Taiwanese art historian: What my father taught me

My father's name was Jiang Shu (蔣樞), courtesy name Keming (克明).

The date of birth on his identification card reads that he was born in the second year of the Republic of China (1913), on 17 December according to the Chinese calendar.

But from its own telling of it, he was actually born in the second year prior to the founding of the Republic of China. That would mean that he was born in 1910, the Year of the Dog.

Father's hometown of Sanxicun (三溪村, lit. three streams village) is in Changle District, Fujian province. I am not familiar with Sanxicun and have only been there once. When I was there in 2003, I had the impression that it was just a short distance from the newly-built airport in Changle District. But as soon as I arrived in Sanxicun, I found myself standing before a quaint old village. There were the Pingshan mountains, which were not tall but picturesque; there were old bridges, stone embankments and flowing streams that dotted the landscape. It is said that this is where the three streams of Tongxi (潼溪), Beixi (北溪), and Nanxi (南溪) meet, hence the name "Sanxi".

Father rarely spoke about his hometown. I only knew that our ancestors mainly farmed for a living, and used to own a timber mill, operating a boat charter transporting timber to and from Minjiang Kou (闽江口).

I went to Sanxicun to pay my respects at the ancestral graves. Although it was already the 21st century, the village seemed frozen in time. A few houses bounded the village square where the young and old gathered to play or chat. Life was quiet and slow, as if in the days of the Tang or Song dynasties.

The ancestral house that Father used to live in was still standing; it was a low-rise stone-built dwelling that was simple and spartan.

Local relatives brought me to a small, dark room. The walls were thick and the windows were small. The space could only fit a bed and a table. They told me that this was Father's room.

On the way to the ancestral graves, we walked on a path through fields, kicking up clouds of yellow dirt as we went. A few distant relatives and some of the younger ones came along; some walked ahead while others trailed behind.

The ancestral graves were sited at the foot of Pingshan, in one large burial mound. A headstone stood before me with the names of a dozen uncles and other relatives engraved on it. I knelt down and bowed. Our blood ties ran deep but we were not fated to meet in this life. I prayed that the souls of this universe and every being in the heavens and the earth would be blessed with a good reincarnation.

Separated by the Taiwan Strait, he lost all contact with his loved ones.

Father rarely talked about his hometown, mainly because he left the village when he was very young.

He was 14 then, he said, when he left to join the army amid chaos and war, and took part in fighting all over the country. He only returned to his hometown after 1949, and lived a reclusive life for two years there, married with four children. After numerous twists and turns, he uprooted his family and left for Taiwan via the Matsu Islands. From then on, Father was no longer fated to return to his hometown.

Separated by the Taiwan Strait, he lost all contact with his loved ones. Based on my rough estimate, he only stayed in his hometown for ten over years. Similar to many other people in times of war, he wandered from place to place and had little physical contact with his hometown.

A love of reading

When he was a child, Father studied at an old-style private school in the village for a few years. He loved to read. Incidentally, Sanxicun was known for its rich literary culture in the Song dynasty. At one point, it even produced two jinshi (进士, imperial scholars) at one time. These achievements are talked about in the village until today and have perhaps greatly inspired the youths living in rural Sanxicun.

But for families that farm and do business for a living, studying was purely for the sake of gaining financial literacy, and not in preparation for a career in officialdom. After studying for a few years and gaining basic literacy skills, they would have to work in the fields or learn to make a living in a timber mill. Driven by his desire to continue studying, Father left home without saying a proper goodbye, and sought out a living by himself.

If it was as Father said, and he had left home at the age of 14, then that would have been around the year 1924.

Entering the military full of high ideals

Without going into the details, Father said that he was wondering about and had reached Guangdong from Fujian, where he got terribly ill as his body could not adapt to the local environment. Fortunately, a good Samaritan took him in and nursed him back to health. Upon his recovery, he heard that the Whampoa Military Academy had established a branch in Guangxi's Nanning. So, he headed to Nanning in the hope of entering military school.

I did some research and found that the Nanning branch was established in the spring of 1926. There was a "student section" that enrolled secondary school students who would be trained for 18 months before getting deployed to the Northern Expedition.

If Father had left home when he was 14, travelled across the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, and spent two years constantly wandering about, poor and destitute, that must also have been the most vibrant time of his life as an aspiring youth.

I did a rough calculation: Father would have been 16 when he enrolled in the Nanning branch of the Whampoa Military Academy.

Sun Yat-sen founded the Whampoa Military Academy with high hopes and great faith. A line in the school song goes: "Fight a bloody path / Lead our oppressed people / March forward..." A school founded on these goals was indeed enticing to youths with great ideals, and also granted Father's wish to continue studying.

On one occasion, Father revealed that when he first applied to the military school in Nanning, he was not yet of age but had insisted on staying put. So, he ran errands for the school until he could be officially enrolled. This meant that the exact year when Father arrived in Nanning was roughly between 1926 and 1927.

Perhaps it was because he dearly cherished the hard-earned opportunity to go to school, Father - who was never boastful or flamboyant - would occasionally talk about how hard he studied and how diligently he trained, and how he was often chosen as the model student by his trainers.

Father chose the path himself and had no family to fall back on. He did not have any social resources and carved out a way all by himself. I guess Father must have once been very proud of himself!

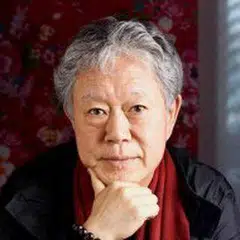

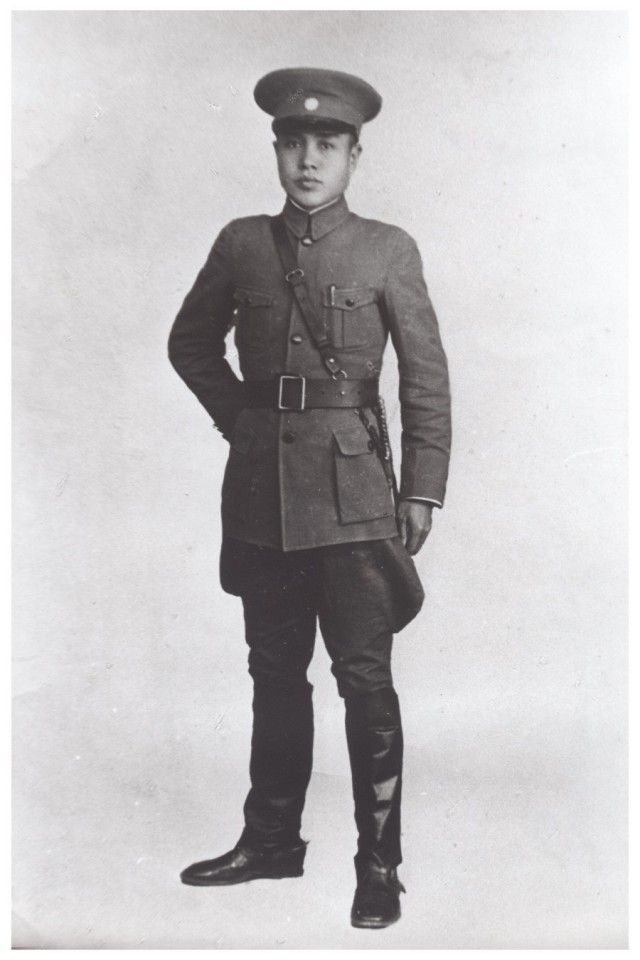

A photo of Father sits on my desk. There he is in full military uniform, with a large army cap on his head, knee-high riding boots, and a firearm belt strapped across his chest. On the back of the photograph, Father neatly wrote: Autumn, 25th year of the Republic of China, Xi'an army headquarters, 26 years old.

His standard was too high for me; he was at a level I knew I would never reach. I respected him but I also feared him. Naturally, there was a distance between me and Father as a result.

Frugal and disciplined

Perhaps it was his difficult childhood that had taught him to be extremely diligent and frugal. Chinese philosopher Zhu Xi's (honorific title Zhu Zi) maxim for family management was always hung up on our living room wall. It read: "Forget not the amount of hard work that went into growing each grain of rice we eat. Think about the amount of blood, sweat, and tears that went into producing every single spool thread we wear." The inspirational quotes from Father's teachings that were somewhat boring and rigid to us were what Father lived by his entire life. He practised what he preached without compromising his principles for a single moment.

Father truly "woke up at daybreak" every single day and proceeded to "wash and sweep the yard" after that. Hardly a day goes by without him doing that.

Something else left a very deep impression on me: Father would occasionally sleep on a wooden bench that was only roughly 30cm wide. He would not turn or sleep on his side. Neither would he fall off the bench.

I was close to Mother when I was a child, probably because I felt that Father was too disciplined and meticulous, like someone who made no mistakes. I stood in awe of him, as he made me realise how lazy and ill-disciplined I was. His standard was too high for me; he was at a level I knew I would never reach. I respected him but I also feared him. Naturally, there was a distance between me and Father as a result.

In my memory, Father never threw anything away easily. In the 1950s and 1960s, a time where there was a lack of economic and material things, Father used to coach us as we did our homework. He would use pieces of paper that already had pencil marks on them for ink pen calligraphy. After that, he would keep the ink-stained paper and use them to practise ink brush calligraphy. He kept every piece of paper that I would otherwise have thrown away because he thought that they were still useful. He folded them into neat stacks and kept them away. Back then, we still used wood or coal for cooking, and these paper would also be used to start a fire.

As far as I can remember, there was hardly any "rubbish" around the house for nearly two decades.

Nothing is ever 'trash'

"Rubbish" is useless stuff. But to Father, I guess nothing should be seen as "trash"! He would always cut the buttons off torn and tattered clothes, keep them in a bottle, and take them out whenever Mother sewed new clothes for us. There was also literally nothing left over from each meal we had. Pineapple and sugarcane peels, as well as banana and lemon peels, would all be used as fertilisers in our vegetable garden.

He liked to cycle and walk, and was still very fit in his old age. He built all of our fences at home by hand, splitting bamboo and weaving them together. He frequently climbed to the rooftop to repair leaks and replace tiles. He did everything himself and rarely asked for help.

There have been numerous calls to protect the environment in recent years. Recycling materials and not polluting the environment have become new values to live by. But for Father, these were not values but simply an attitude to life cultivated from a life of material deprivation which taught him never to throw anything away easily. I guess cherishing things and being diligent and frugal are also the very beliefs that have been passed down from generation to generation in Sanxicun.

Nearing the 1970s, Taiwan's consumer economy changed. Large-scale manufacturing and production stimulated consumption, and material waste became more apparent. Times have changed and so have general trends. Father's traditional attitude towards material things once clashed with my perceptions. In an era where consumption and novelty were encouraged, he was still keeping all sorts of "rubbish". Bottles, cans, old newspapers... He even kept dried-out ballpoint pens by bundling them together with a rubber band, and neatly tucked them away in the corner of a drawer.

And as for countless pairs of leather shoes that the children have already grown out of, he would periodically take them out to polish them before putting each pair away again.

As the economy prospered, people started replacing material things quicker than ever before. They sought to replace things even before they were spoilt, and so the old things became "trash".

We were already cooking with gas, but stacks of "waste paper" were still piled up in the corner of our house.

I think that our house was always filled with "rubbish" that Father had sorted out and neatly put aside.

"Why can't we throw away the things that can't be used anymore...?" I questioned.

"Why throw them away?" He still couldn't understand.

"Those ballpoint pens. You can't even use them to write anymore. Why still bother to keep and bundle them up in the drawer?"

I opened the drawer for him to take a look at - I guess he must have felt very wronged. Even until the day he passed away, perhaps he still wondered why people could throw things away so easily.

He would carefully squeeze our shared toothpaste section by section, not wanting to throw it away before the tube was used up. And as for countless pairs of leather shoes that the children have already grown out of, he would periodically take them out to polish them before putting each pair away again. Those were shoes that we would never wear again, but he did not see them as "trash".

An environmentalist by default

Perhaps the generation of youngsters who grew up in peacetime and have no lack of material resources like me would think that Father's frugality is an outdated form of stinginess?

But it is also after Father passed away and after we entered the 21st century that we witnessed enormous changes in Mother Nature: air pollution, the global threat of PM2.5 (minute particle pollution), and the increasing proportion of respiratory cancers; marine pollution, destruction of water resources, and microplastics in drinking water; car emissions and global warming, melting of the polar ice caps, sudden temperature changes, large numbers of creatures on the brink of extinction, ecological imbalance and so on.

Under such drastic changes, what is humanity's next step? How will mankind's attitude towards life and material things change? Do we still have time to do a final deep and sincere reflection?

The beliefs that my Father's generation had upheld have been completely annihilated in the consumption-driven market economy. My generation once questioned Father's humble attitude towards material things. My generation once scorned his backwardness and conservative mindset. But it is also my generation that has - in a short span of 50 years following WWII - consumed large volumes of resources, polluted the environment, and brought about great catastrophe to ecology so quickly.

I want to quietly reflect before Father's "maxim for family management" - "each grain of rice" and "every single spool of thread" - have I ever cherished all the blessings that I have in the palm of my hands?

2020, Geng Zi Year of the Rat, Father's 110th birth anniversary. The raging Covid-19 pandemic has claimed nearly two million lives and infected tens of millions of people. The coronavirus is still spreading, but technology - the very thing that humans are so proud of - stands helpless in the face of it. Are catastrophes Nature's timely warnings? Under such drastic changes, what is humanity's next step? How will mankind's attitude towards life and material things change? Do we still have time to do a final deep and sincere reflection?

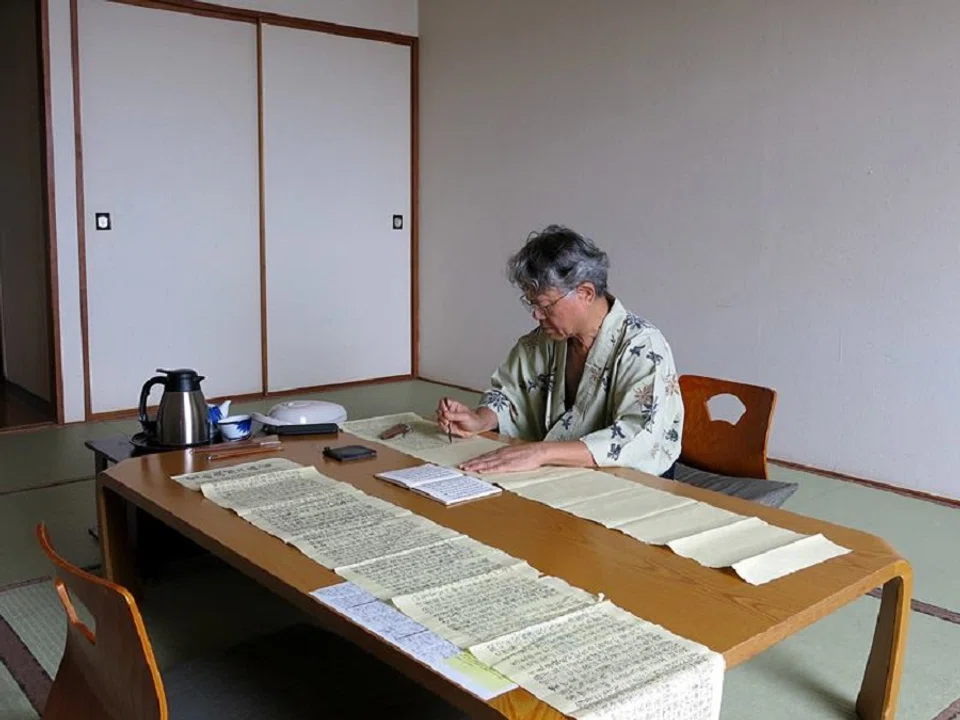

I am reminded of Sanxicun where Father was born, and of his deep desire to study when he was young. Coincidentally, I had a sum of royalties in the mainland that I could use and got to know that Sanxi Elementary School was raising funds to build a library. That along with some help from my friends in the publishing industry and my niece's contacts, I am happy to hear that the library construction is nearing completion. This was also done in memory of my Father, as a way of thanking him for the many unspoken teachings he has left me, and for letting me re-evaluate my attitude towards life.

The royalties came from avid readers. In Father's hometown, there will be a library where the future generations can gather to learn and think. I believe this is what Father, as well as avid readers, would have loved to see!

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as "父親".

Related: Taiwanese art historian: My mother waited for her soldier husband to return from war, just like Wang Baochuan | Taiwanese art historian: How should I meet my mother in the afterlife - as a child, an adult or an old man? | Picking up an ink brush amid the pandemic, what do I write? | A eulogy, intimate memories and a flawed piece of calligraphy