When the only option is fraud: How institutional faults led to the spread of the coronavirus in Wuhan

Chen Kang attributes the blindspots in China's handling of the Covid-19 outbreak to the tendency of officials to withhold information and put up appearances for their own interests. As such, decision-making could be impaired by the asymmetry of information and misaligned interests between superiors and subordinates, especially at the local level. Results then vary based on how well one navigates the minefields of groupthink, collusion and that seemingly innocuous aim of not rocking the boat. Using the prism of formalism, or what is prizing form over substance, Chen points out the weakness of a centralised system.

Formalism in China is a style of work, in which great attention is paid to established formalities such as routine, proper procedure, etiquette and ceremony, with disregard to whether form and substance are in sync.

Formalism in this sense has evolved into a peculiar phenomenon in which officials "do their best to put on a show" (认认真真走过场、轰轰烈烈搞形式). They waste precious time on endless paperwork and meetings. They fill up forms, prepare materials, and accumulate photo and video evidence. They subject themselves to all manner of inspection and go through typical inspection routines repeatedly.

Ironically, even though people complain about formalism, they grow accustomed to it eventually. In fact, it seems unavoidable and requires both superiors and subordinates to play along. Simply put, it is an outcome chosen by the entire bureaucracy; it is a type of collective action.

At times, protests against formalism surge and there have been many anti-formalism movements in recent years. However, these often peter out or descend into a formalism of its own. Why is formalism problematic? What causes it in the first place? We can get a clearer picture by examining it through the lens of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The party with more information reaps greater benefits

But first, it is important to understand the economic theories underpinning formalism. In China, there is a saying that "from Nanjing to Beijing, sellers outsmart buyers". Sellers have the upper hand because they know the quality, functions and cost of their goods. To protect their business interests, sellers will not share all they know with buyers. Instead, they take advantage of this information asymmetry to generate more profits.

Information asymmetry does not only exist between buyers and sellers. It is also found between shareholders and managers in business organisations, and between superiors and subordinates in government institutions. Information asymmetry allows the party with the upper hand to reap greater benefits.

Adverse selection as seen in subpar used cars and medical insurance

One type of behaviour regarding taking advantage of information asymmetry takes place before a contract is sealed or the relationship among vested parties formalised. This is known as adverse selection. Those who are most eager to close the deal often come with the most risks. The harder it is to distinguish accurate information, the easier it is to pass off the fake as genuine, and the more grievous the adverse selection.

George A. Akerlof, a Nobel laureate in economics who wrote the 1970 paper "The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism", was the first to explain the behaviours involved in adverse selection using an analogy of the used cars market. His research found that buyers were generally unable to differentiate cars that were well-maintained from those that were problematic (lemons). At the same time, buyers were only willing to pay lower prices, leading sellers that had cars in good condition to refrain from selling. Therefore, these sellers exited the market and most of the used cars left were subpar. Thus, information asymmetry led to adverse selection in the used cars market.

The medical insurance market is also afflicted by adverse selection. Healthy individuals feel that they do not require insurance while those who actively seek coverage tend to be the ones who are more likely to make claims. This leads to higher costs for insurers and consequently higher premiums. As a result, a greater number of healthy policyholders would withdraw from their insurance plans and further increase the costs for the insurance companies. In this example, adverse selection leads to the atrophy of the private medical insurance market.

When capable subordinates are overlooked

Adverse selection is also an issue when choosing government cadres. Consider a scenario where leaders are keen to promote cadres who are loyal and capable, with priority given to loyalty. Information on a candidate's loyalty or ability is not readily available. It is difficult to tell whether a candidate is truly capable until he or she has taken up a key leadership position or has faced a real challenge. Under such circumstances, how would candidates or those looking to be groomed try to improve their chances? They would signal their loyalty by completing assigned tasks as quickly as possible, or as best as they can. In addition, they would avoid reporting problems so as not to trouble their superiors.

For example, they would do their best not to let bad news about the Covid-19 epidemic mar the mood of the Spring Festival. More importantly, they would avoid contradicting their superiors or trying to outshine them. Those who are more meticulous will even come up with unique ways to show respect to their higher-ups, thereby leaving favourable impressions. Those especially eager to prove their loyalty would even seize every opportunity to pledge their loyalty and compliment their superiors.

Faced with these complex signals, higher-ups who enjoy such declarations of loyalty may well end up promoting two-faced subordinates who are adept at feigning loyalty but lacking in ability. This would encourage more subordinates to take similar approaches. At the same time, those truly capable may be overlooked because they do not demonstrate their loyalty regularly.

Moral hazard and unethical behaviour for personal gain

Moral hazard is another type of behaviour that takes advantage of information asymmetry. It occurs after a contract is sealed or the relationship amongst vested parties formalised. In a moral hazard, one party to the contract engages in behaviour that is unethical or which exposes the other party to higher risks because it does not have to bear the consequences.

There are quite a few real-life examples. For instance, insurance companies have to deal with cases of customers who set their houses on fire after obtaining coverage. Another example is that of state-owned enterprises. Prior to the establishment of an effective bankruptcy mechanism, the managements of these companies were lackadaisical in running them since the state would absorb any loss. Such problems between the principal and its agent is a type of moral hazard.

While a ruler's interest is to reward those who have made contributions, a subject's interest is to be rewarded even without making contributions.

The principal-agent problem is also known as the agency problem. An example of a principal-agent relationship is that between a company's shareholders and its general manager. Shareholders are the principals who appoint the general manager to run the company on their behalf. Similarly, superiors and their subordinates in the public sector are also in principal-agent relationships. As principals, superiors delegate some authority to their subordinates; as agents, subordinates exercise powers and bear responsibilities on behalf of their superiors.

The agency problem arises due to information asymmetry in a principal-agent relationship. Typically, the principal only sees the outcome without being able to directly observe what the agent has done to achieve it. Since the interests of agent and principal are not the same, the agent may be motivated to go against the principal's interests for personal gain. In other words, the agency problem refers to the moral hazard that principals face.

Misaligned interests of superiors and subordinates

Han Feizi, a Chinese philosopher from the Warring States period, was acutely aware of an agent and a principal having different interests. In Gufen (《孤愤》, lit. solitary indignation), he wrote that rulers have different interests from their subjects: whereas it is in a ruler's interest to appoint those who are capable as officials, a subject's interest is to obtain such an appointment even without any real ability; while a ruler's interest is to reward those who have made contributions, a subject's interest is to be rewarded even without making contributions; and though a ruler's interest lies in having a multitude of talents for various purposes, a subject's interest lies in colluding with like-minded others for personal gains. Such inclinations of the subject (assuming the worst in human behaviour) creates a moral hazard problem for the ruler. More than two millennia later, the interests of principals and agents are still misaligned.

Agents are able to harm the interests of their principals for personal gain because they have an information advantage. Naturally, principals would try to reduce moral hazard by mitigating the information asymmetry. Loathing to lose the advantage, agents would duel with their principals over crucial information that concerns their interests.

Subordinates cannot refuse their superiors' demands for information. Thus they resort to deception. Such deceptive ruses have even inspired a few Chinese ditties.* The repeated game of information and disinformation played between superiors and subordinates has ultimately produced formalism as a by-product.

... Xuexi Qiangguo (学习强国, lit. learning nation) app was rolled out in 2019 to monitor the progress of party members and cadres... In the end, users were only interested in accumulating points without doing any actual learning.

Superiors request for information directly from subordinates by having them fill up forms or submit materials and data. To prevent superiors from knowing the actual situation, subordinates fabricate or manipulate data to suit what the superiors are asking for, creating fake model examples or classic cases. Aware of such practices, superiors know they have to markedly trim down these inflated data.

Advances in information technology have made superiors seemingly all-seeing and all-hearing. They now have more diverse and timely ways of requesting information from subordinates. A common practice in recent years is to set up WeChat groups for subordinates to report progress accompanied by photo and video evidence. But this does not mean that superiors are getting more accurate information. Subordinates struggle to cope in many cases since most of their time is taken up by commuting, taking photos and putting on a show. Actually, photographs may not show the true picture since those who do not have time may resort to taking the photos beforehand or after.

In another example, the Xuexi Qiangguo (学习强国, lit. learning nation) app was rolled out in 2019 to monitor the progress of party members and cadres with regards to political learning. Users were assigned learning tasks to be completed within a certain period, with points and rankings used as motivation. In the end, users were only interested in accumulating points without doing any actual learning. For example, they attended to other matters while a video in the app was playing on their learning devices. Some even used software that can hack the app to help them earn points.

Unwieldy reporting systems during Covid-19

The Covid-19 epidemic provides another case study. After the SARS outbreak in 2003, the central government and local governments in China jointly invested some 700 million RMB to build an infectious disease direct reporting system so that the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and national health authorities could be informed of an infectious disease outbreak in any part of the country within 24 hours.

The higher an individual's position in a bureaucracy pyramid, the greater the number of subordinates colluding against him or her.

However, the Covid-19 epidemic showed that these best-laid plans failed. The purpose of the system is to allow doctors at the frontline to file reports directly. However, the reality is the doctors had to report up their chain of command (all the way to the provincial-level health commission) to obtain approval first. So, the CDC was only informed through the reporting system after more than a hundred Covid-19 cases were logged in Wuhan. Establishing the direct reporting system did not fundamentally change how information propagated. This is proof that progress in technology alone is insufficient for superiors to overcome their information disadvantage. Instead, it can lead to new types of formalism.

Collusion among local governments muddies the waters

Other than requesting information from subordinates, superiors can also send inspectors or go down to the ground personally to find out how things are. Whenever this occurs, all subordinate units would team up to deal with their superiors so that critical information detrimental to their assessment is not divulged. For example, city, county and township officials would join hands to handle inspectors sent by the provincial government. When a city-level government sends inspectors, county and township-level officials would team up to handle them. Somehow or other, those to be inspected are able to find out details of the inspection, such as the time and date, location and even vehicle plate numbers of the inspectors, and prepare beforehand.

Professor Zhou Xueguang of Stanford University terms this "collusion among local governments". The higher an individual's position in a bureaucracy pyramid, the greater the number of subordinates colluding against him or her. A person at the apex of the pyramid would have to contend with everyone else colluding against him or her.

Disclosing information without the approval of a direct superior is immature and out of line, and the individual will not be trusted in future.

What leads to such collusion? In theory, power to govern is given by the people. As the principal, the people delegate the managing of the country to the government. In a unitary state, the central government delegates some of its power to provincial governments, which in turn delegates some of its power to its subordinate governments, and so on, resulting in a long chain of principal-agent relationships. While the central government does the overall planning, the lowest level of government executes after the instructions have been passed through several intermediate layers. In such a multilevel governance structure, a leader at each level is concurrently a principal and an agent.

For example, a city-level leader is the principal of county-level leaders, and an agent of the provincial leader. When inspecting counties, the city-level leader hopes to see the real picture to reduce the information asymmetry with his or her subordinates. However, when it is his or her turn to be examined, he or she would want to preserve the information advantage by withholding critical information that can affect his or her interests. At this point, his or her interests are aligned with those of his or her subordinates because they are now all agents and their fates are intertwined.

Is it possible then that a county-level leader steps out of line and leaks information that the city-level leader wishes to withhold from the provincial leader? It is unlikely because such meetings are usually scripted, right down to who gets to attend and speak, and what is said. Disclosing information without the approval of a direct superior is immature and out of line, and the individual will not be trusted in future. More importantly, city-level leaders have direct oversight over county leaders and have the power to nominate them for their next position. An individual who is not nominated has no chance of being groomed and suffers a severe setback to his or her career development. Nomination rights ensure that county-level leaders are on the same side as city-level leaders in this tug-of-war over information.

However, both sides are willing to compromise and neither calls the other's bluff so that what needs to be done gets done and all involved appear to have done their part.

Such collusion renders inspections and the like nothing more than mere formalities since inspectors and their targets know what to expect. After all, putting on a show is much easier than getting actual work done. Having been on the receiving end, inspectors would have experience of colluding with others to survive inspections and thus would know what to expect.

If superiors make decisions without considering the actual circumstances so that implementation is impossible, subordinates have no choice but to resort to fraud.

On the other hand, subjects are also aware that the inspectors are experienced enough to realise they are ganging up to pass the inspection. However, both sides are willing to compromise and neither calls the other's bluff so that what needs to be done gets done and all involved appear to have done their part. The national team of medical experts sent to Wuhan in the early days of the epidemic may not have been familiar with such ways, so it is no wonder they were misled to conclude that "the situation is under control" then.

In short, the information asymmetry between principals and agents, and their misaligned interests are the cause of agency problems. The bigger the difference in interests between superiors and subordinates, the likelier it is to result in formalism. Superiors that impose policies across the board leave their subordinates with little flexibility in the execution. This leads to lax governance and officials no longer strive to come up with appropriate implementation details for the region or department. They become passive and end up passing on instructions from their higher-ups mechanically without doing any actual work. If superiors include quantitative indicators in performance reviews, subordinates would play number games by tallying "alternative targets" such as the number of meetings organised and number of participants. If superiors make decisions without considering the actual circumstances so that implementation is impossible, subordinates have no choice but to resort to fraud.

Of course, there are also types of formalism that have nothing to do with information asymmetry and misaligned interests. For example, meetings that do not focus on actual issues or problems. Having a big meeting over a small matter and vice versa, while meetings are not called for key issues, this is another problem altogether.

Consequences of formalism far-reaching

On the surface, formalism may seem silly and harmless, but its consequences are far-reaching. The people suffer the most harm to their interest when officials cover up for each other, sweep things under the carpet, commit fraud and gloss over problems.

Data from the World Trade Organisation shows that during the period of 1950 to 1993, China's annual exports as a fraction of the global total was the highest in 1959, a peak which was not surpassed until 1994, 15 years after China's reform and opening up.

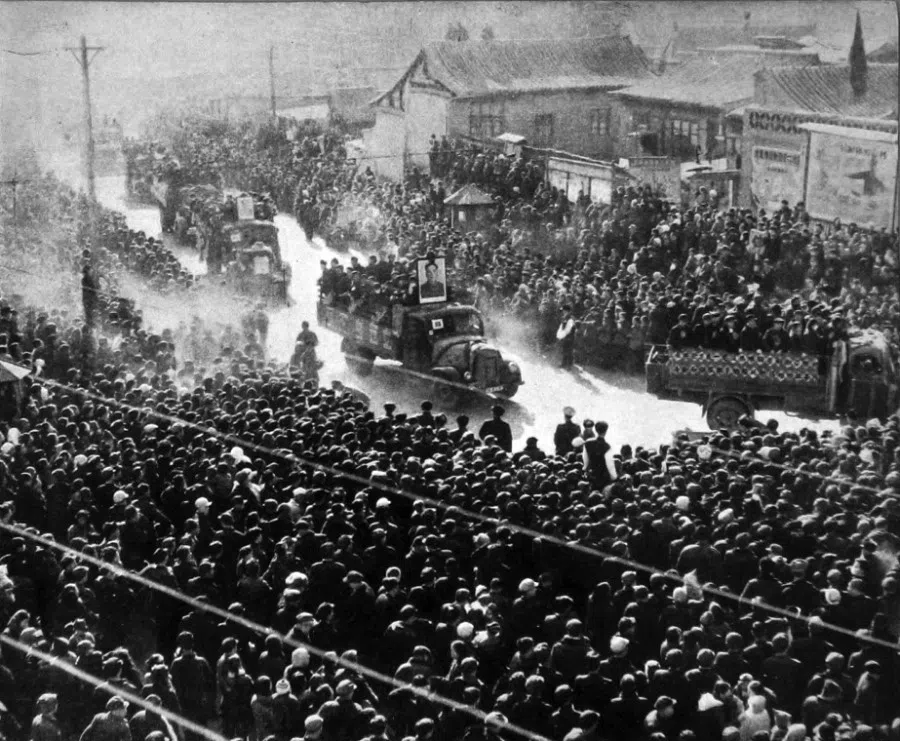

Perhaps in a similar vein, during the early days of the Covid-19 epidemic, the local authorities in Hubei and Wuhan deliberately withheld information about human-to-human transmission, resulting in precious time lost and disastrous consequences subsequently.

In 1959, China exported an unusually large amount of agricultural goods, especially grains. It was the year in which the Great Leap Forward campaign was at its height. The impulsive central government set impossible targets for grain production. Left with no choice, local governments withheld the actual situation from their higher-ups by exaggerating grain production figures and lying blatantly that there was more grain than the people could consume. Since there was a surplus of grain, the central government decided to export it in exchange for foreign currency. It was only discovered later that the actual amount of grain produced in 1959 was 25 million tonnes fewer than in 1957, yet 4.2 million tonnes of grain was exported in 1959, double that in 1957.

Not only that, they are not monitored by the common people who hold accurate basic information.

So, where did all that grain come from? When the central government requisitioned grain, local governments expropriated farmers' rations to cover up their lies, causing a catastrophic famine.

Perhaps in a similar vein, during the early days of the Covid-19 epidemic, the local authorities in Hubei and Wuhan deliberately withheld information about human-to-human transmission, resulting in precious time lost and disastrous consequences subsequently.

In conclusion, formalism is essentially a principal-agent problem. On one hand, those at the apex of principal-agent chains are only principals nominally since they are unable to hold their agents accountable. On the other hand, local governments at the base of such chains collude with their immediate superiors. Not only that, they are not monitored by the common people who hold accurate basic information. Hence, the key to eradicating formalism is to address institutional issues so that principals play more than just nominal roles and local governments are held accountable by the people they serve. Instead of solving problems, getting subordinates to signal their loyalty only leads to adverse selection and aggravates the divergence of interests.

Note:

*Deceptive ruses that subordinates resorted to in order to get around their superiors' demands for information inspired this Chinese ditty:

村骗乡,乡骗县,一直骗到国务院。

国务院,发文件,一层一层往下念,

念完文件进饭店,文件根本不兑现。

Village to town, county to State Council, lies run through from bottom up. Then comes a message from top down, layer by layer it's passed down. Let's all drink a round, the message becomes null.