Shenzhen: The city that built China’s tech empire

With China intent on leading global technology, Shenzhen has emerged as its foremost hub of innovation. Researcher Chen Xiangming and entrepreneur Taylor Ogan explore how this powerhouse of hardware, talent, and spinout startups is propelling China’s tech ambitions — and reshaping the US–China innovation rivalry.

“Rome wasn’t built in a day, but Shenzhen was built as an almost ‘instant city’”. A small fishing town on China’s southern periphery bordering Hong Kong with fewer than 100,000 residents before 1980, Shenzhen stands as a global megacity of around 20 million people today. Its GDP soared from 270 million RMB (around US$38 million) to 3.6 trillion RMB, a rise of 13,000-fold. While 45 years is not a short time span, they compress a demographic, economic, and building explosion unprecedented in the long history of cities.

Back in 2016-17, we presented Shenzhen’s “instant-city” dynamic, massive in-migration, small and purposeful local government, and the Hong Kong nexus, as the scaffolding for today’s spinout waves of global technological innovation. This article revisits the dramatic transformation of Shenzhen.

Shenzhen now hosts 25,000 high- and new-tech companies — equivalent to 12 such firms per square kilometre...

Pathway to global innovation dominance

From its miraculous growth, Shenzhen has shot up to the pinnacle of technological innovation in China and the world. Starting out as a special economic zone for labour-intensive factories with zero high-tech activity, Shenzhen now hosts 25,000 high- and new-tech companies — equivalent to 12 such firms per square kilometre — making it China’s leading city in both the absolute number and average density of advanced technology enterprises.

In 2024, Shenzhen filed 16,300 international patents, leading all Chinese cities for 21 consecutive years. Of those patents, Shenzhen-based Huawei alone accounted for 6,600 or 40%, leading all global companies seven years in a row.

The sheer density and output of Shenzhen’s innovation ecosystem are unmatched globally. No city or region can claim a comparable concentration of high-tech firms, patent filings, and globally dominant companies emerging from such a compact area. To arrive at the apex of global tech innovation through a fertile ecosystem, Shenzhen has travelled at breakneck speed along a trailblazing pathway of pioneering China’s reform.

Local government as the reform driver

As China’s first special economic zone tasked with bold reforms not allowed elsewhere in 1979, Shenzhen started out with special first-mover advantages including low taxes for Hong Kong investors. But what mattered most was Shenzhen’s non-traditional government that experimented with audacious and purposeful reform policies — the most consequential of which was to disrupt the hukou system by providing large numbers of new migrants to Shenzhen with the same welfare benefits as for local residents.

Today, two-thirds of Shenzhen’s population call the city home without its local hukou, making it China’s largest city for migrant dwellers who have accepted the popular moniker of “once you come, you are a Shenzhener”.

This move, more than anything else, transformed Shenzhen into the most attractive destination for risk-takers from across China — some of whom, as Chen Xiangming documented in his late 1980s dissertation, left their secure and settled lives in Beijing to seek new opportunities.

Among these early risk-taking entrepreneurs were the legendary Ren Zhengfei, who founded Huawei in 1987, and Wang Chuanfu, who established BYD in 1995 — both in Shenzhen. Today, two-thirds of Shenzhen’s population call the city home without its local hukou, making it China’s largest city for migrant dwellers who have accepted the popular moniker of “once you come, you are a Shenzhener”. From 2020 to 2024, Shenzhen gained 429,000 permanent population via in-migration, leading all major Chinese cities. This massive migrant population in Shenzhen provides the human resource pool for productive economic activities.

Higher education, talent production and tech innovation

A top innovation hub, Shenzhen demands a top higher education system for producing advanced talents. In its earlier years, however, Shenzhen had little higher education. Shenzhen University, founded in 1983 as the city’s first local institution, only began significantly expanding its STEM graduate and undergraduate programs much later. The local college-educated labour pool remained shallow as Shenzhen was a traditional manufacturing centre.

Once it became clear in the 1990s that Shenzhen was going to move beyond a “factory town”, the Shenzhen government proactively set out to build a complete innovation chain by attracting the best universities in the country.

In 1996, it launched the Research Institute of Tsinghua University in Shenzhen (RITS) with Tsinghua University, the “MIT of China”. Tsinghua University and Peking University — known as the “Harvard of China” — established graduate schools in Shenzhen in 2000 and in 2001, respectively.

In 2011, Shenzhen launched the Southern University of Science and Technology, which has since become a top contender for the world’s top 100 universities. In 2014, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), one of the top-ranked universities in Asia and the world, opened a comprehensive campus in Shenzhen, further enriching the city’s higher education landscape.

As Shenzhen gains innovation power, it has become more integrated with neighbouring Hong Kong and nearby Guangzhou to form a regional innovation ecosystem...

More recently, Shenzhen has encouraged these excellent universities to commercialise their research, and partner with industries to incubate high-tech startups. RITS has spun off over 3,000 small tech startups across various industries. Through university-industry partnerships and beyond, Shenzhen has established 21 national STEM labs and four provincial ones. These initiatives have propelled Shenzhen to rank just behind Beijing and Shanghai in talent attraction for the past four years, and it has been the top city in China for recruiting post-95 talent for two consecutive years.

As Shenzhen gains innovation power, it has become more integrated with neighbouring Hong Kong and nearby Guangzhou to form a regional innovation ecosystem, facilitated by the increased ease and speed of physical movement and talent flows across a highly efficient regional transport system.

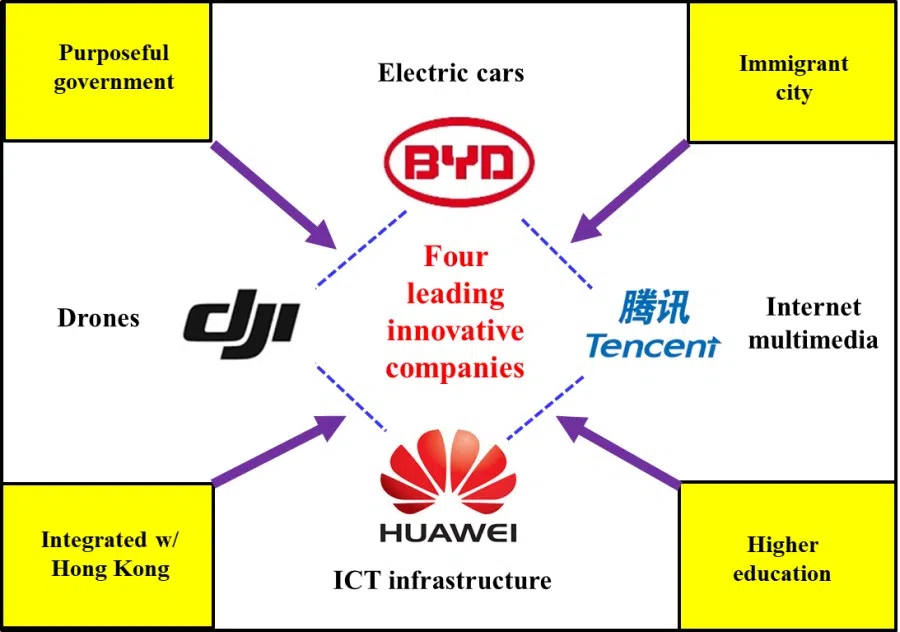

The opening of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou) marked a milestone of this three-city integration. It is not coincidental that Frank Wang, the CEO of DJI, founded his company in 2006 on the Shenzhen side of the border from his dorm at HKUST. This would not have happened without the Hong Kong-Shenzhen nexus (see Figure 1 above).

In 2025, the three cities collectively ranked No. 1 among the world's top 10 most innovative city-regional clusters. This was based on an average across three indices, reflecting their percentage of the global total.

“Spinout City”: one large, interlinked innovation network

Looking at Shenzhen from the ground up, we see a “Spinout City” embedded in dense startup genealogies. Anchor firms like DJI, Huawei, and BYD, along with university-linked incubators and a dense parts ecosystem, create an “alumni flywheel” that turns technical managers into founders and component suppliers into platform companies. This cycle has driven successive waves of innovation in drones, portable energy, robotics, and now embodied-AI startups.

...the city’s legacy of shanzhai (copycat manufacturing) has fostered a pragmatic attitude toward IP and an open sharing of designs that, while controversial, accelerated bottom-up innovation.

Several distinctive conditions in Shenzhen enable this sustained spinout dynamic. First is the sheer density of skilled talent and embedded industrial know-how. With tech giants and their suppliers concentrated in one city, engineers can readily find collaborators, mentorship, and early customers when they strike out on their own.

The local supply-chain flexibility in Shenzhen allows hardware startups to prototype and iterate at an incredibly fast pace. Shenzhen’s long-standing network of component markets, contract manufacturers, and “makers” allows even small teams to turn ideas into products in months, not years.

In fact, the city’s legacy of shanzhai (copycat manufacturing) has fostered a pragmatic attitude toward IP and an open sharing of designs that, while controversial, accelerated bottom-up innovation. By openly circulating reference designs and reusing modular gongban (公板) or public, open circuit boards, Shenzhen’s ecosystem historically lowered costs and drastically shortened prototyping cycles.

Over recent years, Shenzhen has doubled down on nurturing spinout entrepreneurs through new institutions and policies. The city tolerates and even encourages a level of experimentation difficult elsewhere – for example, permitting extensive autonomous vehicle road testing, providing grants for robotics R&D, and allowing drone delivery cabinets in dozens of parks. Just as crucial, a hybrid of academia and industry has taken root to train entrepreneurial talent.

A key figure is Professor Li Zexiang of HKUST, who mentored DJI’s founder and went on to establish the XbotPark incubator and InnoX Academy in the Shenzhen region. These programmes integrate hands-on engineering education with startup incubation, effectively guiding young innovators from classroom to company. Students “build real prototypes, source parts through Shenzhen’s vast supply chain, and launch startups before graduation,” Li notes.

The result: many top graduates who might have joined big firms are now choosing to found startups — “nine out of ten stay and start their own companies”, in Li’s experience. XbotPark’s portfolio alone has produced dozens of hardware startups with several already surpassing billion-RMB valuations in sectors like robotics, smart hardware, and industrial automation.

This incubator-driven model has effectively created “startup genealogies”: DJI emerged from Li’s lab; DJI alumni begot new companies; now those too are spawning successors.

This incubator-driven model has effectively created “startup genealogies”: DJI emerged from Li’s lab; DJI alumni begot new companies; now those too are spawning successors.

Even Huawei’s own approach has evolved to embrace the startup ecosystem – the firm opened an embodied AI center and is collaborating with Shenzhen robotics unicorns UBTech (humanoid robots) and Leju (social robots) rather than going it alone. Such collaboration blurs the line between corporate R&D, which accounts for 93% of Shenzhen’s total R&D ranking No. 1 among all Chinese cities, and startup innovation, making Shenzhen one large, interlinked innovation network.

Thanks to its innovative drone industry, Shenzhen has become the leading hub of low-altitude economy for China and the world, boasting 1,085 drone departing and receiving stations, 309 flying routes, over 1,000 companies making low-altitude unmanned flying vehicles, and accounting for 70% of the world’s consumer-drone market. The city allows flying drones to deliver fast meals, cold drinks, even life-saving AEDs to receiving stations, and will soon begin transporting people.

Innovating from both above and below

While the main sources of Shenzhen’s innovative prowess has not changed since we identified them back in 2017, they have only been augmented, especially since 2020 when the national government designated Shenzhen as the “comprehensive reform demonstration city with Chinese socialist characteristics”, which reinforced Shenzhen’s unique four-decade-plus status as China’s reform pioneer. This policy has recently spurred the Shenzhen government to further speed up the online processing and handling of corporate requests and talent recruitment.

Shenzhen’s unique urban-industrial conditions have institutionalised a culture of spinout innovation and shortened the distance from idea to product. High talent density, close-knit supplier networks, and a pragmatic tolerance for iterative design give corporate veterans both the inspiration and the means to launch. Critically, early capital now often comes from equally young operator-investors — alumni of Huawei/DJI/BYD/Tencent who know exactly what to fund because they built with these founders before.

The bottom-up corporate and entrepreneurial drive sustains Shenzhen’s technological innovation as a powerful urban DNA. It reinforces Shenzhen’s high-tech manufacturing, making it less vulnerable to US tariffs that put a greater pressure on Chinese cities depending on labour-intensive exports.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)