China set to ease controls on genetic resources to plug biotech innovation gap

In response to criticism from the industry and scholars alike, China is set to loosen restrictions with regard to human genetic resources. How much of an impact would this have on the advancement of research in the biomedical field?

(By Caixin journalists Jiang Moting, Cui Xiaotian and Han Wei)

China is poised to relax its stringent decade-long regulations on human genetic resources in response to complaints from industry and academia that overly tough restrictions are choking innovation, particularly in the burgeoning biotech sector that is racing to create new medicines to treat everything from cancer to rare diseases.

The National Health Commission (NHC) is spearheading the reform, focusing on revising rules for the use and management of human genetic resources, sources told Caixin. The aim is to streamline administrative procedures, boost regulatory efficiency, and invigorate scientific research and the biopharmaceutical industry as a whole, the sources said.

Human genetic resources include genetic materials like organs, tissues, and cells containing substances such as the human genome and genes, along with related data and information. These resources are crucial for the research of new drugs and therapies that benefit public health and thus hold major economic value, while also being central to national biosecurity concerns.

Unshackling the research and development process is crucial if China isn’t to get left behind in the global race to create innovative new drugs and biotech applications, as well as bolster the treatment of rising incidences of diseases such as diabetes under the nation’s overburdened healthcare system.

China’s pharmaceutical market already lags far behind world leader North America, accounting for just 8.1% of global sales in 2022, compared to 52.3% for the US and Canada, according to a report last year by the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA). Perhaps even more telling, China’s expenditure on pharmaceutical R&D was 12 billion euros (US$13 billion) in 2021, compared with 69.7 billion euros in the US, according to the report.

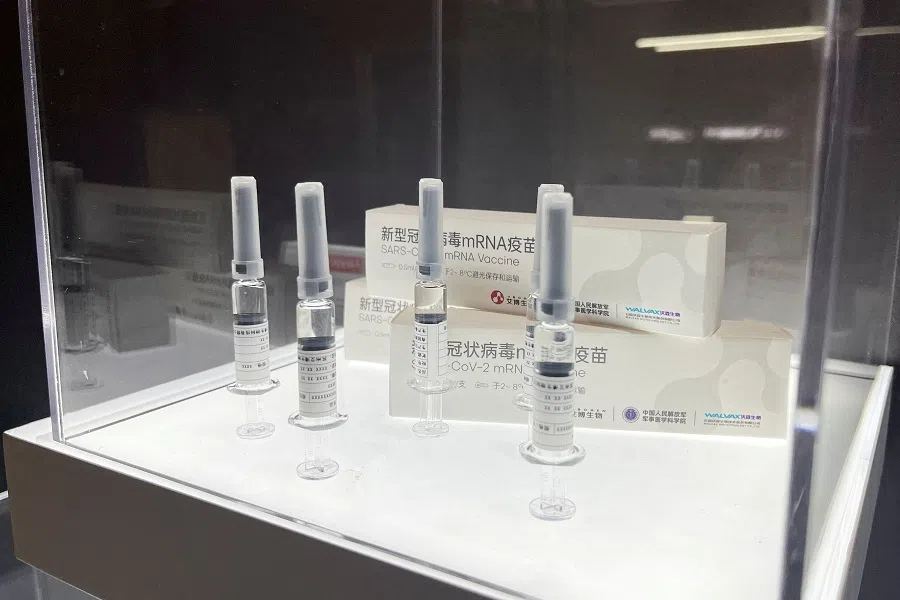

In terms of biologics, which are drugs or vaccines made from a living organism, China’s sector was estimated at up to US$6.2 billion in 2019, less than a tenth of the US$118 billion for the US market, according to a report that same year to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

Stringent regulations have become a headache, particularly for the innovative drug industry, in which players are in a perennial race against time to be first to get their drugs approved and onto the market.

“China is making good progress in improving its life sciences institutions and related academic talent pools, but the country has work to be on par with the world’s leading seats of biopharma research,” said Rahul Agarwal, Department of Business and Trade counsellor for Life Sciences & Healthcare at the British embassy in Beijing, in a February blog for the UK Bioindustry Association.

This estimate comes despite a predicted strong pace of growth. China’s innovative drug market size will grow from US$20 billion in 2022 to US$50 billion in 2028, wrote Agarwal.

In fact, despite the comparatively small level of spending on R&D, China has been working hard to close the gap, posting an annual growth rate between 2018 and 2022 of 15.6%, outstripping the US on 9.4% and Europe on 4.6%, according to the EFPIA report.

Long wait

Currently, the collection, preservation, transportation and utilisation of human biological materials in China require months-long approvals not required in most other countries and strict supervision under a regulatory framework established in 2015.

Stringent regulations have become a headache, particularly for the innovative drug industry, in which players are in a perennial race against time to be first to get their drugs approved and onto the market.

“New drugs have a life cycle,” said Chang Jianqing, vice-president of drug regulatory policy with Hangzhou Tigermed Consulting Co. Ltd. While the 20-year patent protection period may seem lengthy, it can be gradually eaten up by methodical preclinical and clinical research stages, and companies strive to expedite their drug development processes as much as possible, said Chang.

In addition to the extra time, the human genetic resource reviews also pose compliance challenges for businesses cooperating with overseas partners in areas such as data sharing. — a pharmaceutical executive

For a new drug to hit the market, it generally needs to complete three phases of clinical trials, with each requiring corresponding approvals.

In 2015, China initiated a reform of its previously cumbersome new drug review system, reducing the approval procedure to roughly three months, in line with approval times in Europe and the US This has fuelled a boom of the domestic biopharmaceutical industry.

But Chinese drug developers still face an additional review of human genetic resources. The extra time spent on regulatory reviews slows the pace of new drug research and development, widening the gap with other countries, said industry insiders.

In addition to the extra time, the human genetic resource reviews also pose compliance challenges for businesses cooperating with overseas partners in areas such as data sharing, a pharmaceutical executive said.

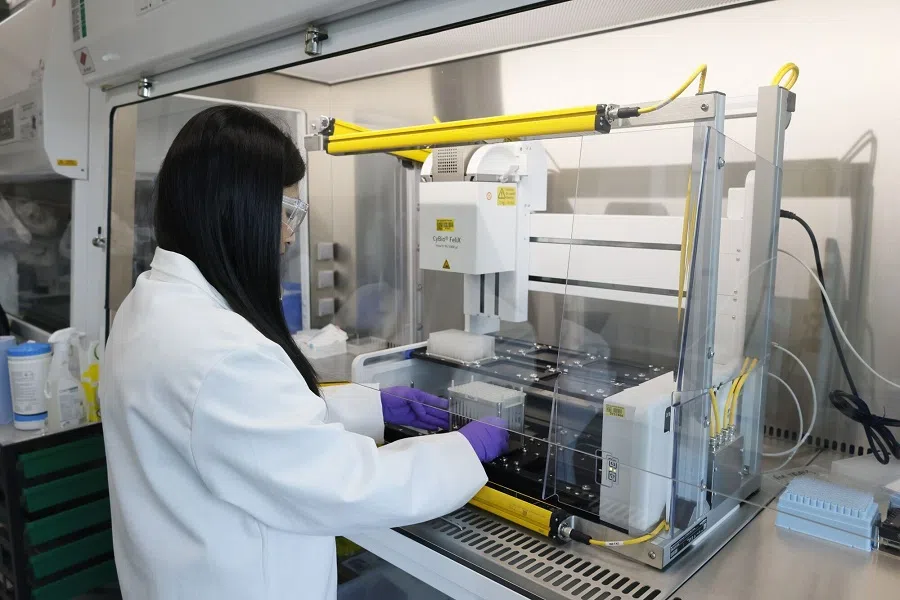

With global advancements in life sciences and biotechnology, international biomedical research has become increasingly data-intensive. But in China, the stringent regulatory control has hindered academia, industry, and researchers, who have called for reform. This has prompted regulators to shift towards easing restrictions in an attempt to balance biosecurity protection with industry development and innovation.

Indeed, over the past decade, China’s supervision of genetic resources has increasingly tightened, especially regarding data and material export and foreign partnerships. This results in about three additional months of administrative approval time for clinical trials compared to other countries and complicated reviews of international cooperation projects in genetic studies.

Innovative drug and gene therapy development are particularly affected, as their research involves genetic resources. Some foreign-trained scientists have hesitated to get involved in Chinese biotech startups due to regulatory concerns.

Industry experts have called for cautious interpretation of biosecurity concepts to avoid excessive regulation. They emphasise the need to balance supervision with the healthy development of scientific research and industrial activities to ensure China does not miss out on the next technological boom.

At the China Development Forum in March, AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot warned that excessive barriers to international cooperation, such as data exchange and utilisation of human genetic resources, would delay industry development.

“International cooperation is crucial for innovation,” he said.

Experiences in Western countries show that managing human genetic resources should feature openness, sharing, and development, said a senior geneticist who declined to be identified.

“These resources only have value when studied and transformed into scientific and industrial outcomes,” said the expert.

Relaxed control

China’s deregulation efforts began early last year when a government reorganisation plan unveiled during the National People’s Congress transferred supervision of human genetic resources from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) to the NHC. The NHC has since kicked off reform efforts to streamline administrative procedures, putting more emphasis on making use of genetic resources to benefit public health.

In July 2023, the 25-year-old Genetic Resources Office under the MOST was terminated. This had overseen gene-related aspects of scientific research and the biopharmaceutical industry, from sample collection to international cooperation and publication of research results.

In March 2024, the NHC officially took over supervision. Ahead of the handover, the commission between late 2023 and early 2024 held at least three intensive discussions with experts and industry representatives, forming a consensus on how to streamline administration and deregulate, Caixin has learnt. This included addressing institutional barriers in managing human genetic resources that hinder technological and industrial development, Caixin has learnt.

They agreed on the need to reduce regulatory overreach and imprecise risk control while maintaining the principle of “regulate where necessary, relax where possible.”

A primary focus of the reform is to revise the 2023 industry guidelines to further relax control. Officials and experts have discussed changes in three main areas, Caixin has learnt.

... they risk being classified as “foreign entities,” potentially prohibiting companies from collecting, preserving, or providing biological samples within China, or at least incurring substantial administrative costs.

First, experts suggested raising the threshold for projects subject to administrative approval for human genetic resource collection from 3,000 to 10,000 samples. This would ease the burden on innovative pharmaceutical companies and benefit domestic research projects by allowing research collecting less than 10,000 samples to avoid regulatory review.

The second revision under discussion is to clarify the definition of “foreign entities” that are subject to administrative review. Under the 2019 regulations, they are defined as foreign institutions established or under actual control of foreign organisations or individuals, but lacks a specific definition of “actual control”.

In the biopharmaceutical industry, the vagueness has had a significant impact as it is common for biotech startups to receive overseas investment, introduce new technologies and partners through equity swaps, and seek overseas listings.

Chinese scientists returning from abroad and former senior executives of multinational pharmaceutical companies are also key players in China’s innovative drug industry.

However, in these situations they risk being classified as “foreign entities,” potentially prohibiting companies from collecting, preserving, or providing biological samples within China, or at least incurring substantial administrative costs.

A founder of a gene therapy company told Caixin that such risks have hindered foreign investment and forced some business founders to resort to holding shares through others or setting up variable interest entity (VIE) structures, exposing the company to compliance risks.

The third area are changes being discussed including revising overlapping and contradictory regulatory provisions and optimising the overall application process for enterprises and research institutions.

This issue improved with the introduction of the 2023 guidelines, which state that entities in which foreign organisations or individuals hold less than 50% of the shares and do not significantly influence decision-making and internal management will no longer be classified as “foreign entities”.

In recent discussions, some experts proposed the definition be further relaxed. They suggested that medical, research, and other institutions established in the Chinese mainland by entities from Hong Kong and Macao should also be defined as Chinese entities.

If adopted, along with other favourable policies for the biopharmaceutical sector in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, this could significantly enhance the attractiveness of Hong Kong and Macao to foreign investment.

“The signal for reform needs to be clearly conveyed to genuinely reduce the burden on scientists and entrepreneurs, encouraging them to think boldly and act confidently,” said Wang Jing, an associate law professor at Beijing Normal University.

The third area are changes being discussed including revising overlapping and contradictory regulatory provisions and optimising the overall application process for enterprises and research institutions, Caixin learnt.

“The overall goal of the revisions is to make regulation more precise, efficient, and scientific. Once implemented, this will be a significant benefit for the industry, academia, and research sectors,” an expert who attended the discussions told Caixin.

But revisions to the guidelines can only be made within the framework of the 2019 Regulations on the Management of Human Genetic Resources, which established the main legal framework, and the Biosecurity Law, promulgated in 2020 to serve as the sector’s overarching convention.

More significant changes to the supervisory approach and fundamental revamp of administration will require deeper discussions and more substantial legal reforms, experts said.

Long road

It has been a decade-long road. China began building its genetic resources regulatory regime in 2015, led by the MOST. Before that, fledgling human biological studies were regulated by an interim measure issued in 1998.

In June 2023, a set of guidelines were issued to clarify and detail the 2019 regulations, reducing some strict requirements.

The 2023 guidelines incorporated industry feedback and made several optimisations and refinements to ease requirements in human genetic resource reviews. The changes have reduced the workload for such reviews by at least 40% at Tigermed, said Chang.

Although it still takes about one to two months to complete the human genetic resource reviews under the 2023 guidelines, “it is already much faster than before,” said Wang Lai, a senior vice-president of leading innovative drug developer BeiGene Ltd.

And it’s not just companies feeling the pinch of regulatory constraints, academic research institutions are also being hamstrung. Since 2019, any research involving human genetic resources must be registered with regulators for international cooperation before being publicly published.

“Only through utilisation can scientific research outcomes be transformed into international competitiveness in science and industry.” — a senior geneticist

But there has been a lack of precise definition of “research involving human genetic resources,” and authorities tend to adopt the most prudent and stringent standards, posing uncertainties in regulatory reviews. “Protection must be based on development, utilisation, and exploitation, rather than mere preservation without use,” said a senior geneticist. “Only through utilisation can scientific research outcomes be transformed into international competitiveness in science and industry.”

For instance, current rules stipulate that any cross-border sharing of human genetic information that may affect public health, national security, or public interests in China must undergo a security review. However, authorities have yet to issue documents specifying the procedures and criteria of such reviews.

In practice, many companies need to provide or allow access to human genetic data overseas. However, uncertainty about triggering a security review makes it difficult to anticipate project timelines, creating challenges for businesses, said Gu Yang, a lawyer at Han Kun Law Offices in Beijing.

Data sharing

Domestic data sharing is also a concern. In the digital economy era, human genetic resources are crucial, but China faces severe “data islands” between institutions, leading to low levels of sharing, said Ye Kai, head of the Interdisciplinary Research Centre for Informatics and Biomedical Sciences at Xi’an Jiaotong University.

“The genomic, phenotypic, clinical, and imaging data of the same person need to be combined to create value,” Ye said. “If this information is fragmented and doesn’t flow, the drivers of the digital economy are lost.”

Experiences in developed countries like UK and the US have indicated a clear path for human genetic resources management, which combines robust government regulations and national research institutions, according to Zhao Guoping, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and a microbiology expert at Fudan University.

“The government is advancing step by step with its laws and regulations. It’s now crucial to establish a unified, authoritative data platform, engaging in long-term data integration,” said Zhao. “This will enable data sharing and utilisation for public interests.”

It’s not just China’s government and industry grappling with the mechanics and implications of managing human genetic resources. Governments globally are also adjusting related policies, with regulation influenced by complex geopolitical, economic, technological, and industrial factors.

In an unprecedented move, US President Joe Biden recently signed an executive order to prevent certain nations, including China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Cuba, Venezuela, from accessing sensitive American personal and government data, including human genome and health data.

Countries like Mexico, Thailand, India, and South Africa have also been actively creating regulations to oversee and protect their human genetic resources, according to Yu Jiajia, an associate law professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

“Balancing security with efficient use of biomedical big data to promote social progress and economic development is a global challenge,” said Zhao.

Against the backdrop of global competition, it is necessary to assess human genetic resource development from a national interest perspective for better control. But sufficient freedom should be left for exploratory and fundamental research, said the senior geneticist.

China isn’t historically averse to openness in this field. Indeed, in 1999, China proactively embraced international collaboration in human genetic research, joining the Human Genome Project and allocating government funding to support Chinese scientists in sequencing tasks.

In 2002, China took part in the inaugural meeting of the International HapMap Project with several other countries including the US and UK, establishing a free, open database of genes related to human diseases and drug responses.

And in 2008, China became a key participant in the 1000 Genomes Project, contributing samples to the international research effort to establish a detailed catalogue of human genetic variation. The results were made available to researchers worldwide.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: China Set to Ease Controls on Genetic Resources to Plug Biotech Innovation Gap”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)