Vietnam is balancing China-US rivalry with deft statecraft, but for how long?

In Southeast Asia, Vietnam accompanies a unique position when it comes to navigating the tricky shoals of ensuing Sino-American rivalry. Apart from the Philippines, Hanoi sits on the front line of territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea.

In its contest with China for power and influence, Washington has also identified Vietnam (and Singapore) as key Southeast Asian states in its so-called free and open Indo-Pacific strategy.

This is why Vietnam's statecraft is critical. This refers to a sophisticated application of diplomacy, with mixed strategies utilised to secure Vietnam's national interests and maintain its relationships with the US and China, yet maximising its foreign policy flexibility. The application of statecraft is important, given that Vietnam is in a bidding war between China and the US, and the two major powers are trying to incline Vietnam towards their side in the ensuing geopolitical rivalry.

In March 2021, the Biden administration's Interim National Security Guidance document mentioned Vietnam and Singapore, together with 'other ASEAN member states' (in addition to New Zealand and India), as countries that could partner with the US in the implementation of its Indo-Pacific strategy.

Washington's strong commitment towards forging cooperation with Vietnam was also underscored by US Vice President Kamala Harris's three-day visit to Hanoi in August. America views Vietnam as a trustworthy partner accelerating its engagement with Southeast Asia, given Hanoi's geostrategic importance and its emerging regional role.

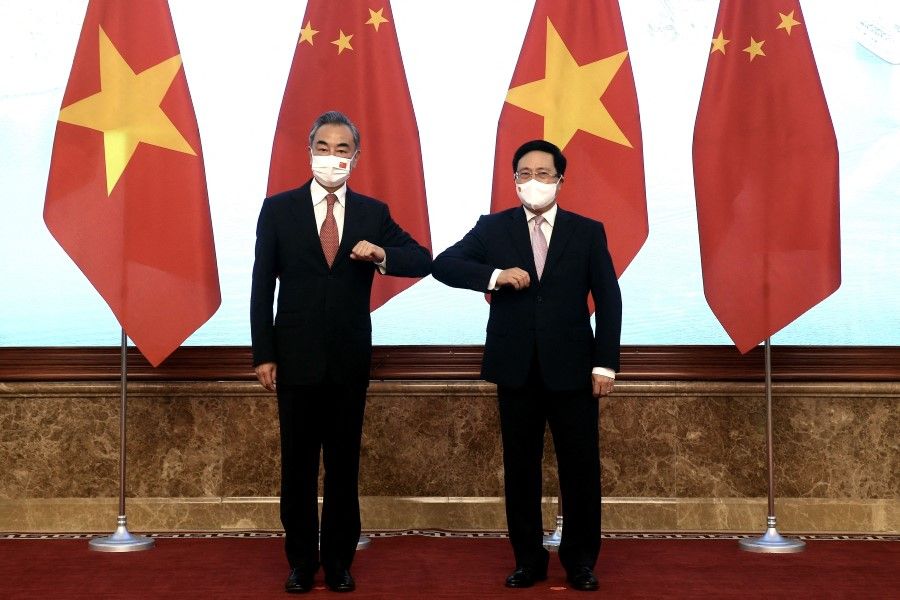

Cognisant of this, China sought to preempt the US Vice President's visit. With a shipment of 200,000 Covid-19 vaccines to Vietnam right before Harris's visit, China sought to outplay the US on vaccine diplomacy and maintain traction in Sino-Vietnam relations.

The nationalistic Global Times even reminded Vietnam of its geographical proximity and ideological affinity with China and called for Vietnam's 'wisdom' against 'superficial closeness' with America. In effect, China, in playing its Communist comradeship card with Vietnam, attempted to curb Hanoi's freedom of diplomatic manoeuvre.

On its part, Vietnam deftly offered an olive branch to China by saying the delivery was timely. It also reiterated its oft-used "four-nos" policy - no military alliances, no alignment with one country against another, no hosting of foreign military bases, and no using of force or threatening to use force - to placate Chinese concerns about Hanoi becoming more inclined to the US.

It was quite astute of Hanoi: in welcoming the Chinese ambassador's delivery of the vaccines, Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh was careful not to mention the country's pursuit of independence and multilateralism in the form of seeking deeper ties with the US.

In the past, China underscored ideological commonalities between Vietnam and China, two socialist states which have adopted a degree of openness and free-market elements in their economies.

In 1991, ideological similarities played a crucial role in the normalisation of Sino-Vietnam relations. The communist parties of the two countries sought to push back at the triumphalism of liberal democratic ideals after the end of the Cold War. Vietnamese political leaders attempted to solidify the red position with China on ideological grounds after the 8th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam in 1996.

Conversely, there are clear ideological dissimilarities in the US-Vietnam relationship. But the ideological factor in Vietnam's relations with China and the US may not matter as much.

Arguably, the independent variable that frames Vietnam's statecraft of navigating the tripartite relationship is its national interest - security, independence and survival.

Vietnam and China's respective stances on foreign policy have diverged considerably. China's Belt and Belt Initiative reflects its desire for a Beijing-centric world system. But Hanoi strives towards multilateralism and has sought to reduce its economic dependence on Beijing; it seeks to uphold existing international law and norms against the latter.

According to one Vietnamese analyst, the two communist parties have maintained a range of dialogues, but ideology mattered less and less in the foreign affairs of Vietnam and China and in their relations, as it could not halt China's regional ambition, which entails getting embroiled in territorial disputes with Hanoi in the South China Sea.

Over time, ideology has given way to pragmatism as Hanoi has pursued better ties with socialist states and free-market democracies (like the US) alike. Arguably, the independent variable that frames Vietnam's statecraft of navigating the tripartite relationship is its national interest - security, independence and survival.

Essentially, the US and Vietnam are heading into new territory even when the relationship is still technically a comprehensive partnership. In July and August, respectively, US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin's and Vice President Harris's reaching out to Hanoi facilitated bilateral cooperation on maritime security, Washington's vaccines offerings to Vietnam, and the establishment of a Centers for Disease Control office in Hanoi. The US outreach is indicative of a more broad-based approach to Vietnam, rather than one focused only on traditional security.

In its pursuit of Vietnam, Washington has also sought to downplay any dissimilarities in the two countries' political systems. With its assurance of engagement to support Vietnam's independence and sovereignty, Washington is also testing Vietnam's willingness to upgrade its ties to a strategic partnership. Whether this actually happens is a matter of Vietnam's statecraft. This involves balancing the competing demands of Beijing's concerns about enhanced US-Vietnam relations against the need to maintain Vietnam's independence and security by forging closer ties with the US.

On paper, it would be risky for Hanoi to develop a deeper relationship with Washington as this would antagonise its giant neighbour. Yet, the question here is how much risk Vietnam is willing to take: China has shown no qualms about intimidating Vietnam, notably in the South China Sea.

Put differently, Hanoi is acutely aware of Chinese concerns as it considers an upgrading of ties with the US, even as Washington continues to foster its ties with Hanoi while keeping up its integrated deterrence to deter China's military activities.

But China has to be mindful here: Beijing's continued opposition to better Vietnam-US ties could backfire, such that Vietnam's adopting of a strategic partnership with the US could happen sooner than anticipated.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.