Where China stands in the nuclear medicine gold rush

China is racing to turn its vast state-backed investment and swelling domestic isotope supply into a global power in nuclear medicine — but its bold drive to lead the next wave of cancer diagnostics and therapies still faces deep structural bottlenecks.

(By Caixin journalist Wen Simin)

Often tucked in out-of-the way corners of Chinese hospitals, nuclear medicine departments have for much of their history been mysterious places where few knew exactly what they do there.

What exactly they do there, though, is quickly becoming one of the more technologically promising fields of medicine and active areas of investment in the global pharmaceutical industry.

China got a reminder of this on 5 November, when the National Medical Products Administration made headlines after granting approval to Novartis AG’s blockbuster radioligand therapy drug Pluvicto. The targeted radiopharmaceutical for prostate cancer was the first therapy of its kind approved in China. This new class of therapy, which uses miniscule amounts of radioactive isotopes to zero in on tumours with far more precision than traditional radiation therapy, has already demonstrated its potential. Pluvicto, along with another Novartis nuclear drug called Lutathera, generated over US$2.7 billion in sales last year.

The Swiss pharma giant’s multinational competitors have invested billions of dollars to build their own nuclear medicine pipelines. In December 2023, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. announced a US$4.1 billion deal to acquire RayzeBio Inc., paying a 100% premium for the company and the several products it has in development. In March 2024, AstraZeneca PLC said it would snap up Fusion Pharmaceuticals Inc. for up to US$2.4 billion. The following May, Eli Lilly & Co. signed a deal worth up to US$1.1 billion with Aktis Oncology Inc. to use the biotech firm’s proprietary drug discovery platform to develop novel radiopharmaceuticals.

China has a plan for this growing medical field. In 2021, eight government departments, including the China Atomic Energy Authority and the National Medical Products Administration, issued a blueprint for a complete radiopharmaceutical supply chain in the country. Investment capital soon followed, creating a wave of Chinese nuclear medicine startups. In five years from 2019 to 2024, the number of companies in China focusing on the field has grown from around 20 to nearly 100, said Du Jin, chief scientist at China National Nuclear Corp. (CNNC) and head of the science and technology committee at China Isotope & Radiation Corp. (CIRC). In addition, domestic pharmaceutical giants such as Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd. and Yunnan Baiyao Group Co. Ltd. also got into the field, hoping to grab a piece of a wide-open market.

China has made strides in nuclear medicine. Earlier this year, CNNC delivered its first shipment of the key isotope used in Pluvicto and Lutathera — lutetium-177 — to market. However, domestic companies have yet to create a blockbuster drug like Pluvicto. Although China’s nuclear medicine pipeline is rich with possibilities, the industry remains held back by issues such as rigid regulations, a shortage of talent, and a tendency to pursue targets that already have established treatments with a secure market position.

The challenges pose a risk to the investors who have already poured billions of RMB into the industry, which, according to Du, received more than 5 billion RMB (US$703.4 million) in funding this year alone. And more fundraising is on the way. Two Chinese startups, Beijing Sinotau International Pharmaceutical Technology Co. Ltd. and Yantai Lannacheng Biotechnology Co. Ltd., have filed for IPOs in Hong Kong this year, vying to become China’s first publicly traded nuclear medicine company.

Targeted radiopharmaceuticals have fewer side effects, he [director of a nuclear medicine department at a top Beijing hospital] said, describing RDCs as “a precision-guided miniature nuclear missile”.

A miniature nuke

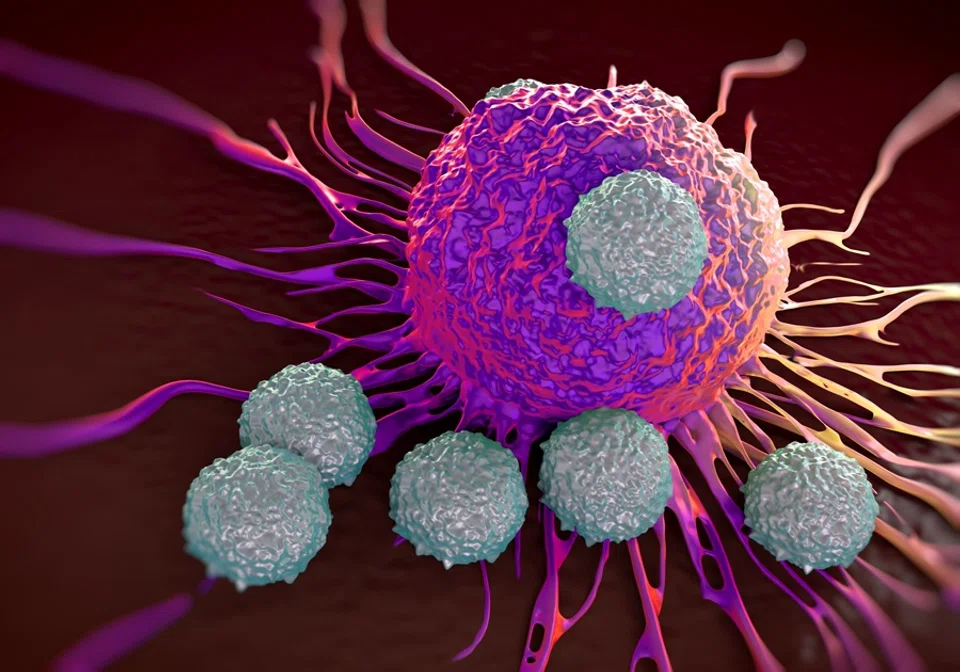

The excitement around Pluvicto and the broader field of radionuclide-drug conjugates (RDCs) stems from their fundamentally different approach to fighting cancer.

Traditional chemotherapy and many molecularly targeted drugs work by increasing the chemical toxicity in the body to disrupt cells’ metabolism, said the director of a nuclear medicine department at a top Beijing hospital. The problem is that their lack of precision often damages healthy tissue in the process of killing cancer cells.

Targeted radiopharmaceuticals have fewer side effects, he said, describing RDCs as “a precision-guided miniature nuclear missile”.

The drug comprises a targeting molecule that seeks out and binds to a specific protein on the surface of a cancer cell — in the case of Pluvicto, the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). Attached to this guide is a radioactive isotope that releases cell-killing radiation over a very limited range.

Once the targets are confirmed, a therapeutic is administered to destroy them.

For years, China was entirely dependent on imports for medical isotopes like lutetium-177. That changed in June, when China National Nuclear Corp’s Qinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Zhejiang province started shipping lutetium-177.

Currently, most of the approved nuclear medicine drugs in China are for diagnostic use, not therapeutic. Compared with blockbuster drugs like Pluvicto, it is a low-margin business.

Companies like the state-backed CIRC and publicly traded Yantai Dongcheng Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. primarily produce isotopes like technetium-99 and fluorine-18 for use in medical imaging. But these have very short half-lives — fluorine-18’s is just 110 minutes — requiring a national network of specialised “nuclear pharmacies” to produce and deliver them to hospitals in time. “This part of the market is relatively mature, but the profit margin is very limited,” one industry veteran told Caixin.

Still, nuclear medicine diagnosis overcomes some of the limitations of traditional biopsies. “A traditional pathological biopsy is like taking just one bite of a sandwich; you can’t know all the ingredients,” the hospital department director explained. “Nuclear imaging allows you to see the distribution of all the sandwich’s ingredients.”

A stable supply of domestic isotopes will allow companies to shift their focus from “seeking nuclides to seeking drugs”, taking some of the risk out of research and development (R&D) from a disruption in the isotope supply.

A breakthrough moment

For years, China was entirely dependent on imports for medical isotopes like lutetium-177.

That changed in June, when CNNC’s Qinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Zhejiang province started shipping lutetium-177. The isotope can be produced during normal power generation. This “two birds with one stone” approach makes it far cheaper to produce lutetium-177 at the power plant than at a dedicated research reactor, Du said.

“Thanks to the Qinshan Nuclear Power Plant, Novartis is expected to get the world’s cheapest lutetium-177 in China,” the industry veteran said.

This breakthrough marks a watershed moment for China’s nuclear medicine industry, said Chen Xiaoyuan, co-founder of Lannacheng Biotechnology, a spin-off from Dongcheng Pharmaceutical. A stable supply of domestic isotopes will allow companies to shift their focus from “seeking nuclides to seeking drugs”, taking some of the risk out of research and development (R&D) from a disruption in the isotope supply.

However, Du cautioned that the road to a commercial supply at scale will be a long one. The irradiated material must still undergo complex chemical separation and purification processes under strict pharmaceutical-grade standards, which has yet to be proven at a commercial scale in China.

The shortage of expertise is a sign that the most significant bottleneck is human.

A follower’s dilemma

Even with a domestic isotope supply, Chinese firms face an uphill battle in innovation. The vast majority of the nearly 100 companies in the field take a “fast-follower” approach, crowding around a few internationally validated targets like PSMA.

This creates a situation where it can be difficult to prove a new drug is better than what’s already on the market. “Due to the limited supply of Pluvicto, it is also difficult for R&D companies to obtain Pluvicto for comparative clinical trials,” the industry veteran said.

In addition, Novartis’s head start, brand and trove of clinical data create a “strong commercial barrier” that is hard for a copycat drug to overcome.

Breaking new ground by discovering novel targets for RDCs poses an even greater challenge, requiring deep underlying technical expertise that is still in short supply. “This also explains why the international giants choose to enter the nuclear drug field through mergers and acquisitions rather than internal R&D,” the industry veteran said.

A shortage of talent

The shortage of expertise is a sign that the most significant bottleneck is human. The explosive growth of the industry has created a severe talent shortage that touches every part of the value chain, from the research lab to the clinic.

“Those who understand nuclear physics do not understand drug manufacturing, and those who understand drug manufacturing do not understand the characteristics of nuclides,” the industry veteran lamented. “There is an extreme shortage of top-level, multidisciplinary R&D talent.”

Most professionals in the field come from niche disciplines like nuclear chemistry or medical engineering, which simply don’t have the numbers to meet the sudden demand, said Wu Xiaoyu, vice president of R&D at US-based Ionetix Corp.

This shortage extends directly into hospitals. The hospital department director recalled that in 2007, his entire nuclear medicine department consisted of just eight full-time employees and lacked advanced diagnostic equipment. Today, his team has grown to around 100 professionals, including doctors, nurses, chemists and physicists, making it one of the top departments in the country. But he emphasised that his hospital is an outlier and the industry as a whole still faces a talent shortage.

Without qualified staff and certified facilities, hospitals cannot offer nuclear medicine services. According to a 2024 survey by the Chinese Society of Nuclear Medicine, only 862 of the country’s top-tier hospitals have a nuclear medicine department, directly constraining the popularisation of the field in China.

Cui Xiaotian contributed to this story.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “In Depth: Where China Stands in the Nuclear Medicine Gold Rush”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.