The stories behind the woodcuts

A friend sent me a woodcut by an anonymous artist showing an itinerant hawker sitting on a stool at his stall, with sticks of meat in his right hand and a fan in his left, grilling satay on a wooden charcoal stove. On either side of him are wooden boxes connected by a shoulder pole, on which are placed the satay gravy and the plates and other utensils. The subject matter and style place it as a work of times past.

There is really no way of telling how old it is. The interesting thing is, it is not cut on a piece of wood made for the purpose, but a drawing board meant for technical drawings, the kind with a gap on the side to stick in a T-rule.

Secondary schools in Singapore used to run technical design lessons, including compulsory classes in technical drawing, where students learned perspective, drawing 3D images by following three-plane projections. You could not do technical drawings without a drawing board and T-rule, along with a set square, to come up with accurate parallel lines. The school would have drawing boards, but you used your own T-rule; on days with technical class, students would have their T-rules in hand or in a long bag on their back, looking like swordsmen just coming down from some mountain.

According to the Singapore Infopedia website, from 1969, lower secondary students in Singapore - all the boys and half of the girls - had to take technical lessons, including technical drawing, metalwork, woodwork or electrical work. The other half of the girls took home economics classes. From 1972, 20% of upper secondary students went to technical classes.

In the late 1960s, Britain pulled its troops out of Singapore, and local unemployment grew. Singapore pushed hard for industrialisation, and there was demand for many blue-collar technicians and workers. Technical education was rolled out in secondary schools with the aim of nurturing students' interest in technical work.

Given that the woodcut was done on a drawing board, my guess is that it dates from the late 1970s. In the image, behind the satay seller is a stilt house, so the subject matter might be even older.

The stories of Singapore's history

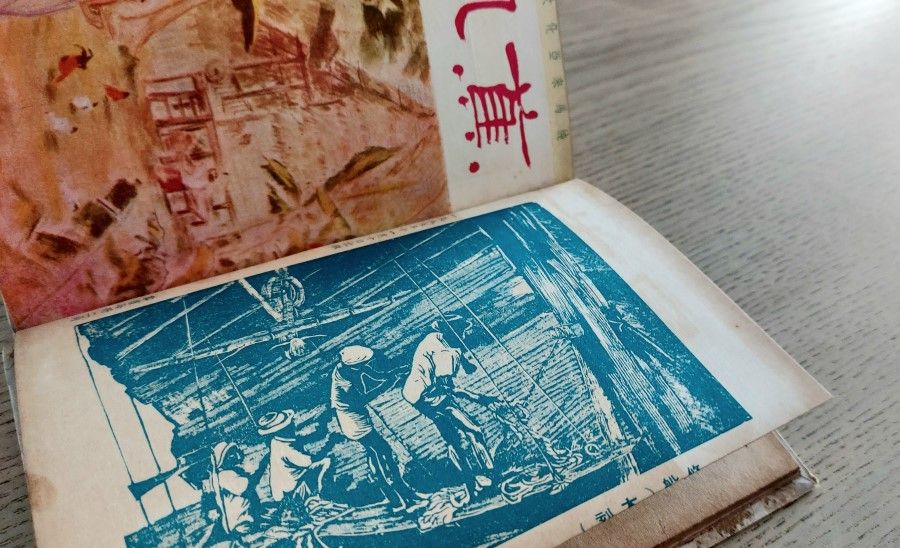

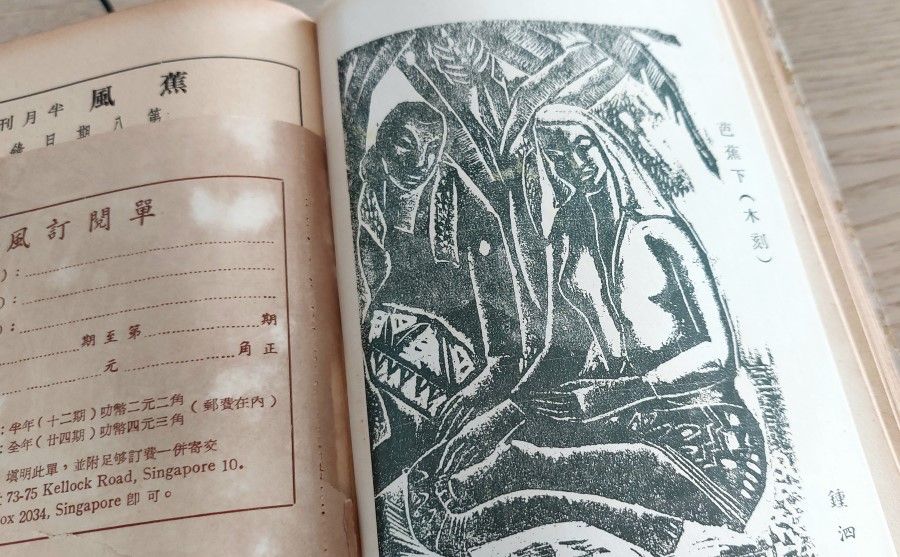

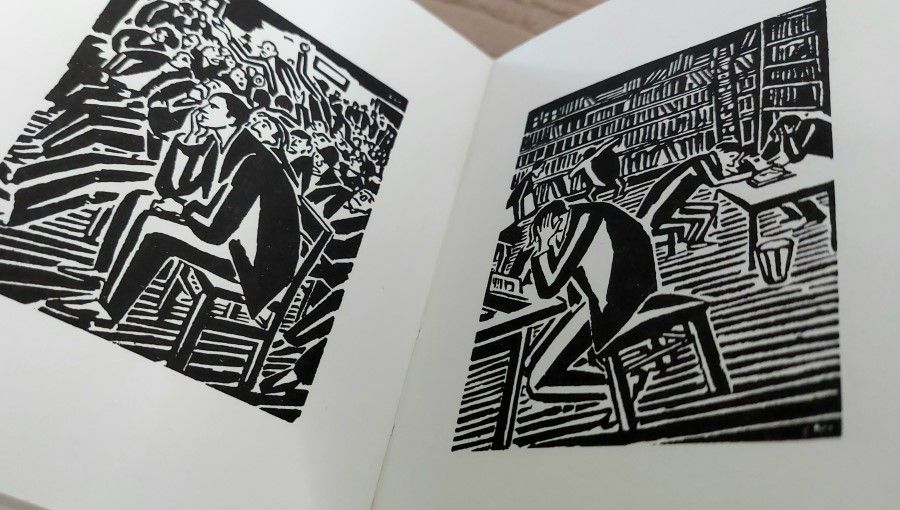

The first compilation of fortnightly literary periodical Chao Foon is a valuable old volume that collects the issues from its very first one in November 1955 to April 1956. I recall literary and culture magazines used to publish many art works, including woodcuts. The compilation features three woodcuts - Boat Repairs by Yan Jingnan in Issue 1, Waiting for the Show to Start by Jing Yun in Issue 4, and Under the Banana Leaves by Cheong Soo Pieng in Issue 8.

"The tongkangs were towed by tugboats, and holes were bored into the boats' holds to allow water to enter and sink them." - Thio Boon Chin, who repaired lighters as a young man

I found on the internet another woodcut by Yan Jingnan called The Return, depicting fishermen pulling little fishing boats up on shore on their return. His work Boat Repairs seems to depict the boats called lighters. A few years ago, I interviewed Mr Thio Boon Chin, who repaired lighters as a young man and remembered repairing them under the Merdeka Bridge in 1980.

Lighters were either twakows or tongkangs; twakows carried goods to the piers along the banks of the Singapore River, while the larger tongkangs required deep water and did not come into the SIngapore River but only transported goods in the sea around Singapore.

Mr Thio described the final fate of tongkangs: "After the era of the lighter industry came to a close, some tongkangs were towed to the open sea and sunk. My cousin handled over 100 boats; they were sunk off Pulau Semakau. The owners applied to the port authorities to go to more remote waters. The tongkangs were towed by tugboats, and holes were bored into the boats' holds to allow water to enter and sink them. This was tough and laborious work. Later on they used chainsaws, and the boats were sunk faster. This was in the late 1980s. As for how the twakows were destroyed, I don't know."

Speaking of lighters, one is reminded of the bustling scenes of the Singapore River full of lighters loading and unloading goods. The trade that they supported was once the lifeblood of Singapore's economy. Listening to Mr Thio speak of this chapter in history, I was stirred with emotion; the sinking of the lighters was the end of an era.

Strong connection to Lu Xun

On the National Heritage Board website, there is a write-up in Chinese on local art, including something on a woodcut illustration called Waiting (等待) from 1953 by the late artist Tan Tee Chie. The write-up says woodcuts were once popular in Singapore, and can be traced back to China, especially the modern woodcut illustration movement led by literary giant Lu Xun in the 1930s. With Lu Xun's strong advocacy, artists in China and Chinese artists in Singapore began to be exposed to the illustrations of German Expressionist artist Käthe Kollwitz.

Flipping through a mimeographed songbook - Songs for the People 1974 (《1974年大众歌选》) - I find between the pages a woodcut bookmark, showing a half-body profile of Lu Xun. Another volume from 1970 - Short Stories of Combat (《战斗的散文》) - has a cover that also features an image of a woodcut: Lu Xun with his hand raised, as if guiding the way, against a background of rows of young students moving forward.

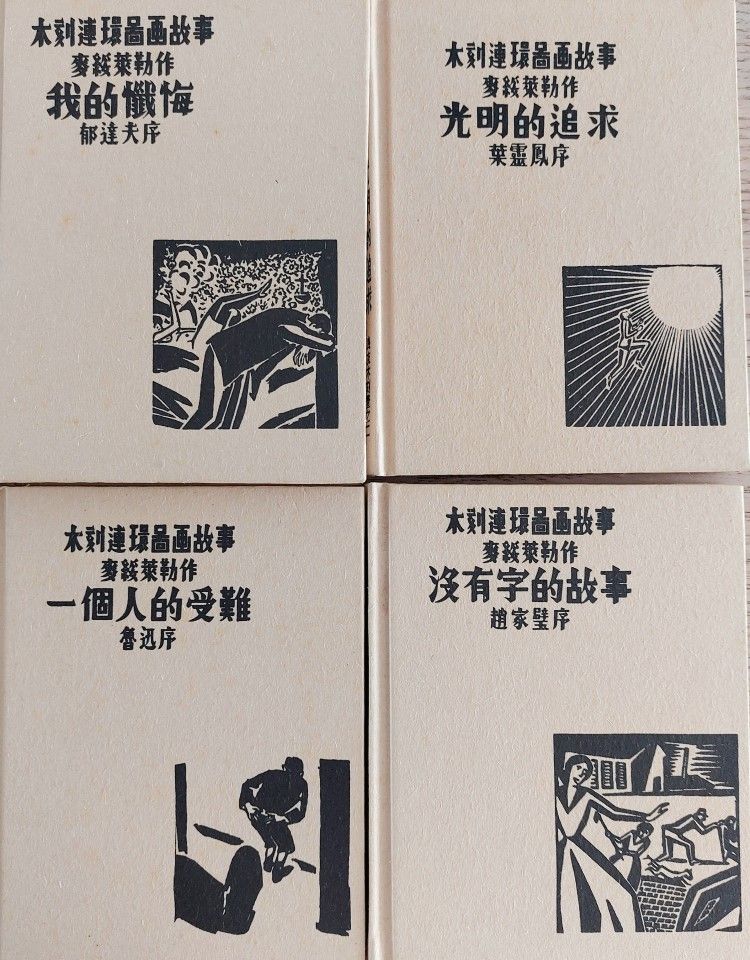

Masereel's various series of woodcuts were collected into four volumes, each of which told a story almost in comic form - the precursor of the modern graphic novel in China.

The book also includes a write-up of La passion d'un homme (lit. The Passion of a Man or Man's Suffering), a woodcut novel by Belgian artist Frans Masereel. This also has links to Lu Xun. In 1933, Liangyou Book Company in Shanghai published four of Masereel's woodcut novels, with forewords by Lu Xun, Yu Dafu, Yeh Ling-feng and Zhao Jiabi. Lu Xun wrote the foreword for Man's Suffering.

Masereel's various series of woodcuts were collected into four volumes, each of which told a story almost in comic form - the precursor of the modern graphic novel in China. Yeh Ling-feng recalled: "In the summer of 1933, I bought a few volumes of Masereel's woodcuts in a German bookstore in Shanghai. Zhao Jiabi of Liangyou Book Company saw it and wanted to reproduce them, and took them to seek the views of Mr Lu Xun. Mr Lu was open to this and also agreed to write a foreword, and so the work proceeded."

Interestingly, Yeh said that after the new edition was published, Zhao did not return the original German edition, as he said all the volumes had been taken apart during the printing process. "While he did recompense me for the cost of the volumes, they were no longer available, and so I lost those four volumes. Fortunately, there was the new edition, which was quite well produced, and so I had nothing more to say."

That little book from 1933 is long out of print, but in 2006 a Chinese publisher managed to come up with an edition that was a reproduction of the original volumes, so that people could admire them again. Speaking of that set of books, I recall the good times I had walking around Page One bookstore - I spotted the volumes at Page One in Vivocity.

Related: Challenges of Singapore's Chinese community amid competing influences: Lessons from an old bookstore | True gems: Singapore's pioneers of the arts deserve more credit | What old Chinese textbooks say about life and times in Singapore | How the Shanghai Book Company enlivened Singapore's cultural scene | Chinese bookshops in Singapore: Art salons of the 1970s and 1980s | Large steamed meat buns: A flavourful memory of old Singapore | What is Nanyang art?