Tropical pursuits: Collecting ink paintings in Singapore

CEO of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre Low Sze Wee traces the history of Singapore's ink art collecting trends, and the bonds of friendship forged between Chinese and Singaporean artists.

When Chinese artist Xu Beihong passed through Singapore in the 1920s, he recalled that the island was like "hot wasteland with hardly any art to speak of". But was this an accurate characterisation of Singapore's cultural scene then? Were there really no artists or art collectors in those early days?

Early beginnings

Recent research has revealed that the presence of art collecting may be traced back to the late 19th century when Singapore was developing rapidly as a vibrant British colonial port city. By then, Chinese migrants had formed the majority of the local population. As local Chinese businessmen became more affluent, they had the means to buy artworks, either to support artists, or as a means of cultural identification.

The most prominent example was the famous scholar and poet Khoo Seok Wan (1874-1941) who inherited a fortune from his father who was a rice merchant. With his wealth, Khoo set up schools and newspapers, founded cultural societies, and collected the works of calligraphers and painters. Hence, it is evident that wealthy or educated individuals like Khoo in 19th century Singapore continued the Chinese literati tradition of exchanging artworks as gifts, and inviting friends to write poetry on special occasions.

Some local collectors like Huang Manshi even went on to develop deep friendships with artists such as Xu Beihong, whom they encouraged and supported financially over the years.

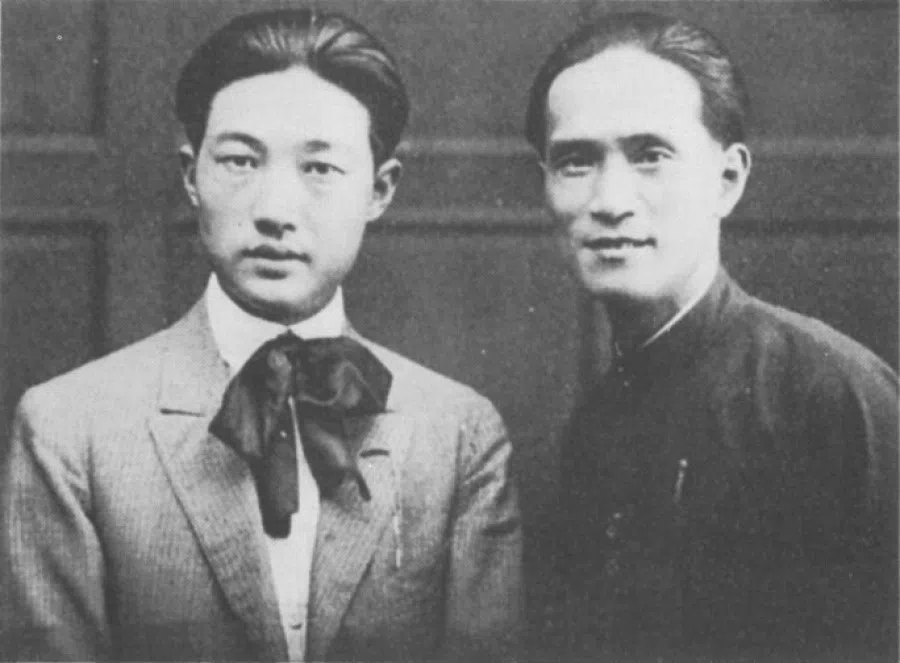

This became more pronounced in the early 20th century when the political and social instability in China led more artists such as Xu Beihong and Liu Haisu to travel to places like Singapore to exhibit and sell works to wealthy overseas Chinese. Apart from their own works, they sometimes brought antique paintings for sale as well. Some local collectors like Huang Manshi even went on to develop deep friendships with artists such as Xu Beihong, whom they encouraged and supported financially over the years.

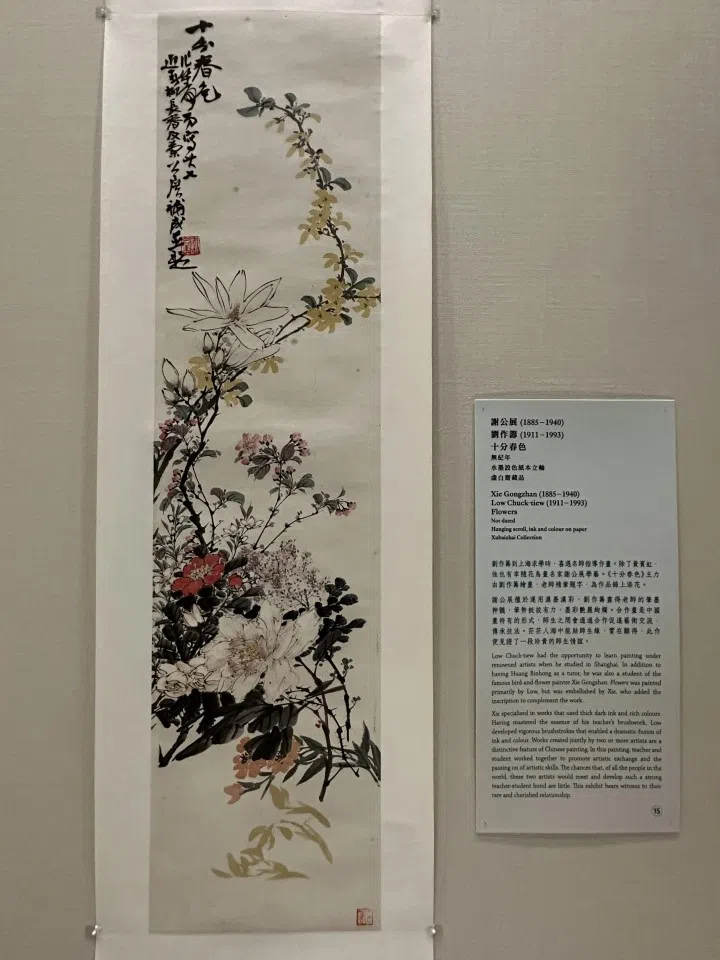

Apart from wealthy businessmen, early collections were also formed by local artists like Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Tan Keng Cheow who had been born and educated in China in the early 20th century. Hence, they had opportunities to know artists like Liu Haisu and Huang Binhong who were their former colleagues, classmates or teachers in China. As a result of such ties, the mutual gifting of artworks was a common practice, and local artists eventually acquired significant collections of ink paintings from their overseas counterparts.

High-quality works from China became available for acquisition overseas since there was little demand for art and antiquities in China after the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949.

Peak in collecting

After the end of World War Two, art collecting in Singapore continued, but the sources of acquisition became more diverse. Due to geopolitical tensions, overseas travel for Chinese artists became more difficult, and local collectors could no longer buy easily from artists directly. Instead, businessmen-collectors like Tan Tsze Chor, Yeo Khee Lim and Low Chuck Tiew relied more on art dealers, galleries and auction houses in Singapore and Hong Kong.

High-quality works from China became available for acquisition overseas since there was little demand for art and antiquities in China after the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949. Consequently, local collectors were able to expand their collections rapidly during that period.

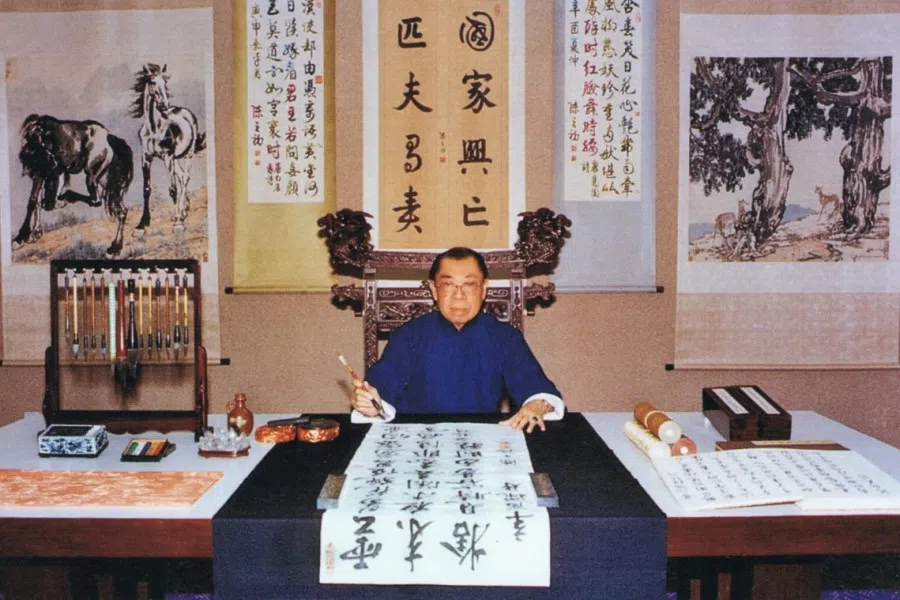

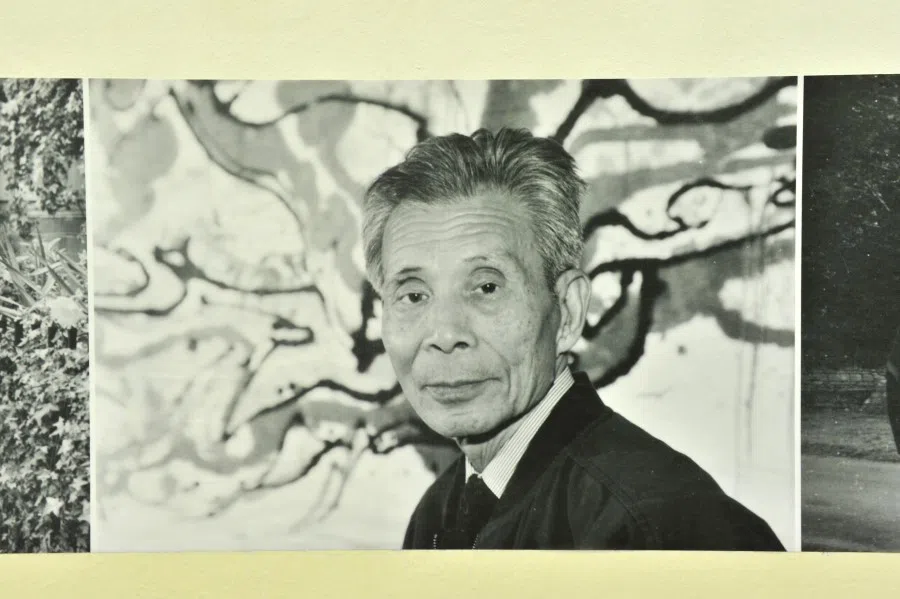

After the end of the Cultural Revolution and when China reopened to the rest of the world in the 1980s, Chinese artists became active again, and were eager and able to exhibit overseas. In Singapore, commercial galleries like Sin Hua Gallery and Orchard Gallery were set up, selling works sourced from China, and inviting Chinese artists like Liu Haisu, Xie Zhiliu, Cheng Shifa and Wu Guanzhong to Singapore for exhibitions.

Many local collectors were open to new trends in ink painting, likely due to their exposure to a more cosmopolitan lifestyle in Singapore. Hence, experimental Chinese artists found a ready audience in Singapore who appreciated their pioneering efforts.

That period coincided with Singapore becoming an industrialised economy with a growing middle class. It saw the rise of a pool of largely English-educated professionals, such as doctors and lawyers, who became interested in collecting ink paintings. Some of them went on to form a collector's society known as Forum of Fine Arts in 1991, the first formalised group of its kind in Singapore, catering mostly to English-educated collectors. This was a departure from the collectors active in the post-war period, who were mainly wealthy Chinese-educated businessmen.

The interest in collecting ink painting peaked in the 1990s, with local galleries organising frequent exhibitions, at the rate of almost one every fortnight. Many local collectors were open to new trends in ink painting, likely due to their exposure to a more cosmopolitan lifestyle in Singapore. Hence, experimental Chinese artists found a ready audience in Singapore who appreciated their pioneering efforts. This included Wu Guanzhong who was criticised in China for his artistic innovations in the 1980s, but whose works sold well in Singapore. (Based on interviews with Singapore Chinese painting collectors and artists in 2021.)

These early collectors have been replaced by younger individuals with more eclectic tastes, ranging from Southeast Asian modern art to global contemporary art.

Turning point

The collecting fervour slowed down in the early 2000s, largely due to the rise of China. With their growing affluence, the number of collectors grew in China. Stronger demand led to higher prices, and Chinese artists had fewer incentives to exhibit or sell in Singapore. Eventually, some local collectors found such paintings beyond their reach. At the same time, appreciating prices led some to divest and switch to collecting other types of more affordable artworks. The period also saw a generational shift in local collectors.

By the 2000s, many of the key collectors from the post-war period had faded from the scene. Some like Low Chuck Tiew chose to donate their collections overseas. The collections of Huang Manshi and Tan Tsze Chor were largely dispersed after their demise, with a small portion of the latter's collection being donated to the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. These early collectors have been replaced by younger individuals with more eclectic tastes, ranging from Southeast Asian modern art to global contemporary art.

Recent trends

However, ink painting remains of special interest to a number of local collectors. They include the Yeo brothers who have kept intact and expanded the collection started by their late father Yeo Khee Lim. In recent years, the collections of modern and contemporary ink paintings put together by individuals like Whang Shang Ying and Chan Kok Hua have become more prominent. The former focuses on modern and contemporary ink paintings by artists in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the larger overseas Chinese community. The latter started with collecting works from 19th and 20th century Chinese artists, and has recently expanded his ambit to include works by Singaporean artists.

This is likely to be the future direction for the art scene in Singapore, as more local collectors take on a more transnational, or globalised, approach in their collecting of ink paintings.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)