South Korea and America's Indo-Pacific strategy: Yes, but not quite

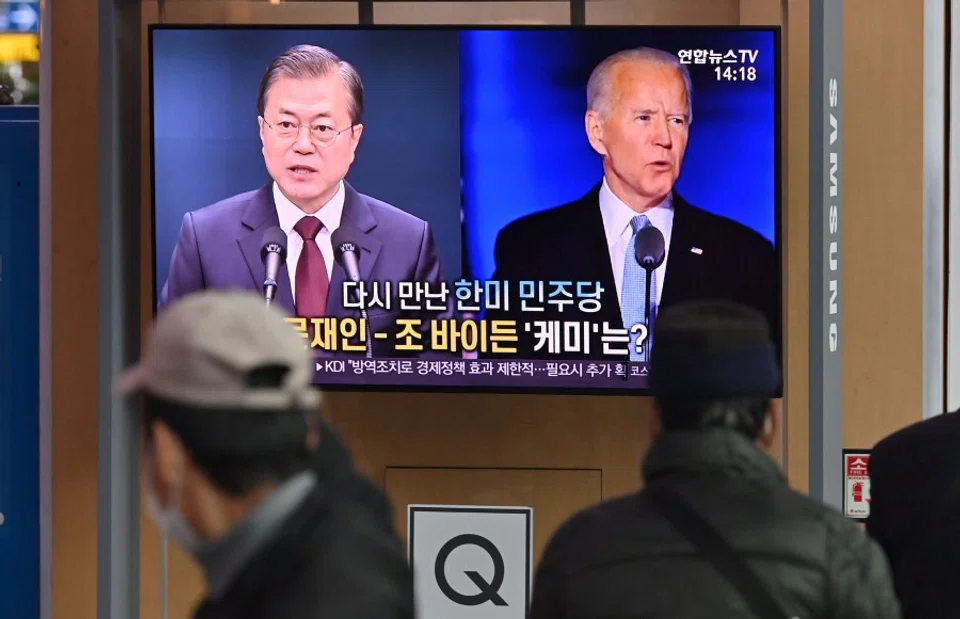

In a call with South Korean President Moon Jae-In on 11 November 2020, US President-elect Joe Biden emphasised that South Korea represented the "lynchpin of the security and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific region". It is too soon to comment on any possible variations that will appear in American policy towards Asia yet. But it seems likely that the "Indo-Pacific Strategy" - as detailed in the Department of Defense's 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report (IPSR) and State Department's Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) document - enjoys bipartisan support and will thus remain the centerpiece of US engagement with the region. This is also currently the consensus view among the Korean media and expert community.

... Seoul finds itself sandwiched between its US ally and its Chinese superpower neighbour. Throw in North Korea and Japan, and South Korea fits the moniker of being the proverbial "shrimp among whales".

It is therefore worth taking stock of how South Korea has responded to some of the core elements of America's Indo-Pacific strategy since its inception under the Trump Administration as part of the wider debate of the contentious introduction of the "Indo-Pacific" geopolitical concept.

The government of Moon Jae-In has shown a rather lukewarm embrace of the concept in contrast to enthusiasts such as the US, Japan, India and Australia (all members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad alignment). The Blue House has demonstrated studied reticence in adopting the Indo-Pacific concept itself and so far delivered little substantive backing for the US's Indo-Pacific strategy. President Moon has hesitantly endorsed Korean cooperation with Washington's Indo-Pacific strategy after much demurral, as reported in the Korean media around the 2019 Summit Meeting with President Trump. Seoul did not express interest in joining the FOIP or Quad.

Seoul's circumspection in lending full-throated support to the Indo-Pacific concept and the American policies that are attached to it stems from its precarious geostrategic position. Like many Southeast Asian countries, which have to navigate the tricky shoals of Sino-US rivalry, Seoul finds itself sandwiched between its US ally and its Chinese superpower neighbour. Throw in North Korea and Japan, and South Korea fits the moniker of being the proverbial "shrimp among whales".

South Korea's strategic room for manoeuvre is also limited by its diverging security and economic interests, which like many regional states, are centered on the US and China respectively - leading to a security-economic disconnect. This situation is further exacerbated by spiralling Sino-American strategic competition and the chaos caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Given this unenviable predicament, policy-makers in Seoul - like their counterparts in ASEAN member states - have sought to maintain an uneasy equidistance between the two competing regional superpowers and their respective Indo-Pacific Strategy and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) power plays. Among strategic analysts in South Korea, there is a consensus that the US-led Indo-Pacific narrative will accelerate and sharpen strategic competition in the region, and this accounts for the tepid response it received in government circles. For example, Moon Jung-In, a special adviser to South Korean President for foreign affairs and national security, indicated the "exclusivity" of the US-led Indo-Pacific strategy, such as excluding the Chinese government, as South Korea's chief cause for concern.

... Seoul has sought to avoiding "picking sides" in the great power geopolitical contest (notwithstanding its bilateral security alliance with the US), and has alternatively sought to emphasise economic regionalism, rather than security "blocs".

This has resulted in a diplomatic finessing that can be largely viewed as an attempt to placate its powerful ally, whilst avoiding direct support or participation in any of the more provocative aspects of American policy as they relate to the strategic contest with China. Instead, Seoul has deftly sought to side-step these by aligning its own "New Southern Policy" (NSP) (Sin Nambang Jeongchaeg) - now upgraded to Sin Nambang Jeongchaeg Plus - with the US Indo-Pacific strategy.

At the joint press conference following the 2019 Korea-US Summit, Moon stated that two sides "have agreed to put forth harmonious cooperation between Korea's New Southern Policy and the United States' Indo-Pacific strategy". In this way, South Korea has pointed to convergences between the NSP and Indo-Pacific strategy. The NSP also has the virtue of connecting with "ASEAN centrality" given its primary South East Asian focus.

Kim Hyun-Wook from the Korea National Diplomatic Academy suggests that South Korea "promote functional involvement where we [South Korea] and the United States have common interests, such as strengthening cooperation between New Southern Policy and Indo-Pacific strategy... rather than joining a monolithic form of Indo-Pacific strategy".

Quite similar to ASEAN's approach, Seoul has sought to avoid "picking sides" in the great power geopolitical contest (notwithstanding its bilateral security alliance with the US), and has alternatively sought to emphasise economic regionalism, rather than security "blocs". Lee Jae-Hyun, a Senior Fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, claims that "It is a desirable strategy for Korea to avoid formal declarations such as cooperation with the Indo-Pacific strategy or Belt and Road Initiative", whilst harmonising the geostrategies of superpowers with South Korea's own NSP-plus. It has however joined the more inclusive Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), an ASEAN-driven free trade agreement that incorporates several other Indo-Pacific states. It has also signalled its willingness to join the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), should the US chose to rejoin what is currently the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP involves 11 countries, including four ASEAN members - Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam.

Thus, Seoul has been highly circumspect in its support for the US-led Indo-Pacific strategy (or BRI) and eschewed joining the FOIP or Quad, preferring to emphasise its own NSP-Plus initiative. It has directed its energies toward economic regionalism efforts such as RCEP, and possibly, in the future, the TPP. As geopolitical competition heats up, especially in the security arena, South Korea will continue to face tough challenges in navigating this tense diplomatic environment.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as Fulcrum Commentary 2020/189 "South Korea and America's Indo-Pacific Strategy: Yes, But Not Quite" by Thomas Wilkins and Jiye Kim.