Lost in translation - Trans-lost-ation!

Digital transformation expert Kwek So Cheer was confident in his grasp of the Chinese language - until his work brought him to China in 2012.

Trans-lost-ation. That's how I felt when I first worked in China in 2012. It was an unexpected work assignment from the consulting company which I had joined right out of school. I was a partner based in Singapore and did have some doubts initially to leave the comforts and familiarity of home. I knew that the assignment would be a challenging one which could potentially kill a career which I had spent many laborious years building up. I also had to leave a team with which I had bonded, that at its peak was 400-plus in strength.

Moving on to another project in a foreign land, with a hostile client that was in the process of terminating a contract with us seemed like a stupid idea. Many well-intentioned friends strongly advised me against it. However, those words were lost on me. I took a leap of faith and crossed the South China Sea, taking up the role of Project Delivery Partner of an enterprise resource planning implementation project with a Fortune 500 tech company based in Shenzhen, China.

I still remember my first client meeting vividly. It was a room filled with at least 50 people. The topic was a project issue which needed resolving. There were a few of us who were tagged as expatriates with professional translators assigned. I was offered a device with earphones to plug into, where simultaneous translation service was offered. Until then, I had been quite confident of my Chinese ability, having gone through Dunman High, a Singapore Special Assistance Plan school which offers Chinese at a higher level. I was also actively involved in Chinese drama during my Hwa Chong Junior College days, and even held a lead role in a Chinese theatre performance under the direction of Singapore veteran theatre director Han Lao Da (韩劳达) during the 1992 Singapore Arts Festival. Why would I need Chinese-English translation? Furthermore, I was eager to make a good impression on the team and the client. As such, I politely declined the offer.

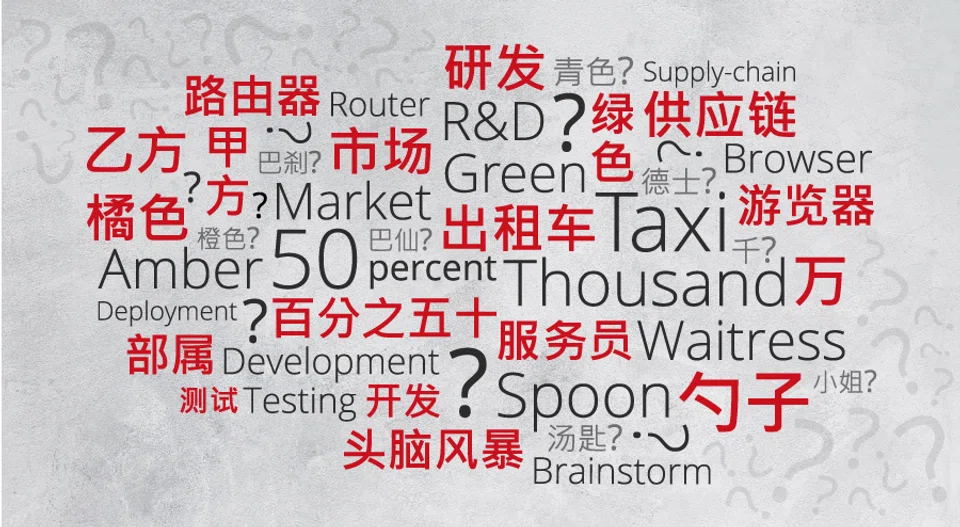

...while 巴仙 (ba xian), the transliteration of "percent", is widely used by Southeast Asian Chinese, the term sounds the same as 八仙, meaning the Eight Immortals in Chinese legend.

Pride indeed goes before a fall. And the fall was excruciatingly humbling. I couldn't understand at all what was being discussed. Somehow, that same pride that had me refusing the translators also stopped me from going back to them to beg for the earpieces. I had to eat humble pie and scribble furiously what I assumed I had heard in my notebook, using a mixture of Chinese characters and Hanyu Pinyin (romanization system for Chinese characters). Or rather, Hanyu Pinyin with a sprinkling of Chinese characters mixed in.

The loss in translation was two-way. During my discussions and meetings with the local Chinese, whenever I said 50巴仙 to mean 50 percent, I would be greeted with blank stares. It turned out that while 巴仙 (ba xian), the transliteration of "percent", is widely used by Southeast Asian Chinese, the term sounds the same as 八仙, meaning the Eight Immortals in Chinese legend. So the other party was trying to understand why I would bring up deities in a discussion. Later on, I learnt that I should say 百分之五十 (bai fen zhi wu shi, or literally 50 parts out of 100) instead, to avoid sounding holy.

Back then, Didi, the equivalent of Grab in China, had not yet been invented, and booking transport was done through the good old phone booking systems. Asking for help to book a 德士 (de shi, taxi) was another example of being lost in translation. I quickly learnt that booking a 出租车 (chu zu che, taxi) was a more effective way to get my ride. This would prove to be a common theme, where numerous Chinese phrases we use in Singapore are not understood in China. Another example would be 巴刹 (ba sha, market), which is a common term in Singapore but is referred to as 菜市场 (cai shi chang) in China. I quickly realised that I was operating in a totally different market.

I also had a rather "colourful" time going through project status with the team. We used three colours for different statuses: green, amber, and red. I learnt that green is not 青色 (qing se) but 绿色 (lü se), while amber is not 橙色 (cheng se) but 橘色 (ju se). At least I got red correct - 红色 (hong se) - which was the colour of my face each time I embarrassed myself with my Mandarin "prowess". Also, in China, figures are reported in 10,000 (万/wan), whereas in Singapore, numbers are expressed colloquially in 1,000 (千/qian), an influence of the English language. I had so much trouble trying to mentally translate 万 to the actual number in my head, and there were times when these numbers were also lost in translation.

Addressing the waitresses as 小姐 (xiao jie, miss or little sister ) only attracted cold stares, which made me feel like they were about to run into the kitchen for a pair of knives to stab me with. It turned out that the term refers to ladies of the night.

Also, at first, having a relaxing meal at a restaurant was anything but "relaxing". Addressing the waitresses as 小姐 (xiao jie, miss or little sister) only attracted cold stares, which made me feel like they were about to run into the kitchen for a pair of knives to stab me with. It turned out that the term refers to ladies of the night. Instead, I learnt to address them with the more dignified 服务员 (fu wu yuan, wait staff). And asking for a 汤匙 (tang chi) would not get me a spoon, but into hot soup. Because in China, a spoon is called 勺子 (shao zi).

As the person responsible for delivering a multi-million dollar project involving analysis, development, testing, deployment, and R&D, I vividly recall the embarrassment I felt when I couldn't articulate any of those phases in the project life-cycle in Chinese: 分析 (fen xi, analysis), 开发 (kai fa, development), 测试 (ce shi, testing), 部属 (bu shu, deployment), and 研发 (yan fa, R&D). None of these terms were taught in school, and terms such as router (路由器, lu you qi), browser (游览器, you lan qi), and supply-chain (供应链, gong ying lian) were terms that I had to pick up. I discovered that most of these were direct translations, and couldn't help being amused at some, like 头脑风暴 (tou nao feng bao, a literal translation of "brainstorm").

To ensure that I fully mastered the language, I had to consciously refrain from mixing English into the Chinese sentences when I was speaking. This took tremendous effort, especially when I was so used to adding Singlish conjunctions like "and then" (instead of "and") and "but then" (instead of "but"). Of course, other common Singlish sentence enders like "lah" and "meh" that complement almost any sentence in any casual conversation in Singapore had to disappear when talking to the Chinese. I took my efforts seriously. Before my meetings with the client's senior management, I rehearsed daily with my team with handwritten Chinese notes, going over potential questions that could be asked and what the answers would be, in perfect Chinese.

However, even now, negotiating contracts in Chinese is by far the biggest challenge. Despite having a team that supports me in drafting contracts, I insist on understanding every line in each contract, as I am the one ultimately responsible. It is in negotiating contracts where the slightest mistakes made in translation could be costly. Basic terms such as 甲方 (jia fang, Party A) and 乙方 (yi fang, Party B), in my case often meaning Client and Supplier respectively, are easy to mix up, and if I do, it might be disastrous.

Looking back, I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked in an environment that was entirely out of my comfort zone, which forced me to adapt and grow. I am proud to say I have learnt a thing or two about the "real deal" in China, having been immersed in it since 2012. I knew I had reached a certain level of proficiency when during one of my visits back home in Singapore, after ordering some dishes in a local restaurant, the waitress asked me how long I was visiting and which part of China I was from.

Yes. I do not get lost in translation with the Chinese any more. No more trans-lost-ation.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)