Singapore history: A tale of separating and connecting (Video and text)

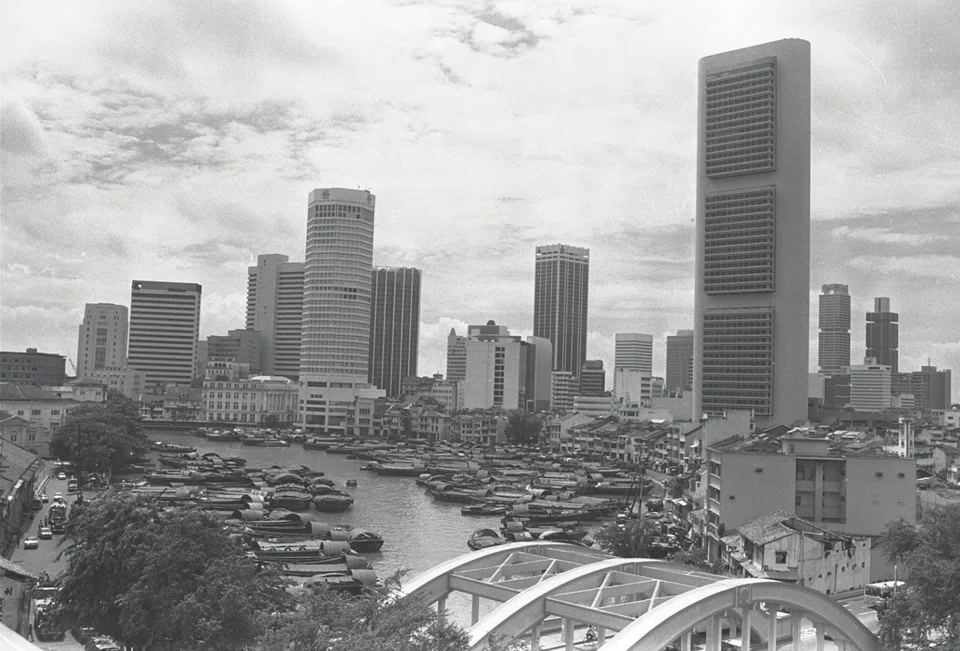

The day Singapore was separated from Malaysia in 1965 was for some the end of the idea of Malaya. To others, it was a cause for celebration: Singapore was independent. That separation is traceable to 1819 when the English colonial traders set up a post in Singapore, to enable the East India Company in Calcutta to connect more directly to the China coasts.

At that time, the established empire was China and the rising empire was British India. Penang at the head of the Malacca Straits had demonstrated how valuable the route was for Indian opium and the tea trade of China. Singapore provided an invaluable connection.

Twenty years later, the British established the colony of Hong Kong and opened the Treaty Ports in China. The imperial relationship was reversed. The rising empire was now more powerful and the colony in Hong Kong, together with Treaty Ports like Shanghai, were its merchant garrisons. Hong Kong was directly connected to China and its Chinese residents saw how they could benefit from having a different operating system in their country.

In contrast, from Raffles and Farquhar to Crawford, Singapore was separated from the larger Malay world controlled by the Dutch. With the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, these two drew a line of separation in the Malacca Straits. That helped British country traders and the East India Company to strengthen their connection to China. Many others benefited from the convenience and also used Singapore to develop local markets. But the emphasis was on the maritime links between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

Thus the rapid rise of the Chinese population was not accidental but was to do with improving Singapore's position with China.

After the 1850s when Hong Kong and Shanghai dominated the China trade, Singapore's role had to change. It sought closer relations with the Malay states and, after the intervention in the Perak wars (1870s), became effectively the capital of a confusing entity based on a mix of direct and indirect rule that they began to call Malaya.

This was in part because the British global empire was over-extending northwest of India and competing with French and German challenges in Africa and the South Pacific. It was left largely to local officials and the merchant houses of Singapore to reconnect with the Malay world. Some of their initiatives were very profitable but the overall relationship with the Malay states was never comfortable. A key reason was that Singapore was linked to the China trade from the start and depended on its Chinese to support its plans.

Thus the rapid rise of the Chinese population was not accidental but was to do with improving Singapore's position with China. The British strengthened that connection by bringing Baba Chinese from Malacca to help them deal with other Chinese already active in the neighbourhood, especially those who found it advantageous to use the colony's free port facilities.

These local Chinese, with help from the Malacca families favoured by the British, adapted successfully to the emerging system. After the opening of China, large numbers of newcomers came to supply the labour force needed following the end of slavery. Most used Singapore as the transit port to the Malay states and various parts of the Dutch Empire but many stayed in the colony.

It was in the British interest to encourage cooperation between Malays and Chinese, but the long-term effect of Singapore's separation were clear to the Japanese.

Thus, for the British, managing Chinese in the colony was always important. A Chinese protectorate had to be established to deal with the growing community. By the turn of the 20th century, the problem was made more difficult when many became politically conscious. When Sun Yat-sen and his anti-Qing rebels were active, Singapore provided supporters for their revolution. That nationalism was now an issue of politics and security.

I am reminded that supplementing the record of what the British had achieved in the first 100 years was Song Ong Siang's book on 100 years of the Chinese, a landmark story of their multivarious involvement in Singapore's development. It was also when these Chinese sought a bigger role in the city's governance. For the British, they began to realise that managing the Chinese was making the task of connecting with the Malay States more complicated.

What was remarkable, however, was that the generations of people in Singapore who lived through the efforts to reconnect seemed to have grasped the idea that being connected to the distant and separate from the near was something they simply had to learn to deal with.

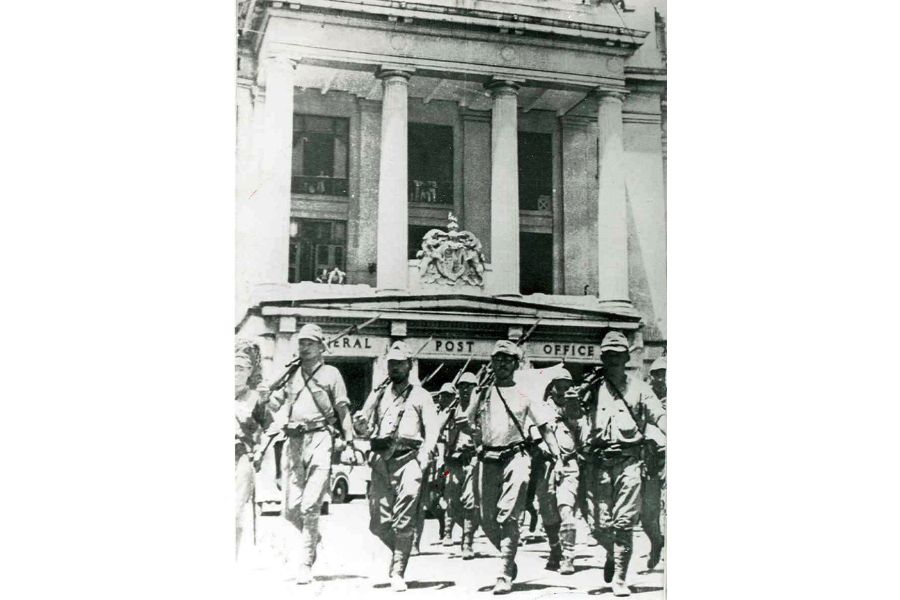

It was in the British interest to encourage cooperation between Malays and Chinese, but the long-term effect of Singapore's separation was clear to the Japanese. When they renamed it Shonan in 1942, the only place given a Japanese name, they saw it as the region's imperial base. They sought the trust of the Malay-Indonesian world and helped the Indians to build the Indian National Army to liberate India from British rule. But they did not trust the Chinese who saw them as the enemy and were willing to fight them together with the British. Thus, although briefly, the different local communities were further separated.

The connections that the British tried to establish from the late 19th century did not work. After the war, the Malayan Union proposed was not acceptable and the Malayan Communist Party supported mainly by Chinese turned against them. Also, the Federation of Malaya was not the British Malaya that they had hoped for. To Malay leaders, that was always Tanah Melayu, Malay land. While they needed to make concessions to other communities in order to gain the country's independence, they rejected the connections that characterised British Malaya.

In that context, the separation of 1965 should not have been a surprise. The hasty efforts to connect British Malaya to Greater Malaysia were more like improvisations and failed to overcome the disparate developments that had made reconnecting difficult time and again.

What was remarkable, however, was that the generations of people in Singapore who lived through the efforts to reconnect seemed to have grasped the idea that being connected to the distant and separate from the near was something they simply had to learn to deal with.

Singapore has to rebuild connections with its ASEAN neighbours to enable that organisation to deal with the rivalries involving new great powers.

To emphasise Singapore's distinctiveness, the Hong Kong experience is illuminating. There the close connections from the start with its China hinterland had led to different kinds of adaptations. Its largely Chinese population never stopped being engaged in all of China's affairs. On balance, it could be argued that they had balanced two systems under the shadow of China. Thus when the British left, that balance was lost and the China connection became overwhelming.

For Singapore, the opposite happened. Separating from the near had given the British full control of the China-British India relationship. By 1965, the people of Singapore had internalised the early imperial linkages. They set out to build on that heritage to seek its place as a global city and turn its plural society into a viable and prosperous state.

There are now new challenges. Two are obvious. China had learnt that neglecting its south had resulted in its near-collapse. No longer divided and weak, it will not allow its coasts to be vulnerable again. It expects its relationship with Singapore to reflect that understanding. The other concerns the relations with a new Southeast Asia from which Singapore cannot be separated. Singapore has to rebuild connections with its ASEAN neighbours to enable that organisation to deal with the rivalries involving new great powers. Both challenges require much rethinking, not least about how connecting and separating could be managed under these conditions.