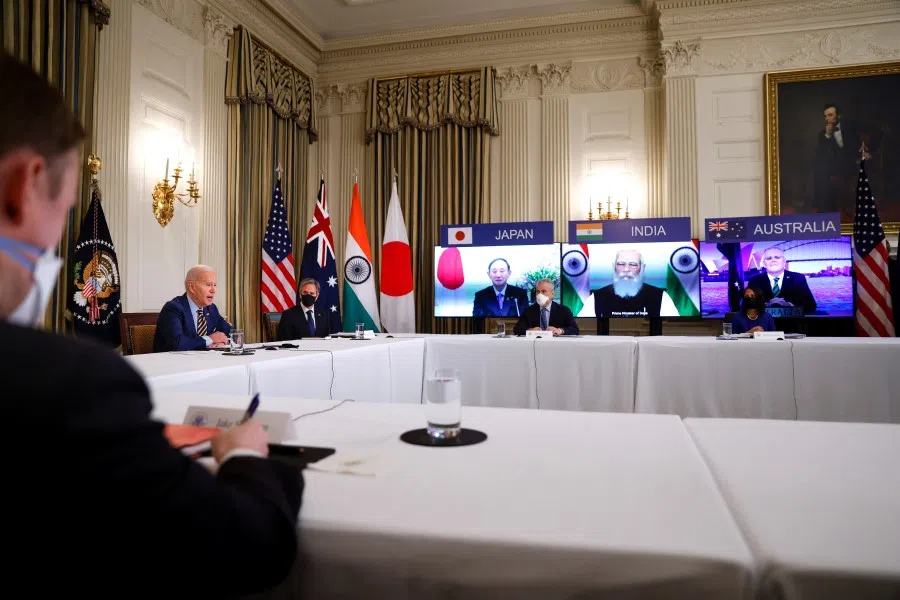

Judging from the words and actions of the US and China prior to the Alaska meeting, both had wanted to bolster their respective strengths in order to carry more weight during the talks. The US seemed to have more chips, and its many actions were overwhelming. On 12 March, the Quad countries of the US, Japan, India, and Australia - also referred to in some quarters as the "Asian mini-NATO" - held a virtual leaders' summit, where they agreed on vaccine cooperation and started to establish a supply chain for rare earths, a key strategic asset. Such cooperation does carry other meanings.

On 16 March, the US and Japan held a "2+2" meeting of foreign and defence ministers, following which they issued a joint statement pointing fingers at China, with Japan throwing its lot in with the US. And on 17 March, the US government announced financial sanctions on 14 Chinese officials. With US President Joe Biden's efforts at cooperation showing clear results, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken strode proudly into the Alaska talks.

China also flexed its muscles. In late February, China's Maritime Safety Administration in Guangzhou announced that month-long military exercises would be held in the South China Sea west of the Leizhou Peninsula, calling it an air-to-sea offence exercise. Obviously, talks held in such an atmosphere would not be optimistic, and even if there was some compromise in secondary issues, it would not change the overall deteriorating situation.

Generally, talks held under such circumstances would only involve both sides reiterating their stance on issues of principle and core interests, without any compromise. Both political parties in the US agree on total containment of China, as shown by the almost unanimous passing of a host of relevant bills in Congress.

Non-hegemonic countries see territory and sovereignty as core interests; for hegemonic countries, their core interests also include upholding the hegemonic system, even if their territory and sovereignty are usually not directly impacted...

Grandstanding belies zero-sum attitude

If there was any meaning left to talks where both sides feel that the situation is hopeless, it would be getting a feel of each other face to face, to test the other side's strength and resolve, in order to calibrate its response and come up with stronger and more targeted policies and strategies, which would lead to more intense conflicts in the future. Behind all the appearances, the conflict between China and the US is fundamentally due to a mutually exclusive, zero-sum relationship.

Why is the China-US relationship a zero-sum game? The answer lies in history, especially in war history. Indeed, history is a mirror that reflects a power's rise and fall. Usually, a country chooses war because its core interests are directly impacted. Non-hegemonic countries see territory and sovereignty as core interests; for hegemonic countries, their core interests also include upholding the hegemonic system, even if their territory and sovereignty are usually not directly impacted - otherwise, they would not be hegemonic.

During World War II, Britain and France did not declare war on Germany because their own territorial sovereignty was violated. When Poland was invaded by Germany, the Versailles system and the Locarno Treaties established by Britain and France were violated, as was their alliance with Poland, as well as their credibility and dignity. Britain and France had no choice but to grit their teeth and declare war on Germany, otherwise they would no longer be able to show their face on the international stage.

It has to be pointed out that perhaps Germany felt that since it was taking back the territory it lost in World War, and it had managed to have its way with the British and French leaders signing the Munich Agreement, Britain and France would show a degree of tolerance. But it did not realise that keeping Poland whole was a part of the Versailles system, and part of the core interests of Britain and France.

Similarly, the US sent troops to North Korea, Taiwan, Indochina, the Middle East not to fight to protect its own territory and sovereignty, but because the post-World War II hegemonic system and the duty, credibility, dignity (or "face"), status, and agreements that came with it were seriously challenged.

When the Second Punic War (218-201 BC) broke out, Rome declared war on Carthage not because its own sovereignty and territory were threatened, but because Carthage invaded Rome's strategically significant but non-allied neighbour Saguntum, and crossed the Ebro river, which Rome had marked as a "red line", rocking Rome's hegemonic framework. This also explains why almost all hegemonic countries have a record of sending troops everywhere. In modern times, this is especially true of the US, which pokes its figurative nose everywhere.

One conclusion can be reached: regional or global hegemonic frameworks are the core interests of those who establish them, and it is a state of affairs that even the hegemonic countries cannot undo. Hence, hegemonic countries see the hegemonic systems that they establish as core interests, and are willing to go to war for them. Of course, from another perspective, it is the duty of hegemonic countries to uphold the hegemonic system, and it is also a heavy financial burden. This is why former US President Donald Trump wanted to collect "protection money", and why its allies were unhappy.

The main dilemma

The reason why China-US relations do not look promising is because the core interests of the two countries are in conflict over the Taiwan issue, resulting in an irreconcilable zero-sum relationship. That is, China and the US are clashing on issues concerning national unity, territorial integrity, and the hegemonic system.

One country raises the flag of justice, holding sacred a state's territorial sovereignty. Another country holds up its own flag of justice, holding sacred its commitment to peace to all mankind.

Take the example of Anglo-German relations prior to the Second World War. The fast-rising Germany thought that it had consolidated its power and wanted to regain a territory that it had lost - the Polish Corridor. The Germans greatly supported German reunification and this approach was also in line with national justice.

Poland refused to make any concessions because of the international laws behind the Versailles System; it believed that when the defeated Germans ceded the Polish Corridor to it, this was recognised by international law and also a part of the postwar peace system. However, Germany's demand for reunification clashed with the Versailles System established by Britain and the other victor countries of World War I. As the core interests of Britain and Germany were in conflict with each other and nobody wanted to compromise, war broke out between them and their allies in the end.

Countless wars have revealed some sort of a historical pattern: once a country's territorial sovereignty is in conflict with the hegemonic system, it is only a matter of time before war breaks out. This is because both parties are locked in an irreconcilable zero-sum relationship.

One country raises the flag of justice, holding sacred a state's territorial sovereignty. Another country holds up its own flag of justice, holding sacred its commitment to peace to all mankind. Both sides seem to be within reason and taking actions that are perfectly justifiable on the grounds of morality and values. The crux of China-US relations lies in the Taiwan issue which is precisely an irreconcilable dilemma between territorial integrity and the hegemonic system. The zero-sum nature of this dilemma has made pessimists think that war would break out between China and the US sooner or later, which does not seem that exaggerated a view at all.

It is because of the Gordian knot that is the Taiwan issue that has caused China-US relations to fundamentally be held hostage by hostile and irreconcilable differences.

Imagine this: if the Taiwan issue did not exist between China and the US, then the nature of the trade war, intellectual property dispute, and tariff war would be economic, just like what the US is facing with its allies. Ultimately, it is just a matter of who has more money or less money. Differences in ideological and political systems are no big deal as well. Just look at Saudi Arabia and Qatar - they are monarchies but they get along with the US and other Western democratic countries. As for the human rights issue, both parties have come to a compromise in the past before and it is hardly a conflict of core interest.

It is because of the Gordian knot that is the Taiwan issue that has caused China-US relations to fundamentally be held hostage by hostile and irreconcilable differences. All other secondary differences have also turned hostile in nature because of the Taiwan issue, and become bargaining chips for confrontation. For example, the complete ban on China in the science and technology field is imposed with the view that war would break out sooner or later, as well as a need to maintain absolute superiority of military technology and high-tech weaponry over China in the long term. Former US President Donald Trump has already implemented these policies during his term in office, and the incumbent Joe Biden administration is left with no choice but to continue with them.

To have a clearer picture, we have to study China-US relations by making comparisons in a historical time frame. Looking at it over time, the Hawaii talks concluded in June last year and the most recent Alaska talks are merely ripples carried along by the rapids. Be it from the perspective of history, reality, or logical deduction, we have to be aware of the dangers of an uncompromising attitude when territorial sovereignty is in conflict with the hegemonic system. Even if it is not yet a historical pattern, as long as half of the wars in history can be explained, that would be enough to warn the people that it should not be taken lightly. Those views that say China-US contradictions can be resolved by seeking common ground while setting aside differences would ultimately be disproved under the scrutinising eye of history.

Core interests can cancel out non-core interests, but not the other way around.

The common interests of China and the US are not their core interests. Which of the shared goals - tackling global warming and climate change, maintaining nuclear non-proliferation, and fighting the Covid-19 pandemic, among others - can compare to the loss of state territory and the collapse of the hegemonic system? Core interests can cancel out non-core interests, but not the other way around. So far, the US has sought to decouple from China in areas such as academic exchange, further studies, travel visas, company listings on stock markets, science and technology exchanges, and so on, which are shared interests with mutual benefits but non-core interests. These are meant to wield a deadly blow to the enemy. The extent of the US's decoupling actions shows just how relentless a country's core interests can be in wiping out its non-core interests.

The Alaska meeting will not change the nature of China-US conflict and neither will it stop China-US relations from worsening. The US is systematically planning to comprehensively contain China in the fields of diplomacy, economy, science and technology, strategic resources, education, culture, ideology, military, and others to ensure its absolute advantage over China in middle- and long-distance races. Trump and Biden have just made a hurried start. What the world is about to witness is two major alliances led by the US and China, and countries around the globe battling against each other. That would be far more nerve-wracking than what happened during the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States periods, and certainly much more treacherous as well.

![[Vox pop] Chinese parenting: Tough love or just tough?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/b95bd53631df26290df995775a40e36709bf8dc8e3759460276abd5c426b20b6)