Why did the Taiwanese support China's A4 revolution?

Taiwanese academic Ho Ming-sho asserts that Taiwan's show of solidarity with protestors in China's A4 revolution is better understood under the lens of the history of the island's pursuit of its own identity. He explains why Taiwan's civil-society actors chose to react to the protests on universal values, rather than national sentiment.

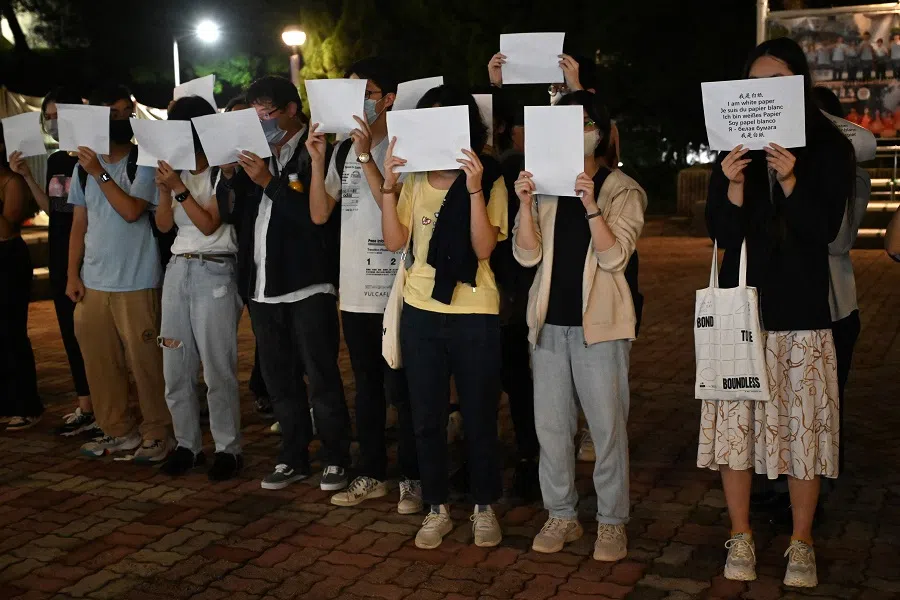

China's anti-lockdown campaigns at the end of November 2022, known as the A4 revolution, amounted to the largest incident of anti-government protests since the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident. Chinese protesters were fed up with the draconian regime of endless PCR tests, forcible quarantines, and arbitrary lockdowns that were in place for nearly three years.

The flare-up of the A4 revolution found rejoinders abroad, as Chinese overseas students initiated their spontaneous actions across university campuses. The sprouting of political dissent shattered the stereotypical image of "little pinks" (ultra-nationalistic youth) who earned their notoriety by harassing Hong Kong and Uighur campaigners. Liberalism and pro-democracy sympathy existed among Chinese overseas students except that they were disinclined to reveal these "politically incorrect" ideas until then.

Taiwanese standing up for human rights

Taiwan also witnessed several rallies for China's A4 revolution. There was a gathering by NGOs in Taipei's Liberty Square, and students from National Taiwan University (Taipei) and National Cheng Kung University (Tainan) also held their campus actions. Different from similar incidents elsewhere in the world, Taiwan's events were not initiated by mainland Chinese students, partly because its number has declined from 42,000 in 2016 to merely 4,000 in 2021, due to Beijing's policy to discourage students from studying in Taiwan.

Common in Taiwan's A4 revolution events was the universal value of human rights, and many participants actually rejected the idea that Taiwanese belonged to the Chinese nation.

Probably because of fewer Chinese participants, these events proceeded less as a commemoration of Urumqi fire victims, which powerfully symbolised unjustified indignities of Chinese people at the anti-Covid measures, but more as a solidarity gesture to those courageous protestors in the mainland. Common in Taiwan's A4 revolution events was the universal value of human rights, and many participants actually rejected the idea that Taiwanese belonged to the Chinese nation.

Lee Ming-che, who was imprisoned for five years in China because of his connections with human rights activists in the mainland, was emphatic in his speech at the rally in Taipei's Liberty Square: "We do not support China's A4 revolution from the perspective of 'global Chinese'." Lee claimed that anyone who believed in human rights was qualified to support the Chinese in opposing their government.

In addition to these civil-society actions, politicians, both in government and in opposition were united in their sympathy for China's A4 revolution - a rarity in the partisanship-rift political landscape in Taiwan. Conspicuously silent was of course the vocally pro-Beijing Terry Gou, Foxconn's founder, whose Henan subsidiary operated with an inhuman closed-loop system that led to a fierce clash with disgruntled workers and the police, predating if not ushering in the A4 revolution. As Gou often criticised Taiwan's Covid policy, his deafening silence in this regard is even more intriguing.

Taiwan's reactions toward the A4 revolution need to be understood in the context of the island nation's strings of activities toward the international crises of democracy. In 2019, as Hong Kongers' protest movement against the proposed extradition to the mainland rose, Taiwanese enthusiastically joined the campaign and offered their support, thus making the island the most important overseas logistic support depot. In August 2020, as Thai students rose to challenge the junta government with street protests, several sympathy rallies emerged in Taipei. The Myanmar coup in February 2021 stimulated a wave of protesting and mobilising on the part of the diaspora communities in Taiwan, while Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 also launched another solidarity campaign in Taiwan.

Diaspora activism plays a role

Common to these cases is the threat to democracy, whether from abroad or from within, and these international crises resonate particularly with the Taiwanese not only because of geographical proximity, but also because they are prefigurative of Taiwan's own future - an embattled democracy facing an existential challenge.

Understandably, Taiwanese reacted strongly to Hong Kong's and Ukraine's emergencies, but were less enthusiastic about what happened in Thailand, Myanmar, and China. The horrendous scenario of imposing China's version of "one country, two systems", and the military invasion, were more experientially close and imaginable than military coups or coercive Covid-related restrictions.

Taiwan's international solidarity campaigns are also deeply affected by the presence and structure of diaspora communities.

Due to the lack of Thai students (in spite of numerous Thai migrant workers), Ukrainians, and Chinese students (in spite of marriage migrants), and their weak presence in Taiwan, the campaigns of these communities have found it difficult to reach out to broader support. By contrast, the more favourable migration regime for Myanmar Chinese and Hong Kongers, made it easier for them to settle permanently in Taiwan, thus allowing them to continue their diaspora activism.

...many overseas Hong Kongers, as well as the Taiwanese, had articulated a vision of global justice that connected the worldwide anti-authoritarian struggles.

Supporting universal values

Taiwanese reaction to China's A4 revolution also reflects the ever-changing cross-strait relationship. As said above, many Taiwanese participants found it necessary to explain the reasons why they endorsed the Chinese pursuit of freedom, knowing that a great majority of these Chinese would support the military operations to annex Taiwan.

Hong Kong's pro-democracy campaigners also faced the same question. The 2019 anti-extradition movement was drowned in the government-orchestrated chorus to support the police. If the Chinese had supported the police repression against Hong Kongers' effort to preserve their liberties, why should Hong Kongers care about the Chinese plight in lockdowns? If Chinese protesters were brutalised by the police in the A4 revolution, wouldn't it be a perfect case of poetic justice?

However, instead of subscribing to such narrow-minded schadenfreude, many overseas Hong Kongers, as well as the Taiwanese, had articulated a vision of global justice that connected the worldwide anti-authoritarian struggles.

Taiwanese's learning curve towards the Tiananmen Square incident might provide a clue here. Taiwanese were deeply impacted when tanks rolled into the square in 1989, and had held an outdoors commemorative event the following year. But what ensued was a gradual process of forgetting, because the Chinese tragedy turned out to have little impact on the island's own march toward democracy. As such, when the Tiananmen memorial rallies reappeared in 2011, it was largely due to the revival of Taiwan's student movement, and the widespread concern with China's growing threat to regional and global democracy.

... Taiwan's reception to the A4 revolution is better understood under the lens of the history of the island's pursuit of its own identity.

Conspicuously, the collective memory of the Tiananmen Square incident has evolved from being an event of nationalistic and patriotic significance, to that of supporting universal values. As such, Chinese nationalism dissipated and the June 4 rallies in Taipei became a meeting point for Hong Kongers, Tibetans, Uighurs, Falun Gong members, and so on, as Taiwan became more indigenised and democratised.

In short, Taiwan's reception to the A4 revolution is better understood under the lens of the history of the island's pursuit of its own identity. During the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, it was still possible for the Taiwanese to imagine themselves as both pro-democracy and pro-unification. Thirty more years later, such wishful thinking is no longer tenable.

This sea change in attitude explains why Taiwan's civil-society actors chose to react to the biggest incident of China's anti-government protests since the Tiananmen Square incident on "universal values", rather than national sentiment.

Simply put, for those Taiwanese who are concerned about the future of Taiwan's democracy, A4 revolution is an international issue comparable to the recent happenings in Thailand and Myanmar, but falling short of the attention wrought by the incidents in Hong Kong and Ukraine.