Maternity wards are latest victim of China’s falling birth rate

China’s low fertility rate has put maternity departments in a tough spot, with some reducing the number of beds or diversifying their businesses to survive.

(By Caixin journalists Zhao Jinzhao, Pan Rui and Wang Xintong)

China’s hospital maternity wards have fallen victim to the record-low birth rate and are facing a similar fate as preschools as more and more wards close or downsize as demand for obstetrics declines.

As of March, at least 35 public medical institutions in China had stopped delivering newborns over the past three years, with some ten doing so in the first quarter this year, according to a count by Caixin.

But those are just the instances that were publicised, the true extent of the closures is greater: doctors in Shanghai and Guangzhou told Caixin that several general hospitals in the two cities have quietly closed their maternity departments in recent years.

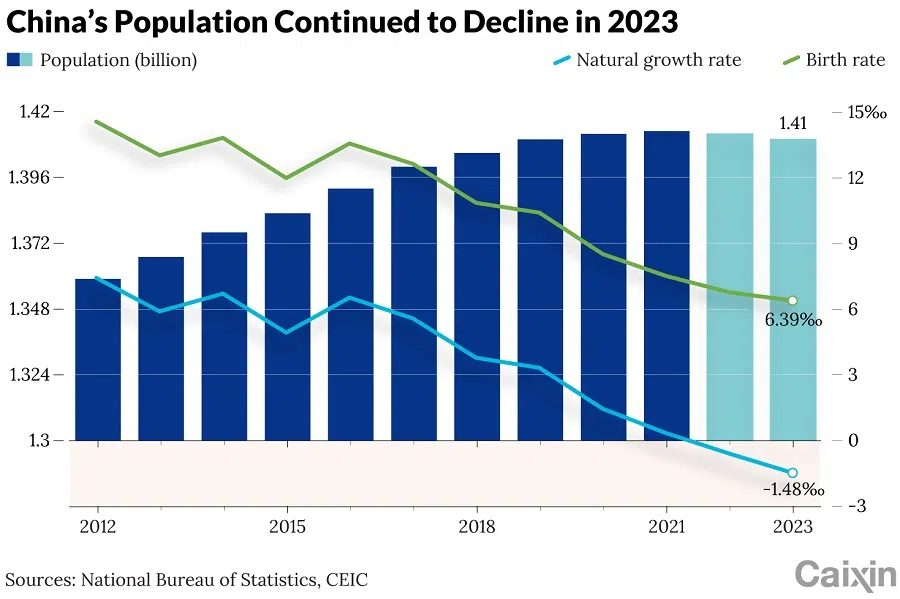

The pace of closures has accelerated since 2023, when China’s population shrank for the second year in a row and the birth rate hit a new low. Many maternity departments or specialised hospitals are struggling to stay afloat, with some reducing the number of beds or diversifying their businesses to survive. More obstetricians are leaving the field amid a bleak outlook, sources told Caixin.

The pervasive issues plaguing obstetrics were thrust into the spotlight in February when Duan Tao, a professor and director of obstetrics at Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, took to social media pleading for action to “save obstetrics”. Duan’s plea raised concerns about the future of care for women and babies during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period.

Li Li, an obstetrician at a hospital in North China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region, told Caixin that she is worried that obstetric services are not just shrinking but vanishing in some areas.

The crisis affecting obstetrics could have wider implications, a senior doctor in the field told Caixin, as maternal and neonatal mortality rates are a core indicator of a country’s level of economic development and population health.

The senior doctor also warned that it would be difficult for the specialty to grow again if its foundation was undermined by a slip in demand for births and policy issues.

China’s maternal and child health service system faces “new tasks and challenges” during the implementation of the three-child policy...

Amid the growing concern, the National Health Commission (NHC) issued a circular in late March urging public medical institutions offering obstetrics services to continue providing them “in principle”.

The circular requires the institutions planning to close their maternity wards to consult widely with pregnant women and mothers of newborns, and to consult in writing with lower-level authorities.

China’s maternal and child health service system faces “new tasks and challenges” during the implementation of the three-child policy, an NHC official told Caixin. “We will strictly adhere to the safety bottom line and make every effort to ensure the safety and health of mothers and children.”

Falling birth rate

China saw a short-lived baby boom in 2016, when the government officially dropped its one-child policy and allowed married couples to have two children. Since then, the number of newborns has declined every year, even after the government made another major shift in 2021, raising the number of children allowed per family to three. The following year, China’s population fell for the first time in 60 years as its birth rate dropped to a record low.

The easing of the policy only encouraged couples who want to have children, said Duan, adding that among the wider population of childbearing age, the willingness to marry and have children remains low.

The reluctance to have children is greater in large cities, where sky-high housing price-to-income ratios, tough educational pressure and costs, and a less-friendly fertility environment have dampened the desire to raise kids, Liang Jianzhang, co-founder of online travel platform Trip.com Group Ltd. and a population economist, previously said in an opinion piece published by Caixin.

From the beginning of 2023 to March this year, around two dozen medical institutions, including tertiary hospitals, announced they would discontinue obstetrics services...

Available data “leads us to conclude that China’s big cities have the highest child-rearing costs of anywhere in the world, in turn leading to the lowest fertility rates in the world”, Liang said.

The low fertility rate has put maternity departments in a tough spot. They must bring their deliveries up to a certain number to recoup costs: If a large hospital has fewer than 1,000 deliveries a year, its maternity wing will struggle to maintain operations, a health worker at a public hospital in Guangzhou told Caixin.

From the beginning of 2023 to March this year, around two dozen medical institutions, including tertiary hospitals, announced they would discontinue obstetrics services, according to a count by Caixin.

Hospitals in China are divided into three classes, with tertiary being the best and typically equipped with the greatest resources and served by the country’s top doctors.

Cutbacks

Some hospitals that offer obstetrics services are reducing the number of beds to save costs.

Li said the hospital where she works has had to reduce its number of beds because deliveries are down 80% to 90% from their peak. The hospital also faces competition from nearby larger hospitals, which often have better doctors and equipment, she said.

But larger hospitals are also suffering. The Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, one of the city’s top obstetrics hospitals, has seen its deliveries fall to just over 20,000 from a peak of 34,000 in 2016, Duan said. He estimated that the public hospital has cut as many as 100 beds due to falling demand.

A doctor at a private general hospital in Shanghai said births had nearly halved from their peak.

The falling birth rate is likely to hit private hospitals specialising in obstetrics harder than state-subsidised public hospitals. Many private institutions are still struggling following the Covid-19 pandemic, with some already forced to close after operational pressure mounted.

Last year, Harmonicare Medical Holdings Ltd., which once billed itself as “the largest private obstetrics and gynecology specialty hospital group in China”, came under the spotlight after reports that a Beijing hospital owned by its brand HarMoniCare was forcing pregnant women, new mothers and their babies to be transferred to another hospital due to huge rent arrears. Harmonicare Medical was delisted from the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2021 after sustaining losses and closing several hospitals.

The number of deliveries is linked to doctors’ income, which generally consists of a basic salary, performance bonuses and other benefits.

Other hospitals have chosen to diversify their operations in order to survive. In provinces such as Sichuan and Guangdong, some maternal and childcare hospitals have been opening daycare centres — including “inclusive institutions” that can receive government subsidies, domestic media reported. Others have developed VIP businesses or expanded their operations into new areas such as medical cosmetic services.

Exodus of obstetricians

The number of deliveries is linked to doctors’ income, which generally consists of a basic salary, performance bonuses and other benefits. Qin Mei, a former obstetrician at a tertiary hospital in Guangdong province, once received a monthly bonus of just over 1,000 RMB (US$138) after the number of deliveries dropped.

This didn’t match her intense workload, said Qin, which would include regular night shifts from 5:30 pm to 8 am, without any breaks.

“Who wants to face such a big risk, work day and night, and end up with such a low performance (bonus)? How can the obstetrics department keep people if they want to?” Duan asked.

Obstetrics is considered a particularly high-risk specialty given that doctors are caring for pregnant women, new mothers and newborns.

As a result, maternity departments have seen an exodus of doctors.

Obstetricians switching careers could threaten maternal health and undermine the country’s efforts to boost births...

A few months ago, Qin changed her job. “I still want to do some clinical work, but I don’t want to do this kind of high-risk, high-intensity work anymore.”

But this may create new problems. Obstetricians switching careers could threaten maternal health and undermine the country’s efforts to boost births, a doctor in the field told Caixin.

The loss of professionals comes as more women are getting pregnant at an older age or through in vitro fertilisation. This, along with other special circumstances, has made it more challenging to reduce the maternal mortality rate and put higher demand on obstetricians’ capacity and the overall quality of services provided by maternity departments, several doctors told Caixin.

They called for more policies to be introduced to support the development of obstetrics, including ways to improve the salary distribution system for doctors and initiatives that could increase the number of people who want to have children.

(Li Li and Qin Mei are pseudonyms.)

Zhou Yumeng contributed to this story.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “In Depth: Maternity Wards Are Latest Victim of China’s Falling Birthrate”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)