Southeast Asia: A hotspot for Chinese enterprises in the post-pandemic era?

As tensions between the US and China intensify and global supply chains undergo reconfigurations, Chinese businesses are seeking opportunities amid the crisis, heading out to Southeast Asia at a faster pace.

Alibaba, ByteDance, and Tencent have all set up their regional headquarters in Singapore last year, while Huawei announced its investment in a 5G innovation centre in Thailand last September.

Tencent Cloud opened its first cloud computing data centre in Indonesia in April, while SF Express acquired a majority stake in Kerry Logistics in February with the intention of gaining a foothold in the Southeast Asian market.

Traditionally, China's overseas ventures were infrastructure construction projects spearheaded by state-owned enterprises.

But the more recent wave of south-bound Chinese firms are from the private sector, with many focused on adding value to the daily lives of users.

Their product offerings include familiar names such as video platform TikTok, Tencent's mobile game platform PUBG Mobile and others.

The rapid advancement of China's information and communication technology industry has helped these companies build distinctive strengths.

The decline in bilateral ties between the US and China created stumbling blocks for Chinese businesses in their forays into Western markets. Inevitably, they have turned to the less developed Southeast Asia, which also holds immense potential.

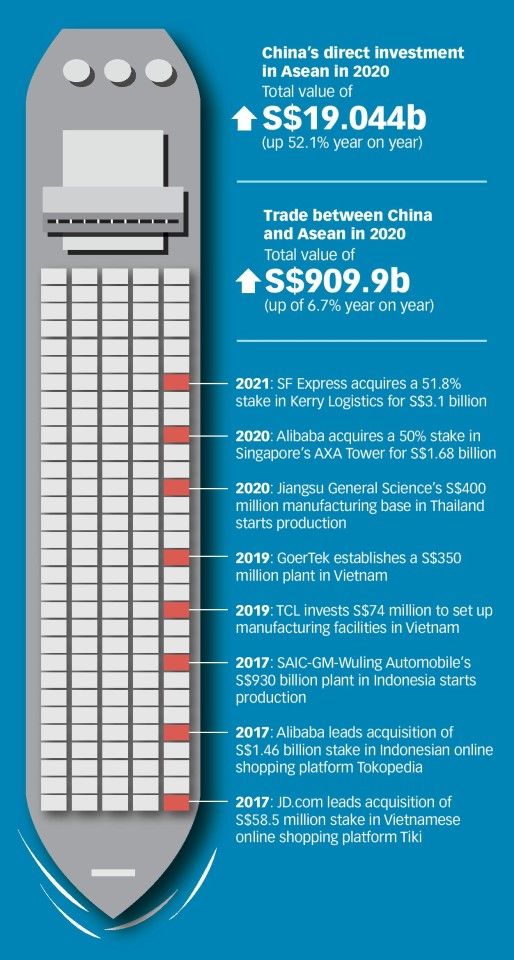

According to data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global foreign direct investment in 2020 plunged 42% to an estimated US$859 billion.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which consists of ten member countries, saw foreign direct investment fall 31% over the previous year.

Data from China's Ministry of Commerce showed that Chinese investment in ASEAN came up to US$14.36 billion, an increase of 52.1% year on year. The top three recipients of Chinese investment were Singapore, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

Widely seen as the third biggest market in Asia after China and India, ASEAN is home to 660 million people as well as a growing middle class.

Xu Ningning, executive president of the China-ASEAN Business Council, pointed out that Chinese investment in Southeast Asia can be categorised into five types: infrastructure building under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), manufacturing and assembly, engineering projects, real estate, as well as e-commerce and digital economy.

Mr Xu observed that the diversity of ASEAN nations and their varied stages of development have created a wealth of opportunities for Chinese enterprises.

The resources and industrial sectors of China and ASEAN are complementary, and their geographic proximity is also giving a boost to trade cooperation in the post-pandemic era.

Mr Xu cited the example of Singapore as a global financial services hub that can serve as a springboard for Chinese companies going global.

Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand are manufacturing and assembly bases that offer Chinese firms a way of circumventing punitive tariffs for exporting to the US and Europe.

Indonesia, Brunei and Laos are home to a number of ventures involving mines, wood, and other natural resources under the BRI.

Chinese real estate ventures are concentrated in Johor Bahru in Malaysia, Bangkok in Thailand, and Phnom Penh in Cambodia, while e-commerce investors are drawn to Indonesia and Vietnam.

Riding on the boom in e-commerce and e-payments in the region, Chinese logistics firm Best Inc had reportedly fulfilled some 73.59 million orders in Southeast Asia last year, a growth of 738% over the previous year.

UnionPay International announced a cooperative agreement with Vietnam's Military Bank to issue 600,000 virtual bank cards, offering online card applications and QR code payments in Vietnam.

Shanghai-based Ice Kredit is one of many Chinese firms eager to gain a foothold in Southeast Asia. A fintech company specialising in risk management and credit assessment, it offers loan approval and collection through the use of artificial intelligence.

"Globally, the European and American markets are already very mature in digitisation, but this is not the case in Southeast Asia - excluding Singapore - and there are more business opportunities," said Ice Kredit marketing director Zhou Yang. "After years of building our foundation in China, we would like to replicate our experience in Southeast Asia."

Among the ASEAN countries, Vietnam has been the biggest beneficiary of manufacturing lines shifting out of China.

China-plus-one

China-based companies - both homegrown and multinationals - have in recent years deployed a "China-plus-one" strategy for industrial chains, setting up manufacturing facilities in lower-wage Southeast Asian countries, to cut costs and to avoid hefty tariffs imposed by Europe and the US on exports from China.

Among the ASEAN countries, Vietnam has been the biggest beneficiary of manufacturing lines shifting out of China.

Figures from China's Ministry of Commerce show that trade between China and ASEAN rose 6.7% to US$684.6 billion in 2020. Vietnam was also China's biggest trading partner within the bloc.

But China is not the biggest foreign investor in ASEAN - yet. It is still behind the European Union, Japan, and the US.

Following the signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement between ASEAN and China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand last year, several observers and industry insiders expressed their optimism for Southeast Asia to become an even hotter destination for Chinese investments.

"The relationship between China and ASEAN is simpler; there is less political obstruction and that will draw more Chinese businesses to the region." - Tommy Xie, head of Greater China research, OCBC Bank

Li Mingjiang, associate professor at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, said that it was "only a matter of time" before China became the biggest source of foreign investment in Southeast Asia. He said that even without the signing of the RCEP, investment from China would still grow exponentially.

"The China-US trade war is causing MNCs in China and low-end domestic manufacturers to turn to Southeast Asia; the Belt and Road Initiative also promises to bring large-scale projects, both of which will boost investment in Southeast Asia."

Tommy Xie, head of Greater China research at OCBC Bank, pointed out that in addition to the RCEP and other external factors such as market forces, geopolitics are also proving favourable.

He said: "After the pandemic, relations between China and Europe and the US will become even more complicated, there's no way of going back to the way things were. The relationship between China and ASEAN is simpler; there is less political obstruction and that will draw more Chinese businesses to the region."

Chinese firms and Singapore's unique role

It is not all hunky dory for Chinese enterprises coming to this region, as they face challenges such as cultural differences and language issues.

The hiring of Chinese workers by Chinese firms can be highly contentious in some countries, due to misperceptions that they are taking over local jobs, according to Tham Siew Yean, visiting senior fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Research Institute in Singapore.

"Host economies would like to see increasing use of local labour but the speed of replacement with local workers depends on how fast the local workers can acquire the technical skills needed for these jobs," he said.

"That can take some time as Chinese supervisors speak in Mandarin, and manuals are in Mandarin and so local workers have to learn the language to be trained effectively."

In some parts of the region, Chinese investments in the real estate sector have also suffered as mainlanders who bought properties as second homes are now trying to sell them off, since they are unable to access their units due to travel curbs.

"Chinese regulators have also curbed outbound investments in real estate and hotels," added Dr Tham. "Chinese investments in, for example, the automotive sector have also suffered from the negative impact of Covid on auto sales in ASEAN."

Political upheaval is a risk as well. In February this year, the Myanmar military coup triggered anti-Chinese sentiments, and Chinese-funded companies in Myanmar were targeted.

Late last year, a subsidiary of Chinese mining firm Delong Nickle Industry was hit by violent worker protests, reportedly due to dissatisfaction over compensation and employment terms.

More recently, Indonesian President Joko Widodo launched a campaign to shun foreign goods, directed at the predatory pricing of imported goods sold on e-commerce platforms.

Although he did not name any countries, the local media had suggested that many of the goods in question came from China.

In the case of Singapore, recent investments by Chinese companies have largely come from the technology sector.

Last year, Tencent, Alibaba, ByteDance and iQiyi all announced that they were either expanding or setting up their regional headquarters here.

"These companies have chosen to grow their presence in Singapore in order to leverage our diverse talent and stable operating environment, as they seek to capitalise on the growth of Southeast Asia," said Economic Development Board executive vice-president Lim Kok Kiang.

Ice Kredit marketing director Zhou Yang said that Singapore has a stable political environment and financial system, and is also the most developed economy in ASEAN.

These factors, as well as policy transparency, make it an ideal base for growing the firm's presence in the region.

Singapore's position as a unique blend of East and West, and a nation that is "trusted by both China and the West" is its biggest strength, according to OCBC Bank head of Greater China research Tommy Xie.

A BBC report last year noted that setting up regional offices in Singapore had become strategic for Chinese enterprises amid tensions between the US and China.

The report quoted Nick Redfearn, deputy CEO of UK-based business consultancy Rouse, as saying that regional headquarters of Chinese companies, acting as foreign investors in other countries "can help Chinese companies avoid the appearance of Chinese investment".

To this, S Rajaratnam School of International Studies associate professor Li Mingjiang said there were indeed examples of Chinese companies using Singapore as a springboard to get around the US-China trade war.

"At the same time, [they are] hoping to use their Singapore offices to make investments without having to deal with negative perceptions of Chinese investment in the destination country."

Related: Why Southeast Asia has a love-hate relationship with China | How should Southeast Asian countries respond to an upsurge in Chinese investment | Southeast Asia a contested venue for telecommunication superpowers building 5G networks | Wake-up call for ASEAN countries: Curb over-reliance on China and seize opportunities of global supply chain restructuring