When good intentions fail: The rise and fall of China’s community canteens

Community canteens were meant to offer affordable meals for seniors, but poor planning, misaligned incentives, and market pressures turned a good policy idea into a cautionary tale of failed implementation. Lianhe Zaobao’s China Desk explores “big pot 2.0”.

With China becoming an ageing society in recent years, community canteens have sprung up across urban neighbourhoods to meet the dietary needs of the elderly by offering affordable meals, with over 1,700 new canteens registered in 2023 alone. However, there has been a heated public debate over whether these canteens are truly a welfare initiative or a political showcase, with some drawing parallels to communal dining (大锅饭) of the planned economy era and expressing concerns about a rollback of reform and opening up policies.

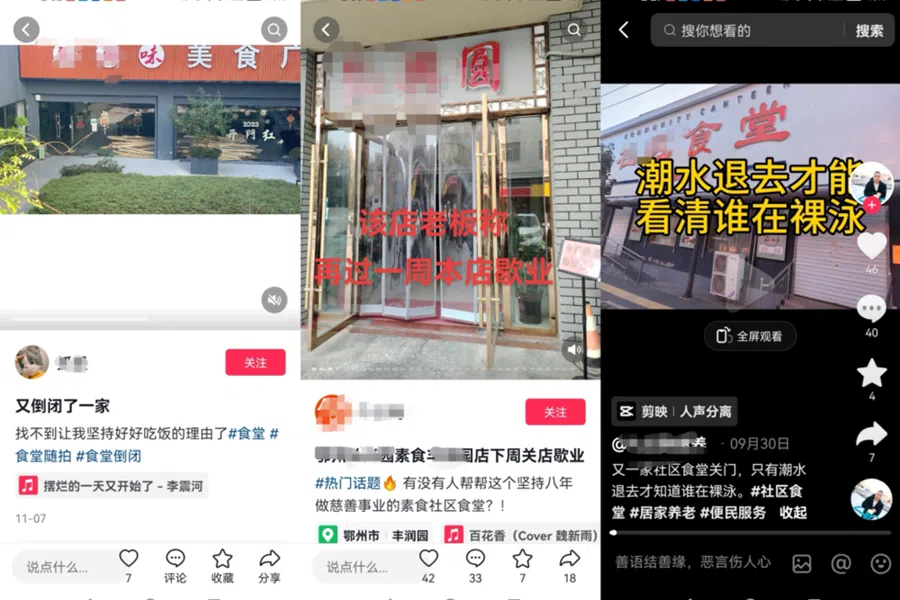

Yet the initial boom has cooled in the past two years. With shrinking government subsidies, intense involution and the loss of consumers, many community canteens have been forced to shut down, some after less than two months in operation.

The rise of community canteens in China can be traced back to a directive issued by central government ministries in late October 2022.

A new ‘planned economy’?

The Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, along with the Ministry of Civil Affairs, launched a pilot to create “complete communities”, aiming to integrate local service infrastructure. This initiative prioritises facilities for the elderly and children, and calls for one-stop amenities like convenience stores, canteens and express delivery points.

Community canteens gained prominence among local government initiatives. This, alongside provinces like Hubei reviving “supply and marketing cooperatives”, and the All China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives recruiting civil servants, sparked debate about a return to a planned economy.

... they are simply offering the elderly an additional option, and are not meant to replace existing dining establishments. — The Paper editorial

Towards the end of the three-year Covid-19 pandemic, community canteens began springing up across China in the second half of 2022. By the following year, there were over 6,700 community canteens operating nationwide. These canteens not only filled first-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, but also covered western and central regions such as Chengdu and Wuhan.

Ming Pao reported that the typical model of a community canteen involves funding from local subdistrict offices, with operations entrusted to government-approved catering providers, and prices set slightly below those of regular restaurants. In some areas, these are even branded as “state-run canteens”.

Amid public speculation, grassroots officials clarified that today’s community canteens are part of broader community services, not a return to the old “communal dining” model, and are primarily intended to serve the elderly by addressing their daily meal needs.

The Paper also published an editorial noting that community canteens carry significant meaning for China’s ageing society, especially during repeated Covid outbreaks. It stressed that they are simply offering the elderly an additional option, and are not meant to replace existing dining establishments.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong commentator Johnny Lau analysed that, due to China’s economic contraction, local supply chains for essential goods and services may face strain, and officials must prevent potential crises that could threaten social stability. In this context, “state-run canteens” could serve as a contingency tool for resource allocation and community management.

The ‘state advances’ while the ‘private sector retreats’?

Frank Xie, a professor at the University of South Carolina Aiken, argues that both community canteens and supply and marketing cooperatives are state-owned monopolies that could gradually take control of supply chains and agricultural products, manipulate prices, and squeeze out small private enterprises, markets, and restaurants, reflecting a broader trend of the “state advances, while the private sector retreats” (国进民退).

... these canteens were able to offer affordable meals — such as one meat item and two vegetable items for 12 RMB (US$1.68), or two meat items and one vegetable item for 15 RMB — thanks to local government subsidies or rent reductions...

Taiwanese media, citing a Beijing academic who declined to be named, noted that while these canteens primarily serve the elderly and do provide convenience and affordable meals, it remains to be seen whether local governments can expand and sustainably fund the operation of community canteens as local finances in China continue to deteriorate, especially after significant funds were consumed by mass Covid testing.

As expected, the unsustainable nature of community canteens has become increasingly evident. According to reports from Sing Tao Daily and Taiwanese media, community canteens in cities such as Beijing, Xi’an, Shenyang, and Hangzhou have shut down since last year.

The reports asserted that initially, these canteens were able to offer affordable meals — such as one meat item and two vegetable items for 12 RMB (US$1.68), or two meat items and one vegetable item for 15 RMB — thanks to local government subsidies or rent reductions, which attracted not only elderly residents but also younger people. However, as local governments faced mounting fiscal pressures, some canteens lost their subsidies and could no longer offer low-cost meals, leading to a decline in customers and ultimately, closure.

Difficulties in operation

The operational struggles of some community canteens had already caught the attention of some state media as early as last year.

In Jiangsu’s Suzhou, although 2,059 community canteens had been established, only 913 were actually in operation, with half of them running at a loss.

Banyue Tan (《半月谈》), a publication under Xinhua, reported that in one central province, six out of nine or over 60% of such canteens were operating at a loss. In Jiangsu’s Suzhou, although 2,059 community canteens had been established, only 913 were actually in operation, with half of them running at a loss. One key reason cited was that far fewer elderly residents were coming to the canteens than expected.

Some community canteens have also been criticised for missing their target demographic and engaging in “over-generalisation of welfare” (福利泛化), leading to underwhelming operational and service outcomes.

According to research by Wang Defu, associate professor at Wuhan University’s School of Sociology, Suzhou’s community canteens were theoretically designed to serve 120,000 people, but only served 24,000 meals last year. In Wuxi’s Yixing, community canteens served a daily average of around 3,100 people, just 1.22% of the total elderly population.

Professor Lu Dewen, also from Wuhan University, pointed out that local governments generally offered one-off construction and operational subsidies to community canteens, and that if these canteens were built but did not serve its purpose, it would lead to a waste of fiscal resources. Lu warned that “if community canteens are too densely located, they might put pressure on nearby restaurants by creating competition, causing new employment issues.”

Research also found that some more developed areas engage in policy competition, leading to “over-generalisation of welfare”. Wang stated that “community canteen prices were already low. Some areas proposed free meals for the elderly, when in fact many elderly are capable of paying. This contradicts the fundamental welfare principle of ensuring a safety net.”

Closures not due to lack of elderly, but inadequate services

One Chinese self-media commentator noted that most residents in their neighbourhood were over 70, with children who did not live with them, which meant that even the issue of what to eat was a cause of concern.

“The community canteens that have survived are run by bosses with significant catering experience, who can offer a great variety of dishes… but there are just a handful of such dedicated operators.” — a self-media commentator

They observed a neighbourhood community canteen initially thriving, packed with elderly and working patrons who found it highly convenient. However, its business gradually declined after the initial buzz, closing this spring. The owner said, “The elderly have low spending power and demand varied dishes — there was no point continuing!”

The commentator pointed out five reasons for the poor performance of community canteens: a lack of variety in dishes, inadequate service awareness, intense competition in the catering industry, high labour costs and a narrow customer base. “The community canteens that have survived are run by bosses with significant catering experience, who can offer a great variety of dishes… but there are just a handful of such dedicated operators.”

The catering industry at present is one of the most competitive sectors in China — especially with the big three catering platforms Meituan, Ele.me and JD.com engaging in price wars. Many children of these elderly order meals via these platforms for their parents.

Shifting intentions

The commentator noted that many elderly with mobility issues cannot access community canteens, which lack delivery services due to minimal staffing. This reliance on walk-in customers contributes significantly to their closures, as “it’s not that the elderly don’t want to patronise us; it’s that they are unable to do so.”

A community worker revealed some canteens were established merely to “check off a box” for superiors, lacking proper research into elderly needs.

A community worker revealed some canteens were established merely to “check off a box” for superiors, lacking proper research into elderly needs.

The financial news account “Not Hung Up on Finance” (不执着财经) recently highlighted that many community canteens, seeking financing, enticed the elderly to buy prepaid cards with bonus offers. However, due to poor management, owners often went out of business within three months, leaving seniors with worthless cards. This news quickly spread, eroding trust in canteens and drastically reducing patronage in other communities.

On the surface, the closure of community canteens was blamed on uninspired menus and awkward pricing. But beneath that lies a deeper tension between public welfare and market forces. Initially supported by government subsidies and not built for profit, these canteens struggled to adapt as funding dried up and operations remained static. In a sluggish consumer market, they couldn’t compete, becoming little more than a flash in the pan.

Without adjusting to market realities, the model is unlikely to endure. The so-called “Big Pot 2.0” experiment may resurface briefly, only to fade again under the weight of limited funding, overstretched operators and ineffective management.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “大锅饭2.0:钱没了人跑了锅砸了?”.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)