Why China will continue to experience power cuts

In September 2021, a number of electric power outages in Chinese provinces attracted the attention of Chinese social media websites, official government websites and foreign news media. Such power outages used to be quite frequent in many locations in China, but they have become quite rare during the last decade. Therefore, the scale of outages, including scheduled power cuts for selected industries and some unanticipated electric power interruptions in residential areas, caught observers by surprise.

The reasons for these outages are complex, involving a range of factors including the effects of bad weather, coal price inflation, unavailable supply of coal or renewable energy, rapid growth of production due to export orders, electricity generation and transmission problems, and climate change-related policies. In addition to briefly discussing these immediate factors creating the outages below, it is worthwhile to raise the perspective to a bird's eye view in order to understand the structure of energy supply and demand in China, and the long-term effects of policies that influence the electric power sector.

A jump in demand and cost for coal

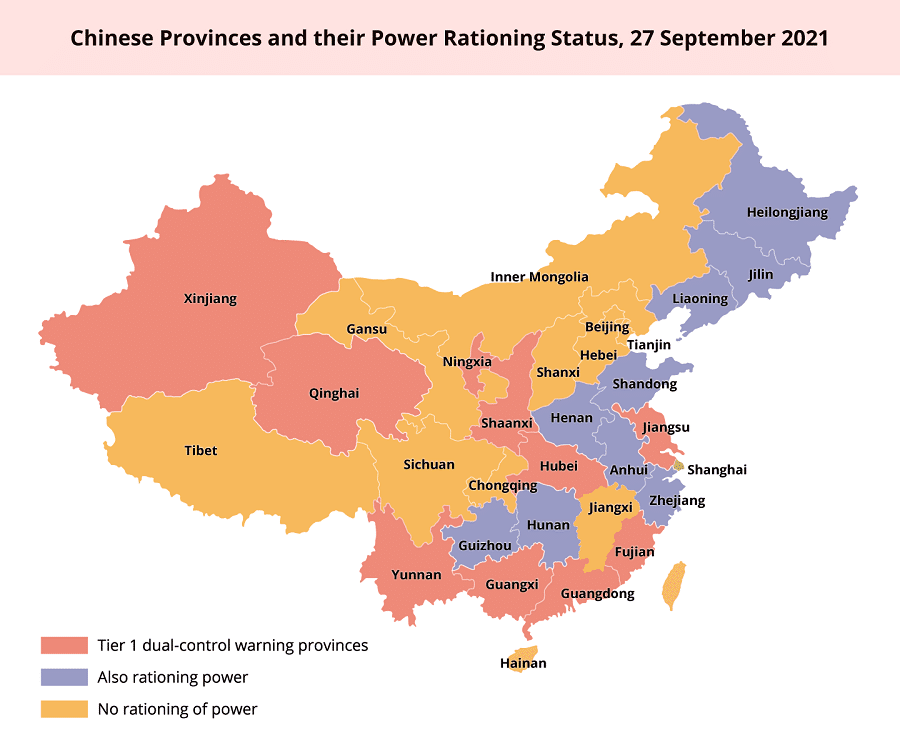

The electric power interruptions in China in September 2021 affected more than 20 provinces, but hit especially hard at some of the advanced manufacturing powerhouses in provinces such as Jiangsu and Guangdong, together with the industrial centres of the Northeast. Much of this was scheduled power shedding - "orderly electricity consumption" in the official language of the government - that curtailed power supply for energy-intensive production during a period of one or several days.

Goldman Sachs has reportedly reduced China's economic growth forecast for 2021, due to energy shortages and deep industrial output cuts, to 7.8% from the previous estimate of 8.2%. These power cuts were partly due to the "dual control" national policy to reduce carbon emissions that put limits on overall energy consumption and sought to reduce energy intensity. In August, the National Reform and Development Commission (NDRC) announced warnings of dual control restrictions for ten Tier-1 provinces that failed to meet energy consumption and intensity targets in the first half of the year.

China's total power consumption increased 13.8% over January-August, while power generation only managed to increase 11.3% over the same period.

However, in Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang and Beijing, the power outages also affected residential areas. In some cities, unscheduled power cut incidents were causing social media reactions, as people were caught in lifts, traffic lights were shut down, or ventilators stopped so that people had to be committed to hospitals due to poisoning by carbon monoxide.

In response to these events, the NDRC on 30 September issued instructions to the authorities to "make the public's basic power needs the top priority of its power-supply work, ensuring that households stay safe and warm throughout this winter."

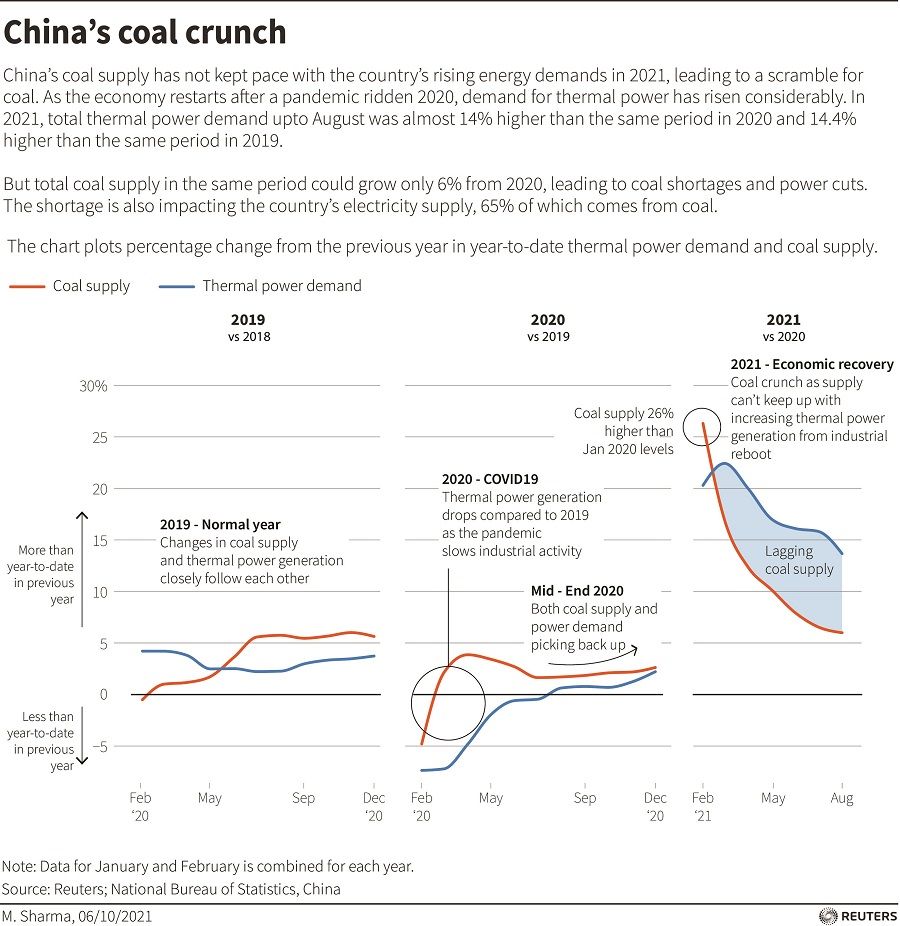

One factor that influenced the power outages was the increased demand for electricity. Industrial demand for electricity grew rapidly as Chinese enterprises geared up to supply local and global markets during the economic rebound from Covid lockdowns. Moreover, residential demand in some provinces grew due to air-conditioning requirements during heatwaves.

China's total power consumption increased 13.8% over January-August, while power generation only managed to increase 11.3% over the same period. This pushed peak demand up, with the result that the electricity utilities were forced to shed power in order to maintain the safety of the grid.

While demand for power increased, the supply was constrained by power generators lacking fuel resources or unwilling to ramp up production due to the inflation of the price of coal. Even if China has succeeded in reducing its reliance on coal for electricity generation from 68% in 2015 to 61% in 2020, electric power generation in China is still heavily dependent on coal.

Unfortunately, thermal coal prices have increased 50% during the last three months, and are now 137% higher than a year ago. The inflated price for coal is related to several factors: first, production at coal mines in China have been limited since government has made it illegal to exceed benchmark production capacity (that had been allowed earlier); second, imports of coal have also been affected by rising costs and supply restrictions, including a ban on imports of Australian coal introduced for political reasons in October 2020; third, imports of coal from Mongolia and Indonesia, designed to replace the Australian coal, have not been able to keep up with demand.

The rising cost of fuel is combined with a fixed price for the generation of coal-based electricity for consumers, often making the supply of electricity to the grid a loss-making activity for power utilities in China. This has become one of the most serious issues for power generator units that naturally are reluctant to cut into their limited stores of coal, only to lose money generating electricity for the grid.

The retail prices for supplying a kilowatt-hour (kWh) to the electricity grid are fixed, being regulated by the government and approved by the NDRC. For household residents, the price of 1 kWh is around 0.5 RMB, which is low by international standards. That price is cross-subsidised by slightly higher prices charged to industries and services, but the electric power grid operators are not at liberty to charge consumers on the basis of the cost of production.

The big picture

The various factors summarised above coincided to land a number of actors in a situation where shedding of electric power in some locations was the only option available. However, even if the September blackouts were unusual for the season and particularly widespread in China, the phenomenon of power interruptions is still frequently experienced by major customers - although not to the extent to which blackouts were common in the 1980s.

The problems should be seen in a wider perspective, connected to the structure of energy supply and consumption on the one hand, and related to policy decisions regarding such issues as investments in infrastructure, mitigation of climate change, and the market forces in provision of services on the other hand.

Electricity supply

It is one of the great ironies of energy supply in China that many coal-fired plants run at 50% capacity or lower, while local governments continue to approve construction of new power plants. In other words, China has the installed capacity to more than supply peak power demand, provided that fuel is available and the electric grid is functioning in an optimal manner.

However, overinvestment in power plants is driven by the incentives for party cadres to get larger boosts to gross domestic product (GDP), employment and revenue from building their own power plants rather than importing power from other provinces, and the tendency to build power plants near heavy consumers of energy. So, new power plants are approved by local governments despite the priorities of the central government to cut emissions of CO2.

In addition, the central government has been limiting the production or imports of coal due to considerations of safety, pollution, climate change mitigation or foreign affairs; therefore, the availability of coal for power generation (which is only one of the user groups for coal) is often constrained. Adding to this the fact that transport of coal in China relies heavily on the railways, which are also frequently subject to delays and congestion, it is little wonder that the cost of coal is skyrocketing.

...the supply of electricity is plagued by structural constraints and conflicts between different actors, and the transition to new energy sources - away from reliance on coal - has been held back by short-term demands and the difficulties of integrating renewable sources.

The Chinese leadership has decided to expand low-carbon sources of electricity such as nuclear power and renewable power from wind, solar or bioenergy sources. However, despite the rapid construction of these types of electricity plants, their contribution to the electricity grid has not kept up with growing demand.

For one thing, renewable energy from wind and solar are still suffering from curtailment - that is, their supply of electricity is not well integrated in the grid - although the percentage of curtailment of photovoltaic power has declined from 11% in 2025 to 3% in 2020.

They are also often generating electricity in places remote from the site of consumption and thus depend on long distance transmission, for instance, via ultra-high voltage power transmission lines that have been gradually extended in China in recent years. These lines can supply around 4% of national electricity demand, but have been beset with tension between central government, state grid companies and provincial authorities.

To sum up, the supply of electricity is plagued by structural constraints and conflicts between different actors, and the transition to new energy sources - away from reliance on coal - has been held back by short-term demands and the difficulties of integrating renewable sources.

Electricity consumption

The problems faced in supply would not be so severe if China's government were able to fully implement its ambitions of reforming the patterns of electricity consumption away from perpetual growth towards higher efficiency. The high demand for electricity during 2021 is clearly related to the expansion of industrial production, much of it happening on account of new exports to the world market in a post-pandemic economic resurgence.

In the past, Chinese provincial governments often emphasised the development of heavy industries dependent on large energy supply such as iron and steel industries, cement or aluminium production, etc. as a corollary of rapid economic growth since the 1990s. Industry still consumes more than 50% of the electricity produced.

In the current period of the transition to a service economy and a slowing down of building and infrastructure construction, the government has wished to transform these high energy consumption industries with more energy-efficient technology.

During the 12th and 13th Five-Year Plans, provinces were asked to achieve energy-efficiency goals of 20%, which some were able to outdo, while others failed. Those successes were largely due to measures that represented "low-hanging fruit" (such as closing inefficient plants, or cutting power supply at regular intervals) and while the 14th Five-Year Plan for 2021-05 continues the campaign for energy efficiency, it also emphasises the strengthening of national energy security.

The current periodical power cuts due to the dual control instructions have targeted high energy-consuming industries, and were based on the NDRC's evaluation of the performance of individual provinces in meeting energy-efficiency goals and in reducing carbon emissions.

However, the Chinese economy is being electrified, that is, becoming increasingly dependent on the supply of electricity for economic activities, helped along by the rapid growth of the digital economy and reliance on electricity for most facilities in a household - such as air-conditioners, lifts, water supply, television and mobile phones.

Some of the core industries in this transition are themselves heavily dependent on energy, such as in the production of semiconductor components. Thus, it is likely that China's economic growth will still rely on energy supplies, but the country ought to be able to follow the path of advanced industrialised countries in Europe, which have managed to decouple GDP growth from greenhouse gas emissions.

Much of the power to implement policies has also been delegated to provincial or municipal levels, where priorities for energy efficiency investments, decommissioning of inefficient plants, and integration of renewable energy tend to get diluted by local priorities for GDP growth, employment etc.

Regulation, prices and subsidies

The Chinese leadership has pursued laudable policy aims regarding the expansion and integration of low-carbon sources of energy, commanding industries to raise energy-efficient production, investing in advanced electricity networks, etc. However, the implementation of such policies has been challenged by legacy regulation and a difficult transition to effective markets for energy.

The energy sector reforms of the early 2000s created a mix of actors, including three large regional grid corporations operating transmission and supply of electricity, a group of "big five" independent power generating corporations, and a host of local power utilities in the provinces.

To some extent, these actors are powerful enough to directly or indirectly defy detailed regulation by the NDRC and its subsidiary National Energy Administration, partly because there is a weak system for monitoring, verification and reporting that has occasionally produced inaccurate data.

Much of the power to implement policies has also been delegated to provincial or municipal levels, where priorities for energy efficiency investments, decommissioning of inefficient plants, and integration of renewable energy tend to get diluted by local priorities for GDP growth, employment etc.

Here we have to return to the issue of prices, in particular, the gap between the price of coal and the price which utilities could charge for the supply of electricity which has been a major reason for recent power outages.

The price of coal had been tightly regulated at a low level ever since the establishment of the PRC until 2006 when the NDRC finally allowed prices of steam coal for utility use to be fully subject to the market. But retail electricity prices remain tightly regulated by the central government to control inflation. Chinese utilities have thus been frustrated in their attempts to pass the increased costs of coal input to consumers. Accordingly, they resist pressure to generate electricity that will only serve to incur losses and the risk of bankruptcy (if they were allowed to go bankrupt in China).

This is the reason that recent news has reported that major utilities have petitioned municipal governments or the NDRC to allow them to raise the price for electricity supplied to consumers on the basis of the rising input costs. Other reports have indicated that NDRC officials have been receptive and have discharged teams from the National Energy Administration on fact-finding missions to utilities and grid corporations.

But the legacy of tightly regulated consumer price of electricity is still dominating policy thinking, not least because the authorities foresee social unrest if both residential and industrial consumers had to pay a price that really reflected costs.

Climate change

This brings us to the most pressing - but also the seemingly most remote - issue for energy consumption and production, namely, climate change policy priorities. President Xi Jinping has famously declared that China will peak emissions before 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060. This will depend to a large extent on whether China can phase out fossil fuel - and in particular, coal - in its energy system.

The NDRC dual control policy of cutting carbon emission and reducing energy intensity of production clearly serves this purpose. But a gradual release of the prices for electricity consumption would likely send strong signals through the system, reducing waste of energy throughout the country. Honest awareness of the deleterious effects of fossil fuel subsidies for sustainable development in China could add another element of incentives to replace fossil fuel with renewable sources of energy.

A subtle campaign?

On top of such considerations, one should recall that the national greenhouse gas emission trading system (ETS) that China has put into operation in July 2021 is intended to promote clean technology innovation in the electric power system.

The ETS will affect precisely the group of power generation utilities that are currently suffering a price scissor leading them towards bankruptcy; the ETS is designed to introduce a market for carbon emission allowances where the utilities is going to have to buy allowances for excess carbon emissions, beyond the free allowances that they are provided on the basis of benchmark production amounts. In the future, these carbon emission allowances will be auctioned away, if everything goes as the Chinese government expects (and similar to the ETS in Europe). No doubt this will add a new type of expense to the energy producers.

One could speculate that the current epidemic of power blackouts in China may be related to the prospects of higher input costs, combined with the expenses of purchase of carbon emission allowances... Do we see a subtle campaign to gain the opportunity to raise prices for their distribution of electricity by powerful actors in the energy system?